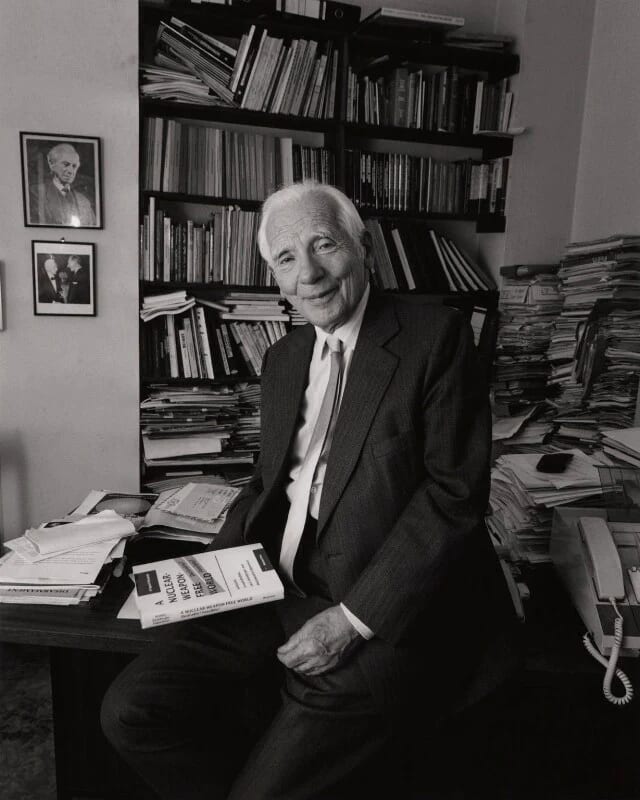

Remembering Joseph Rotblat (born on this day in 1908)

Joseph Rotblat was born in Warsaw on November 4, 1908.

He is one of the advisors I’d like to have on my shoulder, so on his birthday, I want to share a bit about his life and reflect on it.

As a brief overview, Rotblat:

Was the only scientist to leave the Manhattan Project on moral grounds

Founded and led the Pugwash Conferences, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995

Was the youngest of the 11 signatories of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto

Spent decades advocating for peace and nuclear disarmament

(I’m provisionally viewing November 4th as “Rotblat Day”, but if someone wants to organize a different date and event, I’d probably be happy to join.)

As with a similar post I wrote about Benjamin Lay, I want to flag that I’m not an expert; these notes come from casual reading and thinking over the last couple of years, and about a day of “research”. The post was written quickly and may contain mistakes.

Rotblat’s life

Warsaw

Rotblat’s parents had financial troubles, and instead of studying at a gymnasium, he was taught by a local rabbi. Rotblat later attended a technical school, worked as an electrician for some years, finally managed to enroll in and graduate from the Free University of Poland, and got a doctorate in physics from the University of Warsaw.

In 1938, Rotblat became the assistant Director of the Atomic Physics Institute, working with his mentor from university, Ludwik Wertenstein.[1]

Liverpool (1939-1943): the idea of a nuclear bomb

In 1939, James Chadwick (discoverer of the neutron) invited Rotblat to join his particle accelerator project at the University of Liverpool. Rotblat decided to accept the invitation, as he was interested in building an accelerator in Poland. His salary would be very small, so Rotblat’s wife Tola would have to stay behind.

While still in Poland, Rotblat had realized that nuclear fission could theoretically be used to produce explosions of “unprecedented power.” He was uncomfortable with the idea and had decided to put it out of his mind (later recalling that the move to Liverpool and the need to adjust to a new environment and language were welcome distractions — excuses to avoid thinking about a topic he found “agonizing”). As he settled in his new job, however, he grew increasingly worried that the Germans might develop an atom bomb; he was starting to think that the best way to prevent its use might be for an opposing country to make one first and threaten to retaliate.[2]

When he visited Poland later that year, Rotblat decided to seek Wertenstein’s advice on what he should do with this idea. His mentor found no error in Rotblat’s physics, but refused to recommend a course of action to Rotblat, saying only that he himself would not work on this kind of project.

Rotblat soon returned to Liverpool. Chadwick had managed to get Rotblat a raise, and Tola was supposed to join her husband as soon as she recovered from an appendicitis surgery. Tragically, two days after Rotblat returned after his visit to Poland, Germany invaded Poland.[3] Within a few weeks Poland was overrun and she was trapped. (Despite efforts to get her out through Denmark, Belgium, and Italy, she never made it out, and was later murdered at the Belzec concentration camp.)

This ended Rotblat’s deliberations. In November of 1939, Rotblat approached Chadwick with a project proposal to study the feasibility of the atom bomb, and soon started working on it with a small team that would later become part of the British “Tube Alloys” program.

The Manhattan Project (1943-1944)

In late 1943, a top-level decision was reached to merge the British Tube Alloys with the Americans’ Manhattan Project, and in early 1944, at age 36, Rotblat found himself in Los Alamos.

This was a “wondrous strange place.” Rotblat had always struggled to get enough funding for his experiments; here, requested equipment would arrive within days. (Apparently Rotblat and some colleagues decided to test the system one day by ordering a barber’s chair. It arrived with “minimal delay.”[4]) It wasn’t just the funding. Victor Weisskopf later described the atmosphere in the following way:

It was a heroic period of our lives, full of the most exciting problems and achievements. We worked within an international community of the best and most productive scientists of the world, facing stupendous tasks fraught with many unknown ramifications. All of us widened our intellectual horizons in this stimulating company that included giants like Niels Bohr and Enrico Fermi.

But Rotblat wasn’t happy, in part because he hadn’t heard from his family. He had also started doubting whether the Germans could match the “limitless technical resources” and “collective intellect” of this project. Still, the possibility that they would find a shortcut and manage to develop the bomb first remained, and Rotblat kept working.

Son after Rotblat’s arrival in Los Alamos, however, General Groves (director of the Manhattan Project and a friend of the Chadwicks’, with whom Rotblat was staying), came over for dinner and mentioned that the real purpose of making the bomb was to subdue the Russians. Rotblat felt betrayed, and this seems to have been an important turning point.

Over the course of the next months, Rotblat’s concern grew. He regularly talked to Niels Bohr, who often came to Rotblat’s room to listen to the BBC on the radio in the mornings, and who shared with Rotblat his concerns of a nuclear arms race. (Robert Wilson later described how most of the younger scientists at Los Alamos venerated Bohr, but seemed not to take his worries, which he discussed at informal political meetings, too seriously: “I remember sitting on the floor in a group of awestruck listeners as Bohr agonized over the kind of world that would result from our grim work on nuclear energy. Actually much of the conversation was of playful nature; it scintillated.”) There was also growing evidence that the war in Europe would be over before the bomb project was completed.

Finally, towards the end of 1944, it became obvious that the Germans had abandoned their bomb project, and Rotblat asked to leave. Permission was granted — with the condition that the public reason for his departure would be concern for his wife Tola.

Back to the UK (1945-1955)

After a few incidents in which security personnel attempted to frame Rotblat as a communist spy, Rotblat returned to Liverpool to start rebuilding the physics department (and get his surviving family out of Poland).

When nuclear bombs were dropped in Japan, Rotblat (again) felt betrayed. He gave a series of lectures calling for a three-year moratorium on atomic research. He also founded the (British) Atomic Scientists Association and organized the “Atom Train”, a traveling exhibition on nuclear energy that was attended by 170,000 people.

Around this time, Rotblat decided that he wanted to make sure that his research would be used for the benefit of humanity and turned his focus towards medical physics.

Rotblat’s career would start transitioning into its next major stage when, in March 1954, the US’s Castle Bravo test in the Bikini Atoll exposed the Japanese fishing boat Fukuruyu Maru to unusually high levels of radioactive fallout. Rotblat published a paper demonstrating that the test’s radioactive contamination was far greater than what official statements claimed and appeared on a BBC program to discuss nuclear issues.

UK (1955 − 2005): advocate for peace

A year later (and partly as a result of events following the Castle Bravo test), Bertrand Russell asked Rotblat to become the 11th signatory of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto.

Russell had also become interested in hosting a series of international conferences of scientists to discuss nuclear nonproliferation and peace, but was struggling to find the right members and sources of funding. In 1957, Russell managed to gather the necessary components; Cyrus Eaton would sponsor a conference in his hometown, Pugwash, and Rotblat, together with Cecil Powell, would become the main organizer of the conference.

This became the first of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, which seem to have been quite influential. The conferences brought scientists from both sides of the Iron Curtain together — eventually also involving student groups and, after the conferences stopped being painted as fronts for Communist gatherings, high-level policymakers. They’re credited with laying the groundwork for the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963, the Nonproliferation Treaty of 1968, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty of 1972, the Biological Weapons Convention of 1972 and the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993. (For more, see this literature review and this case study.)

For the rest of his life, Rotblat dedicated himself to pursuing his mission: a world without war.

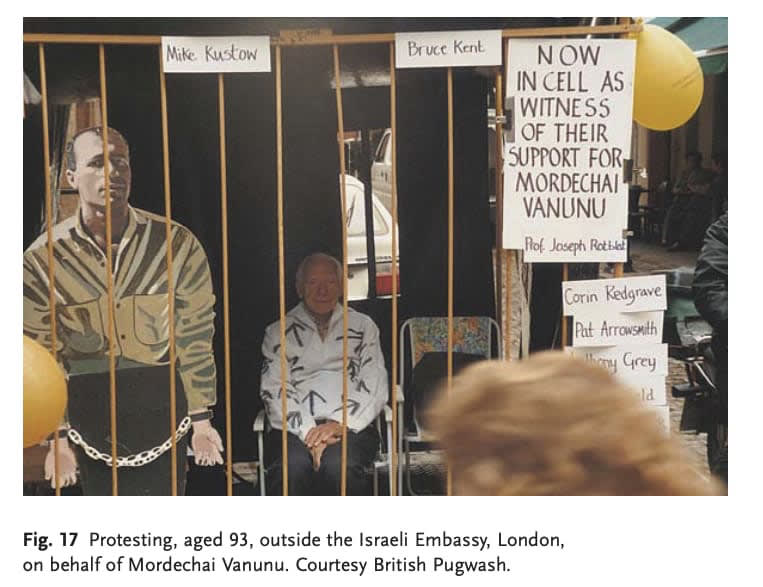

He helped to start the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), gave countless interviews and lectures on the moral responsibility of scientists and others, attempted to help draft a world constitution, spent time fundraising for and organizing this work, spoke out in defense of whistleblowers like Mordechai Vanunu, advised on the docudrama Threads, and more. I haven’t tried to carefully examine the impact of his work, but he seems to have directly inspired thousands of people.

And while in many ways, achieving Rotblat’s goals feels close to impossible, I agree with him that “even events that seem out of this world can be realized if we put enough effort and faith into them.”

Rotblat died on August 31, 2005, aged 96.

Some reflections

See also this comment (an exercise in giving myself advice).

Why was Rotblat the only scientist to leave the Manhattan Project (on moral grounds)?

Many of the hundreds of scientists who participated in the Manhattan Project later seemed to believe that in doing so, they had suspended or overridden their ethical views. (A good number had initially joined because they didn’t want the Nazis to be the first to develop nuclear weapons. And while Rotblat had gotten some of his information early, by the end of 1944 it was obvious that the Germans would not develop a bomb. Many would stay until the bombs were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in August of 1945.)

So I want to understand why Rotblat was the only one to leave at the time.

In “Leaving the Bomb Project,” Rotblat tries to explain why other scientists stayed on the project. According to him:

Many were driven by scientific curiosity. They wanted to see if the project worked, and convincing themselves to leave would have required overriding this impulse. (And the atmosphere was also probably just intellectually very gratifying.)

Many American lives would be saved if the bomb brought a rapid end to the war with Japan.

Fear of adverse effects on their future career probably prevented some from leaving.

And the “majority were not bothered by moral scruples; they were quite content to leave it to others to decide how their work would be used.”[5]

I expect that the background and psychological environment the scientists inhabited also played important parts. Rotblat’s circumstances here were unusual in a few significant ways:

Before being recruited to the Manhattan Project, Rotblat had independently thought through his reasons for and against working on the development of an atom bomb — unlike most of the others. He later believed that this might have given him a stronger sense of responsibility for the overall project, and I’d guess that thinking through a decision like this while already working on the project would have been a lot harder.

Rotblat was, I think, less embedded in the overall Los Alamos culture than many others. His English wasn’t perfect (he was especially close to people in similar situations), he was part of the British delegation (a minority), he lived, for some of his time there, with the Chadwicks instead of at the “big house” for single men, and from what I can tell, the uncertain fate of his family weighed very heavily on him. (Others, meanwhile, seemed to feel a lot of loyalty to Oppenheimer and felt a lot of camaraderie.)

And Rotblat had many conversations on moral and societal issues related to the bomb with Bohr — an extremely serious thinker who was quite early to worrying about a catastrophic arms race.

From what I can tell, Rotblat also had an unusual amount of “moral courage.”[6] I expect that this played a nontrivial role. (See this footnote for some notes on what Rotblat was like, based on the recollections of those who knew him.[7])

Quotes from Rotblat

(If you’re interested in reading more of Rotblat’s writing, consider starting with “An Allegiance to Humanity,” “Leaving the Bomb Project,” or his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech.)

I want to end this post with some excerpts from Rotblat’s writing.

I would describe myself as a realistic pacifist although this sounds like an oxymoron. [...] Even events that seem out of this world can be realized if we put enough effort and faith into them.

One such event is a world without war.

[...]

We all agree that life is our most precious commodity. We cannot bear the thought that human life can disappear from this planet, least of all, by the action of man.

And yet the impossible, the unimaginable, has now become possible. The future existence of the human species can no longer be guaranteed. The human species is now an endangered species.

[...]

We, the scientists who began the work on the atom bomb, did not believe that [acquiring the technical means to bring the whole of the human race to an end in a single act] could be the result of our work. When we began work on the atom bomb, we had a pretty good idea of its enormous destructive power. We knew about the blast, the heat wave, even about radioactive fallout. We knew that the use of the bomb could destroy a city like Hiroshima; and later on, that hydrogen bombs could destroy a city perhaps like New York. Even so, we felt it could not threaten humankind, because for this purpose it would need a very large number, perhaps 100,000 of these weapons.

Even in our most pessimistic scenarios we could not envision a situation in which such a huge number of weapons would be produced. We could see no purpose for that whatsoever. And yet, within quite a short time more than 100,000 nuclear weapons were accumulated by the United States and the Soviet Union.

The war psychology is that once we enter war, we lose our moral values and we are encouraged to kill people who were, in previous days, our partners and our friends. … This moral dilemma existed all the time, and is still going on up to this day.

Once you begin this game and work on this sort of work, then you lose some moral values. You become engrossed in dealing with gadgets and in inventing newer and newer gadgets.

[...]

A campaign for abolition based on moral principles will be seen as a fanciful dream by many. But the situation is grim; the way things are moving is bound to lead to catastrophe. If there is a way out, even if seemingly unrealistic, it is our duty to pursue it.

— Science and Nuclear Weapons: Where do we go from here?

And finally, from his Nobel Lecture (quoting from the Russell-Einstein Manifesto):

Above all, remember your humanity.

- ^

Wertenstein doesn’t have an English-language Wikipedia page, which saddens me. If changing that would be enjoyable to you, consider writing one!

- ^

He later believed that this reasoning was erroneous, as Hitler was crazy enough to use the bomb even in a hopeless situation.

- ^

Upon hearing the news, Rotblat had hitchhiked to the Polish embassy in London to see what he could do. The embassy, however, was in complete chaos; apparently they had asked him for advice.

- ^

p45 of Keeper of the Nuclear Conscience

- ^

Rotblat’s fourth point strengthens my sense that many Manhattan Project scientists were primarily thinking of the bomb as an abstract goal without engaging with it as a visceral reality. In “Niels Bohr and the young scientists,” for instance, Robert Wilson writes:

There is a vast difference between a logical possibility, even a logical certainty, and a demonstrated fact. It was not until I directly observed the test explosion on the Jornada del Muerto desert of New Mexico that I had a real, an existential, understanding of what we had been making. [...] As the message of the bomb’s actuality sank in deeper and deeper, it became clear that I — that we all — shared the kind of responsibility that Bohr had so perceptively been preaching about. Almost all of us changed gears almost immediately, began to discuss intensely the social dimensions of the problems before us [...]

- ^

These themes also seem to appear in the life of Benjamin Lay

- ^

When Rotblat died in 2005, Sandra Butcher, who’d interacted with him while at Pugwash, wrote an open letter to her then three-year-old son Joey, who was named after Rotblat (whom he knew as “Prof”). She writes:

… what, exactly, does that name stand for?

In my opinion, it stands for brilliance, compassion, patient optimism, humor, dogged determination, an insistence that we can all do better, energy, humility, youthfulness, and, above all, humanity.

...

Be a rebel, when it is for a good cause. Do not be constrained by limitations others set for you. Treat others with dignity and with loyalty. Stretch your mind and open your heart. Insist on an equitable world, and seek peace in every situation. Refuse to compromise your values. Laugh with others. Live simply and with meaning. Do not judge people by their titles or their age, but by their creativity and vivacity. Envision a long and productive life, and then exceed expectations. If you do all of these things, then you will honor the example set for you by Joseph Rotblat.

Some of the qualities that Rotblat apparently had stood out to me as I read the recollections of people who knew him (and generally about his life). I pulled some out in a list, focusing on qualities that I aspire to and which seem especially rare or under-appreciated:

(1) “Enduring optimism” and dedication to his mission

People described him as “obstinate” and “enduring.” He lived through a tragedy that I can’t imagine and saw the growing nuclear stockpiles of the world, but apparently maintained a hopeful view of the future and didn’t seem to waver in his dedication to his work.

(2) “Responsible dissidence”

He seemed to have been a very independent thinker, willing to disagree with his allies and with powerful people, but he managed to avoid developing reactionary beliefs, becoming embittered, and or approving of all “dissidents” in a blanket way. (Note: Rotblat apparently gave a seminar on “Swimming against the current: responsible dissidence” in March 2001 — a reference I saw in Keeper of the Nuclear Conscience listed RTBT K.288. If anyone can find this, I’d be grateful and very interested!)

He was also apparently steadfastly against propaganda and tribalism. E.g. he called out work that argued for conclusions that he supported, if its arguments or science were flawed.

(3) Humility and “innate courtesy”, and judging people (and ideas) on their merits, not their status

A lot of people mentioned something about this; later in his life, he seemed to have moved and impressed a lot of relatively junior people by treating them as equals and with seriousness.

(4) Willingness to do (a lot of) boring, low-status work

Even quite late in his career, he seemed to have volunteered to do administrative tasks that others didn’t want to take on.

(5) Pragmatic idealism

Many described him in similar terms. This includes himself — in “An Allegiance to Humanity” he writes: “I would describe myself as a realistic pacifist although this sounds like an oxymoron.”

In Keeper of the Nuclear Conscience, the author writes that:

There was a danger, he thought, in being labelled ‘extremist’ because people would then disregard your views, yet there was an equal danger in the rarified world of arms control talks where in order to be taken seriously by ‘realist’ opponents, you had to abandon dirty words like ‘disarmament’. Rotblat’s engaging image of the proper Pugwashite was one who held his head high, above the clouds, but kept his feet firmly on the ground.

Lessons/advice from Rotblat for Oscar (mainly for myself, sharing because of Lizka’s suggestion, written before reading Lizka’s specific advice, I suppose the similarities aren’t surprising given the content of the post)

Seek out advice from wise people you respect when making important decisions.

I remember when I was deciding whether to take an offer to intern at Jane Street I felt really conflicted and like I was somehow betraying my principles by working for a finance company and sought out advice from several (non-EA) older friends and mentors. I ended up deciding to take the offer, but I think it was a good process. Less positively, I recall just kind of drifting into the AI world and slowly finding AI risk arguments more compelling, but I think in retrospect I probably should have tried to find AI-risk-skeptical people (within and outside EA) to run things by more.

There are many fun and interesting intellectual challenges in the world! You can afford to turn down work on something that seems really challenging and exciting.

It is pretty hard to think about the counterfactual of what I would be doing if I had never been interested in altruism (maybe it is a nonsensical question, depending on one’s views of personal identity?) but my guess is I would be an academic mathematician or philosopher. But turns out there are plenty of interesting questions to think about outside of these fields as well! I’d like to imagine that even if medical physics wasn’t Rotblat’s top choice of the funnest intellectual field, that he found a lot of satisfaction in it regardless!

Social groups are powerful and amazing and dangerous.

I moved to Oxford earlier this year and meeting lots of interesting impressive new people has been great, but I can also feel my thinking being shaped by this milieu. E.g. maybe I am more reluctant than I should ideally be to work for a government, or go back to ETG, or generally go somewhere away from as high a density of EAs.

Thank you for writing this. I really appreciate EA’s focus on highlighting people doing the right thing out of good judgment. Normally people tend to focus on selflessness, courage and hard work instead of good judgment when they think of praiseworthy figures. These are also pretty important but it’s nice to learn more about people succeeding in this overlooked requirement for doing good.

Lovely writeup! Just to flag that a handful of others refused to work on the Manhattan project in the first place, including Lise Meitner and Franco Rasetti.

Addendum to the post: an exercise in giving myself advice

The ideas below aren’t new or very surprising, but I found it useful to sit down and write out some lessons for myself. Consider doing something similar; if you’re up for sharing what you write as a comment on this post, I’d be interested and grateful.

(1) Figure out my reasons for working on (major) projects and outline situations in which I would want myself to leave, ideally before getting started on the projects

I plan on trying to do this for any project that gives me any (ethical) doubts, and/or will take up at least 3 months of my full-time work. When possible, I also want to try sharing my notes with someone I trust. (I just did this. If you want to use my template / some notes, you can find it in this footnote.[1] Related: Staring into the abyss.)

(2) Notice potential (epistemic and moral) “risk factors” in my environment

In many ways, the environment at Los Alamos seemed to elevate the risk that participants would ignore their ethical concerns (probably partly by design). Besides the fact that they were working on a deadly weapon,

There was a lot of secrecy, and connections to people outside of the project were suspended

There was a decent amount of ~blanket admiration for the leaders of the project (and for some of the more senior scientists)

Relatedly, there was a sense of urgency and a collective mission (and there was a relatively clear set of “enemies” — this was during a war)

Based on how people wrote about Los Alamos later, there seemed to be something playful or adventurous about how many treated their work; the bomb was being called a “gadget,” their material needs were taken care of, etc.

And many of the participants were relatively young

(Related themes are also discussed in “Are you really in a race?”)

All else equal, I would like to avoid environments that exhibit these kinds of factors. But shunning them entirely seems impractical, so it seems worth finding ways to create some guardrails. Simply noticing that an environment poses these risks seems like it might already be quite useful. I think it would give me the chance to put myself on “high alert,” using that as a prompt to check back in with myself, talk to mentors, etc.

(3) Train some habits and mental motions

Reading about all of this made me want to do the following things more (and more deliberately):

Talking to people who aren’t embedded in my local/professional environment

And talking to people who think very independently or in unusual (relative to my immediate circles) ways, seriously considering their arguments and conclusions

(Also: remembering that I almost always have fallback options, and nurturing those options)

Explicitly prompting myself to take potential outcomes of my work seriously

Imagine my work’s impact is more significant than I expected it to be. How do I feel? Is there anything I’m embarrassed about, or that I wish I had done differently?

Training myself to say — and be willing to believe/entertain — things that might diminish my social status in my community

(This includes articulating confusion or uncertainty.)

I don’t have time right now to set up systems that could help me with these things, but I also just an event to my calendar, to try to figure out how I can do more of this. (E.g. I might want to add something like this to one of my weekly templates or just set up 1-2 recurring events.) Consider doing the same, if you’re in a similar situation.

And these ideas were generated very quickly — I’m sure there are more and likely better recommendations, so suggestions are welcome!

Here’s the rough format I just used:

(1) Why I’m doing what I’m doing

[Core worldview + 1-3 key goals, ideally including something that’s specific enough that people you know and like might disagree with it]

(2) Situations in which I would want myself to leave [these are not necessarily things that I (or you, if you’re filling this out) think are plausible!]

(2a) Specific red lines — I’d definitely leave if...

(2b) Red flags: very seriously consider leaving if...

(2c) [Optional] Other general notes on this (e.g. how changes in circumstances might affect why I’d leave)

My notes included hypothetical situations like learning something that would cause me to significantly update on the integrity of the people in charge of my organization, situations in which important sources of feedback (sources of correction) seemed to be getting getting closed off, etc.

Choosing ‘and’ or ‘or’ feels important here since they seem quite different! Maybe our rough model should be cause-for-introspection = ethical qualms * length of project

This is an awesome writeup. I find it really interesting that he was engaged with the WCC. Echoing Emre Kaplan, I really appreciate EA appreciating good people. Judgement is a very praiseworthy attribute.

Executive summary: Joseph Rotblat was a principled physicist who left the Manhattan Project on moral grounds and dedicated his life to nuclear disarmament and promoting global peace.

Key points:

Rotblat was the only scientist to leave the Manhattan Project voluntarily, motivated by ethical concerns about nuclear weapons

He founded the influential Pugwash Conferences, which helped negotiate multiple international arms control treaties

After World War II, he transitioned from nuclear physics to advocating for nuclear disarmament and global peace

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995 for his lifelong commitment to reducing nuclear threats

Rotblat exemplified “pragmatic idealism”—maintaining hope and dedication to seemingly impossible goals of world peace

He consistently prioritized moral responsibility and humanity over scientific achievement or personal career advancement

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.