A couple of EAs encouraged me to crosspost this here. I had been sitting on a shorter version of this essay for a long time and decided to publish this expanded version this month partly because of the accusations of eugenics leveraged against Nick Bostrom and the effective altruism community.

The piece is the first article on my substack and you can listen to me narrate it at that link. Note that I changed the title from the original piece to better fit the norms of EA forum.

You’re probably a eugenicist

Let me start this essay with a love story.

Susan and Patrick were a young German couple in love. But, the German state never allowed Susan and Patrick to get married. Shockingly, Patrick was imprisoned for years because of his sexual relationship with Susan.

Despite these obstacles, over the course of their relationship, Susan and Patrick had four children. Three of their children—Eric, Sarah, and Nancy—had severe problems: epilepsy, cognitive disabilities, and a congenital heart defect that required a transplant. The German state took away these children and placed them with foster families.

Patrick and Susan with their daughter Sofia—credit dpa picture alliance archive

Why did Germany do all these terrible things to Susan and Patrick?

Eugenics.

No, this story didn’t happen in Nazi Germany, it happened over the course of the last 20 years. But why haven’t you heard this story before?

Because Patrick and Susan are siblings.

One of the aims of eugenics is to intervene in reproduction so as to decrease the number of people born with serious disabilities or health problems. Susan and Patrick were much more likely than the average couple to have children with genetic problems because they are brother and sister. So, the German state punished this couple by restricting them from marriage, taking away their children, and forcefully separating them with Patrick’s imprisonment.

Patrick Stübing filed a case against Germany with the European Court on Human Rights, arguing that the laws forbidding opposite-sex sibling incest violated his rights to family life and sexual autonomy. The European Court on Human Rights’ majority opinion in the Stübing case clearly sets out the eugenic case for those laws: that the children of incest and their future children will suffer because of genetic problems. But the dissenting opinion argued that eugenics cannot be a valid justification for punishing incest because eugenics is associated with the Nazis, and because other people (for example, older mothers and people with genetic disorders) who have a high chance of producing children with genetic defects are not prevented from reproducing. Ultimately, the European Court on Human Rights upheld Germany’s anti-incest law on eugenic grounds.

If Germany had punished any other citizens this severely on eugenic grounds—for example by imprisoning a female carrier of Huntington’s disease who was trying to get pregnant— there would be a huge outcry. But incest seems to be an exception.

Our instinctive aversion to incest is informed by intuitive eugenics. Not only are we reflexively disgusted by the thought of having sex with our own blood relatives, but we’re also disgusted by the thought of any blood relatives having sex with each other.

Siblings and close relatives conceive children who are more likely to end up with two copies of the same defective genes, which makes those children more likely to inherit disabilities and health problems. It’s estimated that the children of sibling incest have a greater than 40 percent chance of either dying prematurely or being born with a severe impairment. By comparison, first cousins have around a five percent chance of having children with a genetic problem—twice as likely as unrelated couples. In the UK, first cousin marriages are legal and these unions make up a disproportionate number of babies born with birth defects including those who die shortly after birth, likely numbering thousands per year. In the US, most states have outlawed first cousin marriage for eugenic reasons. For instance, in states like Arizona first cousin marriage is allowed, provided the cousins are infertile or over the age of 65.

If you agree that people who are genetically related should not have children, or should see a genetic counselor, congratulations, you’re a eugenicist.

While we heavily weigh the risk of closely related parents, we often discount even more serious risks simply because they don’t have the same visceral emotional impact as incest. For instance, between five and six percent of first cousins pass genetic disorders on to their children, but a parent with Huntington’s disease has a 50 percent chance of passing on the disease to their child. If one parent has schizophrenia, their child has a 10 percent chance of inheriting it; with two schizophrenic parents, the likelihood is 40 percent.

This would be consequential enough on its own, but there is strong evidence that people with mental disorders, including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance abuse, are more likely to be in relationships with one another. These relationships, like relationships between blood relatives, entail a risk: the children that result are much more likely to share their parents’ misfortune, which not only increases the number of these disorders but also their comorbidity, or the likelihood that one person will suffer multiple disorders. Most governments forbid sibling incest, but do not even provide education to people who are just as likely to pass on other devastating heritable conditions. We treat similar or elevated risks dissimilarly based on our instinctive feelings of disgust.

Eugenics, a literal translation of the Greek for “good birth,” aims to improve the population through interventions. Positive eugenics aims to increase “good” and “desirable” traits, whereas negative eugenics aims to reduce “bad” or “undesirable” traits. The scare quotes are meant to indicate that there are and have been divergent views on the meaning of these words in the history of eugenic interventions. The taboos attached to even the most rational and objective discussion of eugenics only aggravates the confusion, promoting a widespread ignorance of even the definition of eugenics. Eugenics is actually an expansive concept with which most people agree in principle, but disagree with some of the terrible ways it’s been implemented. We are all eugenicists—but in selective, inconsistent, and often hypocritical ways.

In terms of the population, eugenics can be implemented at many different levels. Eugenics can be coercive and violate people’s freedom of mate choice and reproduction, but it can also be libertarian, relying on social influence, persuasion, and reproductive education. Consider the diverse goals of some historical eugenicists. Francis Galton (1822–1911), who coined the term, wanted to encourage geniuses to marry one another, so they could create a new “race” of super-smart people. The North Carolina Eugenics Board coerced thousands of Black women into getting sterilized. Progressive Black eugenicists like Kelly Miller (1863–1939) and W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) wanted to encourage educated Black families to have more children to uplift Black Americans. Chinese sociologist Pan Guangdan (1898–1967) wanted to improve the overall health of the Chinese people (and helped to eradicate foot binding). Nazis murdered thousands of disabled people and others who were considered genetically defective. Rabbi Joseph Ekstein founded Dor Yeshorim in 1983 to reduce debilitating genetic diseases such as Tay-Sachs and Cystic Fibrosis in Jewish families. The first prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew (1923–2015) arranged matchmaking cruises for university graduates, and gave women graduates priority housing, in an attempt to increase the number of educated Singaporeans in the next generation.

“Good” also has different definitions. During this moment in history, “good” depends on whether you’re endorsing changing something genetically or environmentally. Most people agree that that being healthy, educated, happy, stable, intelligent, altruistic, and productive are good qualities. When it comes to preventing disability and increasing IQ, almost every environmental intervention is uncontroversially considered. We encourage people with mental health problems to take medication that may help them suffer less and become more productive. We take children away from families that neglect or mistreat them, not only so they do not suffer now, but also so they are more likely to become intelligent, productive members of society. We discourage harmful behavior with prison, fines, penalties, social disapproval, and exclusion and encourage altruistic behavior with social approval and tax incentives. Pregnant women and mothers bear much of the burden of trying to produce kids with good traits; any decision that might influence children, from drinking while pregnant to childhood nutrition, from the Mozart effect to video games, is moralized and supervised. Though there is very little evidence that some of these environmental interventions make much difference.

Historically, eugenicists were focused not only on genetically heritable characteristics but also potentially effective environmental and cultural influences on children’s traits. Chinese eugenicists led the charge to eradicate foot binding, and implemented programs of maternal education so they could provide better care for infants. Eugenicists also initiated the mandatory treatment of infectious diseases like syphilis, which causes blindness, deafness, and cognitive disability. If you think women should be treated for sexually transmitted infections or rubella so they don’t have a disabled child, you’re advocating the same goals as many historical eugenicists.

Those who rail against eugenics in any form engage in a technique where they conflate an easily defended position with a more difficult to defend position (AKA the Motte and Bailey strategy). The easily defended position is that we should not murder or forcibly sterilize people on the basis of their genetics or disability. This position is conflated with several more difficult-to-defend positions. These more difficult-to-defend positions include that we should not study the genetics of desirable or undesirable characteristics, that we should not label any characteristics as desirable or undesirable and that we should not consider how any policy could change the genetic propensities of future generations.

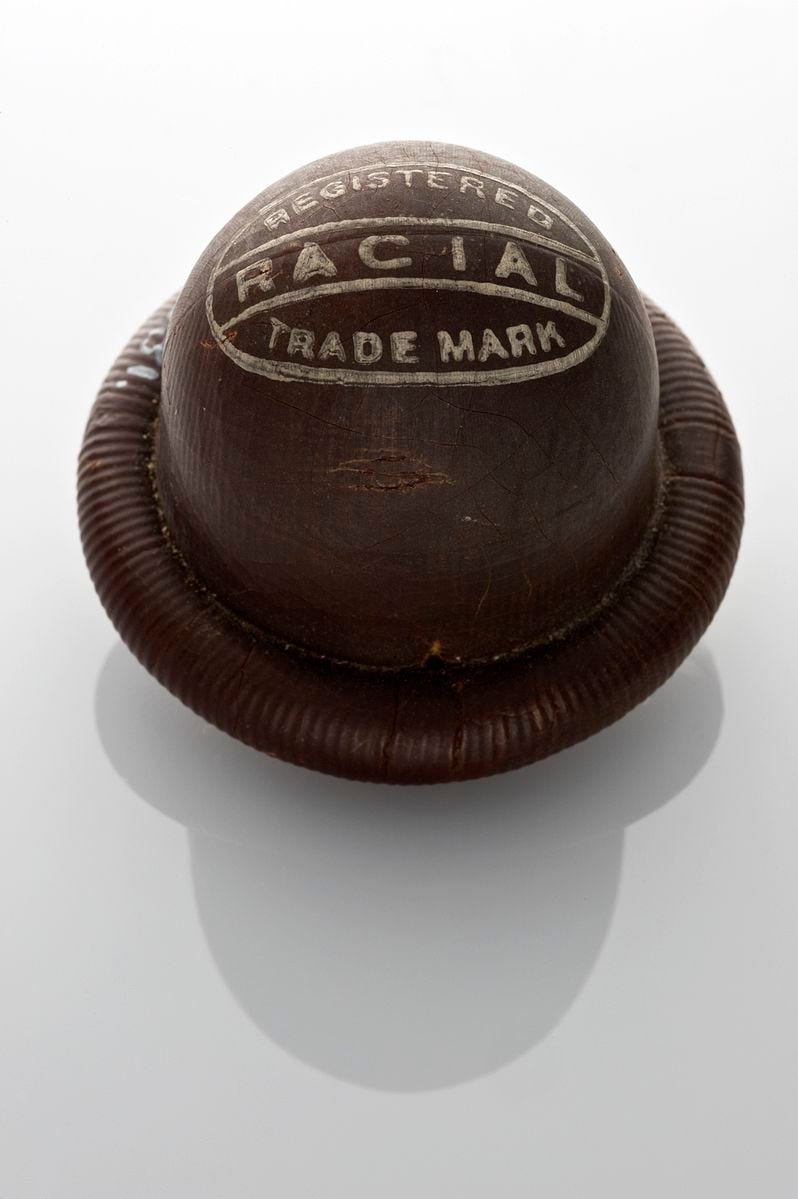

It is inevitable that good or neutral ideas will sometimes be misused for terrible ends by bad actors. Despite the popular treatment of eugenics, the concept of eugenics is not synonymous with the worst things that have been done in its name. Consider other concepts we embrace in spite of their history of misuse. That democracies voted for slavery and have sent men to their deaths in needless wars does not invalidate the idea of government by consent. Psychiatry invented lobotomy and facilitated imprisonment and Soviet atrocities. Foster care removed indigenous children from their parents. In the case of contraception and abortion, progressives are willing to overlook the association with eugenics because of what they see as positive outcomes. Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger were both eugenicists who wanted to prevent the unfit from breeding and also founded the organization that would become Planned Parenthood. Their transparently eugenic aims to improve the human race are literally written right on the contraception that they dispensed, the “pro race” and “racial” models of cervical caps. Even now, there is evidence that the legalization of abortion had eugenic effects and many states and countries, before Roe was overturned outlawed abortions on anti-eugenics grounds.

A cervical cap stamped with “Racial” indicating its use as a tool of eugenics—via Wellcome Trust

Unlike eugenics, every conversation about democracy, foster care, psychiatry, or contraception do not devolve into outrage about how they are slippery slopes to genocide, mutilation, and racism. We ought to be capable of decoupling the history of a concept from its intention if the potential outcomes are good enough.

You might be asking yourself- why use the term “eugenics” at all? Can’t you just call it something different?

Well, not really.

We are not going to stop hearing about eugenics. Every time someone tries to call it something different, the “e” word and its association with historic injustice and abuse is invoked to end the discussion before it can begin.

When someone says that screening embryos for genetic diseases, giving educated women incentives to have children (like free child care for college educated women), or offering subsidized abortions for women addicted to drugs is “eugenics” they are absolutely using the term correctly. If bioethicists stopped using terms with contested definitions there would only be confusing new terms that would lead to a euphemism treadmill. All of the following key terms (to name just a few) have contested definitions and using them can cause confusion: autonomy, bioethics, consent, euthanasia, freedom, harm, health, justice and person. In my view, the only way to have a reasonable conversation about reproductive issues is to educate people on the meaning of eugenics. This tactic arguably also promoted clarity in the debate about “euthanasia”.

Even though many people have tried to redefine any personal choices, and especially the personal reproductive choices of women as “not eugenics”, there is not a clear delineation between public policy and private choice. I discovered during my pregnancy how many default aspects of prenatal care are eugenic in their aims. A lot of prenatal care aims to evaluate an embryo or fetus for abnormality. A woman can “terminate for medical reasons”, a right that progressives would never dispute. Yes, terminating for medical reasons is a personal choice. But during my pregnancies I was not asked whether I wanted noninvasive prenatal testing, a nuchal translucency scan or genetic counseling for advanced maternal age; they were provided to me as a matter of course as they are provided by most countries with nationalized health care.

Eugenics concerns the decisions of individuals, not just the policies of the state. “Reprogenetics” uses reproductive technology to allow parents to select embryos with certain desirable traits or without disability. In the future, Parents are now able to select embryos with desirable characteristics. Both practices meet the definition of eugenics. But reprogenetics will have an even greater influence on the population as a whole when these techniques are more accessible and affordable.

Many of the same controversies around eugenics also apply, in principle, to reprogenetics. For example, the “expressivist objection” to reprogenetics is that, by using prenatal testing to try to choose a child without disability, we are expressing a discriminatory stance against disabled people. Anti-eugenic and anti-reprogenetics arguments often imply that when we reduce the number of disabled people in the population, bias against disabled people increases in society. But pursuit of this peculiar logic leads to repugnant conclusions, which may be exposed by applying the reversal test. Should we encourage pregnant women to drink alcohol and use drugs, or encourage drivers to forgo seat belts, in order to cultivate greater care and consideration when these acts result in more disabled people? Care and respect for disabled people can coexist with eugenics, as is demonstrated in Israel where prenatal testing is largely uncontroversial. As sociologist Aviad Raz stated, “There is a two-fold view of disability [in Israel]: support of genetic testing during pregnancy, and support of the disabled person after birth.”

Given how closely eugenics has been associated with Nazis and the Holocaust, it is interesting to consider the degree to which Jewish people have embraced eugenics. I wouldn’t be here to write this essay had my Jewish grandfather not fled the Nazis in the 1930s. The Talmud expressed eugenic principles about who could marry whom—for example, it is forbidden for a woman to marry a man with epilepsy— German genetic counselors are much more likely to express disapproval for eugenic principles than Israeli genetic counsellors. Israeli genetic counselors are more likely to endorse statements such as “it is socially irresponsible to knowingly give birth to an infant with a serious genetic disorder” and “it is important to reduce the number of deleterious genes in a population.” The Israeli National Program for the Detection and Prevention of Birth Defects offers free testing for many genetic diseases, and Israeli women are more likely to get tested than women in other countries.

Moreover, countries and states who have implemented eugenic policy offer evidence against the idea that this is a slippery slope to abuses like murder and forced sterilization —Israel and Denmark two countries that have some of the most eugenic policies, also have some of the best provisioning for the disabled. States like Oregon, Nevada, Minnesota and Texas that have implemented eugenic laws against first cousin marriage nevertheless have very different reproductive and disability policies. In Oregon, women can have an abortion at any stage of pregnancy and for any reason and terminally ill patients can access physician assisted suicide. In Texas, the opposite policies are in place.

Despite the history of Nazi eugenics, Jews and the state of Israel embrace eugenic policies. The most comprehensive noninvasive fetal genotyping available at 11 weeks was developed in Israel. Further, abortions are legal and free in Israel if a fetus is found to have a genetic defect. While fewer abortions are performed in Israel than in other affluent countries, a much greater proportion of abortions are performed due to risk of birth defects. Orthodox Jews who oppose abortion use premarital genetic testing instead—an organization like Dor Yeshorim tests couples for genetic compatibility based on the likelihood that they will produce children with genetic problems such as Tay-Sachs. This eugenic match-making is very similar to George Church’s widely criticized “digid8” app. As geneticist Raphael Falk put it, “Whereas in Nazi Germany Jewish life was systematically destroyed in the name of eugenics, Zionists in the Land of Israel conceived of eugenics as part of their mission to restore the Jewish people.” Do you agree that women should be allowed to abort embryos with genetic defects or that couples from a small genetic pool, like Ashkenazi Jews, should be allowed to seek out genetic counseling before they marry? With regard to these issues, you’re a eugenicist.

But what about couples who can’t naturally have children on their own? Gay men and lesbian women were persecuted for so-called eugenic reasons during the horrific history of Nazi homophobia. Nevertheless, gay men and lesbian women in the US often use gamete donors from egg and sperm banks to have kids in a process that is transparently eugenic. From my experience as an egg donor, and from conversations with the many other egg donors I know, gay men often pay the most for eggs from “high quality donors”.

They prize attractive, high IQ donors even more than opposite sex couples do. Organizations that recruit egg and sperm donors don’t just recruit for fertility, they also screen for mental and physical health, height, education, and criminal history—because that’s what their clients want and expect.

When these eugenic expectations are betrayed, gamete banks are severely criticized and may find themselves in legal jeopardy. In 2003, a lesbian couple, Wendy and Janet Norman, purchased sperm from a bank that promised their sample was sourced from a mentally stable, upstanding citizen pursuing a PhD. But the sperm donor lied; he did not disclose his struggles with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, suicidal thoughts, and even obtaining an education. Nor did he disclose that he had served time in prison for burglary and that he was collecting disability for his mental illness. Wendy and Janet’s son has a significant mental disorder, violent tendencies, and suicidal thoughts. Based on genetics, it’s likely that three or four of the 36 children fathered by this sperm donor will suffer from schizophrenia. Behavioral genetics research also indicates that these children will be much more likely to have other mental illnesses and will be more likely to commit crime than if they had actually been fathered by a PhD with no mental illness and no criminal record. Janet and Wendy sued Xytex, the sperm bank they used, for false advertising. Their case and 12 other cases against the company have all been settled or dismissed.

If you think it’s good for egg and sperm banks to screen donors for disability or mental health problems, you’re a eugenicist. If you think it is right for the government to punish gamete vendors who do not adequately screen for such problems, you’re a eugenicist. If you think it makes sense that customers would want gametes from mentally stable people without a criminal record, you’re a eugenicist. If you’re truly anti-eugenics, you should think that this lawsuit against Xytex is illegitimate and deeply immoral. Many Jewish people, lesbian mothers, and gay fathers have embraced modern eugenics in the domain of choosing their children’s genes, even though eugenics has in the past been associated with discrimination against people like them.

There is nothing especially strange about screening one’s own children for disability, choosing an egg or sperm donor based upon their personal history and characteristics, or receiving genetic counseling. The clients of egg and sperm banks are doing explicitly what many of us do intuitively. What young couple hasn’t talked about what their children might be like? They wonder whether their child might inherit a sharp wit or a knack for mechanics. We often choose the people we have children with, in part, because we hope the things we love about them will pass on to the next generation. It’s normal for people to consider the personality and the physical and mental health of the opposite sex partners of their sons and daughters or sisters and brothers. This too, is eugenics.

There are very positive mainstream bioethical treatments of eugenics. Philosophers like Peter Singer and Julian Savulescu have argued that if we would do anything to make our children happy and successful in their upbringing, we also have a moral imperative to do everything we can to genetically facilitate those outcomes. Thomas Douglas and Katrien Devolder have made an altruistic moral case that we should try—environmentally and genetically—to create children that are the most likely to benefit society and the world and the least likely to cause harm to others. And yet most intellectuals are either too ignorant or afraid of public reproach to give these ideas an open hearing.

As I said, we are not going to stop hearing about eugenics. Those unable to get past “OMG it’s eugenics” should be aware that they are ceding the discussion of social policy and reprogenetics to the people who can. If this topic is discussed openly, we can ensure that it is conducted with a deep consideration of our moral values and acknowledgement of our human biases and moral flaws. To justify the consideration of the genetics of future generations and even their biological enhancement doesn’t mean resuscitating master race theories or a contemptuous disregard for the value of human life and autonomy any more than it does for psychiatry, foster care, and contraception.

The scientific consensus is that nearly all traits of importance, certainly including psychological characteristics have a substantial genetic component including the characteristics that enable our individual well-being, like mental and physical health and those that influence others’ well being, like productivity, intelligence, and compassion.

Nearly every social policy has some influence on who has kids and how many kids they have, from prison to free tuition, from abortion waiting periods to free prenatal care. But the taboos attached to the very concept of eugenics are thwarting important discussions about how we improve our shared future. Instead of acknowledging the potential of eugenic policies to improve lives, the state chooses brutal remedial methods like prison or the lottery of foster care. In the case of Patrick Stübing, the state could have just offered to pay him to get a vasectomy, a choice he ended up making anyway, instead of throwing him in prison. More benevolent methods like free or incentivized contraception are rarely used to ameliorate these problems because anything that sounds like eugenics is dismissed out of hand. This moratorium on discussing eugenics prevents clarity of thought in how policy influences reproductive choices and how these reproductive choices have a deep impact on the future. If we are willing to disrupt people’s lives, to make them suffer, to collect their wages, or alternatively to reward people and give them incentives, shouldn’t we permit conversations about how this will influence the character of future people?

The scientific consensus on behavioral genetics should allow us to appreciate that genes and reproduction will have a huge effect on the flourishing of future generations. Those who reflexively denounce any attempt at changing the genetic composition of the next generation—whether through genetically informed dating apps or government incentives—are defending the status quo at the expense of potentially valuable progress and causing harm we cannot fully appreciate. Only when our conversations about morality and obligation move past the mere mention of eugenics can we unlock an important means of improving the world.

Looking at the agree votes it seems that

mostmany people think a different word should be substituted for eugenics. I pointed out the problems with this in the piece, that eugenics already has a definition that both encompasses Nazi atrocities and things that most people agree with. And other words, like reprogenetics, liberal eugenics and procreative beneficence haven’t caught on. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that many reasonable people decide to phase out ‘eugenic’ and instead use a word like epilogenics (like @aella suggests here.) How would that work rhetorically?EA Bioethicist: Depression costs a huge number of QUALYs so I suggest the government subsidizes polygenic screening of embryos for depression for people who have suffered from depression and who are going through IVF.

Critic: That’s eugenics.

EA Bioethicist: Yes, technically it is. But we don’t use that word anymore. It’s actually “epilogenics” because people have free choice.

Critic: The fact that it also qualifies as a word you just made up doesn’t stop it from being eugenics.

This is a toy example but what if we freely used the word eugenics to describe all the things that it describes rather than putting a new label on just those things we agree with (without getting into the fact that it’s difficult to draw a bright line between coercive and non coercive interventions)?

EA bioethicist says the same thing about depression screening as above

Critic: That’s eugenics.

EA Bioethicist: Yes. But eugenics also encompasses many things you probably endorse, like genetic counseling for people with debilitating genetic diseases and laws against close relatives having children etc. So, “that’s eugenics” isn’t, by itself, an argument against my position.

Trying to hold onto the word “eugenics” seems to indicate an unrealistically optimistic belief in people’s capacity to tolerate semantics. Letting go is a matter of will, not reason.

E.g., I pity the leftist who thinks they can, in every conversation with a non-comrade, explain the difference between the theory of a classless society, the history of ostensibly communist regimes committing omnicide, and the hitherto unrealised practice of “real communism” (outside of a few scores of 20th-century Israeli villages and towns). To avoid the reverse problem when discussing “communist” regimes, I refer to “authoritarian regimes with command economies”. And I’m convinced it’s almost always better to go with “Social Democracy”.

Who cares if no other word has caught on yet. Marketing is a great and powerful force (one EAs seem only dimly to understand). Use more words if you have to. The key point is that “it’s a good idea to avoid tying yourself to words where the most common use is associated with mass murder.” [1]

Turning to the example. I’d pray to Hedone that most EAs can read the room well enough to avoid making such arguments while we still have nuclear wars to stop, pandemics to prevent, diseases to cure, global poverty to stamp out, and many cheap and largely uncontroversial treatments for depression and everyday sadness we’ve yet to scale. But assuming they did make that argument, I think the response to “That’s eugenics” should be something like:

“No, eugenics is associated with stripping a group of people of their right to reproduce. I’m discussing supporting families to make choices about their children’s health. Screening is already supported for many debilitating health conditions because of the suffering they produce, I’m saying that we should provide that same support when the conditions that produce the suffering are mental rather than physical.”

But maybe a takeaway here is: “don’t feed the trolls”?

Note: One response is, “we can’t give up on every word once it’s tainted by associated with some unseemly set of disreputes.” And that’s fair. For instance, I’m fine being associated with “Happiness Science” because the most common use is associated with social science into self-reported wellbeing, not a genocide-denying Japanese cult. The point is that choice of association depends on what most people associate the word with. Language will always be more bottom-up than top-down and seems much closer to a rowdy democracy than a sober technocracy.

Ah, you made the same point I did, but better :-)

I think it’s a good thing that most people have a revulsion towards the Nazi version of eugenics. I think trying to rehabilitate the word “eugenics” could plausibly lead to a lessening of that revulsion and and increase in support for their version. Just use a different word for the thing that’s okay, and that all goes away.

This feels a bit like a pro-taxation person hearing the argument that taxation is theft, and then going on to proudly declare that “everyone is a thief”, that everybody should be pro-theft (but only good theft), and we should rehabilitate the word “theft”. Just use a different word.

First- I’m not trying to rehabilitate murder, forced sterilizations or nazis. “Nazi eugenics” still has the word “Nazi” in it, which so far as I’m aware, no one is trying to rehabilitate.

Second- there is a case study for rehabilitation of a word, euthanasia. Euthanasia is associated with Nazis but now the word euthanasia is used in bioethics and public conversations freely for the practice of allowing people to die who are experiencing tremendous suffering. So far as I’m aware the rehabilitation of the word euthanasia has not resulted in people being more inclined to recommend the murder of the ill or disabled. Rehabilitation of the word euthanasia has instead resulted in a better conversation and provisions around the fate of people who are suffering.

Edited to add: This comment fails to reckon with the possible benefits of rehabilitating the word eugenics. When the word is used against reproductive technologies, individual reproductive choices and behavioral genetics it stifles conversation, debate and progress.

“euthanasia” was a euphemism the nazi’s used for their eugenics program. “eugenics” was a guiding principle of the Nazi ideology, as well as many other racist policies throughout the world, and continues to be used by neo-nazis to this day.

Trying to rehabilitate the word “eugenics” is like someone trying to rehabilitate the swastika symbol by waving a sanksrit version it around and insisting it means prosperity and good luck. It’s not gonna work, it’s going to offend and upset people, and people are gonna think you’re a Nazi.

It’s interesting that you say that anti-eugenicists are engaging in a motte and bailey argument, looking to tar less oppressive eugenicist practices with the brush of Nazi oppression. As I was reading through this, I worry that the attempted reclamation of the word ‘eugenics’ - as well as making “eugenicists” unpopular—might contribute to a motte and bailey in the other direction, where the motte is “surely you think it’s reasonable to prevent siblings from having kids” and the bailey is more oppressive or coercie forms of reproductive control.

Like, you start the essay with an example of “eugenics” that most people would agree was reasonable -a German court’s attempt to break up a couple of biological siblings. And then later, you talk about Nazi atrocities like murder and sterilization, which I agree that few modern eugenicists advocate for. But between those, you talk about people with mental illness: how bipolar, schizophrenia and substance abuse tendencies are genetic and often passed down to kids. You point out that people with these conditions often get together with others with the same condition, making their kids extra likely to have the disorder.

This perturbs me: is this, for you, in the reasonable ‘siblings’ camp or the unreasonable ‘Nazi atrocities’ camp? I can think of very mild interventions and very repressive ones, and I don’t think you say what you’d actually recommend here. In general, I love and admire people with mental disorders like this (including bipolar and substance abuse), and I think that reproductive rights are extremely important. I would feel sad if a bipolar friend, e.g., was strongly discouraged or even forcibly prevented from having children due to their condition, or if they were encouraged to seek out non-bipolar partners. I’d be against even mild “eugenicist” interventions aimed at making mentally ill people have fewer children.

I think most EAs are either positive or neutral about existence per se, and I think most people who are alive are happy to be, even if they struggle with difficult or painful mental and physical health conditions.

“I would feel sad if a bipolar friend, e.g., was strongly discouraged or even forcibly prevented from having children due to their condition, or if they were encouraged to seek out non-bipolar partners.”

I would personally feel much more sad if a child was born with a horrible and debilitating disorder unnecessarily.

People with bipolar tend to have a very low quality of life, lower than most other disabilities, and experience lower functioning and well-being even in the stable phase of the disorder. I’m probably neutral/ lean-positive about existence in general, but I am fairly convinced that bringing someone into the world knowing that they have a very high chance of bipolar disorder is a major moral harm, especially when adoption/ surrogacy/ embryo selection present safer options.

Let’s apply the reversal test to your assertion that you’d be “against even mild “eugenicist” interventions aimed at making mentally ill people have fewer children”. Would you be in favor of an organization that gave drugs to people with mental illness that made them more fertile?

All I’m endorsing in this essay is that interventions should be discussed, not any particular intervention. Personally, I would also be against the government intervening in the reproduction of people who want to have children. At the moment, someone with serious mental illness can have multiple children in foster care, have no desire to have children and still, as an accident of sex, have children they cannot care for who, moreover, are more likely to have inherited their problems. This is the basic idea behind Project Prevention- $300 is likely enough of a nudge that it incentivizes someone to take contraception who already does not want children. $300 is unlikely to convince someone who wants to have a child not to. Moreover, most PP clients choose reversible contraception.

There are countries that subsidize IVF. In the near future it could be possible for the government to subsidize polygenic screening for people with heritable conditions who do not want to pass these conditions down to their children. As I know many people with mental illness who choose not to have children because they don’t want their kids to share their misfortune, this could be an intervention that would help mentally ill people who want to have children have (more) children.

Re the reversal test, I’d be in favour of organizations that generally helped people become more fertile, if they wanted to be? I don’t want people with mental illness to have more children per se—I want them to have the amount of children they want to have.

I think in the case of Project Prevention, the question is muddied in several ways. If a person has lots of children but can’t or doesn’t take care of them, I agree that’s a problem, but it’s not really a eugenics issue (it would also be a problem if they had no mental illness and were just negligent). Conversely, if a drug addict had a lot of children but did take care of them, that’s not obviously an issue to me. And based on the wikipedia page, Project Prevention seems like a good example for why people are concerned about the reclamation of “eugenics”. The founder is quoted as saying “We don’t allow dogs to breed. We spay them. We neuter them. We try to keep them from having unwanted puppies, and yet these women are literally having litters of children”. This is incredibly dehumanizing language and doesn’t give me confidence that this person has drug addicts’ interests at heart! Her reply to criticism about this was that she cared about the children. But to me, the fact that the children may not have a stable home or reliable parent figure seems more important than their genetics.

I’d be in favour of polygenic screening for people with heritable conditions, as this really does seem to enhance parental choice and it comes from a place of compassion rather than stigma.

One doesn’t need to be a full Malthusian to think that adding severely impaired/relatively unproductive people to a population with a strong welfare state would counterfactually reduce the number of other people who would exist.

Also I basically don’t believe your claim. I think it has huge selection bias behind it. In the highly developed world in which I live I’ve met many people who seemed unhappy with their lives, and it’s hard to believe the less affluent world (the hypermajority) is better off. I might be wrong, but I don’t think you should treat it as a given that adding a person is a positive even holding all else equal.

We’ve had several decades of research on subjective well-being around the world. The big takeaway is that most people are (surprisingly) happy, even in poor countries, and that almost everybody experiences net positive utility.

The real selection bias is that isolated, alienated, single, childless, careerist, consumerist Westerners imagine that everybody else shares their depression & anxiety.

A note on the “positive utility” bit. I am very uncertain about this. We don’t really know where on subjective wellbeing scales people construe wellbeing to go from positive to negative. My best bet is around 2.5 on a 0 to 10 scale. This would indicate that ~18% of people in SSA or South Asia have lives with negative wellbeing if what we care about is life satisfaction (debatable). For the world, this means 11%, which is similar to McAskill’s guess of 10% in WWOTF.

And insofar as happiness is separate from life satisfaction. It’s very rare for a country, on average, to report being more unhappy than happy.

This is interesting! What is your guess of 2.5/10 based on? I guess this fuzziness makes me feel innately sceptical about such scales—I think one can get well-calibrated at tracking mood or wellbeing with numbers, but I think if you just ask a person who hasn’t done this, I wouldn’t expect Person A’s 5 and Person B’s 5 to be the same.

The guess is based on a recent (unpublished and not sure I can cite) survey that I think did the best job yet at eliciting people’s views on the neutral point in three countries (two LMICs).

I agree it’s a big ask to get people to use the exact same scales. But I find it reassuring that populations who we wouldn’t be surprised as having the best and worst lives tend to rate themselves as having about the best and worst lives that a 0 to 10 scale allows (Afghanis at ~2/10 and Finns at ~8/10.

That’s not to dismiss the concern. I think it’s plausible that there are systematic differences in scale use (non-systematic differences would wash out statistically). Still, I think people self-reporting about their wellbeing is informative enough to find and fix the issues rather than give up.

For those somehow interested in this nerdy aside, for further reading see Kaiser & Oswald (2022) on whether subjective scales behave how we’d expect (they do), Plant (2020) on the comparability of subjective scales, and Kaiser & Vendrik (2022) on how threatened subjective scales are to divergences from the linearity assumption (not terribly).

Full disclosure: I’m a researcher at the Happier Lives Institute, which does cause prioritization research using subjective well-being data, so it’s probably not surprising I’m defending the use of this type of data.

The research I’ve seen has done nothing convincing to control for a) selection people having to be in a sufficiently positive frame of mind to take surveys (what exactly is the inverse selection effect you imagine from Westerners?), b) social desirability bias (being happy is attractive—of course we want to announce it!), or c) the hopeless task of communicating positive valence in a standardised way to different global cultures.

In the west I think being willing to spend time to fill in a survey in return for $1.00 is probably a negative selection effect. Happy people are too busy being awesome.

What is “net positive utility”? What is the zero point?

Life satisfaction for people with disabilities has been well studied. It is lower than people without disabilities (in most cases), but is not zero.

(A handful of sources to start with: paper on disabled people in Germany that shows happiness recovers after disability, paper on Spanish people with intellectual disabilities shows they are largely satisfied with their lives, the average life satisfaction of people with disabilities in Northern Ireland is 7⁄10, across EU member states it’s between 6.2 and 7 out of ten.)

This seems like a reiteration of Geoffrey Miller’s comment, so all the discussion there applies.

I’m not sure that adding impaired/unproductive people would counterfactually reduce others—if a person with a disability refrains from having a child, that doesn’t mean that some healthy person elsewhere has an extra child.

Re being happy to be alive, I kind of want to distinguish ‘being unhappy with one’s life’ and ‘being happy to be alive’. I think you can have net-negative wellbeing and broadly think your life sucks, but still not sincerely want to die, or wish you’d never been born. This hunch is mainly based on my own experience: I’ve had times in my life where I think my wellbeing was net-negative, but I still didn’t wish I hadn’t been born. Basically I have a sense that there’s a value to my life that’s not straightforwardly related to my wellbeing.

It means there are fewer resources to go around, which fractionally disincentivises ~8 billion people from the expensive act of reproduction.

This claim makes strong philosophical assumptions. One could question what it even means to either ‘not wish you’d never been born’ or to ‘not want to die when’ when your wellbeing is negative.

One could also claim on a hedonic view that, whatever it means to want not to die, having net-negative wellbeing is the salient point and in an ideal world you would painlessly stop existing. This sounds controversial for humans, but we do it all the time with our pets: throughout their lives, they will fight for survival if put in a threatening state, but if we think they’re suffering too much we will override their desires and take them for one last visit to the vet.

Given that the lived experience of some (most?) of the people who live lives full of suffering is different from tha model, this suggests that the model is just wrong.

The idea of modeling people as having a single utility that can be negative and thus make their lives “not worth living” is way too simplistic.

I don’t want to give too much detail on a public forum, but I myself am also an example of how this model fails miserably.

What do you mean ‘the model is wrong’? You seem to be confusing functions (morality) with parameters (epistemics).

It’s also necessary if you want your functions to be quantitative. Maybe you don’t, but then the whole edifice of EA becomes extremely hard to justify.

If the phrase “Most people have net-positive utility” is rephrased as “most people don’t actively want to not exist” it sounds totally unsurprising, and not nearly as positive as the original sentence. Moreover, it doesn’t seem to be the definition most utilitarians use: For example, “It’s okay to create people as long as they will have net positive utility” would lose all intuitive support if transformed into “It’s okay to create people as long as they won’t actively want to not exist, even if their lives are filled with suffering”.

I’m inclined to consider it far more counterintuitive to think ‘if this person experiences overall slightly more negative than positive affect, but very much wants to live, and find their life meaningful, and I painlessly murder them in their sleep, then I have done them a favor’, which is what a purely hedonist account of individual well-being implies. (Note that this is about what is good for them, not what you morally ought to do, so standard utilitarian stuff about why actually murdering people will nearly always decrease overall utility across all people is true but irrelevant.)

Also in general I’m happy to treat humans as having substantially higher instrumental worth than animals for the increase to human capital, but the effect on net global utility of adding a seriously mentally ill probably omniverous person to the world seems likely to be quite negative even if you think that person’s welfare is net positive.

Thanks for this. I’ve been interested in this topic for a while as well.

As you mention China a bit in the article, I think it’s worth mentioning how “eugenics” is viewed in China at the moment.

The term eugenics (优生 yousheng or 优生学 youshengxue) has never really been taboo in China. You see it all the time—in political slogans and everyday speech—with more connection with modern medicine than the Nazis. You‘ll see crudely scribbled messages using eugenic language all over the countryside (the most common, until recently, being 少生优生,幸福一生 shaosheng yousheng, xingfu yisheng; translated as “Have few(er) and high(er)-quality (eugenic) children, and be happy your whole life!). You’ll also hear TV hosts and politicians discussing youshengxue as if it were as anodyne a concept as entomology. This forum post would read as nonsense to many Chinese people (the title would read as something like: “Most people endorse having healthy children”). You do get some exceptions, especially among foreign-educated people (see this Zhihu response (Chinese)), and I’m also unsure what (more western-influenced) HK/ Taiwanese people think about it.

The Baidu Baike (Chinese Wikipedia) first line is: “优生/Eugenics is the most important issue concerning marriages and families, it is a science that uses the principles of genetics to guarantee the normal survival ability of the next generation.” The ‘dark history’ of eugenics, particularly in Nazi Germany is mentioned briefly in one paragraph. See also the “Chinese Healthy Birth Science Association” http://www.chbsa.org/ (w/ google translate 中国优生科学协会 is “Chinese Eugenics Science Association”) website, with articles on a range of topics, from genetic testing to child nutrition.

I guess you could argue either way here. You could say that in China it’s good that you’re actually allowed to talk about this sensitive topic openly and rationally, without having a ridiculous and illogical cached concept where ‘wanting to have healthier children = nazi race science’. This is generally my experience and makes way more sense to me personally. If someone has distinctly dodgy views (spoiler alert: they do), you can argue with them without anyone using ‘but that’s eugenics’ to end the argument without actually addressing the issues.

But, from a consequentialist perspective, you could also say: “China doesn’t have a “eugenics taboo” and look at the consequences” (horrible one-child policy + forced sterilisations/ abortions + non-Han ethnic cleansing are seen as okay). You could also note that ‘extreme’ eugenic attitudes are incredibly common in China—people do care about the ‘superiority of the Chinese race’, and views regularly go way beyond those a more rational westerner would see as acceptable.

IIRC, China didn’t adopt the one-child policy based on traditional Chinese eugenics beliefs (优生 yousheng ). Rather, Deng Xiaoping’s advisors in the 1970s over-reacted to Western antinatalist, degrowth, eco-alarmist propaganda as promoted by Paul Ehrlich, the Club of Rome, and others. Then in the late 1970s they hired physicists untrained in demography to do simplistic models of China’s expected population growth, based on outdated, unreliable census data from the early 1960s. They panicked about Chinese ‘over-population’ because the West was panicking about ‘over-population’, and the one-child policy was the result. It was based only a little bit on Western or traditional Chinese eugenics; it was based mostly on eco-alarmism.

For more details on this strange story, see ‘Imperfect Conceptions’ by Frank Dikotter, and ‘Governing China’s population’ and ‘Just one child’ by Susan Greenhalgh

Yep, agreed (I haven’t read those books, but I broadly know the story). I wasn’t trying to imply that eugenics was the main cause of the one-child policy, but the two are definitely connected. Post-1CP, the state took a really active role in controlling how and when kids were born, compulsory sterilisation (mostly of females, despite vasectomies being safer) became normalised for ‘quality and quantity’ etc.

A stronger “eugenics taboo” could plausibly have limited the scope of the policy.

Fact updated: In recent days, China is encouraging young people to have more children, in order to fight population aging. It is now allowed to have 3 children per family. Despite the recent propaganda of having more children, lots of young people in China are not willing to have even one child because the higher education and/or marriage cost, and the birth rate keeps dropping.

This is not intended as a reply to the substance of your post but rather as a reply to your choice of vocabulary. I don’t understand why it is helpful to use the word “eugenics” to refer to modern assistive reproductive technology and/or human genetic engineering. Eugenics commonly refers to a primarily 20th century movement which was a force for tremendous evil.

Why try to repurpose that word when you could just choose a new one?

I briefly deal with this issue above, essentially saying that the term needs to be rehabilitated because it is already applied to many different phenomena/interventions and all of these fit the literal definition of eugenics. And I think the benefits of discussing eugenics openly outweigh the risks. What I didn’t get into is that terms like “reprogenetics” and “liberal eugenics” have really not been taken up.

Here is an excerpt from another piece I wrote on how common it is to label individual choices eugenics:

“While progressives maintain that abortion on the basis of disability is not eugenics, they have criticized many other individual choices as eugenics. For example, in 2019 George Church discussed his plans to make a genetic matchmaking app, digid8, which would prevent people with rare genetic diseases from meeting each other. This would diminish the risk of passing a disability onto their offspring (a similar approach to that used by Dor Yeshorim). This private company’s service—which people would have to opt into and pay for—caused huge controversy over its eugenic implications. Another individual choice, using genetic screening to choose an embryo to implant during invitro fertilization (IVF), is also widely associated with eugenics, especially if parents select for cosmetic features like eye color. If the individual choice of using a dating app or engaging in embryo selection is eugenics, certainly the individual choice to terminate a pregnancy on the basis of disability also fits this definition.”

I get that newer practices fall under the meaning of eugenics in Greek. But still, wouldn’t it be better to use a word that isn’t associated with the racist type of eugenics?

Is the idea to fully confront the arguments/controversies that come up over the “eugenic implications” of newer reproductive technologies?

“Is the idea to fully confront the arguments/controversies that come up over the “eugenic implications” of newer reproductive technologies?”

Yes, exactly. The advent of polygenic screening and the first people to use it to select embryos has brought this issue to the fore.

Very frustrating that an attempt to discuss the subject openly is getting so downvoted. I found it an interesting and well-researched read

This is the only thing I’d disagree with—if he’d knowingly broken a law and in so doing caused predictable and serious harm, throwing him into prison seems like pretty reasonable behaviour.

I see no reason someone should suffer and their family should suffer if instead there is a mutually agreed upon intervention that keeps the suffering from happening. To be fair, I don’t know if Patrick and Susan meant to have children (she’s cognitively disabled). But many people share your view. Men can be put in prison for not paying court ordered child support and reduced sentences or other incentives for men to get vasectomies are not allowed because of accusations of eugenics.

To me, offering Patrick an incentive to get a vasectomy seems analogous to giving an opiate addict methadone so they don’t steal money to buy opiates, rather than putting them in prison for stealing.

Maybe I misunderstood what happened. It sounds like they had 4 children, 3 of whom were disabled, and then the German state caught on and punished them? If so, this seems like callous enough behaviour to me that a strong form of retribution makes sense as a deterrent just as it would for crimes like manslaughter, even if we didn’t have reason to think they’d be repeated by the individual.

I’m surprised why this post is being downvoted. It takes a controversial topic but seems to talk reasonably through it?

(For those downvoting, maybe mention your reasons?)

I haven’t downvoted or read the post, but one explanation is the title “You’re probably a eugenicist” seems clickbaity and aimed at persuasion. It reads as ripe for plucking out of context by our critics. I immediately see it cited in the next major critique published in a major news org: “In upvoted posts on the EA forum, EAs argue they can have ‘reasonable’ conversations about eugenics.”

One idea for dealing with controversial ideas is to A. use a different word and or B. make it more boring. If the title read something like, “Most people favor selecting for valuable hereditary traits.” My pulse would quicken less upon reading.

Couldn’t agree more. I think clickbaity pulse-quickening titles are more forgivable for blog posts on a personal page (which this post originally was) than on the EA forum. I’d recommend that Sentientist modify the title they use for the crosspost to this forum.

I’m happy to modify the title to better fit the norms of EA forum. Can you (or anyone) suggest one here or in my messages?

Sure! I think “Most people endorse some form of ‘eugenics’” would fit EA forum norms better.

Done

I suspect that the social cost of making “I have [better/worse genetics] than this person” a widespread, politically relevant, and socially permissible subject outweighs the potential benefits of policies like subsidized abortions for people addicted to drugs and special incentives for educated women to have kids.

With regard to targeted abortion subsidies, what about the risk of reanimating the “abortion is eugenics” argument against its legality, particularly in the US, where abortion has been banned in many states? If you believe that abortion’s legality has had very positive genetic effects, then shouldn’t preserving that legality be an extremely high priority, and the political cost of proposing this policy prohibitive?

If you want to make abortions more accessible, why not make them free for everyone, making it a better option for people who might not be able to face the short-term financial burden of its cost, reducing the odds of it being banned by reinforcing the idea that it is is a right, and avoiding the backlash that a targeted subsidy would unleash?

It seems like ensuring that everyone gets to decide when they are best prepared to have and raise kids, if ever, has such incredibly high positive externalities that if anything there is a strong argument that abortion should be free already. The same goes for condoms, birth control pills, and IUDs.

Why not advocate for new, universal public goods, rather than policies that unnecessarily risk negative social and political impacts?

I didn’t advocate for any particular policy regarding abortion. And, I’m not reanimating the abortion is eugenics argument myself, Clarence Thomas and the prolife movement in America make this argument regularly. It’s just that progressives rarely come across it.

I completely agree with free contraception and giving people inexpensive reproductive autonomy. I’m in favor of legal abortion. But I know enough people who think abortion is morally abhorrent and a crime that it’s difficult for me to uncritically endorse legal abortion in places where pro life citizens are the majority.

I’m not sure I agree with free abortions for everyone. As I said in the piece, Israel subsidizes abortions for unmarried women and women whose children are likely to suffer disability. I don’t know if this targeted subsidy “implying it’s better for some people to have kids than others” has the kind of bad social effect that you are alluding to. From what I know of Israel, it seems not to.

The argument you are making is that abortion and free contraception will have eugenic effects anyway, so why not just give people full reproductive autonomy without nudging anyone in particular. I think this is a good argument.

It’s true that you didn’t technically advocate for it, but in context it’s implied that subsidies for abortion for people who are addicted to drug use would be a good policy to consider.

“We are not going to stop hearing about eugenics. Every time someone tries to call it something different, the “e” word and its association with historic injustice and abuse is invoked to end the discussion before it can begin.

When someone says that screening embryos for genetic diseases, giving educated women incentives to have children (like free child care for college educated women), or offering subsidized abortions for women addicted to drugs is “eugenics” they are absolutely using the term correctly.”

I accept that the idea “abortion is eugenics” is already advanced by some conservatives. However, I think that the policy of targeted abortion subsidies would convince more people that “abortion is eugenics,” and I think that this would make it easier to ban abortion.

I think the fact that Israel already has a very different cultural environment regarding genetic interventions means that those examples of targeted subsidies may well be much more controversial in other countries.

I’m glad you agree on that last point.

For me it’s been good to make a habit of looking for the least controversial policy that achieves desired goals. I often discover reasons that the more controversial options were actually less desirable in some way than the less controversial ones. This isn’t always the case, but in my experience it has been a definite pattern.

>Most people endorse some form of ‘eugenics’

No, they don’t. It is akin to saying “most people endorse some form of ‘communism’.” We can point to a lot of overlap between theoretical communism and values that most people endorse; this doesn’t mean that people endorse communism. That’s because communism covers a lot more stuff, including a lot of historical examples and some related atrocities. Eugenics similarly covers a lot of historical examples, including some atrocities (not only in fascist countries), and this is what the term means to most people—and hence, in practice, what the term means.

Many people endorse screening embryos for genetic abnormalities. The same people would respond angrily if you said they endorsed eugenics; the same way that people who endorse minimum wages would respond angrily if you said they endorsed communism. Eugenics is evil because it descriptively describes something evil; trying to force it into some other technical meaning is incorrect.

That seems pretty dis-analogous to me—while exact definitions vary, communism does have a fairly precise thing its referring to—the state or collective worker ownership of the means of production, abolition of free markets etc. Supporting a minimum wage doesn’t make someone a communist because 1) they probably don’t support the nationalisation of all industry and 2) many communist countries didn’t actually have a minimum wage. I think it’s fair to say that, all else equal, a minimum wage supporter is probably closer to the communist side of the spectrum than someone who opposes them, but they’re still a long way away.

Precisely. And supporting subsidized contraception is a long way away from both the formal definition of eugenics and its common understanding.

The first definition I get from google for ‘eugenics’ is

which seems like it includes a lot of the things described in this post that normal people support like incest avoidance and your example of embryo screening?

In contrast the first definition I get for ‘communism’ is very narrow and makes it clear that necessary components include things most people don’t believe (class war, public ownership):

In the current zeitgeist, and even for the past couple of decades, “that’s eugenics” has shut down conversations among intelligent people about important topics like behavioral genetics, reproductive technology and subsidized contraception. “Eugenicist” has been leveled against everyone from Darwin to EO Wilson, to Margaret Sanger, to Bill Gates to Nick Bostrom as a way of signaling that we should ignore everything that person has to say and see everything they do or think as evil and illegitimate. Communist or communism isn’t used in this way and communism doesn’t have this sting. Maybe during the McCarthy era an essay like this could have also been necessary.

And of course people respond angrily if called a eugenicist- it’s a term, as you said, that means “evil” in the current Western zeitgeist (but not in much of the rest of the world, as one commenter noted). This essay isn’t meant to be dispassionate, it’s meant to provoke the reader into rethinking how this term shuts down conversations about ideas and people.

I feel that saying “subsidized contraception is not eugenics” is rhetorically better and more accurate than this approach.

Saying “subsidized contraception is not eugenics” is a lie.

I argue that it’s entirely the truth, the way that the term is used and understood.

The second example here seems wildly different from most of the rest of the examples in the article. A eugenic justification for free college child care involves people being rewarded monetarily by the government, not for their behaviour, but for their perceived genetic superiority.

I think this reveals a bit of my problem with the article: it gives the strawman impression that the only reason to be opposed to nazi eugenics was the coercion and murder. But there were other reasons too, like the state rewarding and punishing people based purely on their unchangeable genetics and not on their actions, the view of disabled people as burdens on society, the obsession with racial differences, etc. If a policy resembles these negative effects, I think a (calm, reasoned) comparison to historical negative eugenics is warranted in the discussion.

Could someone please expand on the relevance of this post to EA? It is not clear to me how it contributes to the discussion around Bostrom nor what the “important means of improving the world” are.

Many EA ideas and proposals get called ‘eugenic’ by conservative commentators—especially those concerning transhumanism, cognitive enhancement, moral enhancement, mind/machine interfaces, etc. EAs might not be very aware of these criticism, since they mostly come from outside EA, and from political and religious views that few EAs share.

But IMHO we need to be able to challenge the term ‘eugenics’ as an all-purpose slander that gets thrown around against any proposals that involve nudging the direction of future human development.

The difference between eugenics and transhumanism is consent. eugenics cannot be rehabilitated; The word is irrevocably bound to refer to incredible consent violation, to the point where even calling it merely a consent violation dishonors the people who died at the hands of the Nazis. heal genetic diseases, don’t violate and murder people. do not commit eugenics.

The major problem with your post (and with eugenics) is that you assume desirable genetics are good genetics. In reality, there is no such thing as “good” genetics. Either you survive or you don’t, a person with many ailments can live longer and have more children than a conventionally fit person, because we live in a dynamic environment with volcanoes and staircases and murderers. The best genetics are a wide variety of genetics, because the environment is ever changing and what is good today may not be good in 10000 years, and if you breed out the “bad” genetics, you won’t have the tools available to deal with the changed environment.

Any kind of selection of partners should happen as unconsciously as possible. This is partly why most people fall in love with strangers and don’t select partners with the exact optimal genes. There is no dating app that matches you with your exactly optimal genetic partner (don’t get any ideas if you live in silicon valley), people don’t want that and it speaks to our innate desire to select a variety of genes rather than the “best” genes. Even though genes that happen to be good in the current environment tend to be more selected for, this happens naturally and unconsciously which is what separates it from eugenics. Eugenics always involves some authority deciding which genetics are good and bad and then organising social structures to enforce those categories. This is obviously wrong.

Mods: We should probably throw a Community tag on this.

If the alternative is being a disgenicist, a little knowledge of Greek looks quite definite to chose… :-)