Could Ukraine retake Crimea?

Why this question matters

The extent to which Ukraine needs to reinstate the prewar status quo before negotiating with Russia is a matter of dispute. On one side of the debate, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, has said Ukraine is only prepared to enter negotiations with Russia if its troops leave all parts of Ukraine, including Crimea and the eastern areas of the Donbas [1], and most of Ukraine’s western allies at least nominally agreed to support Ukraine until it is ready to negotiate [11]. However, others have argued that recapturing Crimea and the Donbas is unlikely to succeed [2 3 4], or that if it does succeed, the humiliation might lead Putin to use nuclear weapons [12].

If it is highly feasible for Ukraine to retake Crimea, then policymakers need to think long and hard about whether the increased bargaining power this would confer to Ukraine would be worth the increased risk of escalation. If it is totally infeasible, then this question is somewhat less urgent in the current crisis.

Similarly, I’d like to understand the role that certain types of military aid (e.g., ATACMs) that Ukraine has been asking for but hasn’t yet gotten might play in a potential retaking of Crimea or the strategic “land bridge.” If these things significantly increase Ukraine’s odds of attempting and/or succeeding in the retaking of Crimea, then we should update our estimated risk of nuclear war if / when the US provides them to Ukraine.

Below, I outline what I understand to be the basic components of the “most viable” scenario based on what I’ve read in foreign policy magazines, think tank publications, and the news. My non-expert take is that it would be pretty hard for Ukraine to successfully take back Crimea, and I’d love feedback on the scenario, as well as ways of formally modeling any or all of the hypothetical stages.

A potential scenario

My review of popular foreign policy analysis suggests that an attempted Ukrainian recapture of Crimea would take place in three stages:

Stage 1: Isolate Crimea

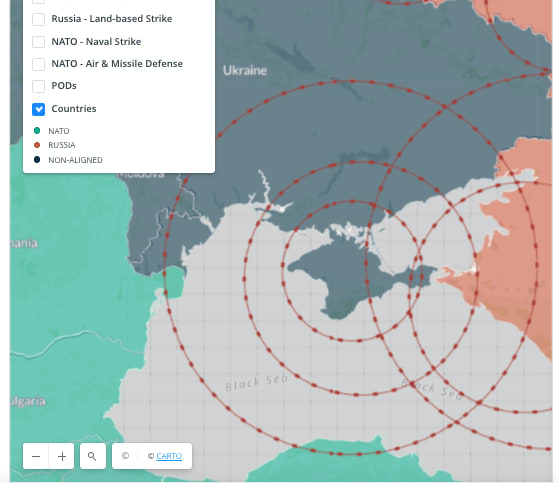

During this stage, Ukraine would sever Russian supply lines to Crimea via both the a) Kerch Bridge (which it would need to destroy, not just damage) and the “land bridge” that Russia still partially holds. [9]

The latter is seen as a possible outcome of the spring offensive, but they’d probably want to do so by working their way down from Kharkiv rather than via Zaporizhia because crossing the Dnipro near Zaporizhia could be hard given the Russian forces on the other side. [7]

There seems to be a lot of debate about how critical HIMARS will be. Some also argue that for Ukraine to actually be able to retake the land bridge, it would need [9]:

Longer-range capabilities such as ATACMs, a surface-to-surface missile that has a range of 190 miles, which Biden had said was not going to happen as of February 2023 [14].

Equipment to deploy a large armored force capable of penetrating enemy lines without getting blown up by mines or trapped in trenches (more tanks, armored vehicles, etc. than they already have.)

One skeptic I’ve spoken to (who has a pretty strong track record in campaign analysis) asked me, “If Ukraine were to succeed at all of this, couldn’t Russia just supply Crimea using naval forces in the Sea of Azov?” and I haven’t yet adequately explored that possibility.

Stage 2: Get Ukrainian troops into Crimea

There are essentially two ways for this to happen.

First, Ukrainian troops could cross the Syvash. Also known as the “Putrid Sea,” Syvash is a collection of shallow lagoons that were crossed twice at low tide during WWII. To do this, Ukraine would need to use artillery on the far shore for core, then go across the lagoon in boats and establish a beachhead and push onto the interior [5]. They would also need to disable Russian warships, which could be done by a waterborne drone strike like the one that sank the Moskva in November 2022 [6]. I haven’t yet found much on what Ukraine would need to do to disable Russia’s shoreline defenses, but that seems like a nontrivial component. Another challenge to this approach is that Ukraine would probably need to requisition civilian boats to get enough personnel and equipment across Syvash.

The other option is for Ukrainian troops to do a land crossing via the Isthmus of Perekop. Michael Kofman told DefenseOne that Ukraine could somehow clear the way for this with a barrage of GMLRS rockets, but he remained skeptical of the feasibility [5]. Intuitively, it seems like Perekop is so narrow that troops crossing there would be easy targets of Russian forces.

Stage 3: Re-capture and Hold Crimea

Once the Ukrainians got ground troops across the Syvash Lagoon or across the Isthmus of Perekop, they would still need to set up a beachhead, and then take and hold Crimea, which would be a challenge due to the trenches, mines, and anti-access/area denial weapons in Crimea (see below). Additionally, Russian long-range capabilities could hit them from the Caspian Sea, Black Sea Fleet, or even inside of Russia according to Neil Melvin at RUSI [9].

How could we model this potential conflict more accurately?

Ukraine’s imminent spring offensive is likely to include some form of stage 1, so I’m not sure if it’s worth trying to model at the moment as opposed to just monitoring what happens. Instead, I’ve been looking at various military campaign analysis models that might be able to capture stage 2 or 3 of this hypothetical scenario. So far, I’ve looked at Lanchester Models, Salvo Models, [15] and an input distribution version of the Attrition-FEBA model [15, 16]. I don’t yet have a strong opinion about what would work the best, but I don’t think that Attrition-FEBA allows for ground and air support to be integrated together. The more complex models that account for the heterogeneity of forces seem to be too unwieldy to be feasible given data limitations and given the huge number of assumptions that I’d be making to model this, I think that erring on the side of simplicity would be best.

Additional Notes

Pardon the out-of-order citations. I created this post based on an ever-growing Google doc, and haven’t had time to polish things, as I’m still not entirely certain of how useful this line of inquiry is for a civilian.

Military guy here. Things that we always consider are the most likely course of action and the most deadly course of action that the adversary can take.

Since this is a trench warfare with the added emphasis of drones, the most likely course of action is that things won’t change much and that battle lines will remain stagnant. This is with the additional point of contention that Ukraine right now is going through the most incredible logistical supply chain process that has ever happened, and Russia kinda keeps losing generals due to stupid OPSEC losses. Of course there will be a spring offensive and counter offensive, and I would favor Ukraine in this manner because it’s their territory, etc, and a point of national pride.

The other problem is the enemys most deadly course of action which is to launch CBRN type weapons back at the Ukrainians. Russians have been entrenched in Crimea for years so getting them out of that position is going to be difficult. They have time to mine and booby trap everything. However… the dark horse that is nuclear usage really needs to be understood from the lens that (A) someone has to accurately tell Putin what is going on (B) he has to respond requesting this to happen (C) someone has to launch a nuke (and the doctrine is that nukes are kept at the Battalion level in the Russian Army) (D) all of this has to not be stopped somehow by an intelligence leak or an insider who doesn’t want a nuclear war.

Yeah, it seems like even if it’s possible to take back Crimea with conventional weapons, there’s an extremely high chance of a Russian retaliation or denial strategy that features tactical nukes or something else. We can hope that there’s a Stanislav Petrov 2.0 in the ranks somewhere I guess...

Do you have a strong sense of which weapons systems, drones, etc. would be most decisive on the conventional front? Other than the few that I’ve mentioned in the post, I’m still pretty naive to what’s important here.

Artillery is the biggest conventional threat. Indirect fire, combined with drones or better spotting would lead to the largest amount of casualties.

This is unconventional(Information Operations), but I would expect that the better question is what are the fighters willing to accept? If they’re getting shelled everyday with more and more accurate artillery rounds that is going to eat away at whatever morale they have left. It’s far easier to walk away from a war in which you’re guaranteed certain death and go AWOL than to stick around as people around you are whittled down. Ukrainian fighters seem to be all in regarding this, as they have stood against Russian artillery the whole time. Russian fighters? I get the sense that they’re not as well informed as they should be. Information seems to be siloed off differently(and this is just from following the news), as I wouldn’t -if I were a dictator- want the real truth of the matter to reach a demoralized front line, months after they were supposed to be in a short decision mission.