Should You Have Children Despite Climate Change?

Background information

This is the script of what would’ve been A Happier World’s video on climate change if Kurzgesagt hadn’t published theirs. The main ideas we wanted to convey were:

Climate change is important but the doomerism is overstated

The best actions you can take are participating in political activism and donating to effective charities

The question whether or not to have children despite of climate change was just our way of framing the video to promote these two ideas. And since (1) has been covered by Kurzgesagt and (2) in our response video, we decided it doesn’t make that much sense anymore to create a video on the question of having children. Instead, it seemed a low effort with potential positive impact to publish this script on the EA forum instead. Note that there could still be a few mistakes, since we never got to entirely finalizing it.

Should You Have Children Despite of Climate Change?

Intro

In october 2020, the then 33-year old swiss national Marc Fehr got a vasectomy.** The reason? He wants to save mankind from extinction. Fewer offspring means fewer emissions, the argument goes. He’s not alone in this reasoning.

Even Prince Harry has said he doesn’t want more than two children because of climate change.*

Miley Cyrus doesn’t want to bring children on this “piece-of-shit” planet.* British front woman Blythe Pepino gave up on the idea of having a family after listening to a lecture by Extinction Rebellion, and then started a movement of women not procreating in response to the coming ‘climate breakdown and civilisation collapse’.* And even David Attenborough has stated several times that we need fewer people on this planet in order to solve our environmental problems.*

A poll last year found that 39% of young people “feel uncertain” about having children because of climate change.** The main reasons are that they’re scared of the future their offspring will face, and that having children could contribute to even more climate change.

Climate change is definitely bad. There’s no doubt about it. Many animal species are at risk of extinction, natural disasters significantly worsen the lives of a lot of people especially in the southern hemisphere, but increasingly also affect the population in western countries.

But how bad will our future exactly be, and will having children really make things worse? What are the best actions we can take to help the climate?

Will the future really be that bad?

When climate activists or politicians talk about climate change, their rhetoric tends to be very drastic, sometimes even apocalyptic. Many claim we have less than a decade left to save the planet.

Johannes Ackva: I think where this idea comes from, is from IPCC report that says if we want to hit the 1.5 degree target, we need to reduce emissions by 50 percent over this decade. This is very different from saving the planet, which is very, very underspecified to begin with. But it’s not that we either reach 1.5 degree or the world ends.

The IPCC is an internationally accepted authority on climate change, and its work is widely agreed upon by leading climate scientists as well as governments. We’re currently at 1.1 degrees celcius of warming* compared to the average temperature between 1850 and 1900.

Maarten Boudry: Climate change is a problem that will get worse and worse. And we have agreed on some artificial thresholds that we don’t want to cross, but that’s partly arbitrary. It’s not as if there’s a specific moment in time when suddenly all hell will break loose. I think we should be aiming for as little warming as realistically possible. Two degrees is worse than one degree, three degrees is worse than two degrees, etc.. But the idea that we only have a couple of years to save the planet and then after that time everything is lost is, I think, a really bad notion to push.

John Halstead: So it’s not the case that doom is around the corner, but it is still bad and it’s bad especially for the world’s poorest people. If you look at agricultural impacts, it’s quite bad for countries in the tropics, but in higher latitudes like in Europe and China and in the US, it’s—the effects on agriculture are projected to be quite mild. And I think that picture is confirmed for lots of other impacts that climate change might have like heat stress and things like that.

What exactly will happen?

Let’s go over what we can expect with an increase in global warming, according to the IPCC and other sources. Note that one degree celsius of global temperature increase doesn’t mean a flat increase across the whole globe. Some regions will have higher temperatures than others. Some places might experience a 2 degree increase in average temperature, other places might have a 7 degree increase. Especially landlocked regions and regions closer to the arctic will see the highest increases. For example, while the global average is currently at 1.1 degrees, Switzerland is already at 2 degrees.*

With increasing global warming, we can expect more feedback loops resulting from ice melting, permafrost melting, trees dying and more.*

Luckily, most known feedback effects seem to be relatively minor compared to direct temperature increases due to anthropogenic emissions.*

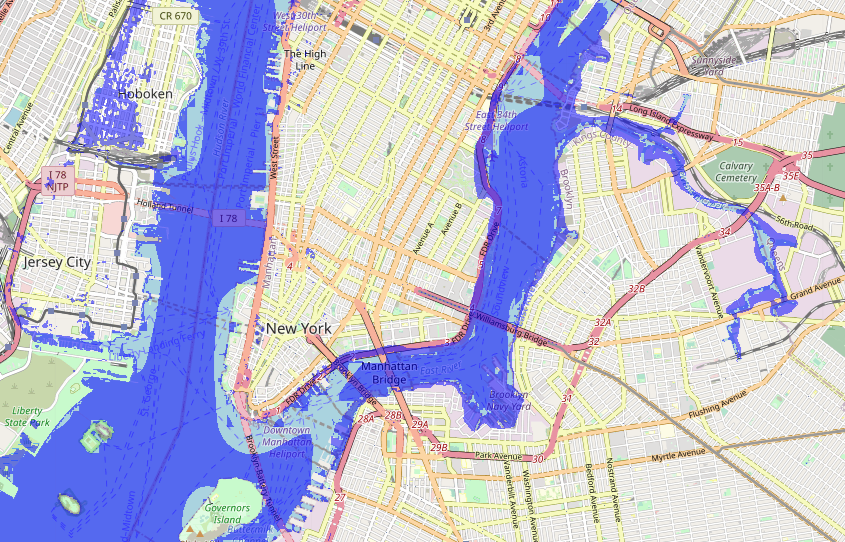

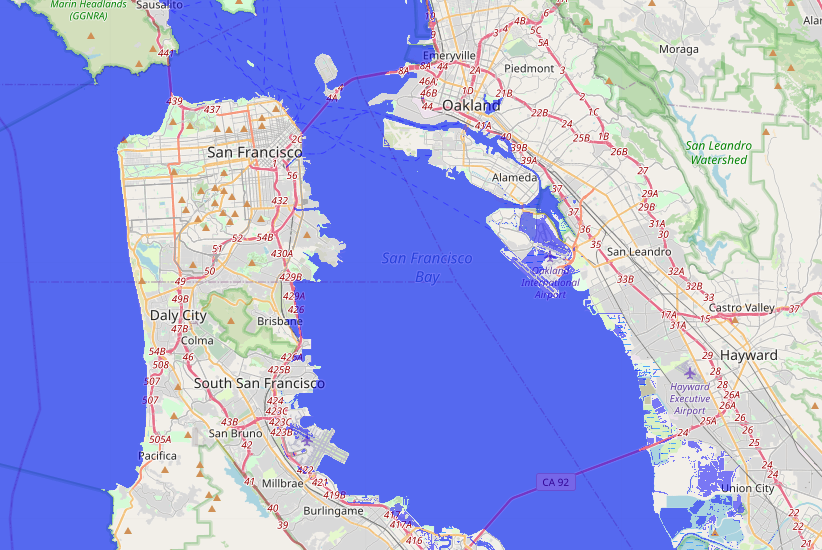

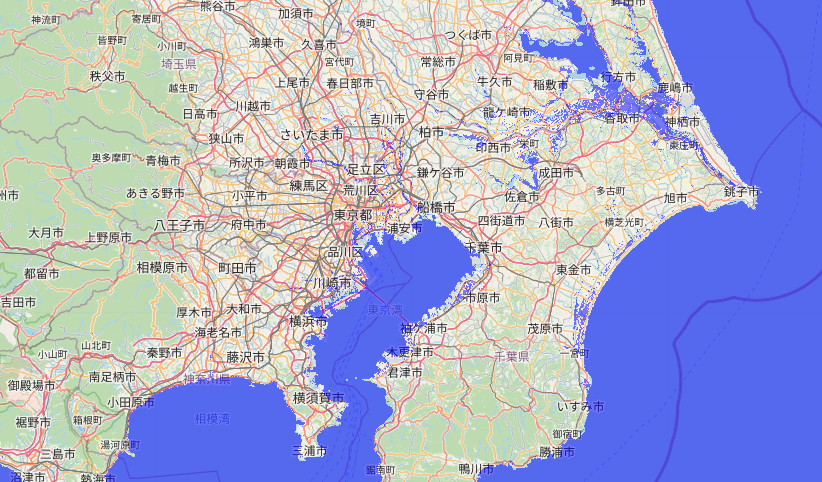

The median expected sea level increase by 2100 is another 30 centimetres, 1 metre in a worst case scenario****. 1 metre would look like this in the following places:

But by then, we’ll very likely build floodwalls and dunes to prevent most of this.

1.5 degrees

If we reach a 1.5 degree increase by 2100, there will be a four-fold increase in extreme events.* In the arctic, ice-free septembers will start to occur.* Permafrost, ground that is normally frozen for 2 years or more, will start to abruptly thaw, freeing up methane in the atmosphere that will increase emissions by a lot.*

3 degrees

At 3 degrees, there will be a five-fold increase in extreme events.* In the arctic, ice-free septembers will be permanent.* There will be sufficient warming to lead to the eventual loss of most glaciers outside the polar regions. Over 18% of species on land will be at high risk of extinction. In Europe, the number of people at risk of heat stress will increase two- to three-fold compared to warming levels of 1.5°C. Billions of people are projected to experience chronic water scarcity due to droughts.****

4 degrees

At 4 degrees of warming half of all animal and plant species will be at high risk of extinction.*

5+ degrees

At 5 degrees and higher it’s really difficult what to predict, the IPCC report barely makes any mention of it. 6 degrees celcius gets mentioned only once in the full 3675 page report.* We can be sure 6 degrees would be extremely awful, likely causing mass extinctions. Advanced civilization could be threatened, but humanity would likely still survive since species in the past have survived even higher temperature increases.***

So what’s the most likely temperature we’ll end up with?

Johannes Ackva: I think if you look at the literature right now, that’s trying to extrapolate from current trends, the most likely futures are in the 2.5 to 3.5 degree range. Of course, those kind of estimates always kind of extrapolate based on what we’ve seen so far. So they underestimate fundamental changes that could happen. For example, they’re probably conservative as you could see transformative technological changes and you end up in a much lower warming world. You could also, I think, something that feels very acute right now, observe a change in global geopolitical conditions that lead to more warming. But from everything that we know right now, I think the most likely range would be in that 2.5 to 3.5 degree range.

John Halstead: On current policy, it looks like there’s something like a one in 20 chance of four degrees of warming, which would definitely be bad. But also it’s very, very far from an extinction level thing.

Johannes Ackva: I think the odds for six degrees based on the current trajectory is probably less than one percent. So I just looked at data on this, which was actually from 2017. Extrapolating this from 2017 data where six degrees was about a percent. And since then the most extreme emission trajectories have become less likely. So it’s probably less than one percent for sure.

Climate change could be horrible, depending on how we deal with it in the coming decades. Especially for poorer countries it will be awful. So we need to act urgently to solve it. But it won’t be world-ending bad.

What does this mean for having children?

So what does this all mean though for the decision to have children in light of climate change? What kind of world would our children be born into—could the effects of climate change still be bad enough?

Jeroen Willems: Do you have any children?

Johannes Ackva: I don’t have any children.

John Halstead: I have—I have one daughter. Yeah.

Maarten Boudry: I don’t have any children, but that’s not an ideological decision. It’s just that in my life at this point, I feel like I’d rather not have children.

Jeroen Willems: And what would you say to people on the fence about having children because of climate change?

John Halstead: I think that the world is not going to be so bad that your child is going to have a negative life. That’s especially true if you’re in a rich liberal democracy in Europe or America. It’s just—the effects just aren’t big enough to kind of create a hellscape that your child might live in.

Johannes Ackva: Climate change is a serious problem. But based on the progress we have already made, it’s very unlikely that it’s an end of the world style problem that makes life not worth living anymore. Especially if you’re in a high income country. I think the reason to care about climate change from a humanitarian perspective are vulnerable populations in emerging economies or in developing economies. It’s not that life in a rich country is going to be unbearable in the 2050s because of climate change.

Maarten Boudry: I think even if you take into account climate change, there’s probably no better time to be alive and even to be born than today in 2022. 50 years ago we also had problems. There were also people who were afraid of having children because of the hole in the ozone layer, because of acid rain, because of pollution. There was also this general sentiment that the world was going to end and that there was going to be overshoot and collapse. Things looked pretty bleak 20 or 50 years ago as well, and we also managed to find solutions to these problems.

So our children probably won’t live in a much worse world than we do—and in light of recent progress in many areas like poverty alleviation and technological advances it will hopefully even be a better world.

But maybe you’re considering not having children because of the negative effect your offspring might have on climate change?

Children’s (and our personal) effect on the climate

Many people think of overpopulation as a potential problem. Others might think their children and grandchildren will emit a lot of CO2, which they believe would hurt the planet too much. So what are the facts?

Maarten Boudry: I think this idea of just having fewer children ironically also underestimates the magnitude of the challenge again. We don’t just have to lower our emissions a little bit. We have to bring them all the way down to zero. The really effective solution is to find ways of generating energy and all the other services that fossil fuels provide without greenhouse gas emissions. And once you have that solution, then it doesn’t really matter how many children you have on this planet or for that matter what your level of affluence is. So I think this idea that we need to lower consumption or that we need to lower the birth rate is really a counterproductive way to go about solving this problem.

Johannes Ackva: So if you’re in a high income country, your annual emissions right now are something like maybe 10 tonnes a year. And already by the political and economic changes that we’ve seen in high income countries, this share is going to go down.

John Halstead: I think it’s just a skewed way of looking at the effects that people have on the world. Like it’s true that your child would release CO2, but they would also have lots of other positive effects. You know, they might make the world better by setting up a really valuable business or working for a charity or donating or engaging in political activism. And so there’s lots of reasons to think that, you know, the world gets better even as population increases, since for the last 200 years, the population has exploded, but people have also got a lot better off. So if you think that process is going to continue, then that’s a reason to have more children.

Johannes Ackva: I think if you’re so concerned about climate change that you’re considering not having children, your children will probably be great environmentalists.

What can we do about the climate?

(A lot of this is basically copied from our response video to Kurzgesagt, since it was an improved version of the original script)

If staying childless or other lifestyle changes aren’t the ultimate solution to save the climate, what can we actually do about the very real climate challenges the world is facing? First of all, most of the impact isn’t going to happen because of individual actions. A lot of things need to happen on the political side! Governments have a huge impact on future emissions. And we need to make sure countries don’t only look at their own emissions, but at how they can impact emissions globally.

Johannes Ackva: I think one interesting example for this is the success of solar, which has been driven by countries like Germany for example, which has almost not reduced emissions in Germany itself. You can really kind of ignore it in the grand scheme of things. But it had transformative effects globally speaking. That’s an example where the global effect is much, much larger than the local effect. And those are the examples that we have to repeat to really make a dent in global emissions.

All of this doesn’t mean that there’s nothing individuals can do to combat climate change. But the impact we as individuals can have has little to do with changing our lifestyles.

Johannes Ackva: So I would say the most important thing that you can do as an individual in a high income country is political engagement. This can be both direct political activism, asking for a better climate policy or putting more pressure, and it can also be a donation. So donations as a kind of political tool through highly effective climate charities to reduce emissions. And both of these are going to have much more impact than changing your lifestyle. Because changing your lifestyle can at most reduce emissions by something like five tonnes a year, which is nothing in the kind of shape of things.

For perspective, Europeans emit roughly around 7 tonnes of CO2 per person and Americans 15 tonnes.* Kurzgesagt talks in greater depth about political activism in their video called Can YOU Fix Climate Change?.

Johannes works for Founders Pledge, an organisation that inspires entrepreneurs to make a commitment to donate a portion of their personal proceeds to charity when they sell their business. Founders, co-founders and CEOs of various companies have made this commitment.*

They have a dedicated team that does in-depth research on charities that have the biggest impact per dollar donated. Johannes is their leading climate scientist and he has researched multiple climate organisations.

So which ones are actually effective? Which ones give you the most bang for your buck?

The top recommendation of Founders Pledge is the US organisation Clean Air Task Force which aims to influence policy makers. They advocate for clean air measures and innovation in neglected low-carbon technologies. They mostly focus on US policy, but recently started advocating in other parts of the world too. Much of their clean air work includes advocating for regulations of fossil fuel emitting infrastructure and advising on methane regulation development.*

A rough conservative estimate of the cost of avoiding one tonne of CO2 by donating to the Clean Air Task Force is just one dollar.*** Remember, Europeans emit roughly around 7 tonnes of CO2 per person and Americans 15 tonnes.*

Johannes’ team at Founders Pledge estimates that the charity Carbon180 is similarly effective. They focus on ways to suck carbon out of the atmosphere, a process known as carbon capture and storage.*

TerraPraxis, another recommended charity, researches and advocates for more energy innovation. They focus particularly on advanced nuclear energy. New nuclear reactors will be much safer and potentially cheaper than already existing ones.* They are already quite safe, and just like wind and solar emit little to no greenhouse gases.**

Since the end of 2021, Founders Pledge also recommends a rather young and European charity: Future Cleantech Architects is a climate thinktank from Germany which advocates for clean climate technologies and aims to inform european policy makers about how to decarbonize sectors like cement or steel.*

Instead of choosing to donate to these charities separately, you can also choose to donate to Founders Pledge their climate fund. You don’t need to be an entrepreneur for this or commit to anything. Most of the money in the past has gone to the Clean Air Task Force.* But they always stay on top on the latest research so your dollar can do the most good.

Of course there’s a ton of climate NGOs worldwide. So if you’re professionally in a position to do so, you can also try and research further organisations which work on the best ways to help the climate!

Unfortunately right now there are a lot of organisations and popular actions that are immensely popular without having as big an impact. For example, planting trees or other carbon offsetting measures aren’t really effective in comparison. Offsets are always about direct interventions, whereas the world as a whole is spending hundreds of billions on climate and this is spending that can be changed by advocacy. Currently the allocation of these billions is not optimal, leaving vast rooms for impact for charities that move the needle so that government budgets are spent more in line with global decarbonization priorities.*

Conclusion

Of course we’re not pushing you to have children if you don’t want to, that’s not what this video is about. It’s a personal choice that is entirely up to you. Our main goal with this video was to paint a realistic picture of the climate’s future and to showcase what the best ways are to have an impact.

There are plenty of reasons to be cautiously optimistic when it comes to the future of our planet. Technologies like solar panels, wind power or battery development for electric cars have already led to major transformations in their respective industries. Plenty of other promising technologies need way more money and support from policymakers to get off the ground and transform industries like the cement industry or carbon capture and storage. But it is possible.

John Halstead: I would say I’m generally quite optimistic now. And there’s now more room for optimism in the last 10 years than there has been for many, many decades. Mainly because of progress in key low carbon technologies like solar, wind and batteries. And my one worry is that we won’t be able to continue that progress in other sectors, like how do we decarbonize steel and aviation and cement and things like that? But I definitely think we do have more cause for optimism and we shouldn’t despair as much as many people think.

I mentioned this in the ACX post on this too, but:

In my opinion, the strongest moral reason to not have children (for ~ any cause area, up to and including for pronatalism) is that the resources can be better spent elsewhere.

The strongest reason to have children is because you or your partner would personally be happier or more productive if you had children. The second strongest reason is if you think childrearing is actually the most cost-effective thing for you to do on the margin because of the effects of the children themselves, but at least for me, on the current margin, the burden of proof should be against.

I don’t have a confident view on this, but I can easily imagine situations where all your (grand)children have a bigger impact on the world than you alone. It might make sense for people to try and make their own EV calculations here.

I think that it is very difficult to beat community building (even non-professionally, just in some spare time) by having children. There is also an exponential growth in the effect, and probably with a greater growth factor. Moreover, the similarity between you and your grandchildren is probably not that important, and it is very plausible to me that their effectiveness decreases sufficiently quickly so that it doesn’t even beat direct effects that you could have instead.

This is also my view, and I think it applies on basically all consequentialist views, including even strong negative utilitarian views that you might have expected to endorse antinatalism.

I definitely agree about implications re: children. Scott Alexander also wrote what I think is a very sensible piece on the topic:

https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/please-dont-give-up-on-having-kids?s=r

Tyler Cowen believes you should have more children in order to combat climate change...

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-03-14/want-to-help-fight-climate-change-have-more-children

A thought: Especially when enabled by technology, people are very capable. In theory, a person can easily offset the negative impact of their greenhouse gas emissions and have a lot of time and resouces left over to pursue positive impact. For example, by donating a fraction of their money to carbon offsetting projects and not having a polluting lifestyle, the median American can easily have a net reducing effect on global greenhouse gas emissions throughout their lifetime. Also, I think the median person in the world can in theory achieve a net reducing effect as well, by devoting a fraction of their time and resources to planting trees (nature’s baseline technology for carbon capture).

So perhaps the right framing isn’t “Should you have children despite climate change?” One alternative framing is: suppose you want to influence the next generation, who will either capably help the world or capably harm the world. Should you do it by parenting and influencing your own children, or by influencing other people’s children?

I think most EAs favor the latter option, and indeed there is a compelling argument in favor of it. Humans are perhaps the only species whose primary mode of phenotypic inheritance is learning knowledge and values from group members: including not only parents, but also a lot of other people. This is why we are so adaptable and capable.

But for EAs who derive a lot of pleasure from parenting and are high-fidelity influencers as parents (i.e., have a high guarantee of influencing their children to have similar values as them), I think parenting can be an excellent use of their time and resources. I think optimal parenting is a domain which is quite neglected by EAs, and hope that this changes moving forward.

You might find posts with the parenting tag helpful.

Thank you so much for this extremely helpful suggestion, Linch! I really appreciate it.

I agree with previous posters: the primary reason to not have kids is that the resources are better spent elsewhere. I personally think my time is much more effectively spent directly addressing the world’s problems than raising kids that, 30 years from now, might make an impact. Because hey, it’s likely my kids wouldn’t be as brilliant as me, you know? (half kidding)

Also, what about the other many negative impacts of humans besides carbon emissions? E.g. microplastics, destruction of the natural environment for resources, pollution (it might be better than 50 years ago, but it’s far from being completely solved, right?)