Forget replaceability? (for ~community projects)

tl;dr:

I’m interested in questions of resource allocation within the community of people trying seriously to do good with their resources. The cleanest case is donor behaviour, and I’ll focus on that, but I think it’s relevant for thinking about other resources too (saliently, allocation of talent between projects, or for people considering whether to earn to give). I’m particularly interested to identify allocation/coordination mechanisms which result in globally good outcomes.

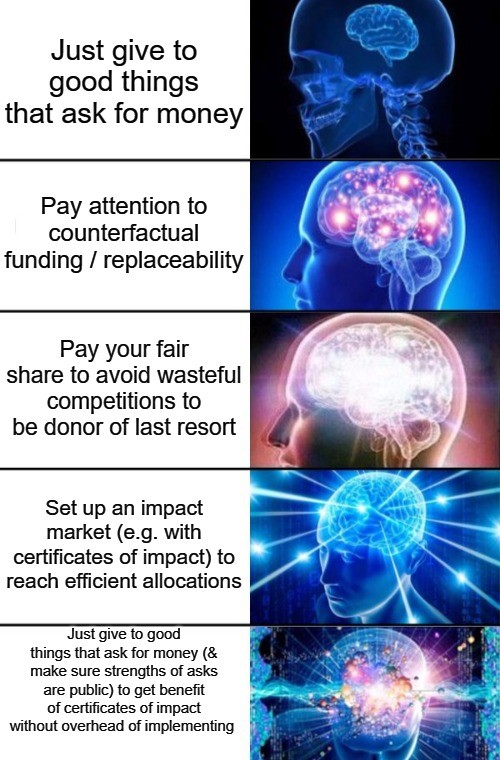

Starting point: “just give to good things” view

I think from a kind of commonsense perspective, just trying to find things that are doing good things and giving them resources is a reasonable strategy. You should probably be a bit responsive to how desperately they seem to need money.

The ideas of “effective altruism” might change your conception of what “doing good things” means (e.g. perhaps you now assess this in terms of how much they do per dollar spent, if you weren’t doing that already).

Replaceability considerations

If you care about counterfactual effects of your actions, it looks like it makes sense to think about what will happen if you don’t put resources in. After all, if something will get funded anyway, then your counterfactual contribution can’t be that large?

I think this is an important insight, but it’s only clean to consider when you model the rest of the world as unresponsive to your actions.

Coordination issues — donors of last resort

Say you have two donors who agree that Org X can make excellent use of money, but disagree about whether Org Y or Org Z is the next best use of funds. Each donor would prefer that the other fills X’s funding gap, so that marginal funds go to the place that seems better to them. If the donors are each trying to maximise their counterfactual impact (as estimated by them), they might end up entering into a game of chicken where each tries to precommit to not funding X in order to get the other to fund it. This is potentially costly in time/attention to both donors, as well as to X (and carries a risk that X fails to fill all of its funding needs as the donors engage in costly signalling that they’re prepared to let that happen).

A simple patch to this would be to have norms where the donors work out their fair shares of X’s costs, and each pay that. (But working out who the relevant pool of possible donors is, and what fair shares really look like given varying empirical views, is quite complicated.)

Impact markets

Coordination issues such as the above (see the comments for another example coordination issue) are handled fairly gracefully in the for-profit world. The investors who are most excited about them give them money (and prefer that they are the ones to give money, since they get a stake for their investment, rather than holding out and hoping that other investors will cough up). And orgs can attract employees who would add a lot of value by offering great compensation.

I’ve been excited about the possibility of getting some of these benefits via some explicit mechanism for explicit credit assignation. Certificates of impact are the best known proposal for this, although they aren’t strictly necessary.

What would a world with some kind of impact markets look like, anyway? At least insofar as it relates to allocation of resources to projects, I think that it would involve people being excited to fill funding gaps if they were being offered a decent rate by the projects in question. Projects above some absolute bar of “worth funding” could get the resources they needed, so long as the people running them were willing to offer a large enough slice of their impact. It would be higher prestige for project founders to hold onto a larger share of their impact, as this would imply a higher valuation.

People considering what jobs to take would look at the impact equity they were being offered for each role. People with good ideas might often try to turn them into startups, as the payoff for success would be high. People who had invested early in successful projects might become something like professional VCs, and build up more capital to invest in new things.

Implicit impact markets without infrastructure

There are some downsides to setting up explicit markets. They might be weird; they might be high overhead to run; and there might be issues we don’t notice until we try to implement them at scale.

So if we’ve identified the type of social behaviour that we’d like to achieve via markets, why don’t we just aim at that behaviour directly? We have the usual tools for creating social norms (creating common knowledge, praising the desired behaviour, etc.). I think this could work decently well, particularly as the recommended behaviour would be close to a commonsense position.

What would the recommendations actually be? There’s a certain audience to whom you can say “just imagine there was a (crude) market in impact certificates, and take the actions you guess you’d take there”, but I don’t think that’s the most easily digested advice. I guess the key points are:

For projects which are drawing their support from communities of people making a serious attempt to good in the world, feel free not to worry about the counterfactuals if you don’t commit resources

There’s a question about where to draw the boundary

I think because the suggested behaviour ends up tracking common sense reasonably well, we can be reasonably generous, not just a niche audience who’s read a particular blog post; but of course it’s still worth thinking about counterfactuals/replaceability for contributions which aren’t even engaged in the pursuit of having a big difference

Instead be attentive/responsive to how strongly projects are asking for resources, but only if the asks are made publicly (or it is publicly confirmed how strong they are)

If we’re going to be responsive to bids of desperation, we need some way to keep them honest, and not create incentives to systematically overstate need

As an extreme example, it would obviously be bad if a project founder was telling each of their dozen staff that their personal contributions were absolutely critical, such that they each imagined that they were personally credited with the majority of the impact from the project

Even if that were the true counterfactual in each case, it could easily lead to everyone staying working on the project when it would be better for the entire project to fold and release them to do other things

A proper impact market would get this because it wouldn’t be possible to assign more than 100% of the credit from a given project

Asking that the strength of asks be made public is a way of trying to create that honesty

“Strength of asks” could be made public in purely qualitative terms

They could also be specified numerically, as in explicit credit allocation, e.g. “if we raise our $1M budget, we think that 40% of our impact this year will be attributable to our donors”

I think this seems achievable for asks for funding; it’s more complicated for asks to individuals to join projects, as there might be privacy reasons to not make the strengths of asks public (similar to the fact that compensation figures are often treated as sensitive)

Really “public” isn’t what’s needed so much as “way to verify that promised credit isn’t adding up to more than 100%”

You could bring a trusted third party in to verify things; it feels like there could also be a simple software solution (so long as everything has been made quantitative)

It can still make sense to pay some attention to the general funding situation and possible counterfactuals, as that situation can give independent data points on how strong the ask really is / should be

e.g. if an org has a long funding runway already, then it should have a hard time making strong asks for money, and we should be a bit suspicious if it seems like it is

Socially, give more credit to people who have stepped in to fill strong needs, and less credit to the people making strong asks

And the converse: give more credit to people when they make it explicit that their asks are unusually weak (and a bit less credit to people filling such needs)

Take founding valuable projects (or providing seed funding for things that turn out well but were having difficulty finding funding) as particularly praiseworthy

How good would this be? It seems to me like it would very likely be better than the status quo (perhaps not that much better, as it’s not that dissimilar). I don’t know how it would compare to a fully explicit impact market. It’s compatible with gradually making things more explicit, though, so it might provide a helpful foundation to enable some local experimentation with more explicit structures.

Acknowledgements: Conversations with lots of people over the last few years have fed into my understanding of these issues; especially Paul Christiano, Nick Beckstead, and Toby Ord. The basic idea of trying to get the benefits of impact markets without explicit markets came out of a conversation with Holden Karnofsky.

- 's comment on [Linkpost] An update from Good Ventures by (17 Jun 2024 17:04 UTC; 87 points)

- 's comment on JP Addison’s Quick takes by (9 Apr 2024 15:39 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on How much funging is there with donations to different EA animal charities? by (14 May 2023 10:05 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Critique of the notion that impact follows a power-law distribution by (14 Mar 2024 14:54 UTC; 4 points)

Default expectations of credit

Maybe we should try to set default expectations of how much credit for a project goes to different contributors? With the idea that not commenting is a tacit endorsement that the true credit split is probably in that ballpark (or at least that others can reasonably read it that way).

One simple suggestion might be four equal parts credits: to founding/establishing the org and setting it in a good direction (including early funders and staff); to current org leadership; to current org staff; to current funders. I do expect substantial deviation from that in particular cases, but it’s not obvious to me that any of the buckets is systematically too big or too small, so maybe it’s reasonable as a starting point?

Inefficiencies from inconsistent estimates of value

Broadening from just considering donations, there’s a worry that the community as a whole might be able to coordinate to get better outcomes than we’re currently managing. For instance opinions about the value of earning to give vary quite a bit; here’s a sketch to show how that can go wrong:

This doesn’t quite fit in the hierarchy of approaches to donor coordination, but it is one of the issues that fully explicit impact markets should be able to help resolve. How much would implicit impact markets help? Maybe if they were totally implicit and “strengths of ask” were always made qualitatively rather than quantitatively it wouldn’t help so much (since everyone would understand “strength” relative to what they think of as normal for the importance of money or direct work, and Alice and Beth have different estimates of that ‘normal’). But if a fraction of projects move to providing quantitative estimates (while still not including any formal explicit market mechanisms), that might be enough to relieve the inefficiencies.

In my mind, a significant benefit of impact certificates is that they can feel motivating:

The huge uncertainty about the long-run effects of our actions is a common struggle of community builders and longtermists. Earning to give or working on near-term issues (e.g., corporate farm animal welfare campaigns, or AMF donations) tends to come with a much stronger sense of moral urgency, tighter feedback loops, and a much clearer sense of accomplishment if you actually managed to do something important: 1 million hens are spared from battery cages in country X! You saved 10 lives from malaria in developing countries!

In comparison, the best a longtermist can ever wish for, is “these five people – who I think have good judgment – said something vaguely positive at an event, so I’m probably doing okay”. Even though I buy the empirical and philosophical arguments for EA meta work or longtermism, I personally often find the dearth of costly signals of success somewhat demotivating, and I think others feel similar.

I think impact certificates could fix this issue to some degree, as they do provide such a costly signal.

I also wonder if a lot of people aren’t quitting ETG and doing direct work because they don’t realize just how valuable people would find their work if they did. If they’re currently earning $500k per year and donating half that amount, it feels kind of a downgrade to do direct work for $80k per year and some vague, fuzzy notion of longtermist impact. But if I could offer them a compensation package that includes impact certificates that plausibly have an EV of millions of dollars, the impact difference would become more palpable.

Edit: The “Implicit impact markets without infrastructure” equivalent of this would be to tell people what amount of donations you’d be willing to forego in return for their work. But this is not a costly signal, and thus less credible, and (in my view) also less motivating. Also, people across the EA community are operating with wildly different numbers (e.g., I’ve read that Rohin trades his time for money at a ~10x lower rate than I do, and I think he’s probably adding a lot more value than I am, so collectively we have to be wrong by >10x), and in my view, it’s hard to make them consistent without markets, or at least a lot more dialogue about these tradeoffs.

A major case where this is relevant is funding community-building, fundraising, and other “meta” projects. I agree that “just imagine there was a (crude) market in impact certificates, and take the actions you guess you’d take there” is a good strategy, but in that world where are organizations like CEA (or perhaps even Givewell) getting impact certificates to sell? Perhaps whenever someone starts a project they grant some of the impact equity to their local EA group (which in turn grants some of it to CEA), but if so the fraction granted would probably be small, whereas people arguing for meta often seem to be acting like it would be a majority stake.

I think starting a new charity is an interesting special case. Sometimes, it might be worth it to start a charity that would be less cost-effective on average than an existing charity is cost-effective on the margin, if you think you can get funding from people who wouldn’t have otherwise donated to cost-effective charities. However, the more the funding ends up coming from EA, the worse, and at some point it might be bad to start the charity at all. Charity Entrepreneurship (where I was an intern) has taken expectations about counterfactual donations into account in their cost-effectiveness models, or at least the ones I looked at.

In some cases, you might be taking government funding, and that funding might have been used well otherwise; I’m thinking public health funding in developing countries, but I’m not that familiar with the area, so this might be wrong.

I want to push back against a possible interpretation of this moderately strongly.

If the charity you are considering starting has a 40% chance of being 2x better than what is currently being done on the margin, and a 60% chance of doing nothing, I very likely want you to start it, naive 0.8x EV be damned. I could imagine wanting you to start it at much lower numbers than 0.8x, depending on the upside case. The key is to be able to monitor whether you are in the latter case, and stop if you are. Then you absorb a lot more money in the 40% case, and the actual EV becomes positive even if all the money comes from EAs.

If monitoring is basically impossible and your EV estimate is never going to get more refined, I think the case for not starting becomes clearer. I just think that’s actually pretty rare?

From the donor side in areas and at times where I’ve been active, I’ve generally been very happy to give ‘risky’ money to things where I trust the founders to monitor and stop or switch as appropriate, and much more conservative (usually just not giving) if I don’t. I hope and somewhat expect other donors are willing to do the same, but if they aren’t that seems like a serious failure of the funding landscape.

Evidence Action are another great example of “stop if you are in the downside case” done really well.

I agree with giving more weight to upside when you can monitor results effectively and shut down if things don’t go well, but you can actually model all of this explicitly. Maybe the model will be too imprecise to be very useful in many cases, but sensitivity analysis can help.

You can estimate the effects in the case where things go well and you scale up, and in the case where you shut down, including the effects of diverting donations from effective charities in each case, and weight the conditional expectations by the probabilities of scaling up and shutting down. If I recall correctly, this is basically what Charity Entrepreneurship has done, with shutdown within the first 1 or 2 years in the models I looked at. Shutting down minimizes costs and diverting of funding.

You wouldn’t start a charity with a negative expected impact after including all of these effects, including the effects of diverting funding from other charities.

I agree that in principle that you could model all of this out explicitly, but it’s the type of situation where I think explicit modelling can easily get you into a mess (because there are enough complicated effects that you can easily miss something which changes the answer), and also puts the cognitive work in the wrong part of the system (the job of funders is to work out what would be the best use of their resources; the job of the charities is to provide them with all relevant information to help them make the best decision).

I think impact markets (implicit or otherwise) actually handle this reasonably well. When you’re starting a charity, you’re considering investing resources in pursuit of a large payoff (which may not materialise). Because you’re accepting money to do that, you have to give up a fraction of the prospective payoff to the funders. This could change the calculus of when it’s worth launching something.

Would impact markets be useful without people doing this kind of modeling? Would they be at risk of assuming away these externalities otherwise?

This kind of externality should be accounted for by the market (although it might be that the modelling effectively happens in a distributed way rather than anyone thinking about it all).

So you might get VCs who become expert in judging when early-stage projects are a good bet. Then people thinking of starting projects can somewhat outsource the question to the VCs by asking “could we get funding for this?”

Hmm, I’m kind of skeptical. Suppose there’s a group working on eliminating plastic straws. There’s some value in doing that, but suppose that just the existence of the group takes attention away from more effective environmental interventions to the point that it does more harm than good regardless of what (positive) price you can buy its impact for. Would a market ensure that group gets no funding and does no work? Would you need to allow negative prices? Maybe within a market of eliminating plastic waste, they would go out of business since there are much more cost-effective approaches, but maybe eliminating plastic waste in general is a distraction from climate change, so that whole market shouldn’t exist.

It sounds like VCs would need to make these funding diversion externality judgements themselves, or it would be better if they could do them well.

Yeah, I totally agree that if you’re much more sophisticated than your (potential) donors you want to do this kind of analysis. I don’t think that applies in the case of what I was gesturing at with “~community projects”, which is where I was making the case for implicit impact markets.

Assuming that the buyers in the market are sophisticated:

in the straws case, they might say “we’ll pay $6 for this output” and the straw org might think “$6 is nowhere close to covering our operating costs of $82,000” and close down

I think too much work is being done by your assumption that the cost effectiveness can’t be increased. In an ideal world, the market could create competition which drives both orgs to look for efficiency improvements

I’m guessing 2 is in response to the example I removed from my comment, roughly starting a new equally cost-effective org working on the same thing as another org would be pointless and create waste. I agree that there could be efficiency improvements, but now we’re asking how much and if that justifies the co-founders’ opportunity costs and other costs. The impact of the charity now comes from a possibly only marginal increase in cost-effectiveness. That’s a completely different and much harder analysis. I’m also more skeptical of the gains in cases where EA charities are already involved, since they are already aiming to maximize cost-effectiveness.

I think that might be a good thing. And I think a norm of considering seeking non-EA funding first or at least at some point would definitely be a good thing (maybe that norm is already widespread; not sure).

But I think there would be downsides to a norm of seeking non-EA funding unrelated to the counterfactual use of the money. In particular:

This might take up more staff time

In my limited experience, seeking funding from non-EAs for EA-aligned projects can take much longer, due to things like perhaps-unnecessarily rigid application processes and a need to explain things much more thoroughly and in ways one isn’t used to (since EA funders often already have somewhat similar goals, similar ways of thinking, are more likely to know about your org/staff, etc., and that isn’t true for non-EA funders)

This might reduce one good source of feedback (i.e., feedback from EA funders might be more valuable than that from non-EA funders)

This might create more distorted incentives, e.g. incentivising doing a version of a project that’s a bit less valuable than another version but is easier to understand or more appealing for non-EAs

(Of course, those points are just possible generalisations. There will also be at least some cases in which particular non-EA funders would give better feedback and create better incentives for a particular project than EA funders would.)

Of course “non-EA funding” will vary a lot in its counterfactual value. But roughly speaking I think that if you are pulling in money from places where it wouldn’t have been so good, then on the implicit impact markets story you should get a fraction of the credit for that fundraising. Whether or not that’s worth pursuing will vary case-to-case.

Basically I agree with Michael that it’s worth considering but not always worth doing. Another way of looking at what’s happening is that starting a project which might appeal to other donors creates a non-transferrable fundraising opportunity. Such opportunities should be evaluated, and sometimes pursued.

I don’t understand the difference between certificates of impact and altruistic equity – they seem kind of the same thing to me. Is the main difference that certificates of impact are broader, whereas altruistic equity refers to certificates of impact of organizations (rather than individuals, etc.)? Or is the idea that certificates of impact would also come with a market to trade them, whereas altruistic equity wouldn’t? Either way, I don’t find it useful to make this distinction. But probably I’m just misunderstanding.

Thanks for this interesting post.

It seems to me that there are a few other relevant considerations that people should bear in mind and that, if borne in mind, should somewhat mitigate these coordination issues—in particular, moral uncertainty, empirical uncertainty, and epistemic humility. You can definitely still have these coordination issues after you take these things into account, but I think the issues would usually be blunted a bit by paying explicit attention to these considerations. E.g., if I’m in your donor of last resort scenario, then once I remember that the other donor might have good reasons for their beliefs which I’m not aware of, I move my beliefs and thus goals a little closer to theirs.

(Though paying too much attention to these considerations, or doing so in the wrong way, can also create its own issues, such as information cascades.)

So I think that a proposal for “Implicit impact markets without infrastructure” should probably include as one element a reminder for people to take these considerations into account.

I’d be curious to hear whether that seems right to you? Did you mainly leave this point out just because you were implicitly assume your audience would already have taken those considerations into account to the appropriate extent?

(I also imagine that the idea of moral trade might be relevant, but I’m not immediately sure precisely how it would affect the points you’re making.)

Moral trade is definitely relevant here. Moral trade basically deals with cases with fundamental-differences-in-values (as opposed to coordination issues from differences in available information etc.).

I haven’t thought about this super carefully, but it seems like a nice property of impact markets is that they’ll manage to simultaneously manage the moral trade issues and the coordination issues. Like in the example of donors wishing to play donor-of-last-resort it’s ambiguous whether this desire is driven by irreconcilably different values or different empirical judgements about what’s good.

I agree that these considerations would blunt the coordination issues some.

I guess I think that it should include that kind of reminder if it’s particularly important to account for these things under an implicit impact markets set-up. But I don’t think that; I think they’re important to pay attention to all of the time, and I’m not in the business (in writing this post) of providing reminders about everything that’s important.

In fact I think it’s probably slightly less important to take them into account if you have (implicit or explicit) impact markets, since the markets would relieve some of the edge that it’s otherwise so helpful to blunt via these considerations.

Hmm, I don’t think this seems quite right to me.

I think I’ve basically never thought about moral uncertainty or epistemic humility when buying bread or getting a haircut, and I think that that’s been fine.

And I think in writing this post you’re partly in the business of trying to resolve things like “donors of last resort” issues, and that that’s one of the sorts of situations where explicitly remembering the ideas of moral uncertainty and epistemic humility is especially useful, and where explicitly remembering those ideas is one of the most useful things one can do.

This seems right to me, but I don’t think this really pushes against my suggestion much. I say this because I think the goals here relate to fixing certain problems, like “donors of last resort” issues, rather than thinking of what side dishes go best with (implicit or explicit) impact markets. So I think what matters is just how much value would be added by reminding people about moral uncertainty and epistemic humility when trying to help resolve those problems—even if implicit impact markets would make those reminders less helpful, I still think they’d be among the top 3-10 most helpful things.

(I don’t think I’d say this if we were talking about actual, explicit impact markets; I’m just saying it in relation to implicit impact markets without infrastructure.)

I guess I significantly agree with all of the above, and I do think it would have been reasonable for me to mention these considerations. But since I think the considerations tend to blunt rather than solve the issues, and since I think the audience for my post will mostly be well aware of these considerations, it still feels fine to me to have omitted mention of them? (I mean, I’m glad that they’ve come up in the comments.)

I guess I’m unsure whether there’s an interesting disagreement here.

Yeah, I think I’d agree that it’s reasonable to either include or not include explicit mention of those considerations in this post, and that there’s no major disagreement here.

My original comment was not meant as criticism of this post, but rather as an extra idea—like “Maybe future efforts to move our community closer to having ‘implicit impact markets without infrastructure’, or to solve the problems that that solution is aimed at solving, should include explicit mention of those considerations?”

Here I think the idea of Shapley values is relevant and perhaps useful (though I don’t think I fully understand the concept or its usefulness myself).

Yeah, Shapley values are a particular instantiation of a way that you might think the implicit credit split would shake out. There are some theoretical arguments in favour of Shapley values, but I don’t think the case is clear-cut. However in practice they’re not going to be something we can calculate on-the-nose, so they’re probably more helpful as a concept to gesture with.