Don’t Interpret Prediction Market Prices as Probabilities

Epistemic status: most of it is right, probably

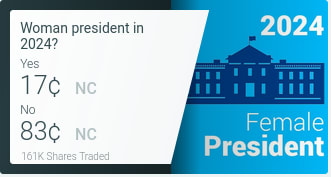

Prediction markets sell shares for future events. Here’s an example for the 2024 US presidential election:

This market allows any US person to bet on the gender of the 2024 president. Male shares and female shares are issued in equal amounts. If the demand for shares of one gender is higher than shares of the other, the price is adjusted.

At the time of writing, female shares cost 17 cents, and male shares cost 83 cents. If a female president is elected in 2024, owners of female shares will be able to cash them out for $1 each. If not, male shares can be cashed out for $1. The prices of male and female shares sum up to $1, which makes sense given that only one of them will be worth $1 in the future.

Because bettors think a female president is relatively unlikely, the price for male shares is higher. The bettors may be wrong here, but the beauty of prediction markets it that anyone can put their money where their mouth is. If you believe that a female president is more likely than a male president, you can buy female shares for 17 cents a piece. If you’re right, each of these shares will likely appreciate to $1 by 2024, almost sextupling your investment. If enough people predict a female president to be more likely, the demand for female shares will grow until they are more expensive than male shares. As such, the price of the shares reflects the predictions of everyone involved in the market.

Even if you believe a female president is, say, 25% likely, you’d still be inclined to buy a female share for 17 cents. (That is, if you’d take a 1 in 4 chance of a 500% return on investment.) The interesting thing is that whenever you buy shares, the price will move closer to the probability you perceive be true. Only when the price matches your perceived probability, the market is no longer interesting for you. Because of this, the price of a share reflects the crowd’s perceived probability of the corresponding outcome. If the market believes the probability to be 17%, the price will be 17 cents.

Or so the story goes.

$

In reality, it’s more complicated.

You’re betting in a currency and, as such, you’re betting on a currency.

Let’s say you believe a male president is about 90% likely, so you’re considering buying male shares at 83 cents. Every 83 cents you put in can only become $1, so your maximum return on investment (ROI) is about 20%. Your expected ROI is closer to about 8% because you believe there’s only a 90% chance the president will be male. Still, that’s a positive ROI, so why not make the bet?

This bet is denominated in US dollars, and it will be only resolved in 20 months or so. The problem is that US dollars are subject to inflation.

Instead of locking up our investing money in a long-term bet for nearly two years, we could instead put it in an index fund, like the S&P 500, or invest in a large number of random stocks. Both methods have historically had a 10% annualized return. That’s much better than an 8% two-year return!

Because everyone thinks this way, there will be an artificially low demand for boring long-term positions, like predicting that the next US president will be male. This will drive the price of these shares down, while driving the price of shares for low-probability events up. A share that pays out USD will never have a price that reflects the market’s perceived probability, because most people believe there are better things to invest in than USD.

There’s a solution for this, although regulators might not like it: allow people to bet bonds or shares. The famous 1 million USD bet between Warren Buffett and Protege Partners was actually not denominated in USD, but in bonds and shares.

Betting

Compared to the stock market, prediction market bets are extremely risky. If you get in at an incredibly bad time on the stock market, your portfolio might temporarily go down 50% for a year. You hit a bad streak on prediction markets, you could easily lose everything you invest. This is because of the binary nature of prediction markets: shares either resolve to $1 or to $0. Sports bettors try to counteract this by betting on a large number of events, but it remains more stressful than investing in the stock market.

As a bettor on news events, it’s even harder to diversify your bets sufficiently. The outcomes of the events you’re betting on are likely correlated.

Even if a person sees a large gap in collective reasoning, it makes perfect sense not to bet large sums on prediction markets if they don’t want to expose themselves to any risk, so you can only count on people tolerant of risks to correct prices.

Hedging

Let’s say you’re a Spanish farmer and you want to insure yourself against a cold winter where none of your bell peppers will grow. You could bet on a prediction market that the average temperature in Almeria will be below 15 degrees Celsius. That way, if a cold winter hits, you’ll get your prediction market payout, and if it doesn’t, you can sell your bell peppers.

This, I think, is a completely legitimate use of prediction markets. However, if a significant chunk of bettors is hedging, prices will slip away from the perceived true probability. Farmers don’t bet because they think the price is wrong, they’re buying insurance.

I don’t know if, historically, large prediction markets have ever started slipping as the result of hedging. In the case of the bell pepper farmers, investment funds swiftly correct the prices for weather derivatives any time they are warped by people looking for insurance.

Outcomes

Sane folks will never bet that the world is ending, no matter the payout. Rather than locking away their money, they’ll try to spend it while the world is still there. Similarly, no one will ever bet that USD goes to zero in a bet denominated in USD.

There are more subtle forms of this. Let’s say there’s a prediction market on whether most people are represented by AI lawyers by 2035. Of course, bettors will want to estimate the probability of this event. But there are other things to take into account:

The probability that money still has any value whatsoever by 2035 if AI is capable of representing people in court

The probability that money still has any value whatsoever by 2035 if AI cannot represent people in court

The probability that the world will end soon after AI starts representing people in court

If people strongly believe that soon after AI becomes capable enough to represent people in court, money/humanity will cease to exist, it makes no sense for them to bet on AI lawyers. As far as these folks are concerned, money is only worth something in a technologically dormant future. As such, they’d always bet that technology will develop slowly, even if they think it’ll happen fast.

Discussion

Prediction markets are often touted for bringing the wisdom of the people to the people. Yet, for the things this community cares most about, we should expect prediction market probabilities to be distorted by bettors’ hidden considerations.

I’m not sure if there’s any evidence of distortions actually occurring. Then again, many people still treat participating in these markets as a badge of honor rather than a real investment.

One way to get some insight into this: if prediction markets are mostly still used by hobbyists, non-monetary prediction websites like Metaculus ought to be just as reliable as prediction markets such as Polymarket.

A quick glance at the comment section suggests that people are not unanimous about which consideration is most important. This is a sign that the disconnect between prediction market prices and probabilities hasn’t been given enough thought, i.e. that this post is prompting a useful discussion. Thank you for the contribution.

Must disagree. This—and several more issues due to real money—was well known to first generation prediction market operators since the middle of the 2000′s. Almost all of them went under, which why I was so surprised to see the 1st gen model pop up again with crypto starting with Augur.

I started writing a comment, but it got too long, so I wrote it up here.

This is a good post. I think that in practice the inflation/opportunity cost consideration is by far the biggest effect here. Some reasons:

It applies a definite bias in the same direction to all long term markets (pushes them away from the extremes). Hedging might result in a one sided distortion in some cases, if really cold temperatures are bad for crops but not the other way around. But not every hedge-able market has the exact same distortion

It affects the decisions of all bettors on all markets. Whereas other distortions only apply to a niche subset such as Spanish farmers or the overly risk averse

Importantly, it impacts the decisions of more skilled predictors more strongly. This is because they can expect a higher return on average, so they have a higher opportunity cost.

E.g. for an unskilled predictor looking at a market that resolves in 1 year, they might only bet if they expect to make over a 10% return; so if their probability estimate falls outside a narrow band close to the market price it still makes sense for them to bet. But a skilled predictor might be making 50% a year on average, so a much wider range of probabilities are wiped out.

This is a big effect on Manifold because the top predictors tend to double their money every few months, so there is not much incentive for them to bet on markets longer than a year[1] unless they have a very large edge. I’m not sure how much this effect applies to real money markets

There is a loan system which helps with this somewhat, but also increases your risk exposure so it’s not clear what the overall effect is

One more point to consider, you can sell your shares before the market closes which introduces another distortion in the probability: a lot of times I am thinking not so much in what the result of a market will be, but more on what probability people are going to assign to it. So if I see a market at 50% but I know that and event that just occurred will make people update the probability to 75%, I will buy YES at 50% all the way to say 70%, wait for the market to set to 75% and then sell to make a profit, perhaps having an effect on the market by my sell. If everybody does the same, the price is more of an estimate of people’s intuition than a probability for the event. This effect is stronger in things like politics or sports, where people overprice their teams.

Yet another one: just as with stocks, big players can influence the price and sometimes make the market move the way that they want (big name is betting NO, I should probably sell my YES) which won’t reflect on the real probability.

And to your last paragraph: you can actually compare “reliability” by estimating metrics such as the log score or (I think better) the Brier score. For example, Jack, one of the most successful users at manifold.markets, compared results for the election forecasts among multiple platforms: https://firstsigma.substack.com/p/midterm-elections-forecast-comparison-analysis the results were 1. Metaculus (which is non-monetary but also has their own system of aggregating forecasts), 2. 538 (poll aggregation and statistical modeling), 3. Manifold (non-monetary* pure prediction), and then other platforms including Polymarket. So at least for the last elections, that analysis supports your argument.

*: they give you some starting “money”, you can buy with real money more, and you can cash out their “money” to real money only to send it via donations

By far the biggest problem with interpreting (certain) prediction markets as probabilities, especially in the tails, is the fee structures. PredictIt charges 10% of all winnings plus a 5% withdrawal fee. The latter fee in particular strongly disincentivizes adding new money to arbitrage small deviations in the tails. E.g. if a “yes” contract is trading at 98 cents and you are 100% sure it will happen (and you’re correct), investing 98 cents now and withdrawing the resulting $1 after the market turns over (even if it ends tomorrow, so we abstract from inflation), will yield a loss of 0.98-((1-.98)*0.9+0.98)*0.95 = 3.19 cents. This problem is much smaller when betting on long shot outcomes, so it will tend to push prediction markets away from “certainty” on outcomes. You can make a copy of this calculator for PredictIt to see the effects.

This problem is somewhat ameliorated by people making multiple sequential bets (this amortizes the 5% withdrawal fee over more bets—in the limit, I think that if you made an infinite number of (on average winning) bets, the 5% withdrawal fee would become just a fee on profits), but I think it’s a significant issue in the tails.

Correct, and it is just one further issue with any prediction market mechanism deployed on a real money (or a fiat currency impostering as a real money, for the avoidance of doubt).

Regarding the inflation/opportunity cost, I’m curious as to its effect in a more efficient market. If I believe that the probability is q but the market currently values the share of YES at a price reflecting some probability p<q, then I should believe that the market will update itself upward. That is, I expect my personal information and considerations to be eventually discovered by other people and the price to reflect that (especially if after I buy I’ll also share my information and considerations). This would mean that I don’t have to wait a long time before the price goes up, and by then I can sell.

However, I don’t think we should expect the price to go all the way up to q. In the simple case where everyone believes the probability is q, and that it would remain q until the market closes, and everyone is rational and risk-neutral, the price should reflect the expected benefit considering the opportunity cost, so that one would value buying YES and investing in other alternatives equally.

In such an efficient market, at the limit, I’d expect no difference between holding on to some stocks compared to buying and selling any time at whatever the price is. Therefore, the price pt at each time t<T (the closing time) should really be such that the following holds:

q⋅1−pt=ptrT−t, where r is the interest rate. Equivalently,

pt=q1+rT−t.

A proper prediction market (virtual one) is designed to make people reveal their expectations early. That solves the problem of “waiting for discovery”.

I can confirm that for this reason, and a few more, a prediction market mechanism works much better in a well-designed virtual market economy where bets are not denominated in a monetary currency. In fact that’s why I sold Redmonitor, a real money prediction market I founded in 2004 only 4 years later, in 2008 and started a virtual one.

Just to highlight a particular example: suppose you have a prediction market on “How much will be inflation of USD over the next 2 years?”, that is priced in USD.

Regarding the question of locking up money for so long, do prediction markets generally require bets to be 100% funded? That seems like it makes these bets unnecessarily capital-intensive.

In futures markets bets are generally margined and marked to market daily (or more often). If the market moves in your favor, you could withdraw money accordingly, but if it moves against you then you must add more capital or else liquidate your position. Overall this allows placing trades (sometimes long-term trades) without having to put up as much capital.

The amount of margin required for a particular bet generally depends on the liquidity and volatility of the market in question.

Augur used to have a set of markets called “Chad Edition” where you could wager Ethereum instead of USD

https://augur.net/blog/augur-ce/

So think the outcomes point is the strongest here.

When I’m thinking about how seriously to take their prediction market percentages I consider:

Do the outcomes have the right incentives

Is there sufficient liquidity to think the number is a proper representation (maybe $1000 or M$1000)

Is the probability over 95% or smaller than 5% (in both cases it becomes much less clear)

Outside of that using prices as probabilities is fine.

Again your hedging bit is right but just rarely happens in the kinds of markets people quote on this forum.

Thanks for writing. I think you are technically right which is good.

I personally think the inflation section is just as important. People won’t make a long-term bet denominated in USD with an expected ROI lower than inflation. This also affects markets that aren’t 95% lopsided.

Yeah you’re right.