EA and tackling racism

As I write, the world is gripped in shockwaves of hurt and anger about the recent death of George Floyd and the issue of racism.

And many are asking what effective altruism (or EA) has to say about this (see here, or here, or here)

I have engaged with the EA community for many years, but I don’t consider myself an authoritative voice on effective altruism.

I am a non-white person living in a predominantly white country, but I don’t consider myself an authoritative voice on racism.

But I wanted to share some thoughts.

First of all, let’s just acknowledge that the EA community has been—in its own way—fighting against a particular form of racism right from the earliest days of the EA movement.

What greater racism is there than the horrifically uneven distribution of resources between people all because of an accident of their birth? And how disgusting that some of the worst off should be condemned to death as a result?

Is not the obscene wealth of the developed world in the face of tractable, cost-effective ways of saving lives in the developing world wholly unjustifiable if we were treating people as equals, regardless of where they are, and regardless of the colour of their skin?

I still find this argument compelling. And I would encourage the EA movement to be proud of what it has done, proud of the hundreds of millions of dollars already moved in an expression of global solidarity to people around the world.

But in some ways this argument feels insular.

Is EA really all about taking every question and twisting it back to malaria nets and AI risk?

Those of us who, like me, have spent most of their lives in the UK and are old enough will remember the name of Stephen Lawrence. And for those of us, like me, who have spent a substantial chunk of their lives in charities in South East London, his name will have followed us like a ghost.

For those who have sensed or lived systemic racism, I do think that the EA way of thinking has something to offer. And something more than “donate to the Against Malaria Foundation”.

In this post, I set out some thoughts. I would love to have provided good solutions, like “this is the best place to donate” or “this is the best thing to do” but the range of existing thoughts on this topic is too broad and complex for me to be able to do that now.

I think the most important thing that an EA mindset has to offer is this:

EA is not just about finding the right answers, it’s about asking fundamental questions too.

The effective altruism movement is unusual. Not only do EA-minded people answer questions like “what is the best way to improve global health” (finding the right answers). The EA approach also poses questions like “what is the best cause area to tackle, is it global health, or is it existential risk, or is it something else?” (asking more fundamental questions).

At first glance, asking the more fundamental questions about cause prioritisation risks subverting our goal. We may conclude that tackling an intractable thing like systemic racism isn’t really the best bang for your buck, and then we’re back to turning everything into malaria nets again.

On second glance, it’s clear that EA does have something to offer.

For example, someone who cares about animals would be encouraged by an effective altruist to consider the different “sub-causes” within the animal cause area, and provided data and arguments about why some are much more effective than others.

So in that vein, here are some thoughts about tackling systemic racism as seen through (my interpretation of) an EA lens.

These thoughts will raise more questions than answers. My hope and intention is that these are good, useful questions.

Before I get started, just an observation: achieving change is hard. Especially in a tough area like this. It will require substantial amounts of financial input and lots of capable dedicated people putting in huge amounts of effort, as well as good collaboration between them. What follows is thinking to help prioritise and make decisions about that effort.

Most of the rest of this post may feel a bit technical. Readers who don’t want to get caught up in my proposed approach are encouraged to skip to the section headed “Final thoughts”.

--------------------------

The first step is to work out what we want to achieve. My understanding of what we want is to tackle systemic racism at a national level (e.g. in the US, or the UK).

Note that this goal does not presume that the only outcomes we care about are at the level of the police. It’s possible for George Floyd’s death to be the clarion call, but for the ripples to reach far and wide beyond the judicial system.

I start by distinguishing between

direct social interventions

population-wide campaigning to change social norms, and

lobbying work to change policy.

1. Direct social interventions

In finding direct social interventions, I distinguish between

We have the evidence, but nobody is implementing it

People are doing things, but the evidence for their effectiveness is weak or even non-existent

(Projects that people are working on *and* which have strong evidence are much rarer than we might hope)

In both categories, I suggest we consider:

What does the evidence say?

How cost-effective do we think it’s going to be?

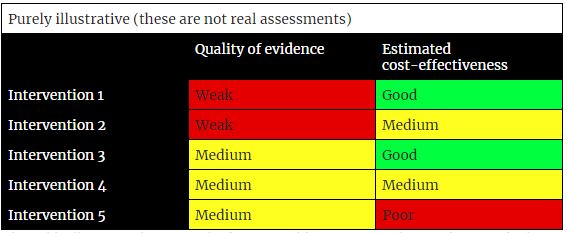

This table illustrates the sort of thinking I would propose. For the avoidance of doubt, this is not a real assessment, it’s just an illustration to show what a real assessment might look like.

Quality of evidence

The effective altruism movement tends to have a thread of scepticism about the effectiveness of most social interventions (see, e.g. this post by my organisation SoGive or this post by 80,000 hours).

If you are convinced by this, then you want social interventions which have a good evidence base behind them.

I did a quick search for RCTs on tackling racism. The only relevant piece of evidence I could find was Platz et al 2017, which found that diversity training for police recruits was effective at stopping a decline in values. However this was based on a not-particularly-large sample size and I couldn’t find any more studies in the google scholar search, the papers cited by Platz et al 2017, or in the papers which cited Platz et al 2017.

More evidence may exist (my search was very quick).

Once we have the evidence, we assess it for its quality. This includes considering the quality of controls used (randomised is generally better), sample size, risk of file drawer effects, risk of moving the goalposts, risks of HARKing (hypothesising after the results are known), risks from studies not being blinded (where applicable).

If the intervention is being done by an existing charity, the work is often fairly weakly evidenced (it’s more common for someone to start a charity first and then seek evidence than the other way round, and the incentives for robust evidence are not strong once a charity is already running).

The effective altruist tendency to focus on evidence stems from a desire to genuinely achieve change.

Cost-effectiveness

The effective altruism movement loves cost-effectiveness. This isn’t stinginess; it’s because if the funds available are finite (which they always are) then you want to do as much good as you can with the money available.

Estimating cost-effectiveness of an intervention is often hard. Especially when there is not an established organisation already doing the intervention.

An organisation I founded called SoGive has developed techniques for estimating the cost per output of an existing charity intervention.

And for situations where this data doesn’t exist, here is a sketch of an approach for a very quick-and-dirty cost-effectiveness model:

Assume that the cost per intervention is £500 (source: a review of the SoGive database of cost per output across several charitable interventions/activities working directly with people in the UK suggests a cost between £100 and £3,000 is likely; £500 is a representative figure (technically, it’s the “geometric mean”))

Build a model of the outcomes suggested by the evidence (e.g. Notional funding amount of £10k → 20 HR departments supported with unconscious bias training → 100 cases of people getting a job they otherwise wouldn’t have got) This could be turned into a spreadsheet model with confidence intervals including pessimistic and optimistic estimates

These estimates of the cost per outcome can be compared with each other

This analysis can help to narrow down a shortlist of more effective interventions for people to work on / fund.

2. Campaigning to change social norms

For changing social norms and behaviours, the most well-evidenced intervention that I know of is the Saturation + model followed by Development Media International (DMI). This is essentially about exposing the target audience to a high frequency of messaging. This is not dissimilar to applying the power of advertising to social change.

To my knowledge, evidence for the Saturation + model exists when it comes to improving public health, but not for changing social norms like racism. It would certainly need a new evidence base before its effectiveness in this context were established, however the existing evidence should at least give us hope.

I’ve only referred to Saturation + in this section. It may be that another, better model exists; a full review of other alternatives should ideally be performed.

Again, a cost-effectiveness model would be needed here. This could be determined by looking at the existing models for DMI’s work and making adjustments (and of course, it’s very hard to know how to adjust for the fact that the method is being used in a very different context to public health)

3. Lobbying to change policy

Having defined the scope as tackling systemic racism in any context, we have to consider which systems or institutions are candidates for improvement.

Before we do that, let’s remember the horrific video of George Floyd’s neck being knelt on as he lay defenceless on the floor, with voices questioning whether the police really needed to be so heavy-handed. It was brutal.

But how do we choose between tackling police brutality and the many other ways that society brutalises people of colour?

I wouldn’t claim that the below list is comprehensive, and if someone properly conducted this review, they would need to consider which rows to include.

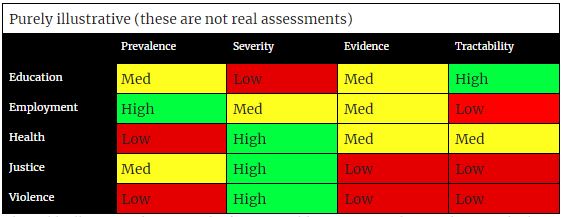

This table illustrates the sort of thinking I would propose. For the avoidance of doubt, this is not a real assessment, it’s just an illustration to show what a real assessment might look like.

Prevalence

Prevalence considers how many people are affected by this issue. E.g. education-related racism might be prevalent (because everyone at least starts going to school) or not so prevalent (because only some schools have a racism problem). Health might have low prevalence (because some people have relatively few health needs).

This is best assessed by literally trying to size the problem; e.g. how many people in the US / UK/ wherever are suffering from this. This can be estimated from existing research on the topic, or where such research doesn’t exist or is inadequate, then new primary research may be needed.

Severity

This is a tough assessment. It’s asking how bad is it (e.g.) to be discriminated against in an educational context compared to an employment context. It could be assessed by a combination of qualitative research (e.g. reviewing interviews with people who have suffered from the problem) and quantitative research (e.g. how often do racist incidents of various levels of severity occur?)

Methods which are not really good enough, but which would be sufficient in the absence of better research , include a quick survey asking a sample of respondents to compare different outcomes for how bad they are, or for a really quick and dirty first attempt, the researcher could simply use their own judgement on what they think would be worse. While this is clearly inadequate, it is certainly better than the common alternative of making this judgement implicitly (which is inevitably what is happening when someone—consciously or otherwise—chooses to support one of these areas and not another).

Evidence that the problem is real

For any of these areas, there will be some people who believe that the racism problem either doesn’t exist, or at least is overblown.

This factor is important for two reasons:

Reason 1: If the problem isn’t real, the intervention won’t be effective

Reason 2: If the evidence is weak, it may make lobbying harder

The importance of reason 1 depends on your expectations of the skews/biases in the evidence base. If you think that publication bias, for example, leads to a skew in the evidence towards sensationalist results which indicate racism, then reason 1 is important. However it may be that the evidence base around the existence/prevalence of racism is just as likely to include the bias of wanting to show that racism is overblown/non-existent.

The techniques used above to assess the quality of evidence would largely be applicable here.

Tractability

Factors that may influence tractability include whether the institution can be changed without undergoing substantial costs, whether there are entrenched cultural norms which may invalidate any policy change, and whether there is public opinion onside.

And lastly lobbying needs a cost-effectiveness model too. This would involve looking at past lobbying efforts and estimating how much had been spent on the lobbying effort in order to achieve the policy change. This can be a fraught calculation for various reasons.

Bringing it all together

The last step is to take the cost-effectiveness estimates from the best option(s) in each of direct social interventions, campaigning to change social norms, and lobbying for policy change. Then we compare them.

When doing so, it would be important to consider the uncertainty in each area: these cost-effectiveness estimates are performed quite crudely, and should not be taken literally.

If it can be concluded from this that one area clearly outperforms another, then we have successfully narrowed our focus area.

--------------------------

Final thoughts

I wrote this partly because I think racism matters.

And I wrote it because I wanted to illustrate that EA can be a tool that can be applied in so many contexts.

It is intended to illustrate the following properties of the effective altruism approach

Being led by the heart, and not letting our heart be limited in where it takes us

George Floyd’s death might have motivated us, but that doesn’t mean that the justice system is the only place where racism is prevalent

Reason and evidence, as an expression of caring about making real change

Evidence matters because we are not devoting our time or money to these issues for tokenistic reasons, we do it because we want to effect real change

Cost-effectiveness, because nobody is a statistic

If, for the same money/time, we can help more people suffer less racism, this is great. Because every instance of racism averted counts.

The systematic approach I’ve highlighted here might seem almost callous. But to my mind it’s a sign of really caring.

Another feature of effective altruism is humility. So in that vein let me reiterate that there may be many things that I’ve got wrong here, both in terms of my thinking of what is the best thing to do for tackling racism, and in terms of capturing what EA really is.

If I were to pick one thing that’s most likely to be a mistake, it’s the omission of further research from the list of (1) direct social interventions (2) campaigning to change social norms (3) lobbying for policy change. I did this because EA isn’t just about paralysis by analysis. It’s about doing as much as it’s about thinking.

But the approach set out above is based heavily on the evidence, and if systemic racism or unconscious bias extends as far as the institutions performing the research, this jeopardises our evidence base.

And lastly our doubts about the malign influence of institutional prejudice or unconscious bias do not just reach as far as our data.

They should reach ourselves as well.

In the UK there’s a campaign group called Charity So White which tackles institutional racism within the charity sector. To finally raise a question too broad for me to answer here: Do we also need an “EA So White” too?

- Red-teaming contest: demographics and power structures in EA by (31 Aug 2022 4:36 UTC; 110 points)

- 's comment on Where is the Social Justice in EA? by (5 Apr 2022 5:30 UTC; 85 points)

- Noticing the skulls, longtermism edition by (5 Oct 2021 7:08 UTC; 70 points)

- EA Updates for June 2020 by (3 Jul 2020 11:34 UTC; 33 points)

- Please stand with the Asian diaspora by (20 Mar 2021 1:05 UTC; 23 points)

- 's comment on Noticing the skulls, longtermism edition by (5 Oct 2021 15:23 UTC; 22 points)

- 's comment on Effective Altruism Approach on Social Inequality—Marginalized Communities by (16 Jun 2023 10:28 UTC; 5 points)

- How focused do you think EA is on topics of race and gender equity/justice, human rights, and anti-discrimination? What do you think are factors that shape the community’s focus? by (29 May 2023 9:56 UTC; 3 points)

- Promoting climate considerations within existing high priority areas of work by (27 Jul 2022 15:27 UTC; 2 points)

I broadly agree, but in my view the important part to emphasize is what you said on the final thoughts (about seeking to ask more questions about this to ourselves and as a community) and less on intervention recommendations.

I bite this bullet. I think you do ultimately need to circle back to the malaria nets (especially if you are talking more about directing money than about directing labor). I say this as someone who considers myself as much a part of the social justice movement as I do part of the EA movement.Realistically, I don’t think it’s really plausible that tackling stuff in high income countries is going to be more morally important than malaria net-type activities, at least when it comes to fungible resources such as donations (the picture gets more complex with respect to direct work of course). It’s good to think about what the cost-effective ways to improve matters in high income countries might be, but realistically I bet once you start crunching numbers you will probably find that malaria-net-type-activities should still the top priority by a wide margin if you are dealing with fungible resources. I think the logical conclusions of anti-racist/anti-colonialist thought converge upon this as well. In my view, the things that social justice activists are fighting for ultimately do come down to the basics of food, shelter, medical care, and the scale of that fight has always been global even if the more visible portion generally plays out on ones more local circles.

However, I still think putting thought into how one would design such interventions should be encouraged, because:

I agree with this, and would encourage more emphasis on this. The EA community (especially on the rationality/lesswrong part of the community) puts a lot of effort into getting rid of cognitive biases. But when it comes to acknowledging and internally correcting for the types of biases which result from growing up in a society which is built upon exploitation, I don’t really think the EA community does better than any other randomly selected group of people who are from a similar demographic (lets say, randomly selected people who went to prestigious universities). And that’s kind of weird. We’re a group of people who are trying to achieve social impact. We’re often people who wield considerable resources and have to work with power structures all the time. It’s a bit concerning that the community level of knowledge of the bodies of work that deal with these issues is just average.I don’t really mean this as a call to action (realistically, I think given the low current state of awareness it seems probable that attempting action is going to result in misguided or heavy-handed solutions). What I do suggest is—a lot of you spend some of your spare time reading and thinking about cognitive biases, trying to better understand yourself and the world, and consider this a worthwhile activity. I think, it would be worth applying a similar spirit to spending time to really understand these issues as well.

What are some of the biases you’re thinking of here? And are there any groups of people that you think are especially good at correcting for these biases?

My impression of the EA bubble is that it leans left-libertarian; I’ve seen a lot of discussion of criminal justice reform and issues with policing there (compared to e.g. the parts of the mainstream media dominated by people from prestigious universities).

I suppose the average EA might be more supportive of capitalism than the average graduate of a prestigious university, but I struggle to see that as an example of bias rather than as a focus on the importance of certain outcomes (e.g. average living standards vs. higher equity within society).

The longer answer to this question: I am not sure how to give a productive answer to this question. In the classic “cognitive bias” literature, people tend to immediately accept that the biases exist once they learn about them (…as long as you don’t point them out right at the moment they are engaged in them). That is not the case for these issues.

I had to think carefully about how to answer because (when speaking to the aforementioned “randomly selected people who went to prestigious universities”, as well as when speaking to EAs) such issues can be controversial and trigger defensiveness. These topics are political and cannot be de-politicized, I don’t think there is any bias I can simply state that isn’t going to be upvoted by those who agree and dismissed as a controversial political opinion by those who don’t already agree, which isn’t helpful.

It’s analogous to if you walked into a random town hall and proclaimed “There’s a lot of anthropomorphic bias going on in this community, for example look at all the religiosity” or “There’s a lot of species-ism going on in this community, look at all the meat eating”. You would not necessarily make any progress on getting people to understand. The only people who would understand are those who know exactly what you mean and already agree with you. In some circles, the level of understanding would be such that people would get it. In others, such statements would produce minor defensiveness and hostility. The level of “understanding” vs “defensiveness and hostility” in the EA community regarding these issues is similar to that of randomly selected prestigious university students (that is, much more understanding than the population average, but less than ideal). As with “anthropomorphic bias” and as with “speciesism”, there are some communities where certain concepts are implicitly understood by most people and need no explanation, and some communities where they aren’t. It comes down to what someone’s point of view is.

Acquiring an accurate point of view, and moving a community towards an accurate point of view, is a long process of truth seeking. It is a process of un-learning a lot of things that you very implicitly hold true. It wouldn’t work to just list biases. If I start listing out things like (unfortunately poorly named) “privilege-blindness” and (unfortunately poorly named) “white-fragility” I doubt it’s not going to have any positive effect other than to make people who already agree nod to themselves, while other people roll their eyes, and other people google the terms and then roll their eyes. Criticizing things such that something actually goes through is pretty hard.

The productive process involves talking to individual people, hearing their stories, having first-hand exposure to things, reading a variety of writings on the topic and evaluating them. I think a lot of people think of these issues as “identity political topics” or “topics that affect those less fortunate” or “poorly formed arguments to be dismissed”. I think progress occurs when we frame-shift towards thinking of them as “practical every day issues that affect our lives”, and “how can I better articulate these real issues to myself and others” and “these issues are important factors in generating global inequality and suffering, an issue which affects us all”.

Something which might be a useful contribution from someone familiar with the topic would be to write about it in EA-friendly terms. Practical every day issues don’t have to be expressed in “poorly formed arguments”. If the material could be expressed in well formed arguments (or in arguments which the EA community can recognise as well formed), I think it would gain a lot more traction in the community.

Well, I do think discussion of it is good, but if you’re referring to resources directed to the cause area...it’s not that I want EAs to re-direct resources away from low-income countries to instead solving disparities in high income countries, and I don’t necessarily consider this related to the self-criticism as a community issue. I haven’t really looked into this issue, but: on prior intuition I’d be surprised if American criminal justice reform compares very favorably in terms of cost-effectiveness to e.g. GiveWell top charities, reforms in low income countries, or reforms regarding other issues. (Of course, prior intuitions aren’t a good way to make these judgements, so right now that’s just a “strong opinion, weakly held”.)

My stance is basically no on redirecting resources away from basic interventions in low income countries and towards other stuff, but yes on advocating that each individual tries to become more self-reflective and knowledgeable about these issues.

I agree, that’s not an example of bias. This is one of those situations where a word gets too big to be useful—“supportive of capitalism” has come to stand for a uselessly large range of concepts. The same person might be critical about private property, or think it has sinister/exploitative roots, and also support sensible growth focused economic policies which improve outcomes via market forces.

I think the fact that EA has common sense appeal to a wide variety of people with various ideas is a great feature. If you are actually focused on doing the most good you will start becoming less abstractly ideological and more practical and I think that is the right way to be. (Although I think a lot of EAs unfortunately stay abstract and end up supporting anything that’s labeled “EA”, which is also wrong).

My main point is that if someone is serious about doing the most good, and is working on a topic that requires a broad knowledge base, then a reasonable understanding the structural roots of inequality (including how gender and race and class and geopolitics play into it) should be one part of their practical toolkit. In my personal opinion, while a good understanding of this sort of thing generally does lead to a certain political outlook, it’s really more about adding things to your conceptual toolbox than it is about which -ism you rally around.

This is a tough question to answer properly, both because it is complicated and because I think not everyone will like the answer. There is a short answer and a long answer.

Here is the short answer. I’ll put the long answer in a different comment.

Refer to Sanjay’s statement above

At time of writing, this is sitting at negative-5 karma. Maybe it won’t stay there, but this innocuous comment was sufficiently controversial that it’s there now. Why is that? Is anything written there wrong? I think it’s a very mild comment pointing out an obviously true fact—that a communities should also be self-reflective and self-critical when discussing structural racism. Normally EAs love self-critical, skeptical behavior. What is different here? Even people who believe that “all people matter equally” and “racism is bad” are still very resistant to having self-critical discussions about it.

I think that understanding the psychology of defensiveness surrounding the response to comments such as this one is the key to understanding the sorts of biases I’m talking about here. (And to be clear—I don’t think this push back against this line of criticism is specific to the EA community, I think the EA community is responding as any demographically similar group would...meaning, this is general civilizational inadequacy at work, not something about EA in particular)

“It’s a bit concerning that the community level of knowledge of the bodies of work that deal with these issues is just average”—I do think there are valuable lessons to be drawn from the literature, unfortunately a) lots of the work is low quality or under-evidenced b) discussion of these issues often ends up being highly divisive, whilst not changing many people’s minds

a) Well, I think the “most work is low-quality aspect” is true, but also fully-general to almost everything (even EA). Engagement requires doing that filtering process.

b) I think seeking not to be “divisive” here isn’t possible—issues of inequality on global scales and ethnic tension on local scales are in part caused by some groups of humans using violence to lock another group of humans out of access to resources. Even for me to point that out is inherently divisive. Those who feel aligned with the higher-power group will tend to feel defensive and will wish not to discuss the topic, while those who feel aligned with lower-power groups as well as those who have fully internalized that all people matter equally will tend to feel resentful about the state of affairs and will keep bringing up the topic. The process of mind changing is slow, but I think if one tries to let go of in-group biases (especially, recognizing that the biases exist) and internalizes that everyone matters equally, one will tend to shift in attitude.

What do you think about the fact that many in the field are pretty open that they are pursuing enquiry on how to achieve an ideology and not neutral enquiry (using lines like all fields are ideological whether they know it or not)?

Thanks for this post. I am trying to think about charities, like CEA’s Groups team recommendations, in this light. Besides, I think someone should deeply think about how EAs should react to the possibility of social changes – when we are more likely to reach a tipping point leading to a very impactful event (or, in a more pessimistic tone, where it can escalate into catastrophe). For instance, in situations like this, neglectedness is probably a bad heuristics—as remarked by A. Broi.

On the other hand, this sounds inaccurate, if not unfair, to me:

I don’t actually want to argue about “what should EAs do”. Just like you, all I want is to share a thought – in my case, my deep realization that attention is a scarce resource. I had this “epiphany” on Monday, when I read that a new Ebola outbreak had been detected in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In the same week, same country, the High Commissioner for Human Rights denounced the massacre about 1,300 civilians. Which reminded me this region has faced ethnic and political violence since the 1990s, when the First and the Second Congo Wars happened, leading to death more than 5 million people.

But most people have never even heard of it – I hadn’t, until three years ago, when I had my first contact with EA. Likewise, if the refugee crisis in Europe is a hot topic in world politics, the fact that Uganda is home to more than 1.4 million refugees (mainly from DRC and Sudan) is largely ignored—but not by GD.

So, I didn’t really see your point with this:

In response to:

So, I didn’t really see your point with this:

There are some who would argue that you can’t tackle such a structural issue without looking at yourselves too, and understanding your own perspectives, biases and privileges.

How important is this issue? I don’t know

How much of a problem is this for EA? I don’t know

I didn’t want to try to answer those questions in this piece (it’s long enough as it is!)

But I worried that tackling the topic of racism without even mentioning the risk that this might be a problem risked seeming over-confident.

Thank you Ramiro. If I understand correctly your point around attention being a scarce resource, you are challenging whether we should pay too much attention to topics like racism at a time when lots of people are thinking about it, while other more neglected issues (like the Ebola outbreak and other issues you mentioned) may be higher impact things to pay attention to.

I think this makes a lot of sense.

But I don’t think everyone will be so cause neutral, and I think EA ways of thinking still have something to for people who want to focus on a specific cause.

Actually, I think that, before BLM, I underestimated the impact of racism (probably because it’s hard to evaluate and compare current interventions to GW’s charity recommendations); also, given BLM and the possibility of systemic change, I now think it might be more tractable - this might even be a social urgency.

But what most bothered me in your text was:

a) EA does not reduce everything to mosquito nets and AI—the problem is that almost no one else was paying attention to these issues before, and they’re really important;

b) the reason why most people don’t think about it is that the concerned populations are neglected—they’re seen as having less value than the average life in the developed world. Moreover, in the case of global health and poverty interventions in poor countries (mostly African countries), I think it’s quite plausible that racism (i.e., ethnic conflicts, brutal colonial past, indifference from developed countries) is partially responsible for those problems (neglected diseases and extreme poverty). For instance, racism was a key issue in previous humanitarian tragedies, such as the Great Famines in Ireland and Bengal.

In my head I am playing with the idea of a network/organization that could loosely, informally represent the general EA community and make some kind of public statement, like an open letter or petition, on our general behalf. It would be newsworthy and send a strong signal to policymakers, organizations etc.

Of course it would have to be carried out to high epistemic standards and with caution that we don’t go making political statements willy nilly or against the views of significant numbers of EAs. But it could be very valuable if used responsibly.

Thanks for this post. The EA movement will be a flawed instrument for doing the most good until it addresses the the racism, cissexism (and, I may add, Western-centrism) in its midst. We need an organisation to supervise EA charities on these issues.

Thanks a lot for this post!

Unfortunately, there is still racial profiling and this must be recognized. Of course, many ethical circles are now fighting against it and so on, but such cases still occur. Especially in provincial environments. By the way, I found a lot of essays on racial profiling here https://edubirdie.com/examples/racial-profiling/ , you can read them if you are not deep enough into the issue, so the details of it will be more than clear. I hope it will be useful to you.

Thanks for this post. In my view, one of the most important elements of the EA approach is the expanding moral circle. The persistence of systemic racism in the US (where I live) is compelling evidence that we have a long way to go in expanding the moral circle. Writ large, the US moral circle hasn’t even expanded enough to include people of different races within our own country. I think this inability to address systemic racism is an important problem that could have a negative effect on the trajectory of humanity. In the US, it’s obvious that systemic racism impedes our ability to self-govern responsibly. Racial animus motivates people toward political actions that are harmful and irrational. (For a recent example, look at the decision to further restrict H-1B visas.) Racism (which may manifest as xenophobia) also impedes our ability to coordinate internationally—which is pretty important for responding to existential risks. So I tend to think that the value of addressing systemic racism is probably undervalued by the average EA.

Editing to add another dimension in which I think systemic racism is probably undervalued. If you believe that positive qualities like intelligence are distributed across different racial groups (and genders, etc), then you would expect roles of leadership and influence to be distributed across those groups. To me, the fact that our leadership, etc. is unrepresentative is an indicator that we are not using our human capital most effectively. We are losing out on ideas, talents, productivity, etc. Efforts to increase representation (sometimes called diversity efforts) can help us get a more efficient use of human capital.

I also just think racial equality is a good in itself—but I’m not a strict consequentialist / utilitarian as many in EA are.

Hi, interesting post. I’m new here so please excuse faults in my comment.

“Is EA really all about taking every question and twisting it back to malaria nets and AI risk?”

Based on this article https://80000hours.org/career-guide/most-pressing-problems/:

“There’s no point working on a problem if you can’t find any roles that are a good fit for you – you won’t be satisfied or have much impact.”

“If you’re already an expert in a problem, then it’s probably best to work within your area of expertise. It wouldn’t make sense for, say, an economist who’s crushing it to switch into something totally different. However, you could still use the framework to narrow down sub-fields e.g. development economics vs. employment policy.”

In my understanding, EA also considers personal fit and thus working on other problems if the person can make a bigger impact from there. For example, if somebody alive today possesses the same aptitudes as (with all due respect) Martin Luther King Jr., then he’d be better in tackling Racism than Malaria nets and AI risks.

That’s an interesting point.

EA career advice often starts with a pressing global problem, thinks about what skills could help solve that problem, and then recommends that you personally go acquire those skills. What if we ask the question from the other direction: For any given skillset or background, how can EA nudge people towards more impactful careers?

Racism causes a lot of suffering, and some of the best minds of this generation are working towards ending it. If EA helped those people find the most effective ways to advance racial justice, it would benefit the world and expose more people to EA ways of thinking.

One way the EA movement could succeed over the next few decades is by becoming a source of information for a broad popular audience about how to be more impactful in the most popular causes.

This is a good marketing strategy, but it risks becoming “Moloch;” The popular cause (originally intended as marketing) might eat away the others.

Other than that, why do you expect EA to more successful than other groups? Big, popular, entrenched problems are seldom easily exploitable. In the case of inequality; There are some conservative suggestions I have heard that seem worth trying out (e.g., public minority-only schools with strong selection filters and high academic/behavioral standards), but are readily dismissed because they are not politically desirable. So the challenge is to present ideas that are simultaneously appealing and effective and actualizable and new. I don’t see EA having much luck. Posting this from the Middle East, it is laughably clear to me that this is very ineffective use of resources.