The following is a copy of Founders Pledge’s new report Global Catastrophic Nuclear Risk: A Guide for Philanthropists. Readers who prefer footnotes to endnotes can find a Google Doc here.

Special thanks to Matt Lerner (Founders Pledge), Jim Scouras (JHU Applied Physics Laboratory), and Matt Gentzel (Longview Philanthropy) for reviewing the report and for their invaluable input and advice.

A full list of the many people who contributed to this project is in the section on “Acknowledgements and Disclaimers.” The report is long, and I expect most people will not want to read the full document. Below is a short summary, followed by the full report.

tl;dr

There has been a large reduction in philanthropic funding, coincident with new challenges in nuclear security. Specifically:

China and the “Three Body Problem.” The apparent ambitions of the Chinese Communist Party to massively expand its nuclear arsenal threaten to create a “Three Body Problem” of unstable deterrence dynamics between three nuclear superpowers — the United States, Russia, and China — whose arsenals dwarf the other nuclear powers. Deterrence was built on duels, not truels, and we don’t know how to approach this new problem.

Technological Disruption. Advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence have the potential to undermine (but also to strengthen) strategic stability, depending on their applications. For more, see Founders Pledge’s research on autonomous weapons and military AI.

Funding Shortfalls. The MacArthur Foundation is withdrawing from the nuclear field, leaving a major funding shortfall, and reducing the total philanthropic funding per year to about $30 million. (For comparison, the three CEOs of Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Raytheon alone took home more than $60 million in 2021. For another comparison, the budget of Oppenheimer was more than three times as much as philanthropists now spend on preventing nuclear war.)

A key insight for funders who value cost-effectiveness is that the negative effects of large-scale nuclear wars are disproportionately worse than the negative effects of more limited nuclear exchanges. In other words, nuclear wars are not created equal and the costs of nuclear war increase super-linearly with the size of nuclear war. All nuclear use is horrific, but the largest wars — thermonuclear exchange between the great powers — have the potential to threaten modern civilization and potentially alter the Earth’s climate, triggering mass starvation. Uncertainties abound — the science around nuclear winter is shoddy, civilizational collapse is difficult to model, and the tractability of escalation control is unknown — but this basic insight remains unchanged. Other features further define the structure of the problem:

Funders, experts, and decision-makers face deep uncertainty about the effectiveness of interventions — we often simply do not know what would work best, and have no way of finding out.

Accidents happen — the problems of nuclear crisis management and escalation control are likely here to stay, and cannot be ignored.

What comes down can go back up — Cold War arsenal reductions are not guaranteed to be sticky, and some trends suggest that states are interested in arming; the magnitude of nuclear risk could increase significantly in the near future.

From the structure of the problem, philanthropists can derive heuristics that act as impact multipliers (for more on impact multipliers and relative cost-effectiveness under uncertainty, see “How we think about charity evaluation” and the methodological work of the Founders Pledge climate team):

Funders ought to focus on minimizing war damage. This ultimate goal may diverge from intermediate goals like disarmament, non-use, etc.

In light of uncertainty about intervention effectiveness, funders ought to prioritize neglected strategies.

Funders can multiply their impact by focusing on “great powers.”

Funders can multiply their impact by focusing on policy advocacy to leverage societal resources.

The principle of “robust diversification” can help guide effective giving under the conditions described above.

When combining these insights with analysis of funding databases, we are once again pushed towards prioritizing philanthropic interventions that seek to minimize damage after the first nuclear weapon has gone off, especially by escalation control, war limitation, and war termination. For more on this, see “Philanthropy to the Right of Boom” and “Call Me, Maybe? Hotlines and Global Catastrophic Risks.” To summarize:

“Right of boom” interventions — focusing on problems arising after the first use of nuclear weapons, such as escalation control — are an important part of risk reduction.

These very interventions have been severely neglected by philanthropic funders, possibly for ideological reasons.

These facts suggest that prioritizing “right of boom” interventions is a promising impact multiplier for funders on the margin.

Crucially, we can use these heuristics to build grantmaking strategies for nuclear security, and to identify potentially promising projects for effective philanthropy.

Now, the full report:

Acknowledgements and Disclaimers

I am thankful to the many experts who have contributed to this project with their insight, feedback, and critiques, including in semi-structured interviews. The analysis and views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of anyone consulted for the project.

With special thanks to:

Dr. James Scouras for his thoughtful advice and key insights on nuclear war as a global catastrophic risk and for serving as an external reviewer of the report.

Matthew Gentzel for reviewing various drafts of the report, providing valuable feedback throughout the project, and serving as an external reviewer of the report.

Dr. James Acton, Conor Barnes, Tom Barnes, Patty-Jane Geller, Matt Lerner, Dr. Jeffrey Lewis, Ankit Panda, Dr. Andrew Reddie, and Carl Robichaud for reviewing earlier versions of the “Right of Boom” analysis in this document and for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Dr. Michael Horowitz for useful conversations and insights on these issues.

Dr. Michael Cassidy and Lara Mani for their explanation of volcanic aerosol chemistry and the potentially self-limiting effects of some climate phenomena, and Dr. Jon Reisner, Professor Alan Robock and Professor Brian Toon for their discussions on nuclear winter.

Dr. Jaime Yassif for many conversations on global catastrophic biological risks and general risk-reduction strategies.

Matt Lerner for extensive feedback, edits and guidance on the report.

Amber Dawn Ace for providing copy edits and helpful suggestions.

Dr. Zoë Ruhl for her support and invaluable insight.

Parts of this document were previously published as a Founders Pledge report on “Philanthropy to the Right of Boom,” which can be found here.

This report contains discussions of war and human suffering.

Executive Summary

Nuclear weapons are a global catastrophic risk; a nuclear war could kill untold millions, inflict horrific suffering on survivors, and derail human civilization as we know it. This report forms a guide for philanthropists who seek to mitigate this risk and maximize the counterfactual impact of their charitable donations. Specifically, the report seeks to guide funders entering this field in the wake of several challenges: the apparent collapse of post-Cold War arms control, the second year of the Russo-Ukrainian War, rising U.S.-China tensions, and a large funding shortfall for nuclear security. It mirrors many of the themes of Founders Pledge’s Guide to the Changing Landscape of High-Impact Climate Philanthropy, and is indebted to the insights in that document.[1]

The report’s analysis has four steps:[2]

Understanding key features of the landscape of nuclear philanthropy, with special attention to recent funding shortfalls.

Analyzing the structure of the problem, emphasizing the super-linearity of expected costs; not all nuclear wars are equal, and bigger nuclear wars could be disproportionately more damaging than smaller nuclear wars for both current generations and the long-term future.

Sketching guiding principles for nuclear philanthropy based on these ideas:

Prioritize minimizing expected global war damage;

Prioritize neglected strategies;

Multiply impact by shaping great power behavior;

Exercise leverage via policy advocacy;

Pursue a strategy of “robust diversification.

Exploring practical implications of these principles. The section briefly describes concrete projects that philanthropists can support. A conclusion enumerates key uncertainties and sketches a path forward for philanthropists

Overall, the report argues that deep uncertainty surrounds nuclear risk, that shaky assumptions underpin much of the conventional wisdom on nuclear war, and that effective philanthropists must learn to leverage their donations despite this uncertainty. Although the report reflects the input of a variety of experts, it is only one approach to the problem. We hope and expect to revise its conclusions as we encounter new evidence.

External Reviews

Founders Pledge’s research reports undergo several rounds of internal and external review. To provide the reader context for this report, we have asked two outside experts to briefly write up their impressions:

Reviewer 1: James Scouras

James Scouras is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and the former chief scientist of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency’s Advanced Systems and Concepts Office. Previously, he was program director for risk analysis at the Homeland Security Institute, held research positions at the Institute for Defense Analyses and the RAND Corporation, and lectured on nuclear policy in the University of Maryland’s General Honors Program. Among his publications are the book A New Nuclear Century: Strategic Stability and Arms Control, coauthored with Stephen Cimbala, and the edited volume On Assessing the Risk of Nuclear War. Dr. Scouras earned his PhD in physics from the University of Maryland.[3]

Scouras Review

Among the many and varied global catastrophic risks faced by humanity, nuclear war stands out for the combination of its potential immediacy, the horrific nature of its consequences, its long-term threat to civilization, and — most important of all — the fact that it has been created by humans and is subject to human interventions. With the end of the Cold War and the emerging multipolar nuclear future, a renaissance of creative, disciplined thinking is urgently needed and needs to be underwritten by both governmental and philanthropic organizations. Christian Ruhl’s Global Catastrophic Nuclear Risk: A Guide for Philanthropists lays a thoughtful intellectual foundation for justifying and focusing impactful philanthropy on reducing nuclear risks.

Most important, this paper challenges conventional wisdom in significant ways. In particular, it recommends emphasizing “right-of-boom” thinking. For too long the United States and its allies have put all their eggs in the deterrence basket. If the success of deterrence could be guaranteed, there would be no need to worry about the aftermath of its failure. But the complacency over the robustness of deterrence that has emerged from over three-fourths of a century without nuclear war may not serve us well in the future. Ominous trends in horizontal and vertical proliferation, the intensification and periodic eruption of enduring interstate disputes, and the never-ending advent of potentially destabilizing technologies all suggest we need to be better prepared for the possibility of nuclear war. Thus, we need to focus more on preventing small nuclear wars from escalating to large ones and recovering from all levels of nuclear war.

In addition, the paper is also innovative in its recommended focus on large nuclear wars that are disproportionately harmful compared to smaller nuclear wars. Large states can endure a small nuclear war, horrific though it will be. But it’s improbable that nuclear combatant states could survive a war that unleashed the arsenals of the major nuclear powers, and it is not clear how many centuries civilization would be thrown back and for how long. Thus, avoiding and recovering from large nuclear wars needs much greater focus in nuclear policy.

Finally, the paper identifies what is the most challenging problem in nuclear strategy: how to maintain deterrence and stability in the emerging tripolar nuclear world, with the United States, Russia, and China possessing comparably large nuclear arsenals. The fundamental problem is that the forces that underwrite deterrence against any single nuclear state would be inadequate to deter a coordinated attack by two peer adversaries. This concern could spark an arms race and/or motivate destabilizing force postures, launch decisions, and targeting doctrines. While the United States Strategic Command and policy organs of the US Department of Defense have recognized this challenge, a workable approach has not been identified, and any consensus is not on the horizon.

All these issues and many others identified in Ruhl’s paper require the sustained attention of the most knowledgeable, the most disciplined, and the most creative minds. Philanthropy can serve the critical roles of encouraging such minds to focus on this critical problem, fostering unconventional thinking, and challenging unimaginative, even wrongheaded and dangerous, government policies. Nuclear risk is far too important to leave to the generals.

Reviewer 2: Matthew Gentzel

Matthew Gentzel is a nuclear weapons policy program officer at Longview Philanthropy, where he co-leads Longview’s work on nuclear issues. His prior work spanned emerging technology threat and policy assessment, with a particular focus on how advancements in AI may shape the future of influence operations, nuclear strategy, and cyber attacks. He has worked as a policy researcher with OpenAI, as an analyst in the US Department of Defense’s Innovation Steering Group, and as a director of research and analysis at the US National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. Matthew holds an MA in strategic studies and international economics from Johns Hopkins SAIS and a BS in fire protection engineering from the University of Maryland.[4]

Gentzel Review

This guide is one of the most comprehensive approaches I’ve seen to reducing global catastrophic nuclear risk from a “big picture” perspective. While no document can cover every angle, it brings a variety of strategic considerations and thought tools together with sufficient depth to help philanthropists develop effective nuclear risk reduction strategies.

The extreme non-linearity of nuclear scenarios, the impact of different nuclear risk reduction interventions on other catastrophic threats such as bioweapons, and prioritization under extreme uncertainty are a few among many themes the guide covers. With examples such as the Cooperative Threat Reduction program, the guide also illustrates how philanthropists can drive extremely cost-effective risk reduction measures by bringing attention to neglected issues early and leveraging government resources.

One idea that may deserve future attention is how cultivating talent with broad awareness of crucial considerations can help uncover further opportunities both to prevent and to reduce the damage of nuclear war. While the prevention of nuclear use is relatively not neglected within the field, people with neglected expertise in positions of influence may still find traction. Similarly, talented individuals can help sort through interventions that initially appear to have an ambiguous track record: identifying the conditions that determine success with high quality analysis. Opportunities of these sorts often lie hidden by a variety of factors: ideological polarization, analytic siloing, misaligned bureaucratic incentives, efforts to manipulate risk perception, and the constraints of state secrecy. Training and elevating experts that can sort through these factors and the other considerations put forward in this guide could be a great investment.

Introduction: Deep Uncertainty

Key Points:

|

We know very little about nuclear war.[5] Despite countless books, articles, game-theoretic models, war games, and billions of dollars spent on understanding risk reduction, even well-respected experts and seasoned policymakers face fundamental and often unresolvable uncertainties about nuclear war.[6]

The world has had only one experience with the horrors of nuclear war through the atomic bombings of Japan in the summer of 1945. This distinguishes nuclear risk from some other global catastrophic risks, such as biological risks, where the history of natural pandemics can help analysts anchor risk estimates, including estimates of risk from unprecedented engineered pandemics. Moreover, uncertainty on nuclear war arises not just from complexity, but from sometimes being an optimization target for states; nuclear postures and policies are fundamentally about shaping risk perception, which complicates accurate risk estimation.[7] These factors lead to three fundamental uncertainties:

Uncertainty on the probabilities of nuclear wars[8]

Uncertainty on the consequences of nuclear wars

Uncertainty on effective risk-reduction measures

Together, these factors make up the fundamental components of risk (as a function of probability and consequence) and risk reduction. Such uncertainty can inspire apathy about risk reduction — in Cold War America, for example, popular jokes mocked attempts to reduce the consequences of nuclear war as futile: “What do you do when you see the flash? You put your head between your legs and kiss your ass goodbye.”[9] We need not take this fatalistic view. As explained throughout this report, philanthropists and policymakers can still prioritize interventions by understanding the general structure of the problem.

The following three sections disaggregate (1) uncertainty on probabilities, (2) uncertainty on consequences, and (3) uncertainty on risk reduction.

Uncertainty on Probabilities

First, how likely is nuclear war? We do not really know.[10] Ways of assessing this probability include:

Crowdsourced probabilistic forecasting;[11]

Elicited expert knowledge;[12]

Naïve base-rate forecasting;[13]

Subjective policymaker judgments;[14]

Probabilistic risk assessment based on near-misses and “teetering coin” analyses;[15]

and more, including the aggregation of multiple methods.

Aggregation of multiple forecasts can yield rough point estimates. Global priorities researcher Luisa Rodriguez, for example, has aggregated several estimates with the arithmetic mean of probabilities for an annualized probability of 1.1% of nuclear war, and a 0.38% probability of U.S.-Russia war.[16] A spreadsheet in the appendix adds further estimates to Rodriguez’s table and aggregates the estimates using the geometric mean of odds rather than the arithmetic mean of probabilities, yielding a 0.986% annual probability of nuclear war.[17] Point estimates can, however, obscure the magnitude of the uncertainty that surrounds these questions. Probability ranges can provide a more complete picture; Martin Hellman has given a rough order-of-magnitude estimate of around 1% per year in a publication by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), with a lower bound of 0.1% per year and an upper bound of 10% per year, based on reasoning about past crises and civilization’s survival with nuclear weapons so far.[18]

These estimates (including the estimates in this report) remain deeply flawed. There may be a problem of observer selection effects and the “anthropic shadow” at play with global catastrophic risks — if nuclear wars have the potential to extinguish civilizations in possible worlds where they occur, then civilizations that exist to observe their histories are unlikely to have a good sense of the true frequency of nuclear wars.[19] To the extent that many nuclear wars are likely not extinction risks per se — as discussed below — this is not a strong objection to probabilistic estimates.[20] Nonetheless, like the winners of a coin-flipping contest, we ought not assume that our good luck necessarily tells us much about the coin or about our coin-flipping skills.[21] Moreover, the estimates about the probability of the outbreak of nuclear war obscure important distinctions about different kinds of nuclear war and about escalation probability curves.[22] More detailed analyses simply do not exist and we ought to be suspicious of highly complex and formalized models of risk insofar as they are not grounded on reference class forecasting or other empirical bases. It may be best to follow a dictum of net assessment: “model simple and think complex.”[23]

Uncertainty on Consequences

Second, what are the effects of nuclear war? Again, we do not really know.[24] In the aftermath of the atomic bombings of Japan, medical personnel collected information documenting the horrors of the nuclear weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki: blast damage, flash burns, blindness, fire, acute radiation poisoning, and long-term health effects.[25] Nuclear testing later revealed other issues. Atomic scientists soon realized that nuclear fallout — radioactive material that is catapulted into the air and spread over the earth’s surface during some nuclear explosions — could present a serious problem, as it did when radioactive ash rained on the tuna fishing boat Lucky Dragon after a 1954 U.S. nuclear test and poisoned the crew.[26] Similarly, the 1962 Starfish Prime test of a high-altitude nuclear detonation created an unexpectedly large electro-magnetic pulse (EMP) effect, revealing yet another danger from nuclear weapons for a modern civilization that relies on EMP-vulnerable critical infrastructures.[27]

Nuclear testing did produce data on the observable physical effects of nuclear weapons, creating well-characterized understandings of blast radii and yields.[28] As the scholar of nuclear risk Dr. James Scouras points out, however, our knowledge about nuclear weapons is biased towards these easily-observable and -measurable physical effects.[29] One of the most significant effects of nuclear war is “nuclear winter”: the climate effects of soot in the Earth’s atmosphere following firestorms after a nuclear war. This remains poorly understood. As discussed below in The Non-Linearity of War Effects, several aspects of nuclear winter research — including uncertainties about black carbon release and transportation into the stratosphere — lead to extreme uncertainty surrounding possible climate effects.

Beyond nuclear winter, the societal consequences of nuclear war are even more uncertain. How would widespread grief and post-traumatic stress disorder affect recovery efforts? How would agricultural practices change in response to nuclear winter? Would there be food hoarding or global cooperation to share limited resources and avert mass starvation? Could liberal democracies withstand the challenges of major nuclear war better or worse than autocracies? Would nuclear use erode norms around other weapons of mass destruction, such as strategic biological weapons? Would it hasten the development and unsafe deployment of risky emerging technologies? At what point would global civilization collapse? How likely is recovery after a civilizational collapse? How likely is a recovery with good values after a civilizational collapse? Would a totalitarian hegemon emerge in the aftermath of nuclear war? Is total human extinction likely?

Again, it is possible to build complex models to try to answer these questions, and some researchers have made admirable efforts to understand civilizational collapse, but fundamentally we are speculating on the answers to these questions.[30]

Uncertainty on Risk Reduction

[This section is adapted from a previous Founders Pledge report on “Philanthropy to the Right of Boom.” Readers familiar with that document may wish to skip to the section on Reasoning under Uncertainty.]

Third, what can we do about this risk? Once again, we do not really know. If we care about preventing all-out war between the United States and Russia, for example, what should we do? Should we fund track II (i.e. non-governmental) diplomatic dialogues to discuss the future of arms control after the demise of the New START agreement? Should we focus on understanding the effects of applications of new technologies such as artificial intelligence on strategic stability? Should we promote civil defense and agricultural resilience to prepare for worst case scenarios? Should we fund grassroots campaigns for nuclear arms control and disarmament?

Philanthropists may have some considerations that bear on these questions. For example, funders may believe that nuclear disarmament is an intractable goal, given the political and military realities of the world; or that the world currently represents one of the more stable distributions of capabilities. More fundamentally, however, we continue to have a poor understanding of the sources of nuclear risk, its probability, and its consequences.[31] Unlike other issue areas where the mechanism of change is clearer, scholars of nuclear war disagree on fundamental issues, such as whether a “no first-use” or “sole purpose” declaratory policy would be desirable.[32]

This uncertainty is not just the uncertainty of any non-expert funder, that could be resolved by learning more about the field. Subject-matter experts’ theories remain untested and often untestable.[33] Historical accounts of states’ behavior can provide some evidence, but these studies face the problem of the counterfactual. Probabilistic forecasting can help aggregate the “wisdom of the crowd” but, in questions about low-probability, high-consequence risks, these methods lack the objective scoring metrics that make them so powerful in other contexts; the data to resolve forecasts either do not exist or are too few.[34] Similarly, new attempts in international relations to construct “experimental wargames” appear promising, but also run into the problem of “ecological validity” — how well do the games actually represent the reality they purport to simulate?[35]

The problem, once again, is that the world has very limited experience with nuclear war and it is unclear how this experience translates to present challenges. Thus there is little opportunity for falsification of theories and there are limited reference classes and base rates for understanding nuclear war, the likelihood of escalation, and the consequences of different kinds of nuclear war. This allows for a wide range of plausible viewpoints and possible interventions for philanthropists.

These deep uncertainties also mean that we do not know much about what “safe” interventions might be. Later sections of this report suggest that interventions “right of boom” — after first nuclear use — may be high-impact funding opportunities: for example, developing a deeper understanding of escalation management. A common objection to this is that such interventions are dangerous because they may make war appear “winnable” and may thus raise the probability of nuclear war even if they mitigate the consequences of such a war. This is a fair concern, and one that ought to be studied further (by funding more policy-relevant right-of-boom research).

It is important to note, however, that philanthropists face similarly high uncertainty about the potential downsides of more ideologically palatable interventions, such as disarmament. At first glance, disarmament appears obviously good. The current distribution of capabilities, however, may represent one of the more stable configurations and possible worlds.[36] There has been no nuclear war since 1945, slow nuclear weapons proliferation, minimum deterrence arsenals in many nuclear states, restraint on many kinds of strategic weapons systems, and no all-out race on arsenal size for several decades.[37]

Whether nuclear deterrence has contributed to the “Long Peace” of the 20th and 21st centuries — and whether the Long Peace is a statistically meaningful phenomenon — is an issue under debate, but is a relevant factor for weighing the benefits of disarmament.[38] Smaller arsenals may, moreover, change targeting practices such that the expected cost increases — some arguments for “minimum deterrents” rely on the targeting of cities, civilian populations, and industrial centers, rather than counterforce targeting.[39] The key point is that uncertainty abounds on all risk reduction measures, including about the sign of interventions (i.e. whether it is net good or bad). This is discussed in greater detail below (“Is Disarmament Obviously Net-Positive?”)

Reasoning Under Uncertainty: Impact Multipliers and Crucial Considerations

High uncertainty on probabilities, consequences, and risk reduction is not the same as cluelessness. As explained in Founders Pledge’s Guide to the Changing Landscape of High-Impact Climate Philanthropy, “Even when we deal with large uncertainties, this does not mean we cannot make statements about the relative promise of different strategies and the likelihood that they will be highly impactful.”[40]

As explained in the next two sections, there are some observable features of the structure of nuclear risk and the allocation of philanthropic funds that allow philanthropists to identify crucial considerations for strategic giving and develop “impact multipliers.”

[The rest of this section is adapted from Founders Pledge’s report on “Philanthropy to the Right of Boom.” Readers familiar with this document may wish to skip to the next section, The Changing Landscape of Nuclear Risk Reduction.]

In this context, the term “impact multipliers” refers to features of the world that make one funding opportunity relatively more effective than another.[41] Stacking these multipliers makes effectiveness a “conjunction of multipliers;” understanding this conjunction can in turn help guide philanthropists seeking to maximize their impact under high uncertainty.[42] Doing this may not allow us to understand absolute cost-effectiveness (in terms of lives saved per dollar), but does allow us to understand relative cost-effectiveness, and thereby rank and identify the most effective interventions.[43]

Not all impact multipliers are created equal, however. To systematically engage in effective giving, philanthropists must understand the largest impact multipliers — “critical multipliers”. These are features that most dramatically cleave more effective interventions from less effective interventions. In global health and development, for example, one critical multiplier is simply to focus on the world’s poorest people. Because of large inequalities in wealth and the decreasing marginal utility of money, helping people living in extreme poverty rather than richer people in the Global North is a critical multiplier that winnows the field of possible interventions more than many other possible multipliers.

Additional considerations — the prevalence of mosquito-borne illnesses, the low cost and scalability of bednet distribution, and more — ultimately point philanthropists in global health and development to one of the most effective interventions to reduce suffering in the near term: funding the distribution of insecticide-treated bednets.[44] This report represents an attempt to identify defensible critical multipliers in nuclear philanthropy,[45] and potentially to move one step closer to finding “the nuclear equivalent of mosquito nets.”[46]

There are many potential impact multipliers in nuclear philanthropy. For example, as explained below, focusing on states with larger nuclear arsenals is likely to be more impactful than focusing on nuclear terrorism. Nuclear terrorism would be horrific and a single attack in a city (e.g. with a dirty bomb) could kill thousands of people, injure many more, and cause long-lasting damage to the physical and mental health of millions.[47] All-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia, however, would be many times worse. Hundreds of millions of people could die from the direct effects of a war. If we believe nuclear winter modeling, moreover, there may be many more deaths from climate effects and famine than from the blast and other direct impacts of the bombs.[48] In the worst case, civilization could collapse. Simplifying these effects, suppose for the sake of argument that a nuclear terrorist attack could kill 100,000 people, and an all-out nuclear war could kill 1 billion people. All else equal, in this scenario it would be 10,000 times more effective to focus on preventing all-out war than to focus on nuclear terrorism.[49]

Generalizing this pattern, philanthropists ought to prioritize the largest nuclear wars (again, all else equal) when thinking about additional resources at the margin. This can be operationalized with real numbers — nuclear arsenal size, military spending, and other measures can serve as proxy variables for the severity of nuclear war, yielding rough multipliers.[50] These measures are imperfect proxies — nuclear weapons can be viewed as a way to “offset” costly conventional military spending, as in the Eisenhower administration’s First Offset strategy, which emphasized more “bang for the buck” — and should not be used in isolation.[51] This could lead philanthropists to prioritize risk mitigation around adversarial relationships between the world’s “great powers.” Similarly, because risk is a function of probability and consequence, philanthropists who aspire to be most effective can prioritize the nuclear relationships that are most likely to lead to war (and, further, those that are most likely to draw in larger powers).

These impact multipliers already yield useful conclusions. They suggest a focus on the behavior of major nuclear-armed states and, within this, a focus on preventing the largest wars. This may differ substantially from the approach of some traditional philanthropic actors working on nuclear security. We expand on these points in greater detail below.

The next section discusses the funding patterns of these actors in light of the changing threat landscape of the so-called “New Nuclear Age.” This discussion informs the search for impact multipliers in the sections that follow later in the report.

Questions for Further Investigation

|

The Changing Landscape of Nuclear Risk Reduction

Key Points:

|

This section outlines key features of the landscape of nuclear risk and nuclear philanthropy. In short, a large philanthropic funding gap has opened at an inconvenient time. Structural features of the world — including heightened great power competition, a multipolar nuclear order, the breakdown of traditional arms control, and rapid advances in emerging technologies — may increase nuclear risk, or at least increase uncertainty about the magnitude of that risk.

At the same time, recent large-scale funding shortfalls in nuclear philanthropy and in catastrophic risk reduction broadly have left the field scrambling for money. On the one hand, this is highly unfortunate, especially in light of the potentially increased risk during the Russo-Ukrainian war (ongoing as of this writing in 2023). On the other hand, it presents a potentially high-leverage opportunity, as grantees may be more receptive to new ideas and approaches.

The “New Nuclear Age”?

Subject-matter experts in nuclear security so often refer to a “new nuclear age” that the term has become cliché.[52] Usually, this phrase refers to an interconnected set of observations about international security in the 2020s. The first is the idea of a “multipolar nuclear order.” As described in the recent book The Fragile Balance of Terror,

“[T]he emergence of multiple nuclear states [since the Cold War] makes balances of power more complex and deterrence relationships more uncertain. Our theories and understanding derived from the Cold War bipolar nuclear competition leave us ill-equipped to handle the daunting challenges of this new nuclear age.”[53]

The question of whether more nuclear states make the world more or less safe does not, however, have an obvious answer, and there are arguments that multipolar deterrence is more stable.[54] Once again, philanthropists ought to be epistemically humble about what they can and cannot know about nuclear risk. We should remember, moreover, that most nuclear weapons states represent a tiny fraction of the world’s arsenals. The United States and Russia continue to dominate these measures:

Source: Our World in Data, using data from Federation of American Scientists.

These reductions are even more significant than they look by warhead count; weapon yields were also decreasing dramatically with the removal of multi-megaton warheads from arsenals.[55] In general, assessing both absolute and relative nuclear capabilities is far more complicated than mere warhead counts can illustrate, with additional considerations including not only yield but also reliability.[56]

One emerging exception to the dominance of the United States and Russia is China, the third-largest nuclear power and one of the United States’s main strategic rivals. In late 2022, the U.S. Department of Defense suggested in its China Military Power Report that “If China continues the pace of its nuclear expansion, it will likely field a stockpile of about 1500 warheads by its 2035 timeline.”[57] If we take this estimate at face value, and for simplicity assume that other stockpiles will remain unchanged, China’s arsenal is still small compared to U.S.-U.S.S.R. Cold War heights, but becomes an appreciable fraction of the world total by 2035:

Source: Author’s visualizations based on Our World in Data illustration (above), combining Our World in Data dataset and the U.S. Department of Defense China Military Power Report projection (2022).

Warhead number is not the only salient feature of China’s changing nuclear ambitions.[58] Additional developments include building out a nuclear triad, testing a “fractional orbital bombardment system” with a hypersonic glide vehicle in 2021 (though China denies this was the purpose of the test in question), building 300 new missile silos, and potentially even changing fundamental parts of Chinese nuclear posture and policy.[59] In short, China’s nuclear arsenal and policy are changing drastically and quickly.

The Three Body Problem

The features discussed above lead to another fact of the “new nuclear age” — renewed great power competition and the problem of “three-way deterrence” between Russia, China, and the United States. The broader problem of conflict between major military powers is discussed in Founders Pledge’s report on Great Power Conflict. U.S. national security strategy documents also emphasize great power competition, but Founders Pledge’s focus on the issue stems from a desire to prevent human suffering and catastrophe globally, not from a pursuit of national interests. The 2022 National Defense Strategy lists great power competition as part of several “top-level priorities”: “Defending the homeland, paced to the growing multi-domain threat posed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC)” and “Deterring aggression, while being prepared to prevail in conflict when necessary – prioritizing the PRC challenge in the Indo-Pacific region, then the Russia challenge in Europe.”[60] Similarly, the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review singles out the PRC as a primary factor in U.S. evaluation of nuclear deterrence:

“The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is the overall pacing challenge for U.S. defense planning and a growing factor in evaluating our nuclear deterrent. The PRC has embarked on an ambitious expansion, modernization, and diversification of its nuclear forces and established a nascent nuclear triad. The PRC likely intends to possess at least 1,000 deliverable warheads by the end of the decade.”[61]

Competition with a near-peer competitor (the USSR) drove U.S. nuclear policy during the Cold War, too, but the challenge of “three-way deterrence” with two near-peer competitors is new.[62] Cold War game-theoretic models were designed largely with one major adversary in mind, but the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review makes it clear that the U.S. now believes it will need to deter two major nuclear powers.[63] Some of these issues are structural: negotiations become more complex when more than two parties must agree. Other issues may relate to targeting policy: new and challenging considerations arise over counter-force targeting and what kinds of deterrence regimes appear most desirable to states in three-way deterrence.[64] Not all changes are necessarily destabilizing:[65]

“Truels” (i.e., single-shot duels between three players) may further disincentivize first strikes, depending on the balance of capabilities;

The existence of an additional large nuclear power may make a single coercive Russian nuclear monopoly less likely in certain catastrophic scenarios;

These dynamics may make it easier in some situations for a third party to de-escalate crises between the other two.

Again, we do not know how these considerations will stack up; uncertainty is high. For these reasons, leaders of U.S. Strategic Command have expressed concern about what Admiral Charles Richards has compared to the “three-body problem” in physics, stating that “I’m not sure what strategic stability looks like in a three-party world,” that STRATCOM has been “furiously” working on renewed deterrence theory, and that he remains deeply pessimistic despite this work: “There are exactly zero stable [...] three-body orbital regimes.”[66]

Emerging Technologies

A third feature of the “New Nuclear Age” is the impact of new and emerging technologies on the nuclear balance. Not all of these developments are equally concerning, and the threat of some technologies has been exaggerated for political purposes. Discussion of the so-called “hypersonic arms race,” for example, seems to misunderstand basic facts about the state of missile defense technology — some of it, like homeland missile defense, is in its infancy — and about the purpose of U.S. homeland missile defenses (they are designed with North Korea and Iran, not China and Russia, in mind).[67] (These considerations may be different for regional systems like THAAD and Aegis, where the effects of hypersonics may be more important.[68])

Other new technologies, however, are more concerning. Among these are applications of machine learning technologies to various systems, both nuclear and conventional, and the instability that this may create. Founders Pledge’s 2022 report Autonomous Weapons Systems and Military AI discusses these risks in detail under the section titled “Pathways to Risk.” The pathways to nuclear risk are outlined in the figure below, adapted from the same report:

Autonomy in Weapon Systems and Nuclear Risk

Source: Adapted from Founders Pledge report, Autonomous Weapon Systems and Military AI (“Pathways to Risk”). N.B. This merely purports to represent possible, not probable, pathways.

The list of potential new and emerging technologies that may affect strategic stability is long, and the signs of their effects (whether they will be positive or negative contributors to stability) are often unclear.[69] It is possible that applications of AI in nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) — managed appropriately — can help improve threat assessment, decrease accident risk, and lengthen decision windows in ways that reduce risk overall. One potentially dangerous application of predictive machine learning systems is for “strategic warning” of nuclear attack.[70] The Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms no longer includes a definition of strategic warning, but used to define it as “a notification that enemy-initiated hostilities may be imminent” and defined “tactical warning” in contrast as “a notification that the enemy has initiated hostilities.”[71] The incentives to adopt such systems are clear; if it provides early warning of an adversary’s intended action, it provides early opportunity to prepare for that action. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union RYaN program (short for Raketno-Yadernoe Napadenie, or Nuclear Missile Attack) sought to quantify risk based on an aggregate of supposed strategic warning indicators dreamed up by Soviet leadership (such as “the amount of blood held in Western blood banks and the location of Western leaders”).[72] Because there have been no examples of nuclear surprise attacks to train on, however, poorly implemented modern AI-enabled RYaN programs may be biased and increase the risk of war by giving false warnings.[73] Again, however, analysts ought to be epistemically humble about these issues; just because they could increase the risk of war does not mean that they will.

There are large uncertainties and new moving parts to this age, such that nuclear risk subjectively feels high. On February 21, 2023, Vladimir Putin announced that Russia would suspend its participation in the New START arms control agreement between Russia and the United States.[74] The extended agreement was set to expire in 2026, already creating an uncertain future for strategic arms control.[75]

Whether the risk is — as the 2023 state of the “Doomsday Clock” at “90 seconds to midnight” implies — as high as it was at the height of the Cold War, when fewer risk reduction measures were in place and U.S. and Russian arsenals were much larger, is unclear.[76] At the same time, however, current philanthropic funding for nuclear risk reduction is unusually low, creating a danger of neglect just as the world is changing; the next section discusses this funding shortfall.

Funding Shortfalls: MacArthur and FTX

In 2022, the Founders Pledge Patient Philanthropy Fund made a grant in support of an analysis by Alex Toma of the Peace and Security Funders Group on The Changing Landscape of Nuclear Security Philanthropy: Risks and Opportunities in the Current Moment. The analysis can be found here.

To summarize the key points of the report:

In 2021, the MacArthur Foundation announced that it would withdraw its support of nuclear security grantmaking via a $30 million capstone project distributed over multiple recipients — final funds will be disbursed in 2023.[77]

MacArthur was the largest private funder of nuclear security work. Its withdrawal was described as “a big blow” to arms control.[78]

This funding gap may be partially filled by the entry of new funders.

Not all of this is bad, and new funders may have the opportunity to reshape the field in beneficial ways.

Since the publication of Toma’s analysis, the behavior of another funder has changed this picture. In late 2022, various corporate and philanthropic entities associated with FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried collapsed and filed for bankruptcy. Grants committed by associated entities were reportedly not distributed and may be at risk of clawback in bankruptcy court.[79] Archived pages of the now-defunct FTX Foundation’s Future Fund’s website show that one of the single largest grants was made in part to support nuclear grantmaking, and that global catastrophic risks and great power conflict would have been major areas of focus for future grants.[80] The effect of the FTX collapse on this grantmaking remains uncertain, but it appears to have shrunk the pool of possible funding for nuclear security significantly.[81]

Without new funders, the state of philanthropic funding for nuclear security looks even more dire than it did in early 2022. On average, MacArthur made grants of around $15 million per year between 2014 and 2020. Total philanthropic nuclear security funding stood at about $47 million per year, such that the field faces a 32% reduction in funding.[82] The centrality of MacArthur to the field is visualized in Toma’s report — all the organizations in MacArthur’s “orbit” are at risk of running out of funding:

Source: Alex Toma, The Changing Landscape of Nuclear Security Philanthropy, from Peace and Security Funding Index visualization.

Bad Timing, High Leverage

In its coverage of the MacArthur withdrawal, Vox called this the “worst possible time” for a shortfall in nuclear security philanthropy, in light of the Russo-Ukrainian War.[83] While it is indeed bad timing, this moment may also represent a time of unusually high leverage over the field. As Toma pointed out, “amidst the turmoil of this major funder leaving, there is opportunity to rethink and reshape the field.”[84] This leverage is even higher in the wake of the FTX collapse. The field may be more open to a reassessment of strategic priorities than it otherwise would be. The next section outlines structural features of the problem of nuclear risk that can guide impact-oriented philanthropists in developing these priorities.

Questions for Further Investigation

|

The Structure of the Proble

Key Points:

|

The previous section framed the current moment in nuclear risk and philanthropic support of risk-reduction measures. To summarize:

There are large uncertainties about the magnitude of future nuclear risk, especially around Chinese intentions and nuclear ambitions.

There has been a major funding shortfall, such that nuclear issues are unusually neglected.

This may represent a moment of high philanthropic leverage over the field.

This section discusses key facts about the problem structure of nuclear risk. The aim is to reason from simple first principles, rather than try to build complex and untestable models about deterrence and arms control, and should be read in the context of philanthropic giving. Several key facts about the structure of the problem emerge:

Nuclear wars are not created equal — all else equal, if a given grant prevents a large nuclear war it is more cost effective than if it prevents a small nuclear war.

There is a superlinear relationship between war size and global war costs (in human wellbeing) — larger wars are disproportionately worse than smaller wars.

Funders, experts, and decision-makers face deep uncertainty about the effectiveness of interventions — we often simply do not know what would work best, and have no way of finding out.

Accidents happen — the problems of nuclear crisis management and escalation control are likely here to stay, and cannot be ignored.

What comes down can go back up — Cold War arsenal reductions are not guaranteed to be “sticky,” and some trends suggest that states are interested in arming; the magnitude of nuclear risk could increase significantly in the near future.

Nuclear Wars Are Not Created Equal

Some nuclear wars — such as an all-out thermonuclear war between two states with arsenals the size of the Cold War United States and Russia — could be civilization-ending events, especially but not only if we give credence to high estimates of the probability and severity of the climate effects of nuclear winter (discussed below). On the other hand, the Second World War was technically a nuclear war, but that nuclear use was not a civilization-ending event, despite its horrific consequences for the inhabitants of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[85]

There is, in short, a spectrum of possible nuclear wars. At the lowest end of this spectrum (with a questionable use of the word “war”) is dirty-bomb terrorism, whose direct effects are highly limited, and which is designed to incite fear in a population, rather than to maximize damage and death. At the highest end of the spectrum exist possible futures (discussed below) where many states deploy extremely large arsenals and a global conflagration could kill billions of people. Indeed, some early Cold War strategists believed that the distinction between “limited” and “all-out” nuclear war is more salient than the distinction between “nuclear” and “non-nuclear” war.[86]

This fact matters because philanthropists have limited resources and must therefore prioritize both between and within issue areas. Funders therefore need to decide where to focus their efforts; “preventing the use of nuclear weapons” may be too broad a concept to guide high-impact giving. Understanding this fact allows us to then make a conclusion; all else equal, it is more cost-effective if a given grant prevents large nuclear wars than if it prevents small nuclear wars.

The following section discusses the implications of this in greater detail; the highly non-linear relationship of war size to war costs, especially when considering long-term effects, only underscores the importance of focusing on the largest wars.[87]

The Non-Linearity of War Effects

A key feature of nuclear war is that the risk is non-linear. In large part due to climate dynamics, threshold effects, and the possibility of societal collapse, all-out nuclear wars are disproportionately worse than highly limited nuclear wars. We can demonstrate this nonlinearity by comparing the effects of the bomb used on Hiroshima in 1945 to the effects of 100 such bombs used in a hypothetical conflict between India and Pakistan. The best available estimates suggest that about 70,000 to 140,000 people died in Hiroshima alone.[88] Two such bombs likely would cause the deaths of 140,000 to 280,000 people. A naive linear extrapolation of this would suggest that 100 times as many bombs would lead to 100 times as many deaths — 7,000,000 to 14,000,000. As we will see, however, this linear extrapolation misses key effects that multiply the damage of larger nuclear wars. The next sections explain the various features of nuclear war that, although their magnitude is uncertain, stack together to create an approximately super-linear relationship between war size and war cost (though this relationship may break down at extreme war sizes, as discussed below in the section titled “Overkill and ‘Making the Rubble Bounce’”).

Nuclear Winter

The deaths from a war fought with 100 Hiroshima-sized weapons may be more than an order of magnitude higher than a naive linear extrapolation would suggest.This is in large part due to “nuclear winter” — the hypothesized climate effects that would result from soot being injected into the atmosphere during a nuclear exchange. This could block out sunlight, resulting in cooler temperatures, which would make it harder to grow food. The literature on nuclear winter is relatively small, and estimates of the severity of potential cooling effects vary widely. We have collected a table of several influential studies in Appendix 3. After some initial interest in nuclear winter in the 1980s, there was a lull in research, followed by a second wave of nuclear winter studies in the 2000s and 2010s. Several of the studies in this second wave, led by Professors Alan Robock and Brian Toon, among others, focused on one hypothetical scenario: a war between India and Pakistan involving 100 15-kiloton warheads. This scenario is therefore among the best-studied.[89] Estimates of cooling in these studies range widely, from very limited cooling mostly in polar regions, to global mean cooling of nearly 2ºC.[90] Xia et al. (2022) estimated that such a war would lead to 27 million direct deaths (from the impact of the bombs), and could lead to the starvation of over 250 million people due to climate effects.[91]

Reisner et al. (2018) provide one detailed critique of Robock et al.’s research. Many studies with high death toll estimates assume that human behavior will not adapt to new agricultural conditions.[92] Several studies also do not account for the interaction of climate change with nuclear winter — a 2ºC cooling via soot injection in a 2ºC-warming world could be treated analogously to geoengineering or “Solar Radiation Management” (SRM) via stratospheric aerosol injection, with effects on crop yields highly uncertain.[93] Some of the SRM literature suggests that volcanic cooling (analogous to nuclear war-induced cooling) may have only a small net negative impact on crop yields, or even a positive impact when accounting for climate change. Pongratz et al. estimated that SRM in a high (2X) CO2 environment would actually increase global crop yield because it would decrease the stress of high temperatures while retaining CO2 fertilization benefits.[94] A 2018 analysis in Nature suggested that mid-21st-century cooling of 0.88ºC as a result of solar radiation management would decrease heat stress on plants but have no discernible effect on maize, soy, rice, and wheat yields when accounting for the decrease in sunlight (i.e., damages from scattered sunlight and benefits from slight cooling may even out in some scenarios).[95] Nonetheless, we should not be sanguine about the possible negative effects of sudden cooling, such as frost disrupting normal crop growth.

However, even if a skeptic believed that these estimates were twice as high as they should be, they would be left with the possibility of more than 100 million people starving. This shows that deaths increase non-linearly. Again, 70,000 to 140,000 people died in Hiroshima alone; two such bombs likely would kill 140,000 to 280,000 people, but 100 times as many bombs would kill more than 100 times as many people. Reasoning in orders of magnitude, using the death tolls calculated in the nuclear winter literature suggests that moving from 1 to 2 15kt-sized nuclear explosions multiplies the deaths by a factor of 2, whereas moving from 1 to 100 15kt-sized nuclear explosions multiplies the deaths by a factor of 1,000.

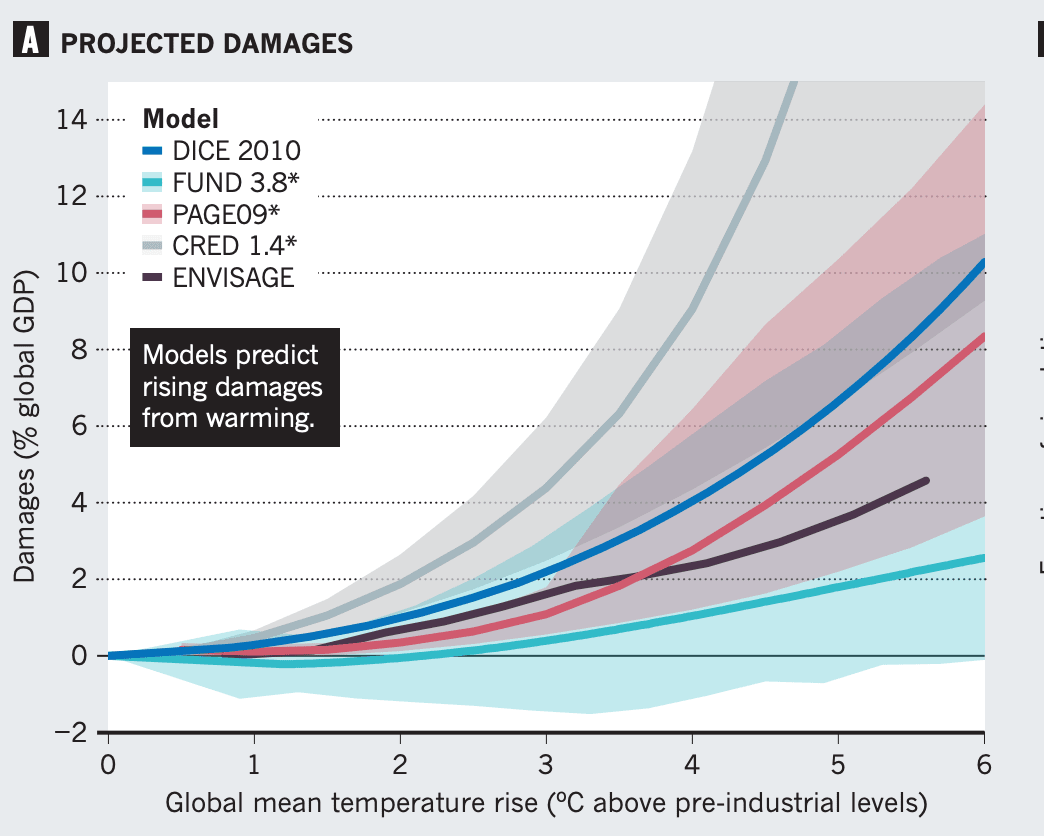

Moreover, one implication of the possibility of nuclear war-induced global cooling is that there may be threshold effects roughly symmetrical to those of global warming. For instance, animals and crops domesticated during the Holocene epoch have certain temperature ranges, within which agriculture can thrive.[96] Crops can only withstand so many days of early frost at certain temperature floors (or days of extreme heat at certain temperature ceilings); as global climate change shifts the normal distribution of the number of such days, the mass of the distribution that passes these “thresholds” increases non-linearly.[97] Similar thresholds may exist for civilization as a whole — for example, a society may be able to handle only a certain amount of refugees before its institutions begin to crumble (e.g. due to xenophobic authoritarian backlash). Threshold effects are partly what drive the highly non-linear effects of climate change that are well-established in the literature on global warming:[98]

Source: Richard L. Revesz et al., “Global Warming: Improve Economic Models of Climate Change,” Nature 508, no. 7495 (April 2014): 173–75, https://doi.org/10.1038/508173a.

There are further uncertainties in the nuclear winter literature. One crucial consideration, for example, is how much of the black carbon that is produced from fires actually reaches the stratosphere; factors like time of year, cloud cover, and precipitation all affect this question.[99] Targeting plans also affect the amount of smoke produced, and it is generally agreed that military targets would produce less and different smoke than civilian city targets with higher fuel loads.[100] We discussed this targeting effect with Professors Robock and Toon, who agreed that targeting is a crucial consideration and that in theory targeting remote missile silos in desert-like areas (where China’s missile fields are situated) would produce less smoke and therefore a less severe effect.[101] However, while publicly-stated U.S. targeting policy explicitly rejects civilian targeting, some military targets may necessarily be located close to civilian areas, and targeting policies may evolve in the course of a nuclear war, such that it is highly unclear where nuclear weapons would actually be used in a war.[102] Uncertainty on Russian and Chinese nuclear targeting is even larger.[103] Complicating the picture even further, the burning of massive fuel loads in a large nuclear war could release greenhouse gasses that lead to increased warming over longer time scales.[104]

In short, we simply don’t know the answers to some key questions, including how much soot different kinds of nuclear war would release into the atmosphere and how much of this soot would reach the stratosphere. Nonetheless, there is some agreement that can be gleaned from the literature: very small nuclear wars would affect the climate much less than very large nuclear wars, and perhaps not at all.

This general pattern applies not just to temperature change, but to other important factors that affect agricultural production, as shown in figure 1. of Xia et al.’s 2022 Nature Food paper:[105]

Source: “Climatic impacts by year after different nuclear war soot injections” in Xia et al., “Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection,” Nature Food. “Tg.” refers to teragrams of black carbon; again, the exact type of nuclear war that would inject such amounts of soot is disputed. Note that higher soot injection leads to greater climatic effects.

Therefore, while we don’t know much about the probability distributions of nuclear winter, we can draw a stylized but useful conclusion from this literature: not all nuclear wars would lead to nuclear winter, but larger wars are more likely to lead to severe climate change, and threshold effects amplify the superlinear cost of this.[106] Once again, this may appear obvious, but it has large implications for the prioritization of marginal philanthropic resources.

Civilizational Collapse

Taking a longer-term perspective on humanity’s future, the non-linearity of the war size-to-cost relationship becomes even more extreme. The starvation of 100 million people would be a humanitarian catastrophe and one of the worst events to befall humanity thus far, killing 1.25% of the world’s population. (For comparison, between 17.4 million and 50 million people died in the 1918 “Spanish Flu” pandemic, one of the worst pandemics in recent history, representing between 0.95% and 5.4% of the population at the time.[107])

These are horrific numbers to contemplate. An even worse — and qualitatively different — picture emerges, however, when we consider the largest possible nuclear wars, such as an all-out U.S.-Russia nuclear exchange, and the possibility that such wars could lead to the collapse of global civilization.

As discussed above, experts disagree on the severity of global cooling caused by such a war. As far as we are aware, none of the scientists involved in nuclear winter modeling claim that direct extinction is likely even from severe nuclear winter. In the 1980s, some scientists suggested that a U.S.-Russia exchange (with more and bigger weapons than are available today) could trigger apocalyptic cooling that would bring land temperatures as low as −15ºC to −25ºC, worse than the coldest parts of the last Ice Age.[108] Today, no scholars of nuclear winter suggest such extreme effects, in part due to updated models, and in part due to reduced arsenals. Indeed, one common analogy for nuclear winter is the Toba Eruption approximately 74,000 years ago.[109] This is a common case study for solar radiation disruption and climate shocks, as it was the largest volcanic eruption in the Quaternary period (the last 2.5 Million years).[110] The Toba “super-eruption” was at one point theorized to have caused a near-extinction event, but more recent estimates conclude that there was no volcanic winter-induced evolutionary bottleneck, and humanity was likely not close to extinction (note, however, that this eruption was before the Agricultural Revolution, and agricultural civilization may be vulnerable in different ways).[111] Although the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, the very idea of “volcanic winter” was based on estimates from the 1990s that were too high by 1-2 orders of magnitude, according to a recent review of the evidence since then.[112] This matters because the idea of “nuclear winter” is analogous in some respects (though importantly dis-analogous in others) to “volcanic winter,” and it should update our beliefs about the theory that either large volcanic eruptions or nuclear war could directly cause extinction events.[113]

Nonetheless, a U.S.-Russia nuclear war (or a future U.S.-China nuclear war with bigger arsenals) could in theory precipitate civilizational collapse; as discussed above, our uncertainty on nuclear winter effects ought to be very large, and this uncertainty goes both ways. The deaths of hundreds of millions to billions of people in such a cataclysm is an unprecedented event, and we do not know how civilization would respond, how robust and resilient the systems-of-systems underpinning global civilization are, and whether the survivors of such a catastrophe could rebuild. Modern civilization relies on a large human population and complex large-scale infrastructure. Because larger nuclear wars are more likely to lead to severe infrastructure damage and mass starvation than smaller nuclear wars, we can draw another simplified conclusion: not all nuclear wars would lead to civilizational collapse, but the largest wars will likely increase the probability of collapse.

Existential Catastrophe beyond Extinction

Scholars of nuclear winter agree that global cooling would probably not directly cause human extinction, and that there is high uncertainty around the estimates of the length and severity of the associated cooling. Again, even the scientists who have produced the most extreme estimates of nuclear winter effects do not claim that it would constitute an extinction event per se (except insofar as it might precipitate civilizational collapse).[114] A recent report by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory explains, “While some nuclear disarmament advocates promote the idea that nuclear winter is an extinction threat, and the general public is probably confused to the extent it is not disinterested, few scientists seem to consider it an extinction threat.”[115] This was possibly even the case with the far larger arsenals at the height of the Cold War.[116]

The apparent low probability of direct extinction via nuclear winter has caused some analysts of existential risks to discount the threat of nuclear war.[117] The Existential Risk Observatory, for example, writes “complete extinction because of direct effects of nuclear war, although very important for non-existential reasons, is not the main existential threat.”[118] A similar view is expressed in many other analyses, sometimes accompanied by low subjective point estimates of extinction risk.[119] These views, though diverse, are based on three types of consideration. First, considerations like the expiration dates of some critical resources lead some analysts to optimistic conclusions about post-collapse worlds; there may be a “grace period” where resources last long enough to support efforts to restart civilization.[120] Second, mechanistic views of a post-collapse society suggest quasi-Malthusian “collapse equilibria,” where populations are balanced against available resources.[121] Third, statistical arguments about uncorrelated risks to disconnected groups make total extinction appear unlikely.[122] These views appear to be widely held among scholars of existential risk.[123]

These arguments should not, however, lead philanthropists to completely dismiss the risk of long-term existential catastrophe emanating from global catastrophic nuclear risks. In a chapter on “Collapse, Recovery, and Existential Risk” in the 2023 volume How Worlds Collapse, Haydn Belfield of the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge provides a critique of the “sanguine view” of collapse risks: “a collapse could destroy humanity’s longterm potential. We cannot yet confidently rule out the prospect of permanent collapse or extinction — and we have good reasons to be concerned that a global civilization that recovered may have much worse prospects.”[124] Broadly, Belfield argues that there is a surprising lack of interaction between collapse scholars and existential risk scholars and outlines three broad critiques of the sanguine view: historiographic biases, a neglect of deep uncertainties about collapse, and a neglect of non-extinction existential risk originating from civilizational collapse.

First, there appears to be a widespread belief that collapse would knock humanity back to an earlier “stage” of history, from which progress could begin anew.[125] In fact, the idea that humanity would simply revert to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and go through “stages” of increasing complexity is simplistic and possibly unrealistic — like the evolution of biological systems, cultural evolution is not directed towards a goal.[126] In the worst case, Belfield writes, this means that modern global civilization may sit atop a fragile perch from which gradual recovery is impossible: “Humanity may have climbed high up a ‘rungless ladder’ — while historic societies fell only a small distance, modern societies may reach ‘terminal velocity’.”[127]

Second, there is simply deep uncertainty about the risk of collapse. For example, there are risks like weapons of mass destruction (e.g. nuclear or biological weapons) falling into the hands of bad actors, for which there are very few historical analogies (only the managed collapse of the Soviet Union — see Case Study on Leverage: Cooperative Threat Reduction later in this report).[128] Most fundamentally, however, a collapse of our society is truly unprecedented.[129] Belfield writes, “a collapse of a global, industrialised society is unprecedented. We cannot be sure that extinction would not follow. The probability of extinction is low, but not imperceptibly low — it is not a rounding error from 0%.”[130]

Finally, extinction is only one of several possible post-collapse worlds that present an existential risk.[131] Large-scale nuclear war may lead to the collapse of global civilization (e.g. through mass starvation caused by nuclear winter), which, in turn, could either lead to civilizational recovery, or to one of three existential catastrophes. The first is human extinction (although some analysts find this unlikely for the reasons discussed above).[132] The second is unrecovered civilizational collapse, in which global society is permanently stuck in a bad state (e.g. because key knowledge and resources such as easily-accessible fossil fuels are lost). The third is civilizational recovery with negative values, such as a totalitarian dystopia.[133]

Belfield argues that there is a wide range of possible recoveries, including the global spread of totalitarian regime types, which would have broad negative consequences for the future of humanity.[134] In this case, civilizational collapse with a wide range of possible outcomes could be especially bad for a number of reasons:

There may be an asymmetry between possible bad outcomes and good outcomes (e.g. if the “floor” on possible dystopias is much lower than the “ceiling” on possible utopias is high, or if there are more possible bad worlds than good worlds).

Our current outcome (general peace and widespread liberalism) may be above average for possible worlds and a “reboot” would therefore lead to a “regression to the mean” with likely worse outcomes.

Good outcomes may be less likely in a recovery than bad outcomes (e.g. because recovery favors militarized totalitarian regimes).

For these reasons and more, Belfield argues that “value is fragile, recovery is risky, and we should not ‘reroll the 100-sided die’.”[135]

Practically speaking, therefore, philanthropists should not be fanatical about prioritizing extinction risks only; we cannot dismiss the possibility that the upper end of global catastrophic nuclear risk could present many kinds of existential risks to human civilization. This uncertainty in turn may lead philanthropists to re-prioritize risks that have a higher likelihood of occurring but a presumed low conditional likelihood of direct extinction (such as nuclear war) over risks that have a lower likelihood of occurring but a presumed high conditional likelihood of direct extinction (such as risks from atomically precise manufacturing or “nanotechnology”). Similarly, Belfield writes, “[If] there is a substantial probability that collapse could destroy humanity’s long-term potential, this should change one’s view of catastrophic risks: climate change, nuclear war and broad biological risks should become more important.”[136] For the purposes of this argument, the uncertainty on the outcomes of civilizational collapse, and the possibility of long-term existential catastrophe, further add to the non-linearity of costs from nuclear war.

What about the Nuclear Taboo?

One possible objection to claims about the non-linearity of war-effects is that any nuclear use, even of just one weapon, would breach the “nuclear taboo” and open the floodgates to further nuclear use (and other WMD use). If this were true, then we ought to model the move from conventional war to small nuclear war to be highly discontinuous in terms of expected cost, leading to a very different risk-reduction strategy. This section outlines reasons for being skeptical of this influential claim.

To summarize the basis for these claims, some scholarship in international security suggests that there are normative restraints — including “taboos” or strong non-use norms — on weapons of mass destruction.[137] These scholars argue that the historical record of presidential decision-making and rhetoric provides evidence for the existence of such a taboo.[138] Thus, if the taboo is broken, there are several concerns. A broken nuclear taboo may result in a renewed arms buildup and more frequent use of large nuclear weapons. As of recently, the United States will retire its megaton-range weapons (B83-1); nuclear weapons states appear to understand that extremely large nuclear warheads — like Tsar Bomba — are an inefficient use of fissionable material.[139] If states’ view of megaton-range weapons were to change (e.g. for reasons of prestige or national glory, if not strategic utility), then ever larger stockpiles and larger deployed arsenals could perhaps pose an elevated risk in a way that current moderate stockpiles do not. Perhaps more concerningly, it could be the case that the breach of the WMD taboo via nuclear weapons use could also make biological weapons development and use more likely, because WMD as a whole are no longer considered off limits — which in turn could lead to civilizational collapse and human extinction.

For the sake of argument, in this section we assume that a nuclear taboo does exist. First, the historical evidence given by scholars of the taboo does suggest that decision-makers sometimes at least act as if they observed such a taboo. Second, we want to engage with the argument on its own terms: assuming that a norm against nuclear use plausibly exists, are there strong reasons to believe that a norm breach would likely lead to widespread use or escalation? It is unclear from the literature on international relations how much norms matter, but evidence from earlier attempts to ban or stigmatize certain weapons classes suggest that once such a norm is breached, norm weakening can follow, but so can norm strengthening.[140]

Sometimes, norm breach appears to engender repeat use. For example, when would-be norm-violators believe that the costs of punishment for a violation are unlikely to outweigh the benefits of use, they may decide that the cost-benefit calculation justifies breaking an apparent norm.[141] For example, in the early twentieth century, nations around the world attempted to negotiate a ban on submarine warfare and aerial bombardment, but the restrictions were quickly breached with the onset of World War II.[142] The restrictions on submarine warfare did not survive the beginning of the war and were immediately broken. The restrictions on aerial bombardment were respected for several months in the early phases of the war, but once violated, resulted in large-scale bombing campaigns of civilian targets, culminating in the use of atomic bombs on Japan.[143] It should be noted that it is not clear from either of these cases whether there ever truly existed a “taboo,” or whether the attempted “bans” were meaningless from the very beginning. That is, it is not clear whether these apparent examples are in the same reference class as the nuclear taboo. Both were legalistic “bans” on weapons that were broken, rather than normatively-constraining and deeply-held moral beliefs about right and wrong (as the nuclear taboo may involve, according to some).

Indeed, some scholars suggest that the breach of a norm against the use of weapons can strengthen that very norm; for example, when norm breach is punished. James Scouras has argued that occasional norm breach may in fact be necessary for a norm to remain in place: “norms, in general, cannot endure indefinitely without periodic violations that provide tangible reminders of their value” — and of the consequences of violation.[144] Similarly, in their discussion of North Korean nuclear first use, Hahn et al. write:

“There is a presumption that once violated, the norm against the use of nuclear weapons cannot endure. But, this presumption is not based on a body of research; it is possible that the response to first use could act to reaffirm the relevance of the norm and that a single violation would not necessarily irreversibly undermine the norm’s existence.”[145]

Is there evidence for these claims? The literature on norm erosion and robustness is thin and data are sparse, but they suggest that we ought to once again be highly uncertain about the sign of the value of norm breach (i.e. whether its effects will be net positive or negative).[146] Strong claims that breaking the nuclear taboo will lead to further WMD norm erosion rather than norm strengthening are simply not supported by historical evidence. Rather, an important additional variable relates to the consequences of norm breach; when other states can impose harsh costs on the violator, they may be able to deter future violations.