Epistemic status: Motivated and biased as a Christian, gazing in awe through rose-tinted glasses at inspiring humans of days gone by. Written primarily for a Christian audience, with hopefully something of use for all.

Benjamin Lay—The Protester

Benjamin Lay, only 4½ feet tall, stood outside the Quaker meeting house in the heart of Pennsylvania winter, his right leg exposed and thrust deep into the snow. One shocked churchgoer after another urged him to protect his life and limb—but he only replied

“Ah, you pretend compassion for me but you do not feel for the poor slaves in your fields, who go all winter half clad.”[1]

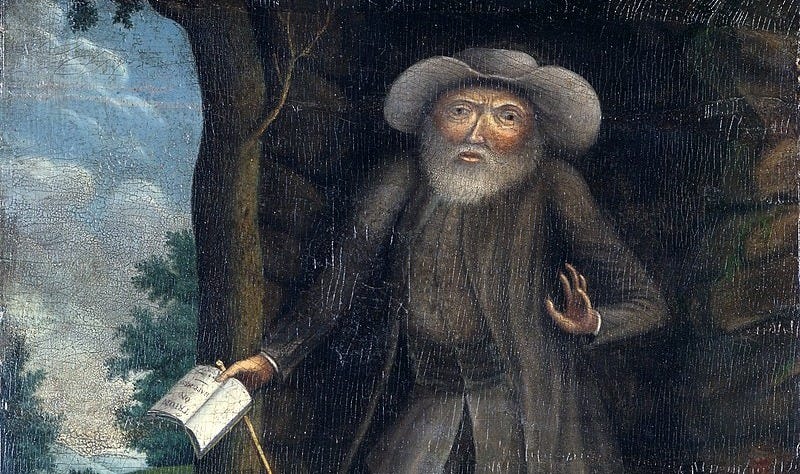

Portrait of Benjamin Lay (1790) by William Williams.

In 1700 Lay’s moral stances were more than radical.[2] He thought women equal to men, was anti-death penalty, pro animal rights and an early campaigner for the abolition of slavery. In the Caribbean he made friends with indentured people while he boycotted all slave produced products such as tea, sugar and coffee. I thought Bruce Friedrich of the Good Food Institute[3] was ahead of his time for going vegan in 1987—well, how about Lay in the 1700s? Many of these moral stances might seem unimpressive now, but back then I would bet under 1% of people held any one of them. These were deeply neglected and important causes, and Lay fought against the odds to make them tractable.

His creative protests were perhaps as impressive as his morals. He smashed fine china teacups in the street saying people cared more about the cups than the slaves that produced tea. He yelled out “there’s another Negro master” when slave owners spoke in Quaker meetings. He even temporarily kidnapped a slave owner’s child, so his parents would experience a taste of the pain parents back in Africa felt while their children were permanently kidnapped. These protests stemmed from a deep spiritual devotion to do and proclaim the right thing – people’s feelings and cultural norms be darned.

Extreme actions like these have potential to backfire, but Lay chose wisely to perform most protests within his own Quaker church. Perhaps he knew that within the Quakers lay fertile ground to change hearts and minds – despite it taking 50 years to make serious inroads. When the Quakers officially denounced slavery In 1758—perhaps the first large organization to do so—a then feeble Lay, aged 77, exclaimed:

“Thanksgiving and praise be rendered unto the Lord God… I can now die in peace.”

John Wesley—The Priest

“Employ whatever God has entrusted you with, in doing good, all possible good, in every possible kind and degree to the household of faith, to all men!” —John Wesley

A key early insight of the “Effective Altruism” movement was the power of “earning to give” – that we can do great good not just through direct deeds, but by earning as much money as possible and then giving it away to effective causes.

Yet one man had the same insight with similar depth of understanding 230 years earlier, outlined in just one sermon derived almost entirely from biblical principles.[4]

John Wesley preached extreme generosity as a clear mandate from Jesus. His message was simple but radical. Earn all you can, live simply to save money, then give the rest to good causes. Sounds great but who actually does that?

He also had deep insight in the pitfalls of earning to give. We should keep ourselves healthy and not overwork. We should sleep well and preserve “the spirit of a healthful mind”. We should eschew evil on the path to the big bucks. And don’t get rich while you’re earning the big bucks, as you risk falling away from your faith and mission. He also understood that earning to give wasn’t a path for everyone.

Where he differs from the current “earning to give” zeitgeist is that living simply was core to his philosophy. He wanted his lifestyle to identify with the poor and always kept a tight lid on expenses, living on just 28 pounds annually for years on end. In one early year he earned 30 pounds, so he gave away just two, while at the height of his ministry he donated 98% of the 1400 pounds he earned that year, the equivalent of $300,000 today—and that not including all the money he raised directly for church and charity. He was also anti-savings and gave everything away as he went, reasoning that Jesus was interested only in building up treasures in heaven. “Leave nothing behind you! Send all you have before you into a better world!”

It fascinates me that a modern atheist philosopher (Singer), and an old conservative preacher came to a similar practical conclusion about giving—one through utilitarian philosophy and the other through deep biblical insight. Wesley was also a vegetarian[5] and anti-slavery advocate after Lay and before Wilberforce. Eight days before he died, he penned an extraordinary letter to a young Wilberforce, just before he introduced the first anti-slavery bill to parliament.

“…Go on, in the name of God and in the power of his might, till even American slavery (the vilest that ever saw the sun) shall vanish away before it.”

William Wilberforce c.1790 (after John Rising) Stephencdickson, Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

William Wilberforce—The Politician

“If to be feelingly alive to the sufferings of my fellow creatures is to be a fanatic, I am one of the most incurable fanatics ever permitted to be at large.” —William Wilberforce

Elected a member of Parliament while only 21 years old and still in University, Wilberforce was described by a London socialite as “the wittiest man in England” and Prime Minister Pitt once remarked that he had “the greatest natural eloquence of all the men I ever knew.” That he was a once in a generation prodigy isn’t in doubt, but early in his parliamentary career he seemed unlikely to change the course of history. During his first four year term he spent much time partying, drinking and gambling, and was often disorganized in his parliament duties.

We don’t know exactly what triggered Wilberforce’s sharp turn to faith at age 25, but we do know the sober repentance wasn’t easy. Years later he confessed to his son “I am sure no human creature could suffer more than I did for some months.” Wilberforce quit drinking, renounced his membership to five gambling clubs and rose early to read his Bible. He considered quitting politics completely[6] but through providence sought advice from John Newton, the ex slave trader turned priest who wrote “Amazing Grace”. Newton convinced Wilberforce to continue, but to now use his influence to do good.

It’s easy to look back and see abolishing slavery as a no-brainer, but that wasn’t the case. The British public wasn’t particularly concerned about the issue, although the Quakers (Lay) and Methodists (Wesley) actively campaigned against the trade. In 1789, four years after his conversion, Wilberforce was the first to strongly speak out against slavery in Parliament but his anti-slavery bill failed 166 votes to 88. It took another 15 years for Parliament to legislate against the slave trade, and 43 years of hard work before in 1834 Britain finally abolished slavery completely and slaves were freed.

As terrible as it is to consider these numbers, between 1.2 and 2.4 million people out of the 12 to 15 million transported during the trade’s torrid history may have died on boat journeys. Counterfactual histories are tough, but if the work of Wilberforce and others brought abolition forward by 20 to 50 years, they may have saved hundreds of thousands of lives and prevented much suffering. Of course the credit is shared between many, including those like Lay who helped open the Overton window for abolition, and former slave Olaudah Equiano whose book opened the eyes of the British public.

Although abolition was his defining achievement, Wilberforce had a voracious ambition to reduce suffering and build the global church. He advocated for prison reform, founded perhaps the most influential international mission society of the day and to round off his EA credentials, in 1822 he even helped launch the first ever animal rights charity, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA).

“To live our lives and miss that great purpose we were designed to accomplish is truly a sin. It is inconceivable that we could be bored in a world with so much wrong to tackle, so much ignorance to reach and so much misery we could alleviate” —Wilberforce

What they had in common

Devotion to biblical truth over cultural norms. They had an ability to ignore cultural norms and see the biblical truths that pierced through. Truths that in the right hands could transform society into something better.

Use of what power or privilege they had not to gain more power or wealth, but to further their causes.

Inspiring friends. Wesley had evangelist Whitfield. Lay had his incredible wife Sarah and… Benjamin Franklin. Wilberforce had the “Clapham sect” where influential Christian reformers planned their next steps.

They did one thing for a long time until they were good at it and they broke through. Wesley reportedly delivered 3 sermons daily for 50 years, Lay never stopped provoking his Quaker kin, while Wilberforce rallied Parliament again and again until slavery was finally abolished.

Whole hearted love and devotion to God. I was struck by how often their writing gushed in a way we might today find cringe, or “over-the-top”.

“God’s grace is sufficient for us in time of need, as our eyes are single towards him and him alone for advice, counsel, and strength at all times. Glory endless is with him” —Lay

What we can perhaps learn from them

With great humility I gingerly offer these lessons I’ve gleaned from looking at the lives of these great humans. Many of these ideas might be difficult or even impossible at our current stage of life and I certainly don’t follow them all.

Surround yourself with inspiring people: This can be a tough task, but it helps if we have better people than us among our life partners, friends and mentors.

Start with the words of Jesus, not cultural norms: Stepping out of cultural norms can feel almost impossible, but the words of Jesus can free us from expectations and standard career paths into better ways of being and doing.

The importance of Spiritual Disciplines: We might not manage Wesley’s fasting twice a week or Wilberforce’s daily Bible reading, but maybe we can at least turn to God before our smartphone every morning? Even this simple task can be harder than it seems and I still fail most days.

There’s no set formula for doing good: These three men worked in wildly different ways. Lay through wild protest, Wesley through influencing individuals with preaching, Wilberforce through policy change. What advantages do we have in our current stage of life and work, however small, that we can leverage to do more good?

Don’t be discouraged—bearing fruit can take decades: Lay and Wilberforce only saw the progress they dreamed of on their deathbeds, and for Lay especially his victory was hardly overwhelming—barely even the first step to abolition. Who knows what impact whatever we do now might have years down the line?

Special appreciation to the EA for Christians folks, Dominic Roser for his examination of Wesley and “Benjamin Lay Day” on the forum for the inspiration and background work. Also to the amazing Susanna Wesley, mother of John

[7]

- ^

- ^

For a more in-depth look at Lay’s life and exploits check out… https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/dM93vHvLTgpk8pLSX/celebrating-benjamin-lay-died-on-this-day-265-years-ago

- ^

An amazing guy with a compelling story which you can hear on the Christian’s for Impact Podcast

- ^

- ^

Mainly it seems for frugality reasons

- ^

It wasn’t cool or easy to be a serious Christian in parliament at the time

- ^

I only discovered her story after writing this—not so much is known aboutr her as sadly was the case for so many women at the time. An impressive biblical scholar, her next-level teaching and mentoring of her 11 kids gave them a huge boost toward their later success.

Thanks for writing this Nick, I found it really inspiring.

I’m not a Christian, but can definitely admire the authenticity, sincerity and dedication of people who take faith seriously, and repeatedly inquire about what it asks of them. Forever needing more of those values in my own life, and it’s motivational to read about people who succeeded in holding them.

PS- the Benjamin Lay day link at the end links to this post (the one we are on right now), not to the event.

What about Temistocles (for the Greek victory against the Persians), the Stadtholder King William III (for defeating the reactionary absolutism of Luis XIV and James II), Washington and Madison (for creating the United States), or Churchill for stopping Hitler?

Who shall we praise, those in the past that had the purest intentions, or those who brougth more progress? Some of the people I have selected have biographies full of cruel ambition and large scale crime. All of them were the architects of moral and material progress (mostly defeding the statu quo against reactionary forces).

Too much praise for Altruism, because it gets universal sympathy. But what about Effectiveness?

We praise people to hold them up as examples to emulate (even though all people are imperfect and thus all emulation should be partial). Holding people who committed large-scale crime up for emulation has a lot of downsides. Moreover, the effectiveness of effective historical figures is often context-dependent, and difficult to apply to greatly different circumstances. Finally, I’m not convinced that praise of effective leaders like Washington, Madison, and Churchill is neglected in at least American public education and discourse (but this may have changed since my childhood).

I agree with the rest of your comment, but I don’t like “neglectedness” being applied in this context. MLK jr, for example, is certainly not “neglected” of praise, but I think his writings and methods still have a lot to teach us.

I’d say a better argument against washington is that he was a slaveowner and did not stop the spread of slavery when he had the power to do so. I’m not sure “turn a blind eye to the great evils of your day” is a great lesson to be learned.

Fair—I took Arturo’s take to be that there was an undersupply of praise of people high in effectiveness relative to praise of people high in altruism, such that we should do more of the former. To me, the amount of “airtime” Washington et al. get is evidence against that take.

Lincoln was always a very ruthless political operative, but we praise him because in the 1860s the direction of History was mostly “end slavery”.

In the 1770s, the frontier was “no taxation without representation”, and turning a blind eye to slavery was almost inevitable, specially if your political base was from Virginia.

Progress is about concentrating the social force in the place where it can lead to change.

That implies turning a blind eye to anything else.

I’d probably give somewhat more credence to this if Washington didn’t own 124 slaves at the time of his death. People in Virginia were emanicipating their slaves; Washington could have but did not during his lifetime. That suggests his actions were not merely constrained by what was possible for a politician to accomplish at the time.

Lincoln was pretty willing to enshrine slavery into the Constitution forever to save the Union (https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corwin_Amendment), so I find his anti-slavery reputation to be too strong.

And to imagine Benjamin Lay was raging against slavery in Pennsylvania 150 years before the Corwin Amendment… I agree Lincoln’s reputation is too strong, although he did actually achieve what was needed for abolition.

Oh, sure. Both Washington and Lincoln were more interested in the United States than in slavery. This show that their priority was political instead of ethical. And they were magnificently right, because the United States is to some extent “a machinery of freedom”, an institutional system with the right bias, and that is more important than some material injustice here and now.

More over, I am not defending the ethical superiority of my chosen “saints”; I simply suggest that purity of intention is not the most important valuation criterium. I am simply taking a consequentialist reading of History.

More important than the point of Washington personally owning slaves, the US was two generations behind the UK in banning slavery. A counterfactual where the US didn’t leave Britain (or seceded peacefully later on in a manner similar to Canada, Australia, etc) likely means emancipation of slaves much earlier. So at least contemporaneously the “machinery of freedom” argument is implausible; you’d basically need the World Wars/maybe the Cold War before the argument becomes plausible.

Would UK have banned slavery if the US where still a British colony? Moreover, with a large un represented colonial empire of people of English descent, would the UK keep its parliamentarian path? Many British Whig took a pro colonial position for some reason…

The US was clearly not a “machinery of freedom” before 1865, given that slavery was legal. So if it ever became a machinery of freedom (I struggle to think of when that would be), it was a hundred years after washingtons presidency, and I hesitate to give him credit for it.

I strongly disagree that Lincoln was correct to prioritize the union over ending slavery (though remember that this was when he was facing a risk of a massive war, a war which when it did break out killed hundreds of thousands). For one thing he probably wasn’t doing that to preserve “freedom” in some universalist sense after cost benefit analysis, but rather because he valued US nationalism over Black lives. But I still think this is a little simplistic. In the late 18th century, many, probably most countries and cultures in the world either had slavery internally, or used slavery as part of a colonial Empire. For example, slavery was widepsread in Africa internally, many European countries had empires that used slave labour, Arabs had a large slave trade in East Africa, the Mughals sold slaves from India, and if you pick up the great 18th century Chinese novel The Story of the Stone, you’ll find many characters are slaves. Meanwhile, the founding ideals of the US were unusually liberal and egalitarian relative to the vast majority of places at the time, and this probably did effect the internal experience of the average US citizen. The US reached a relatively expanded franchise with many working class male citizens able to vote far before almost anywhere else. So the US was not exceptional in its support for slavery or colonialist expansion (against Native Americans), but it was exceptional in its levels of internal (relative) liberal democracy. I think its plausible that on net the existence of the US therefore advanced the cause of “freedom” in some sense. Moving forward, it seems plausible that overall having the world’s largest and most powerful country be a liberal democracy has plausibly advanced the cause of liberal democracy overall, and the US is primarily responsible for the fact that German and Japan, two other major powers, are liberal democracies. Against that, you can point to the fact that the US has certainly supported dictatorship when it’s suited it, or when it’s been in the private interests of US businesses (particularly egregiously in Guatemala was genuinely genocidal results*). But there are also plenty places where the US really has supported democracy (i.e. in the former socialist states of Eastern Europe), so I don’t think this overcomes the prior that having the world’s most powerful and one of its richest nations, with the dominant popular culture, be a liberal democracy was good for freedom overall. Washington and the other revolutionaries plausibly bear a fair amount of responsibility for this. And in particular, Washington’s decision to leave power willingly, when he probably could have carried on being re-elected as a war hero until he died probably did a lot to consolidate democracy (such as it was) at the time. Of course, those founders who DID oppose slavery are much more unambiguously admirable.

*More people should know about this, it was genuinely hideously evil: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guatemalan_genocide

I’m mainly taking issue with the “machinery of freedom” claim and the idea that the US is uniquely free. I would say the US is more free than average, but it’s hardly exceptional.

The US gave women the right to vote in 1919, whereas Australia had it since 1902, the UK had it in 1918, etc. And of course, there wasn’t universal right to vote until the civil rights movement.

Looking further back, while slavery was widespread, many other countries were much better than the US on this issue: the uk (no saint) banned it in 1807, over half a century before the US went to war with itself over the issue.

I’m happy to credit washington with support of democracy, but this idolisation just seems a little weird to me.

Compared to what? How many countries had a more extensive political participation? Of course, slavery was an abyssal horror, but it was almost universally accepted until 1807.

Until that date America was the most democratic country in the world, and regarding slavery was not worse than others (in fact, half of America always resisted slavery, finally at an enormous cost).

As Tocqueville understood, democracy is auto catalytic. When you begin with a 3% franchise in 1688, the slope towards 100% is in place. By importing the Glorious Revolution, the American Revolution both put the process in motion in a continental size nation and perhaps avoided involution in UK

So from 1787 to 1807?

Except that the french revolution happened during this same period, and Robespierre abolished slavery in french colonies in 1792. Of course, napoleon reestablished it in 1802, so we can say that america was the most democratic country from 1787-1792 and then from 1802-1807. Hardly a great case for the machinery of freedom.

Is there any more representative country in the world between 1789 and let’s put the Civil War in 1864? Well, for sure Switzerland, but what else? Tocqueville opinion was that the US was not only formally, but also materially the most democratic among the world powers. I do not see many reason to doubt his observations.

William III began his career very probably by killing the de Witt brothers, and was always a very dry and extremely arrogant character. In Ireland probably he is still hated (by the Catholics).

But probably he and Newton are the most important persons of the Modern Era.

This is the dark side of Christianity (either religious or secular): salvation is only about ethics, so the rest or accomplishment is at most secondary, often suspicious.