You probably won’t solve malaria or x-risk, and that’s ok

Contrary to my carefully crafted brand as a weak nerd, I go to a local CrossFit gym a few times a week. Every year, the gym raises funds for a scholarship for teens from lower-income families to attend their summer camp program. I don’t know how many Crossfit-interested low-income teens there are in my small town, but I’ll guess there are perhaps 2 of them who would benefit from the scholarship. After all, CrossFit is pretty niche, and the town is small.

Helping youngsters get swole in the Pacific Northwest is not exactly as cost-effective as preventing malaria in Malawi. But I notice I feel drawn to supporting the scholarship anyway. Every time it pops in my head I think, “My money could fully solve this problem”. The camp only costs a few hundred dollars per kid and if there are just 2 kids who need support, I could give $500 and there would no longer be teenagers in my town who want to go to a CrossFit summer camp but can’t. Thanks to me, the hero, this problem would be entirely solved. 100%.

That is not how most nonprofit work feels to me.

You are only ever making small dents in important problems

I want to work on big problems. Global poverty. Malaria. Everyone not suddenly dying. But if I’m honest, what I really want is to solve those problems. Me, personally, solve them. This is a continued source of frustration and sadness because I absolutely cannot solve those problems.

Consider what else my $500 CrossFit scholarship might do:

I want to save lives, and USAID suddenly stops giving $7 billion a year to PEPFAR. So I give $500 to the Rapid Response Fund. My donation solves 0.000001% of the problem and I feel like I have failed.

I want to solve climate change, and getting to net zero will require stopping or removing emissions of 1,500 billion tons of carbon dioxide. I give $500 to a policy nonprofit that reduces emissions, in expectation, by 50 tons. My donation solves 0.000000003% of the problem and I feel like I have failed.

I want to reduce existential risk, and think there is a 10% chance that AI will kill everyone. I donate $500 to MIRI, which reduces the chances of extinction by 0.01 microdooms[1]. My donation solves 0.000000001% of the problem and I feel like I have failed.

I can’t come close to solving even 1% of these problems on my own. Not even 0.0001%.

The man who failed to fully solve a genocide

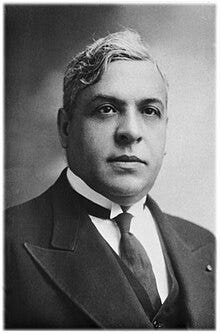

Aristides de Sousa Mendes was a Portuguese aristocrat in the early/mid 20th century who had some interesting postings around the world as a diplomat. He even had the Sultan of Zanzibar as godfather to one of his kids. In 1938 he ended up taking a comfortable position as Consul at the Portuguese consulate in Bordeaux, France. I often find myself thinking about his work and haven’t heard him discussed in EA circles, so here is some of his story.

On May 10th 1940, Nazi Germany launched its invasion of France, generating mass movement of refugees, especially Jews. Portugal was officially a neutral country and hundreds in Bordeaux flocked to the Portuguese consulate in the hope of getting a visa to escape to safety. Unbeknownst to them, Portugal’s dictator, Salazar, had issued a secret order 7 months earlier forbidding the issuance of visas to most refugees, in particular “stateless persons”, which at the time primarily meant Jews.

de Sousa Mendes complied with the order, telling applicants that no visas would be issued, but he did try applying for visas on behalf of a rabbi and his family. Lisbon rejected them. de Sousa Mendes then spent 3 days locked in his bedroom, apparently torn between his conscience, and his professional and patriotic duty.

After those 3 days he emerged with a new mission— he would issue those visas to the rabbi’s family anyway, and he would issue visas to anyone who asked for them. He quickly got to work. He set up a bureaucratic assembly line, including his own children, to process visas as efficiently as possible, working night and day.

Word eventually reached the government in Lisbon, who ordered him to cease and eventually sent officials to stop him from issuing the visas. In the 7 days before his visa operation was shut down, at least 1,500 visas had been issued, likely thousands more. While travelling back to Lisbon for a disciplinary hearing, de Sousa Mendes managed to pass through the consulate in Bayonne and, hiding the fact that he was under disciplinary action, successfully ordered officials to issue hundreds more refugee visas.

Upon arrival in Lisbon he was dismissed from his post and denied his pension. Although the visas had been issued explicitly against government orders, they were nonetheless honoured, with many recipients using Portugal as a launch pad to move to the USA. The exact number of visas issued by de Sousa Mendes is not clear. Most estimates are in the range of 3,000 to 10,000 visas, with some visas covering more than one person[2]. He died in 1954, impoverished, with his story only gaining recognition decades later. In 1988 the Portuguese parliament officially pardoned him and posthumously promoted him to the rank of ambassador. A public poll in 2007 named him the 3rd greatest Portuguese person in history.

But de Sousa Mendes’ work was tiny against the enormity of the genocide. Even if he issued visas to as many as 10,000 people and all 10,000 would otherwise have been murdered, his contribution was to alleviate just 0.1% of the horror of the Holocaust.

Saving starfish

There is a corny parable I’ve heard a few times in nonprofit circles. A man is walking along a beach after a violent storm. The storm has caused many thousands of starfish to be washed up onto the beach, doomed to dry out in the heat of the sun. He sees a young boy picking up individual starfish and throwing them into the sea. He asks him, “Why are you bothering? You will never be able to save all of the starfish, your efforts don’t matter”. The boy replies, “But it matters to this one”, and throws another starfish into the cool water.

I used to see this parable as an argument for old-school, inefficient nonprofits. The kind that say “What matters is that we are doing something”, rather than taking the time to reflect on whether what they are doing is effective, or the most effective thing they could do with their resources. I’m now less negative. If you are reasonably confident that what you are doing is the most effective thing you can do, then it doesn’t matter if it fully solves any problem. You do it because it matters to the people you are able to help. The boy is right: if it matters to this one, then it matters.

Big problems are actually solved piece by piece

I have recently been thinking about de Sousa Mendes and the starfish boy a lot. Some problems, many problems, are so big that anything I do about them will not bring them any more than a tiny fraction closer to being solved. Sometimes, that feeling can make me want to give up. Or at least, give up on those big problems and find ones I can solve by myself, like the CrossFit scholarship.

But de Sousa Mendes and the starfish boy remind me that large problems are often comprised of many small ones stacked up. They remind me that if my donation can only save the life of one child from malaria, when hundreds of thousands will die this year, the donation still matters because that one child matters. And while my donation to the CrossFit scholarship would fully fix a problem, and my malaria donation only fractionally dents malaria, if the donation saves a life then it has actually “solved” malaria for that child.

Sometimes, we will be a part of a humanity-scale endeavour that really does solve a big problem, like smallpox eradication. Other times, we will play our part in chipping away at a problem that we hope others will eventually solve, like climate change. And at times, we might face a problem like de Sousa Mendes, where we are simply making our tiny dent in a problem that will not be solved, not in time, and where the horrors will still continue. In each case, what matters isn’t whether we solve the big problem. All that can matter that is we do the best we can, and solve the small pieces that we can, because in every small piece of the problem is not a rounding error but a living being, and your work matters– to them.

I loved your telling of de Sousa Mendes’ story — thanks for sharing it. The moral courage he showed is really beautiful to me :)

The basic premise of this post: It’s better to solve 0.00001% of a $7 billion problem than to solve 100% of a $500 problem. (One could quibble with various oversimplifications that this formulation makes for the sake of pithiness, but the basic point is uncontroversial within EA.)

The key question: If this point is both true and obvious, why do so many people outside EA not buy it, and why do so many people within EA harbor inner doubts or feelings of failure when acting in accordance with it?

We should ask ourselves this not only to better inspire and motivate each other, or to better persuade outsiders, but also because it’s possible that this phenomenon is a hint that we’ve missed some important consideration.

I think the point about Aristides de Sousa Mendes is a bit of a red herring.

It seems like more-or-less a historical accident that Sousa Mendes is more obscure than, e.g., Oskar Schindler. Even so, he’s fairly well-known, and has pretty definitively gone down in history as a great hero. I don’t think “but he only solved 0.1% of a six-million-life problem” is an objection that anyone actually has. Saving 10,000 lives impresses people, and it doesn’t seem to impress them less just because another six million people were still going on dying in the background.

(The main counterargument that I can think of is the findings of the heuristics-and-biases literature on scope neglect, e.g., Daniel Kahneman’s experiment asking people to donate to save oil-soaked birds. I think that this kind of situation is a little different; here, you’re not appealing to something that people already care about, you’re producing a new problem out of thin air and asking people to quickly figure out how to fit it into their existing priorities. I think it makes sense that this setup doesn’t elicit careful thought about prioritization, since that’s hard, and instead people fall back on scope-insensitive heuristics. But this is a very rough argument and possibly there’s more literature here that I should be reading.)

When people are skeptical, either vocally or internally in the backs of their minds, of the efficacy of donating $500 to the Rapid Response Fund, I don’t think it’s because they think the effects will be analogous to what Sousa Mendes did, but that that’s not good enough. I think it’s because they suspect that the effects won’t be analogous to what Sousa Mendes did.

In a post about a different topic (behavioral economics), Scott Alexander writes:

I think people are worried about something like this, and I think it’s not unreasonable for them to worry.

I once observed an argument on a work mailing list with someone who was skeptical of EA. The core of this person’s disagreement with us is that they think we’ve underestimated the insidiousness of the winner’s curse. From this perspective, GiveWell’s top charity selection process doesn’t identify the best interventions—it identifies the interventions whose proponents are most willing to engage in p-hacking. Therefore, you should instead support local charities that you have personally volunteered for and whose beneficiaries you have personally met—not because of some moral-philosophical idea of greater obligations to people near you, but because this is the only kind of charity that you can know is doing any good at all.

GiveWell in particular is careful enough that I don’t worry too much that they’ve fallen into this trap. But ACE, in its earlier years, infamously recommended interventions whose efficacy turned out to have been massively overestimated. I suspect that this is also true of some interventions that are still getting significant attention and resources from within EA, even if I can’t confidently say which ones.

And then of course there’s just that big problems are complicated and the argument for why any particular intervention is effective typically has a lot of steps and/or requires you to trust various institutions whose inner workings you don’t understand that well. All this adds up to a sense that small donations to solve a big problem wind up just throwing money into a black hole, with no one really helped.

This, I think, is the real challenge that EA needs to overcome: not the small size of our best efforts relative to the scope of the problem, but skepticism, implicit or explicit, loud or quiet, justified or unjustified, that our best efforts produce real results at all.

FWIW I think that GiveWell selects organisations are based on close to the best evidence base we have, kind of the opposite of “p-hacking”. It doesn’t make sense to me that anyone can be sure their local charity is doing “any good at all” without knowing the counterfactual.

My classic example to illustrate this is the original microloans in Bangladesh. Everyone could “see” how much they were helping as most of the women loaned money were growing successful businesses. Until they looked at cohorts of women who didn’t get loans and maybe of them were also running successful businesses as well. The loans were helping counterfactual but only in a minor way—most of the women would have done great anyway without the loan.

I think with situations like ACE charities that ended up not being useful it’s less of a p-hacking problem and more of an uncertainty problem. They just don’t have the same rigo to of us evidence base for efficacy as global health interventions so there are likely to be more failures and that’s hard to avoid.

Extreme nitpick, but you mean the optimizer’s curse, not the winner’s curse. The winner’s curse is that when you win an auction, you should expect to have overpaid (similar dynamics to the optimizer’s curse though.) The optimizer’s curse is really interesting and worth a read IMO! Doesn’t come from worries with p-hacking but applies even when the data you look at is fair and unbiased. IIRC due to the distribution of random errors but I could be wrong.

I think something that may help donors feel like they’re actually doing something and could be cool is a GiveWell-ran but kickstarter aesthetic website for charities. Charities set their moonshots, breaks it down to manageable bitesize pieces and establishes goals based on them. Different promises are made to donors for different goals of donation reached. Donors also have different tiers based on how much they donate.

E.g. We want to distribute malaria vaccines to everyone in Nigeria. For $x donated, we’ll distribute vaccines to all children under 5 in the state of Ondo in Nigeria, and send stickers out to all donors. If we reach $x + y, we will expand to the neighboring state of Eikiti as well and all silver+ tier donors will get a handwritten card. Donating $(x * 0.001) grants you bronze tier, $(x * 0.005) grants you silver, etc.

With the right UI design, I think donors could feel much more like they’re really contributing because of the relative tiers, and their ability to see the project get closer to pre-established goals specifically due to their donation. There’s also a much cleaner feedback cycle when donating $z → you get letters/videos/whatever else emotionally appeals to donors. And I imagine you could also add a lot of community incentives and gamification elements to something like this.

Your story reminded me of a study in which students were more supportive of a safety measure that would save 85% of 150 lives than one that would save 150 lives. People commonly think in relative terms and may not be sure if 1 life or 150 lives is a lot. But 85% sounds like a lot. And 0.0001% surely doesn’t. As you correctly point out, though, these proportions don’t matter to the lives of the people being helped or saved.

Upvoted and I endorse everything in the article barring the following:

> If you are reasonably confident that what you are doing is the most effective thing you can do, then it doesn’t matter if it fully solves any problem

I think most people in playpump-like non-profits and most individuals who are doing something feel reasonably confident that their actions are as effective as they could be. Prioritization is not taken seriously, likely because most haven’t entertained the idea that differences in impact might be huge between the median and the most impactful interventions. On a personal level, I think it is more likely than not that people often underestimate their potential, are too risk-averse, and do not sufficiently explore all the actions they could be taking and all the ways their beliefs may be wrong.

IMO, even if you are “reasonably confident that what you are doing is the most effective thing you can do,” it is still worth exploring and entertaining alternative actions that you could take.

Totally agreed! I very much assumed my audience was very EA and already stepping back on cause-prio + intervention choice every so often. You are right that that often isn’t the case, and the way I’ve framed things here might encourage some folks to just plough on and not ask important questions on whether they are working on the right thing, in the right way.

Thanks for sharing these perspectives Rory! On an emotional level, combining what you are saying with the thought of there being others that are also trying their best to e.g. save starfish, makes me think “Maybe, just maybe, we can solve the whole problem”—and that gives me both inspiration and hope :)

this is great. thank you

Whilst this works for saving individual lives (de Sousa Mendes, starfish), it unfortunately doesn’t work for AI x-risk. Whether or not AI kills everyone is pretty binary. And we probably haven’t got long left. Some donations (e.g. those to orgs pushing for a global moratorium on further AGI development) might incrementally reduce x-risk[1], but I think most won’t (AI Safety research without a moratorium first[2]). And failing at preventing extinction is not “ok”! We need to be putting much more effort into it.

And at least kick the can down the road a few years, if successful.

I guess you are much more optimistic about AI Safety research paying off, if your p(doom) is “only” 10%. But I think the default outcome is doom (p(doom|AGI)~90% and we are nowhere near solving alignment/control of ASI (the deep learning paradigm is statistical, and all the doom flows through the cracks of imperfect alignment).

Thank you for this! With respect to the starfish story, the boundary around which you draw problems seems important. You can say “there’s this One Big Problem wherein this big group of starfish will dry out on the beach,” and this framing invites completionism. And to be clear, save all the starfish you can! But you can also say “there are several individual problems wherein individual starfish will individually dry out on the beach,” and this framing invites viewing each starfish saved as a win. With some problems, labeling it all as One Big Thing can help emphasize systematic failures and points of leverage to solve more of the individual component problems. But it’s important to remember that, at least in some contexts, solving the whole thing is only instrumental to solving the component problems.

Executive summary: While most individuals cannot singlehandedly solve major global issues like malaria, climate change, or existential risk, their contributions still matter because they directly impact real people, much like how historical figures like Aristides de Sousa Mendes saved lives despite not stopping the Holocaust.

Key points:

People are often drawn to problems they can fully solve, even if they are smaller in scale, because it provides a sense of closure and achievement.

Addressing large-scale problems like global poverty or existential risk can feel frustrating since individual contributions typically make only a minuscule difference.

Aristides de Sousa Mendes, despite violating orders to issue thousands of visas during the Holocaust, only alleviated a small fraction of the suffering, yet his actions were still profoundly meaningful.

The “starfish parable” illustrates that helping even one person still matters, even if the broader problem remains unsolved.

Large problems are ultimately solved in small, incremental steps, and every meaningful contribution plays a role in the collective effort.

The value of altruistic work lies not in fully solving a problem but in making a tangible difference to those who are helped.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.