Why EAs researching mainstream topics can be useful

This post does not necessarily represent the views of my employers.

We could call a topic more “mainstream” the less neglected it is; the more it overlaps with topics and fields that are established and of interest to many people outside the EA community or associated communities[1]; and the more you’d expect that people outside those communities would care about the topic. For example, reducing armed conflict and improving politics are more mainstream topics than are the simulation argument or large-scale risks from AI. (For elaboration on these points, see the Appendix.)

It’s reasonable to ask: Why and how can it be useful for people in the EA community to research relatively mainstream topics? This seems especially worth asking in cases where those people lack relevant expertise and their research projects would be relatively brief.[2] But it may also be worth asking in cases where the person has relevant expertise, would work on the project for longer, or is considering whether to become an expert on a relatively mainstream topic.

Summary

I think there are four main, broad, potential paths to impact from such work:[3]

The research could improve behaviours and decisions made within the EA community. But how?

The research could tackle important questions that differ from those tackled in existing work on a topic, even if the topic overall is mainstream.

The research could provide better answers than the existing work has on the same questions that the existing work aims to answer.

The research could bring existing knowledge, theories, ways of working, etc. from other communities into the EA community.

The research could improve behaviours and decisions made within other communities (e.g., slightly improving the allocation of large peacebuilding and security budgets). As above, this could result from the research:

tackling important questions that differ from those tackled in existing work on a topic

providing better answers than the existing work has

simply bringing existing knowledge, theories, ways of working, etc. from the EA community into other communities

Doing this research could allow the researchers to build networks between the EA community and other communities, which could help with things like recommending non-EA organisations, projects, job-seekers, experts, etc. for EAs[4] to fund, work for, hire, get advice from, etc., and vice versa

Doing this research could equip the researchers with the knowledge, skills, connections, and credibility they need to later get and effectively use influential roles in other communities

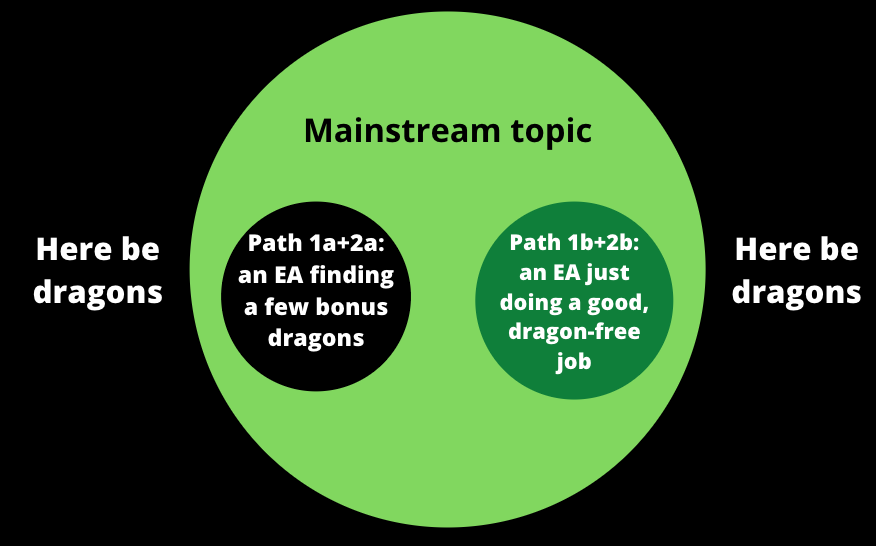

Here are rough, diagrammatic representations of these paths:

Ultimately, I think that:

A topic being more mainstream does typically somewhat reduce how valuable it’d be for a longtermist to research it

But this effect doesn’t always hold

And even when this effect holds, it may be relatively weak, can be outweighed by other factors, and can be weakened further by explicitly thinking about the paths to impact discussed above when planning, conducting, and disseminating one’s research

Purpose and caveats for this post

This post simply attempts to crystallise and share my thoughts on the question “Why and how can it be useful for people in the EA community to research relatively mainstream topics?”[5] I hope the post will help you:

Understand part of my personal reasoning behind and theories of change for some of the research that I plan to do;

Understand part of what might be the reasoning behind and theories of change for some research that other EAs are doing;

Think about what research you should do or support (where “supporting” could be via funding, mentorship, etc.); and/or

Think about how the research you do or support should be done[6]

(See also Do research organisations make theory of change diagrams? Should they?)

To be clear, I do not necessarily intend to advocate for an increase in the overall fraction of EA research that’s focused on relatively mainstream topics. I think it’s clearly the case that some EA researchers should tackle relatively mainstream topics, that others should not, that some should do both, and that this depends mostly on the specifics of a given situation. This post provides many points and counterpoints, notes that some things are “often” the case without saying how often, etc.; in order to make specific decisions, you’d need to combine these general considerations with your knowledge of the specific situation you face.

All examples in the following sections are purely for illustration. Also, the examples focus on longtermism rather than EA more broadly, but that’s simply because I know and think more about the question this post addresses in relation to longtermism than in relation to other cause areas; I do think the same basic claims would apply for other cause areas too.[7]

1. Improve behaviours and decisions within the EA community

1a. Research non-mainstream questions within mainstream topics

For example, there are large bodies of work on war, policymaking, and authoritarianism, but very little work explicitly focused on how those things are relevant to the long-term future, or what implications that has for our actions. How much would “war” increase or decrease existential risk or the chance of other trajectory changes? By what pathways? How does this differ based on the type of war and other factors? These questions are crucial when deciding (a) how much to prioritise work on “war” and (b) what specific work on war to prioritise (or to actively avoid due to downside risks).

There are also various other types of high-priority, non-mainstream questions that can often be found within mainstream topics. For example, questions about the importance, tractability, and neglectedness of a problem area; the cost-effectiveness of various possible actions; or probabilistic forecasts of what the future will bring or what impacts an action would have.

Of course, a lot of existing work is relevant to such questions, even if it’s not motivated by them. And in some cases, people will already have sufficient clarity on those questions for the decisions they need to make. This clarity could come from things like making relatively obvious inferences from the work that does exist, or having conversations with people who’ve thought about these issues but who haven’t written their thinking up.

But there are also many cases where more work on those questions should be a high priority. And such cases should be expected to occur more often as the EA community grows, because as the community grows:

There’s a larger community to benefit from the externalities that come from exploring different problems and interventions that might turn out to be worth prioritising, learning what implications those problems and interventions have for other issues, etc. (see Todd, 2018)

EAs are more likely to work on a topic if it’s more neglected (holding other factors constant), which should cause the gaps in neglectedness to decrease over time, increasing how often someone should work on something despite it being less neglected.[8]

But even if there are high-priority non-mainstream questions within mainstream topics, why should we expect an EA without relevant expertise to be able to generate useful answers within a relatively brief time? Firstly, the neglectedness of the specific question may mean it’s relatively easy to improve our answers to it.

Secondly, the EA need not start from scratch; they may be able to simply synthesise and draw implications from the mainstream work that’s relevant to—but not focused on—the question of interest. For example, the EA could have conversations with experts on the mainstream topic and directly ask them the non-mainstream questions, then publish notes from the conversation or a write-up that uses it as an input.

Examples of work with this path to impact include 80,000 Hours’ problem profiles and career reviews, many cause area reports by Open Philanthropy and Founders Pledge, and many conversation notes published by GiveWell or Open Philanthropy.

1b. Provide better answers than the existing work has

In many (but not all) cases, EAs could provide better answers than the existing work has on the same questions that the existing work aims to answer. And this can happen even for mainstream topics, for EAs with relatively little relevant expertise, and for relatively brief research projects, although each of those features makes this achievement less likely.

I expect some readers will feel those statements are so obviously true as to not be worth saying, while others will feel the statements smack of arrogance, insularity, and epistemic immodesty. Interested readers can see further discussion in a comment.

1c. Bring existing knowledge, theories, etc. into the EA community

Here’s a procedure that could in theory be followed, but that’s in practice far too difficult and time-consuming:

Each EA could notice whenever something they’re doing or deciding on would benefit from drawing on one of the myriad sprawling bodies of knowledge (or theories, techniques, ways of working, etc.) generated outside the EA community

They could then work out which body of knowledge would be relevant to what they’re doing or deciding on

They could then sift through that body of knowledge to find the most relevant and reliable parts

They could then get up to speed on those parts, without learning misconceptions or forming bad inferences in the process

There are many possible ways to deal with the fact that the above procedure is too difficult and time-consuming to follow in practice. One way starts with some EAs going through the above procedure for some subset of the types of actions or decisions EAs need to make, or for some subset of the bodies of knowledge that are out there. (For example, they could learn what’s already known about great power war, or what longtermism-relevant things are already known in political science.) These EAs can then do things like:[9]

Publishing write-ups about what they’ve learned (e.g., book notes, literature reviews, other summaries)

Contacting specific actors (e.g., funders) to explain specific takeaways relevant to those actors’ decisions

Being available to give input where relevant (e.g., to give second-opinions on grant decisions, career decisions, or research project ideas)

Why would this be better than the ultimately-influenced-people simply going through the above procedure themselves, finding write-ups by non-EA, or being contacted by or contacting non-EAs? In many cases, it won’t be. But here are some (inter-related) reasons why it often can be useful:

Busy deciders, delegation, and specialisation

As an analogy: Although a CEO retains final decision-making authority, they typically find it useful to delegate most option-generation, analysis, and decision-making to subordinates or contractors. And it’s typically useful for those subordinates or contractors to specialise for particular types of decisions or areas of expertise.

Likewise, it can be useful for e.g. grantmakers to be able to draw on the public work or tailored input of other people who’ve specialised more than the grantmaker for something relevant to a given decision.

Actor-level trust and relationships

Decision-makers can spend less time vetting some work or input, and place more weight on it, the more they trust the actor—whether an individual or an organisation/group—who provided that work or input.

This trust can in turn be based on prior knowledge of the actor and prior vetting of other parts of their work or input.

That prior knowledge and vetting can also help the decision-maker know whether it’d be worth proactively reaching out to an actor about a given decision.

EA decision-makers are typically more likely to have prior knowledge or have already vetted EA actors than non-EA actors, or may find it easier to get that knowledge or do that vetting.[10]

Community-level trust, strong epistemics, and shared values

Arguably, EAs have “better epistemics” in various ways than many other knowledge communities.

For example, many other communities start with the assumption that the issue they work on is especially important, focus more than would be ideal on raising awareness and alarm relative to seeking truth, tend more towards those directions over time (for reasons related to echo chambers or “evaporative cooling of group beliefs”), or simply don’t think about prioritisation.[11]

But I acknowledge that similar issues also apply to parts of the EA community, and that it might be as true for EA as a whole as for a typical knowledge community.

More clearly, there is on average more alignment in values between EA than between EAs and non-EAs.

So it could often make sense for EAs to place somewhat more trust in EA (vs non-EA) work or inputs.

Reasoning transparency and related habits/norms seem more common within EA than outside of it. This means that, even setting aside the above points, it may often be easier to understand what, concretely, work or input by EAs implies, and how much weight to put on it, than would be the case for non-EA work.

Three paths to impact for the price of one

The same work or input that brings existing knowledge into EA may also address non-mainstream questions within mainstream topics (see above) and/or provide some better answers than existing work has on questions the existing work addresses (see below).

For simplicity, this section focused on knowledge, but essentially the same points could be made about theories, methodologies, techniques, heuristics, skills, ways of working, etc.; other communities have developed many examples of each of those things that could be usefully brought into the EA community.

2. Improve behaviours and decisions in other communities

The vast majority of what happens in the world is of course determined by decisions made outside of the EA community—by governments, think tanks, academics, voters, people deciding on careers, etc. And the more mainstream a topic is, the more actors outside of the EA community will tend to care about research on it. This would presumably tend to increase the expected amount of non-EA resources or other decisions (e.g., legislative or regulatory decisions) that research on such topics will influence, at least if we control for factors like how high-quality and strategic the research and dissemination was.

This influence could involve (a) improvements according to the non-EA decision-makers’ own goals or values and/or (b) improvements from an EA perspective. (The influence could also in some cases be negative from one or both of those perspectives.)

This influence could come from research on non-mainstream questions within mainstream topics (see section 1a) or from research that provides better answers that existing work has (see section 1b), as long as insights from that research are transmitted to decision-makers in other communities and influence their decisions. Or this influence could come from bringing existing knowledge, theories, methodologies, techniques, heuristics, skills, ways of working, etc. from the EA community into other communities, in a process mirroring that described in section 1c.

We could also perhaps think of this path to impact as including elements of field building and movement building, such as increasing non-EAs’ awareness of and inclination towards EA, or topics that seem important from an EA perspective, or ideas from the EA community, etc.

All that said, influencing a larger amount of non-EA resources or other decisions (e.g., legislative or regulatory decisions) must be traded off against:

Potentially having a more minor influence on each of those units of resources or on each decision than could be had for EA resources or decisions (due to EA researchers often being more trusted by EA decision-makers, having more shared values with them, etc.)

Influencing resources or decisions that may be focused on lower priority areas anyway

3. Build networks between EA and other communities

See also network building.

Researching relatively mainstream topics can help build knowledge of and connections in other communities which work on related issues. (And this is an advantage over researching less mainstream topics, precisely because those topics will touch on fewer or smaller communities.) The more EAs have such knowledge and connections, the better they—or the people they talk to—can recommend non-EA organisations, projects, job-seekers, experts, etc. for EAs to fund, work for, hire, get advice from, get mentorship from, etc. In addition to recommendations, they could also make introductions, make referrals, provide signal-boosts or put in a good word, and so on.[12]

This can overlap or aid with the paths to impact discussed above. For example, this can be seen as “researching” the very narrow, applied, non-mainstream question “Which organisations and experts should EAs funders consider funding or getting advice from?”, and as helping “busy deciders” find non-EAs they can trust the input of and/or delegate to.

And the information, referrals, etc. can also flow in the other direction. For example:

An EA building this knowledge and these connections could also help them recommend EA organisations, job-seekers, experts, etc. for non-EA people or organisations to fund, work for, hire, get advice from, get mentorship from, etc. And it could help them make introductions, referrals, etc. This can overlap or aid with the path to impact discussed in the next section.

In the process of an EA researching relatively mainstream topics, members of other communities may themselves gain more knowledge of and connections with that EA or other parts of the EA community, which could provide the same sorts of benefits discussed earlier in this section.

4. Equip the researchers for influential roles in other communities

As noted, the vast majority of what happens in the world is determined by decisions made outside of the EA community. And these decisions are often made poorly or in ways poorly aligned with EA values. Thus, EAs could often be impactful by filling and effectively using influential roles in other communities. (See also working at EA vs non-EA orgs and Dafoe’s (2020) “field building model of research”.)

EAs will be better able to do this if they acquire relevant knowledge, skills, connections, and credibility. Doing research on mainstream topics is often one effective way to acquire those things, and is sometimes the most effective way.[13]

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Avital Balwit, Spencer Becker-Kahn, Damon Binder, Marcus Davis, Juan Gil, Hamish Hobbs, Jennifer Lin, Fin Moorhouse, David Moss, David Reinstein, Luca Righetti, Ben Snodin, Peter Wildeford, and Linch Zhang for helpful comments on earlier drafts. This of course does not imply their endorsement of all aspects of this post.

Appendix: Notes on what I mean by “mainstream”?

In the Summary, I wrote “We could call a topic more ‘mainstream’ the less neglected it is; the more it overlaps with topics and fields that are established and of interest to many people outside the EA community or associated communities; and the more you’d expect that people outside those communities would care about the topic”.

By that definition, “mainstream-ness” actually collapses together three not-perfectly-correlated dimensions.

By “the more you’d expect that people outside [the EA and associated] communities would care about the topic”, I mean things like: “the more the topic seems like it would matter for the worldviews common outside of those communities, if the premises for why it would matter given a longtermist worldview are sound”.

For example, let’s say an intervention’s key claimed path to impact on the long-term future would flow through improving the near-term future for humans in a major way that doesn’t require particularly “speculative” reasoning. Then, if there’s sound reasoning behind that path to impact, you might expect many non-EAs and non-longtermists to care about the intervention. And if they don’t, that’s some evidence that the reasoning for the path to impact is bad.

In contrast, if an intervention’s key claimed path to impact wouldn’t involve near-term benefits to humans, or relies on particularly “speculative” reasoning, then it’d be less surprising if few non-EAs or non-longtermist EAs care about that intervention, and that’d provide less evidence that the reasoning for the path to impact is bad.

How “mainstream” a topic is can depend on precisely how you define the scope of that topic, and can vary greatly between a topic and some specific subtopics.

E.g., biology is more mainstream than pandemics, which is more mainstream than engineered pandemics, which is more mainstream than “large-scale risks from engineered pandemics”, and how mainstream that is depends on how high a bar we set for “large-scale”.

Relatedly, Wiblin (2016) writes: “A challenge of any framework of this kind will be that carefully chosen ‘narrow’ problems tend to do better than broadly defined ones. For example, ‘combating malaria’ will look more pressing than ‘global health’ because malaria is a particularly promising health problem to work on. Similarly, improving health in Kenya is going to look more impressive than improving health in Costa Rica. There’s nothing wrong with these findings – but they could create a misleading impression if a broadly defined problem is compared with a narrowly defined one. If someone were motivated they could make a problem look more or less pressing by defining it differently – and this is something to be aware of in interpreting these scores.”

Arguably, the first path to impact I discuss in this post could instead be described as “Focus on a non-mainstream, especially longtermism-relevant subtopic within a mainstream topic.”

- ↩︎

In this post, I’ll often use “the EA community” as shorthand for “the EA community and associated communities”, including communities such as the rationalist community, the longtermist community, the AI safety community, and the effective animal advocacy community. The latter communities heavily overlap with the EA community, and some are arguably entirely contained within the EA community.

- ↩︎

Another way to phrase the question: “How would this researcher add value, given that (a) there are already many experts working on related topics, (b) this researcher not an expert, and (c) this researcher intends to do relatively brief, generalist-style research, rather than developing expertise in a narrow subset of these topics?”

- ↩︎

But note that many projects will have impact via more than one of those paths, and sometimes it can be hard to distinguish between these paths.

- ↩︎

I’m using the term “EAs” as shorthand for “People who identify or interact a lot with the EA community or an associated community”; this would include some people who don’t self-identify as “an EA”.

- ↩︎

My thinking has been influenced by previous discussions of somewhat related issues, such as:

What’s the comparative advantage of longtermists? (see Crucial questions for longtermists, and see here for relevant quotes and sources)

How much impact should we expect longtermists to be able to have as a result of being more competent than non-longtermists? How does this vary between different areas, career paths, etc.?

How much impact should we expect longtermists to be able to have as a result of having ‘better values/goals’ than non-longtermists? How does this vary between different areas, career paths, etc.?

Discussions of epistemic modesty, ‘rationalist/EA exceptionalism’, and similar

- ↩︎

For example, having the paths to impact discussed in this post in mind might help you optimise for these paths to impact when making decisions about:

What topics and specific questions to research

How thoroughly/deeply to research each question

Target audiences, publication venues, and writing styles

- ↩︎

For example, one could argue that GiveWell is focused on relatively mainstream topics, has many researchers who lack backgrounds in developmental economics or other relevant fields, and often does relatively brief research projects, but that their work has been very useful despite this, for reasons including them tackling specific questions that differ from those tackled in existing work (e.g., questions about cost-effectiveness and room for more funding).

- ↩︎

For example, over the last 10 years, the resources dedicated to AI risk have increased much faster (in proportional terms) than the resources dedicated to authoritarianism risk or nuclear risk, meaning it’s now easier for factors such as personal fit to outweigh neglectedness when someone is deciding which of those topics they should work on.

- ↩︎

For prior discussion that’s somewhat relevant to this sort of work, see Research Debt, The Neglected Virtue of Scholarship, and Fact Posts: How and Why. For some things that I think serve as prior examples of this sort of work, see A Crash Course in the Neuroscience of Human Motivation, How to Beat Procrastination, The Best Textbooks on Every Subject, and much of Scott Alexander’s writing.

- ↩︎

It also may be more worthwhile for them to invest in learning about and vetting EA actors since a greater fraction of the work of those actors’ work may be relevant to the EA decision-maker (rather than their work just sometimes overlapping with EA priorities) and they may continue working on relevant areas for longer.

- ↩︎

Additionally, in some cases, they have conflicts of interest.

- ↩︎

There are many reasons this could be useful. One category of ways is discussed in Improving EAs’ use of non-EA options for research training, credentials, testing fit, etc.

- ↩︎

A reviewer of a draft of this post suggested that a good example of paths 3 and 4, and maybe 2, might be “The direction that AI safety has moved in in the last couple of years, with a lot more EAs doing legible ML work (both for plausibly EA-adjacent reasons like circuits/scaling laws and what seem to be non-EA, credential-building reasons) and getting employed at mainstream places”. This sounds about right to me.

- Every Forum Post on EA Career Choice & Job Search by (31 Oct 2025 20:23 UTC; 121 points)

- Nuclear risk research ideas: Summary & introduction by (8 Apr 2022 11:17 UTC; 103 points)

- 's comment on MichaelA’s Quick takes by (19 May 2021 15:29 UTC; 30 points)

- 's comment on Humanities Research Ideas for Longtermists by (19 Jun 2021 23:45 UTC; 8 points)

On the face of it, it seems like researching and writing about “mainstream” topics is net positive value for EAs for the reasons you describe, although not obviously an optimal use of time relative to other competing opportunities for EAs. I’ve tried to work out in broad strokes how effective it might be to move money within putatively less-effective causes, and it seems to me like (for instance) the right research, done by the right person or group, really could make a meaningful difference in one of these areas.

Items 2.2 and 2.3 (in your summary) are, to me, simultaneously the riskiest and most compelling propositions to me. Could EAs really do a better job finding the “right answers” than there are to be found in existing work? I take “neglectedness” in the ITN framework to be a heuristic that serves mainly to forestall hubris in this regard: we should think twice before assuming we know better than the experts, as we’re quite likely to be wrong.

But I think there is still reason to suspect that there is value to be captured in mainstream causes. Here are a few reasons I think this might be the case.

“Outcome orientation” and a cost-benefit mindset are surprisingly rare, even in fields that are nominally outcomes-focused. This horse has already been beaten to death, but the mistakes, groupthink, and general confusion in many corners of epidemiology and public health during the pandemic suggests that consequences are less salient in these fields than I would have expected beforehand. Alex Tabarrok, a non-epidemiologist, seems to have gotten most things right well before the relevant domain experts simply by thinking in consequentialist terms. Zeynep Tufekci, Nate Silver, and Emily Oster are in similar positions.

Fields have their own idiosyncratic concerns and debates that eat up a lot of time and energy, IMO to the detriment of overall effectiveness. My (limited) experience in education research and tech in the developed world led me to conclude that the goals of the field are unclear and ill-defined (Are we maximizing graduation rates? College matriculation? Test scores? Are we maximizing anything at all?). Significant amounts of energy are taken up by debates and concerns about data privacy, teacher well-being and satisfaction, and other issues that are extremely important but which, ultimately, are not directly related to the (broadly defined) goals of the field. The drivers behind philanthropic funding seem, to me, to be highly undertheorized.

I think philanthropic money in the education sector should probably go to the developing world, but it’s not obvious to me that developed-world experts are squeezing out all the potential value that they could. Whether the scale of that potential value is large enough to justify improving the sector, or whether such improvements are tractable, are different questions.

There are systematic biases within disciplines, even when those fields or disciplines are full of smart, even outcomes-focused people. Though not really a cause area, David Shor has persuasively argued that Democratic political operatives are ideological at the cost of being effective. My sense is that this is also true to some degree in education.

There are fields where the research quality is just really low. The historical punching bag for this is obviously social psychology, which has been in the process of attempting to improve for a decade now. I think the experience of the replication crisis—which is ongoing—should cause us to update away from thinking that just because lots of people are working on a topic, that means that there is no marginal value to additional research. I think the marginal value can be high, especially for EAs, who are constitutionally hyper-aware of the pitfalls of bad research, have high standards of rigor, and are often quantitatively sophisticated. EAs are also relatively insistent on clarity, the lack of which seems to be a main obstacle to identifying bad research.

Thanks for this comment. I think I essentially agree with all your specific points, though I get the impression that you’re more optimistic about trying to get “better answers to mainstream questions” often being the best use of an EA’s time. That said:

this is just based mainly on something like a “vibe” from your comment (not specific statements)

my own views are fairly tentative anyway

mostly I think people also need to consider specifics of their situation, rather than strongly assuming either that it’s pretty much always a good idea to try to get “better answers” on mainstream questions or that it’s pretty much never a good idea to try that

One minor thing I’d push back on is “especially for EAs, who are constitutionally hyper-aware of the pitfalls of bad research, have high standards of rigor, and are often quantitatively sophisticated.” I think these things are true on average, but “constitutionally” is a bit too strong, and there is also a fair amount of bad research by EAs, low standards of rigour among EAs, and other problems. And I think it’s importnat that we remember that (though not in an over-the-top or self-flagellating way, and not with a sort of false modesty that would guide our behaviour poorly).

To clarify, I’m not sure this is likely to be the best use of any individual EA’s time, but I think it can still be true that it’s potentially a good use of community resources, if intelligently directed.

I agree that perhaps “constitutionally” is too strong—what I mean is that EAs tend (generally) to have an interest in / awareness of these broadly meta-scientific topics.

In general, the argument I would make would be for greater attention to the possibility that mainstream causes deserve attention and more meta-level arguments for this case (like your post).

Above, I wrote “In many (but not all) cases, EAs could provide better answers than the existing work has on the same questions that the existing work aims to answer.” Here are some further points on that:

I’m not sure if this would be true in most cases, and I don’t think it’d be especially useful to figure out how often this is true.

I think it’s best if people just don’t assume by default that this can never happen or that it would always happen, and instead look at specific features of a specific case to decide how likely this is in that case.

Previous work on epistemic deference could help with that process.

I think even in some cases where EAs could provide better answers than existing work has, that wouldn’t be the best use of those EAs’ time—they may be able to “beat the status quo” by more, or faster, in some other areas.

One key reason why EAs could often provide better answers is that some questions that have received some non-EA attention, and that sit within mainstream topics, are still very neglected compared to their importance.[1]

For example, a substantial fraction of all work on Tetlock-style probabilistic forecasting was funded due to Jason Matheny (who has worked at FHI and has various other signals of strong EA-alignment), was funded by Open Philanthropy, and/or is being done by EAs.

A related point is that, although rational non-EA decision-makers would have incentives to reduce most types of existential risk, these incentives may be far weaker than we’d like because existential risk is a transgenerational global public good, might primarily be bad for non-humans, and might occur after these decision-makers lives or political terms are over anyway.

Another key reason why EAs could often provide better answers is that it seems many EAs have “better epistemics” than members of other communities, as discussed in section 1c.

The claims in this section are not necessarily more arrogant, insular, or epistemically immodest than saying that EAs can in some cases have positive counterfactual impact via things like taking a job in government and simply doing better than alternative candidates would at important tasks.

(That said, much or most of the impact of EAs taking such jobs may instead come from them doing different tasks, or doing them in more EA-aligned ways, rather than simply better ways.)

These claims are also arguably lent some credibility by empirical evidence of things like EAs often finding mainstream success in areas such as academia or founding companies (see also this comment thread).

[1] On the other hand, I think low levels of mainstream attention provide some outside-view evidence that the topic actually isn’t especially important. This applies especially in cases where the reasons EAs think the topics matter would also, if true, mean the topics matter according to more common “worldviews” (see the Appendix). But I think this outside-view evidence is often fairly weak, for reasons I won’t go into here (see epistemic deference for previous discussion of similar matters).

A possible fifth path:

Build the EA movement by creating additional entry points, increasing its surface area, and/or increasing the chance that EA has done some substantive work on whatever topic a given person is already interested in.

E.g., if EA had done no substantive work on climate change, that may have reduced the number of people who heard about it, or increase the number who heard about it, looked for work on climate change, saw that there was none, and thus felt that the community wasn’t for them, had bad priorities, or similar.

This overlaps with path 3 and to some extent paths 2 and 4.

On the other hand, I’d be wary of aiming explicitly for this path to impact.

In the case of climate change, it probably does make sense to do substantive work on it anyway (ignoring this path to impact), and (relatedly) it seems reasonable for many (but not most) EAs to prioritise climate change.

But we don’t want everyone to just stick with whatever priorities they happened to have before learning about EA.

If there’s a topic that it wouldn’t make sense to substantive work on if not for this path to impact, then maybe this path to impact wouldn’t be a good thing anyway.

Perhaps either we’d end up with people working on low-priority areas under an EA banner, perhaps rather than switching to higher-priority areas, or we’d end up with people feeling there was a “bait and switch” where they were attracted to EA for one reason and then told that that area is low-priority.

In any case, this path might be better handled by people who are explicitly focused on movement building, rather than people doing research.