Corporate Global Catastrophic Risks (C-GCRs)

Epistemic status

Very uncertain and speculative. I don’t excessively hedge my claims throughout for clarity’s sake (‘better wrong than vague’).

Summary

Are corporations causing global catastrophic risks (C-GCRs)?

Here, I argue for this to be true, based on the following claims:

Corporations grow ever larger over time.

Corporations grow exponentially more powerful over time.

Corporations cause exponentially more regulatory capture over time.

Corporations cause exponentially larger externalities over time.

If all these claims are true and cannot be falsified, then it follows that the externalities of big, powerful, unregulated corporations will increase over time to the level of GCRs.

I then argue for the following corollaries:

Corporations are already the distal cause and main driver of anthropogenic and emergent technological GCRs such as global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs).

C-GCRs are a bigger threat than GCRs from state actors.

C-GCR reduction is more effective than targeted GCR reduction because it is broader, large in scale, neglected, and solvable.

I suggest concrete policy proposals to reduce C-GCRs, by diversifying corporate ownership, enforcing corporate taxes, and optimizing funding for regulatory agencies.

1. Are corporations growing ever larger?

Economic theory suggests that corporations try to maximize profits. Incentives create strong selective pressure for corporations to grow (e.g. because they benefit from economies of scale).[1]

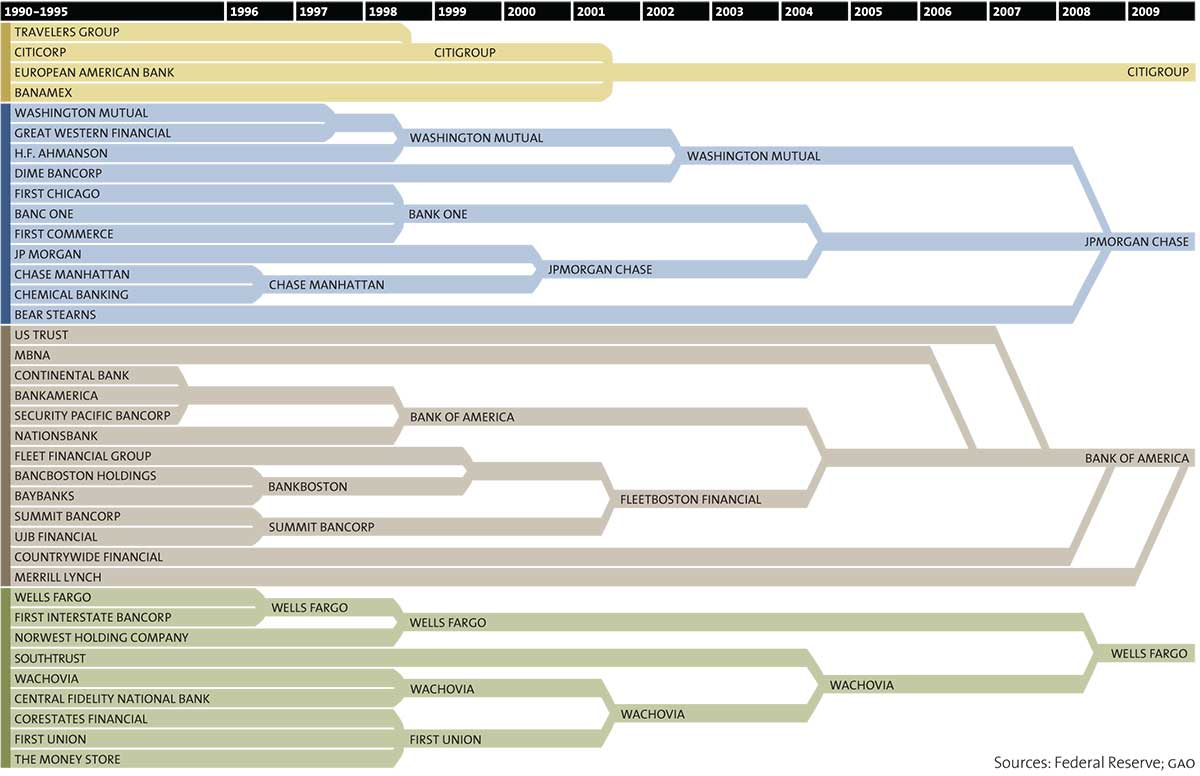

Empirically, corporations have become much bigger especially in the last ~20 years, because of cross-border mergers & acquisitions:[2]

Revenues of the Fortune 500 increased from 58% to 73% of US GDP

Bigger, Fortune 100, corps grew even faster: from 33% to 46% of GDP. Their share of Fortune 500 revenues increased from 57% to 63%.[3] Some of it due to increased revenues from abroad.

Of corporations with $1bn+ revenues the top 10% now capture 80% of profits—up 1.6x.[4]

Industries become “increasingly dominated by ‘superstar firms’ with high profits and a low share of labor in firm value-added and sales”.[5] For instance, Walmart has >2 million employees‚ FAANG corps only on the order of 100k.

Markups, the ratio of the price to the marginal cost of production, have also increased.

This trend should continue: some corporations’ market capitalizations are ~$1tn.[6] This is a proxy for market valuation—the discounted sum of all future profits. Profits and revenues correlate, so the market predicts that corporate revenues and thus power will increase. Multinationals can grow bigger than non-multinationals because of cross-border M&A.[7]

As a rule, corporations grow larger over time.

2. Do corporations optimize to become exponentially more powerful over time?

Power is roughly proportional to how many resources an agent has to achieve its goals.

Recently, researchers have proposed that states’ “budgets” (tax revenues) and corporations’ “budgets” (revenues minus their profits) are comparable in that they are crude, but useful proxies for their power (despite corporations and states spending on different things).[8]

For instance, Shell’s revenue/budget to sell fossil fuels is $272bn. About half of Boeing’s $96bn revenue comes from its defense contractor subsidiary—the amount of power to sell military equipment.

Big state actors (e.g. U.S., EU, China) have the biggest budgets (+$1tn).[9] But, surprisingly, some corporations now have ~$0.5tn budgets. Walmart has higher revenues than Spain or Australia and Apple has higher revenues than Belgium or Mexico. 71 out of the 100 most powerful actors are corporations with combined budgets of $10tn vs. $18tn in combined budgets of the 29 states (see Appendix; spreadsheet).

If a corporation spends just 0.1% of its $0.5tn annual budget on things that might cause negative externalities, this equates to $0.5bn. For instance, Apple spends >$1bn/year on marketing. Lobbying budgets could increase to a similar level.

Also, corporations sometimes combine their power. For instance, if lobbying for certain favorable regulations benefits a whole industry, this creates a free-rider problem. Corporations routinely solve this problem by sharing lobbying costs and throwing budgets together to fund industry bodies and trade associations. This way, corporations become even more powerful. In contrast, state power is curtailed by mandatory and entitlement spending taking up an increasing share of their budgets (e.g. >70% in the US).[10]

Overall, corporate power has increased to the level of many state actors.

3. Do corporations cause exponentially larger externalities over time?

As corporations grow, they create exponentially larger:

externalities, both positive and negative

consumer surplus, but also harm to consumers

Historically, big corporations robustly increased net social welfare—outweighing negative externalities.[11],[12],[13] Positive externalities: Larger corporations contribute disproportionately to the economic performance of countries—they are more productive, pay higher wages, enjoy higher profits and are more successful in international markets.[14] Uber’s easily quantifiable consumer surplus is ~$3bn.[15] Even the attention economy, vilified for wasting trillions in people’s time, might actually create billions in consumer surplus through more content and more efficient ads.[16]

But Big Business (such as Big Oil, Tobacco, Alcohol, Pharma, Food, Meat, Agro, Tech, Media, Finance), also creates increasingly negative externalities and harm consumers.

Empirically, we have seen Big Business increasingly playing a large part in the following negative externalities:

The Global Obesity Epidemic: 2 billion people are overweight[17] (though some costs are internalised by consumers)

The Global Tobacco Epidemic: 1 billion people might die prematurely[18] (though some costs are internalised by consumers)

Factory farms: 50 billion animals/year killed.[19]

2008 financial crisis: >100% GDP cost for the U.S. ($50k-$120k for every U.S. household) and caused 500k excess cancer-related deaths worldwide (through increased unemployment).[20],[21]

The prison-industrial complex incarcerates many people and lobbies[22] (but see [23])

Addictive technologies (e.g. social media, smartphones) affect billions and have been called an emerging public health problem.[24],[25]

In theory, corporate profit-maximization functions should correlate strongly with the social welfare maximization function. But if consumer choice does not correlate perfectly with (long-term average, total) utility (of all morally-relevant agents), then even a small divergence might result in side-effects causing large negative externalities. Because destroying value is easier than creating value, negative externalities can become very high as evidenced by the examples above. Consider climate change: this is not merely a coincidence, but the result of something inevitably causing harm as a by-product of ruthless optimization.

Thus, as a rule, as corporations grow they cause exponentially larger positive externalities, consumer surplus and utility, but also cause exponentially larger negative externalities, harm consumers and disutility.

4. Do corporations cause regulatory capture proportional to their size?

In economics, governments are to reduce businesses’ negative externalities via regulation. But governments are increasingly unable to regulate large corporations. Why?

Historically, corporate and state power was coupled, because corporate tax on profits increased government budgets proportionally. But average global corporate tax rates are decreasing, from 47% (GDP-weighted: 39%) in 1980 to only 23% (GDP-weighted: 26%) in 2018.[26] Corporations actively try to avoid taxes.[27]

Governments’ capacity to regulate has decreased: between 1979 and 2005, both US House committee and Government Accountability Office staff decreased by ~40%; Research Service staff, which provides nonpartisan policy analysis to lawmakers, by 20%.[28]

Corporations can use lobbying for regulatory capture[29]. The economics literature has long worried about increasing regulatory capture.[30] Generally, lobbying has increased in recent years[31]. In the US, corporations spend about $3bn/year lobbying the government[32]. In the EU, lobbying has also increased in recent years.[33] In particular, Big Tech’s and Finance’s lobbying budgets have increased.[34],[35]

In general, increasingly powerful corporations can promote their interests through lobbying and evade increasingly weak government regulation through regulatory capture.

5. Are anthropogenic and emergent technological GCRs a form of C-GCR?

Because humanity has survived for >200k years, natural GCRs (e.g. asteroids, pandemics) only have a 0.1%-1% risk of causing extinction per century. This might be 10x less than man-made GCRs (e.g. nuclear war, engineered bioweapons, AI, climate change).[36]

Corporations spend more on R&D than governments.[37] Generally, corporations are relevant actors in areas of anthropogenic GCRs from emerging technology such as risks from AI[38], GCBRs[39], climate change, and war.

Nuclear weapons: The U.S. plans to spend $1.7 trillion on nuclear weapons in the coming years[40]–a share of which will go to corporate contractors.

Bio-risk: Corporations have received billions in recent years to work on synthetic biology, a field changing the bio-economy, worth several trillions.[41],[42] Since 2001, US biodefense research spending has increased 20-fold, even though it does not (yet) meet the definition of a biomedical military–industrial complex.[43]

AI-risk: Corporations are the main driver of developments in AI and spend billions on R&D.[44] The level of technical AI expertise at leading AI labs is substantially higher than that within the US military.[45] Competitive pressure to develop AI is the only reason for AI risk because it takes away the option of slowing down AI development until we have a good solution to the alignment problem.[46]

Corporations also lobby on GCR-relevant issues:

Climate change: World Energy expenditure is in the trillions. [47],[48] Thus, it makes sense that fossil fuel companies have spent >$1Bn on misleading climate-related lobbying.[49] Climate change might be a GCR edge case: its direct effects might not be an x-risk, but its indirect effects could cascade to GCR-level given that there is a 10% risk of >6°C warming (see [50] for discussion).

Nuclear War / Great power war: Corporations are lobbying to get NATO countries to spend 2%/GDP on military.[51] The US ICBM program was partially created due to corporate lobbying.[52] Defense company Lockheed Martin has the second most lobbyists in DC (31 in-house lobbyists + 53 connections with lobbying firms).[53] In France, India, UK, and the US, corporations make atomic bombs.[54] Corporation made +$2bn in profit in the last 10 years, and there are many safety risks, while the National Nuclear Security Administration is understaffed.[55] China’s and Russia’s nuclear weapons programs are government-owned and controlled, but some talk about a Russian nuclear-industrial complex.[56]

Biorisk: Biotech-pharma has diluted the Biological Weapons Convention verification protocol and influenced the US to reject it.[57]

Other emerging tech: Fukushima has been cited as a case study for emergent technological GCRs: the Japanese nuclear sector had revolving doors to the regulator, “destined to result in [...] regulatory capture.” [58],[59]

Thus, corporations deserve special attention when horizon-scanning for emerging technological GCRs as they are their distal cause.

6. C-GCR reduction is more effective than targeted GCR from emerging tech reduction

Reducing C-GCRs is a more generalized intervention than targeted reduction of GCRs from emerging tech. Its broad cross-cutting nature makes it more effective.[60]

Because corporations will create as of yet unknown emerging tech that causes GCRs, C-GCR reduction is good for horizon-scanning and preventative GCR reduction. Regulators or altruists who focus on particular GCRs play Whac-A-Mole with corporations. Every industry can create its own GCR—for instance, see research on GCRs from chemicals.[61] Even if one is particularly concerned about just one GCR from say AI, C-GCR prevention is more effective than targeted GCR reduction, because the distal source of it comes from corporations.

What can be done? I go through some policies in the next sections.

7. Policy solutions to decrease corporate GCRs

1. Breaking up big corporations

Because corporations cause exponentially more disutility as they grow, breaking up big corporations (or preventing M&A) to lower their power would reduce the size of their externalities. But this is intractable, as countries will worry too much about their economic competitiveness. There is no consensus amongst economists on whether governments should regulate the size of big corporations more generally (e.g. through preventing M&A or breaking them up).[62],[63]

2. Increasing corporate taxes for bigger corporations

Corporate taxes have some advantages, but they are not usually considered to be Pigovian[64] (and might also have other drawbacks[65]). But in light of C-GCRs, corporate taxes become Pigovian because corporations are usually causing large externalities. Increasing (the progressiveness of) corporate taxes (i.e. the bigger the corporation the higher the tax)[66] might reduce C-GCRs.

But currently corporate tax is regressive. Why? Because bigger corporations are better at avoiding tax by shifting profits overseas, and thus have a lower tax rate than smaller firms.[67] A politically tractable solution might be to reduce corporate tax avoidance.

A solution might be to tax the self-assessed value of a corporation’s domestic legal entity. [68] At the self-assessed value would ba strike price that they’d be required to sell it to anyone. For instance, Apple pays little corporate tax in the UK, because Apple UK does not make a lot of profit. But getting Apple to give a true estimate of the value of Apple UK Ltd and putting say a 5% tax might be harder to avoid.

3. Mission hedging to fund regulators

A foundation whose mission is to stop climate change can invest their endowment using ‘mission hedging’ by investing in fossil fuel stocks.[69] This way it has more money to give to organizations that combat climate change when more fossil fuels are burned, fossil fuel stocks go up and climate change will get particularly bad. When fewer fossil fuels are burnt and fossil fuels stocks go down, the foundation will have less money, but it does not need the money as much. Generally, increasing investment in objectionable corporations creates a hedge around an actor’s mission, which sometimes, maximizes expected utility.[70]

Similarly, governments can use mission hedging to reduce C-GCRs. For instance, governments can set up a sovereign wealth fund that invests in an index fund that covers all corporations weighted by market capitalization or revenue. Dividends from individual corporate stocks could then be used to fund regulators so their budgets increase with corporate size. In other words, if Apple revenue/power increases and Apple stocks generate higher returns, this would increase the staff/budget of a department within a regulatory agency tasked with regulating Apple. Similarly, the sovereign wealth fund could also own stocks of foreign firms to fund intelligence agencies to monitor foreign corporations.

4. Diversifying corporate ownership through sovereign wealth funds and reducing home bias

If the ownership of corporations would be more diversified more, then there would be fewer incentives to create externalities. In other words, if everyone were a shareholder of Big Oil, then shareholder value might be maximized by reducing emissions. This is because both profits and negative externalities are shared more widely and nobody has an advantage from profiting from untaxed externalities.

This might also reduce arms races: if a technology’s up- and downsides are shared, then it decreases adversarialism and increases collaboration.[71] Relatively few individuals sometimes own and control major AI corps (FAANG).[72],[73] In contrast, ~25% of Baidu is owned by 10 Western funds (Vanguard, Blackrock, etc).[74]

Governments setting up sovereign wealth funds that invest in an index fund that covers all corporations weighted by market capitalization or revenue would diversify ownership.

This policy might be politically tractable. Countries such as China now allow fully foreign-owned enterprises,[75] increasing government-ownership of corporations has recently been suggested,[76] and sovereign wealth funds might increase tax receipts[77] and create a hedge against risks to the domestic economy. Note that governments being minority shareholders across an industry would be different from state-owned enterprises that often create more externalities than private firms.[78]

Another way to diversify ownership of corporations might be to reduce home bias, where countries and people hold suboptimal amounts of foreign equity. US investors have 78% of their equity portfolio in U.S. stocks, which are only a third of world market portfolio, by capitalization.[79] Reducing home bias as an intervention might be tractable because getting home biased investors to diversify ownership of corporations might also benefit them financially. This might be an alternative to windfall clauses.[80] Governments could grant tax incentives to their citizens invest in foreign equities or give incentives for diversifying their portfolio.

Coda: Are corporations optimization demons?

2.5bn years ago stromatolites changed the atmosphere from a CO2-rich to O2-rich through photosynthesis, because they had no competition.[81] A corporation might not be a superintelligence,[82] but it might create one. We should not let corporations lead on AI governance as has been suggested.[83] Usually, CSR/PR is relatively small relative to lobbying activities and externalities corporations create (e.g. fossil fuel companies will sometimes come out for a carbon tax, but then spend money on anti-climate lobbying; corporations will invest a small amount of money into AI safety but spend much more AI R&D).

In sum, I think it might be useful to think of corporations as dangerous optimization demons which will cause GCRs if left unchecked by altruism and philanthropy.[84]

Appendix: Top 100 state and corporate actor by revenue ≈ power

Adapted fromBarbic et al. “States versusCorporations”

References

[1] Breaking down the barriers to firm growth in Europe

[2] States versus Corporations

[3] FiveThirtyEight—Big Business Is Getting Bigger

[4] McKinsey Global Institute ‘Superstars’—The dynamics of firms, sectors, and cities leading the global economy

[5] David Autor—The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms

[6] List of public corporations by market capitalization

[7] List of multinational corporations—Wikipedia

[8] States versus Corporations

[9] Wikipedia — List of public corporations by market capitalization

[10] Wikipedia—US federal budget #Mandatory spending and entitlements

[11] Steven Pinker—Enlightenment Now

[14] Breaking down the barriers to firm growth in Europe

[15] Using Big Data to Estimate Consumer Surplus

[16] The Economics of Attention Markets

[17] Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years

[18] The Global Tobacco Epidemic

[19] Factory farming − 80,000 Hours

[20] Economic downturns, universal health coverage, and cancer mortality in high-income and middle-income countries, 1990–2010

[21] Financial crisis may have caused 500,000 cancer deaths worldwide: study

[22] Prison–industrial complex—Wikipedia

[23] Are private prisons driving mass incarceration?

[24] Problematic smartphone use: Digital approaches to an emerging public health problem

[26] Tax Foundation—Corporate Tax Rates Around the World

[27] Corporate Tax Avoidance Remains Rampant

[28] Lindsey—The Captured Economy

[29] Stigler—The Theory of Economic Regulation

[30] Regulatory Capture—A Review

[31] Modern Lobbying: A Relationship Market

[34] Google, Amazon, and Facebook all spent record amounts last year lobbying the US government

[35] Igan—Bank Lobbying: Regulatory Capture and Beyond

[36] Toby Ord — Will We Cause Our Own Extinction? Natural versus Anthropogenic Extinction Risks

[37] Global private and public R&D funding

[38] The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation

[39] Schoch-Spana et al. - Global Catastrophic Biological Risks: Toward a Working Definition

[40] Congress Of The United States Congressional Budget Office—Approaches for Managing the Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2017 to 2046

[41] Center for Biosafety Research and Strategy, Tianjin University, China — Synthetic biology: Recent progress, biosafety and biosecurity concerns, and possible solutions

[42] Synthetic Biology in the Driving Seat of the Bioeconomy

[43] A biomedical military–industrial complex?

[44] Artificial intelligence: The next digital frontier? - McKinsey

[45] 80000hours.org—US AI policy profile

[46] Thomas Sittler—A shift in arguments for AI risk

[47] World energy expenditures

[48] Energy expenditure, economic growth, and the minimum EROI of society

[49] Influencemap.org—Big Oil’s Real Agenda on Climate Change

[50] John Halstead—Is climate change an existential risk?

[51] Defense Contractors Say Russian Threat Is Great

[52] Who’s Really Driving Nuclear-Weapons Production?

[55] Light penalties and lax oversight encourage weak safety culture at nuclear weapons labs

[56] The Russian Nuclear-Industrial-Complex

[57] Unwarranted Influence? The Impact of the Biotech-Pharmaceutical Industry on U.S. Policy on the BWC Verification Protocol

[58] Classifying global catastrophic risks

[59] A Nuclear Complex? A Network Visualization of Japan’s Nuclear Industry and Regulatory Elite

[60] Nick Beckstead—A Proposed Adjustment to the Astronomical Waste Argument

[61] Global Catastrophic Risks from Chemical Contamination

[62] IGM Forum—Breaking Up Large Tech Companies

[63] IGM Forum—Breaking up European Champions

[65] Good recent review paper on corporate taxes effects

[66] Why isn’t the corporate income tax progressive?

[67] Corporate Tax Avoidance Remains Rampant

[68] Glen Weyl – Radical Markets

[69] Brigitte Roth Tran—Divest, Disregard, or Double Down?

[70] Hauke Hillebrandt—A generalized strategy of ‘mission hedging’

[71] Amanda Askell on the 80k podcast

[72] The Top 5 Google Shareholders

[73] The Top 6 Shareholders of Facebook

[75] China unveils draft law to allow fully foreign-owned enterprises

[76] Mariana Mazzucato—The Entrepreneurial State

[77] Paul Christiano on Sovereign Wealth Funds

[78] When Governments Regulate Governments

[79] Literature review on Home Bias

[80] Allen Defoe—AI Strategy, Policy, and Governance

[82] Corporations vs.superintelligences—Arbital

[83] Jade Leung—Why Companies Should be Leading on AI Governance

- Big List of Cause Candidates by (25 Dec 2020 16:34 UTC; 305 points)

- The $100trn opportunity: ESG investing should be a top priority for EA careers by (18 Mar 2021 13:54 UTC; 72 points)

- Why are we not talking more about the metacrisis perspective on existential risk? by (29 Jan 2023 9:35 UTC; 53 points)

- Latest EA Updates for June 2019 by (1 Jul 2019 10:07 UTC; 39 points)

- Clarifying existential risks and existential catastrophes by (24 Apr 2020 13:27 UTC; 39 points)

- AGI risk: analogies & arguments by (23 Mar 2021 13:18 UTC; 31 points)

- 's comment on Defining Meta Existential Risk by (9 Jul 2019 19:49 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Denise_Melchin’s Quick takes by (18 Sep 2020 15:33 UTC; 3 points)

- 課題候補のビッグリスト by (20 Aug 2023 14:59 UTC; 2 points)

Overall I thought this was a weak article. In many cases the reasoning seems to be ignorant of simple economics. Below I point out several issues; others I omitted in a vain attempt at brevity.

Corporate Growth

It is definitely true that there are incentives for firms to grow up the their efficient size. However, equally there are incentives not to grow further, and many companies are around these levels—for a little background on the theory see for example wikipedia. Certainly, when I was an equity analyst, when news one of my companies had just announced an acquisition crossed the tape, I’d expect the share price to be down on the news—whereas if they announced a spin-off, I’d expect the stock to be up!

This is very misleading.

We can see this by noting that, rather perversely, one of your proposed policies would actually increase corporate revenue as a % of GDP. Why? By breaking up vertically integrated companies, we would add a new layer of transactions that would be counted as revenue despite having no additional economic substance. If I have a solar panel factory and an installation business, no revenue is recorded when the panels move from the factory to the installation trucks, only when they go to the end customers. If you split my company into two, we now record revenue twice, despite no fundamental change—illustrating why this is a silly metric. It is more appropriate to compare profits to GDP, or revenue to gross transactions.

People more commonly look at S&P profits as a % of GDP, which is better, but still not great. You mention as an aside that this is partly due to international revenues, but without noting how this undermines the point. Over the last few decades we have seen considerable globalisation, as US companies have expanded into overseas markets, so this ratio would have increased even if the compositition of the domestic US economy remained totally unchanged.

One of the first lessons one learns in accounting analysis is that ratios have to make economic sense—the numerator and denominator have to refer to the same thing—which is not the case here. Instead we should be comparing domestic profits to GDP.

Why compare corporate revenue to state tax revenue?

One of the key parts of the argument is that we can meaningfully compare corporate revenue to state tax revenue as a measure of power. However the justification for this in the article is very weak:

How do this random PhD student researchers justify this approach?

That’s right—they basically just posit it. There is no actual justification for assuming that a company with revenues of $100bn is more powerful than a state with taxes of $90bn.

It makes sense that there is no justification—because the statement is clearly absurd. Consider the example from the article: comparing the Australian State to Walmart, the latter of which is supposedly more powerful.

Australia has a powerful military, including ten frigates, two destroyers and six submarines. Their air force has over 100 combat planes, and they have 30,000 active soldiers in the military. Using this they have participated in a number of wars. In contrast, to my knowledge Walmart has zero frigates, zero destroyers, zero submarines, and zero combat planes.

In the event of a war, furthermore, the Australian government might be able to introduce conscription, dramatically increasing their manpower. Walmart is unlikely to be able to do so as they have no such legal authority.

With the benefit of these weapons, the Australian government is able to achieve a great deal. For example, they are able to force almost every single Australian to pay them taxes. In contrast, Walmart is reliant on people voluntarily giving them money, has to offer merchandise in return, and is unable to imprison people who refuse. Speaking of which, the Australian government has around 40,000 people in prison—Walmart conspicuously lacks its own prison system. Even in cases where someone directly steals from them, Walmart is forced to rely on the assistance of the US government to deal with the situation.

Finally, the Australian state is able to effectively bar large groups of people from entering its territory on the basis of their nationality, potentially imprisoning them for long periods on remote islands to achieve this. In contrast, Walmart’s ability to prevent peaceful people from entering its stores is extremely limited.

This article, however, rather than interrogating the claim that corporate revenues can be directly compared to state taxes, instead accepts it completely. In the space of a few short paragraphs we move from proposing it as an interesting idea to accepting it as the basis for claims like:

And some of the claims made in this section are simply bizarre. For example,

Where does this number come from? I checked their 2018 numbers on bloomberg and got revenue of $388bn. More importantly, revenue is not at all the same thing as ‘budget to sell fossil fuels’. That would be part of SG&A, which is obviously much smaller—around $11bn. Instead, most of their revenue is spent buying physical inputs for e.g. their refining business.

Or take this one:

According to OpenSecrets, the largest US corporate spender on lobbying in 2018 was Alphabet (Google), spending just under $23m. It is technically true that their budget could increase to over a billion; however, this would require a >33,000% increase.

Or this claim:

This spending is not really mandatory at all—if states did not want to give out benefits there is no requirement for them to do so. We know this is true because there have been many powerful states that spent very little on benefits. If states are weakened by entitlement spending, it is because they choose to do so.

In contrast, corporations have to spend the vast majority of their revenue on raw resources, salaries etc. in order to produce the goods and services they sell. Buying potatoes is not optional for McDonalds!

Do corporations cause exponentially larger externalities over time?

This sections seems like a random grab-bag of complaints with a lack of model-based thinking. In particular, there doesn’t seem to be any reason to think that externalities grow exponentially, except that corporates (and the economy as a whole) grow exponentially. The difference between externalities growing exponentially relative to corporate size, and externalities remaining fixed relative to corporate size, might seem like a trivial point, but one of the proposed ‘solutions’ - to break up large corporations—actually ends up resting on this confusion.

Firstly we should note that the citations mentioned do not actually support the article’s point:

The linked polls discuss specific government interventions in specific cases, as is standard in the antitrust literature, not general regulation of corporate size. I am not aware of any credible economists who believe in a carte blanche restriction on the size of corporations. I have literally never heard any economist suggest a policy which would restrict companies that have grown organically due to economies of scale and good execution, like Netflix or Apple.

But more importantly, breaking large corporates up into smaller pieces would only reduce externalities if those externalities were super-linear in corporate size. This doesn’t seem to be the case however—if you split up corporation with two factories, you still have two companies with one factory each, producing just as much pollution in total. (They might even produce slightly more as smaller firms are often slower to adopt new technologies).

The article might also have benefited from discussion of the track records of non-capitalist systems, like the pointless slaughter caused by the soviet whale quota system. The article mentions Fukushima… but not Chernobyl, despite the latter being an example of much worse behaviour. Similarly, it blames corporates for obesity, but does not mention the difficulties communist states had in avoiding mass starvation. Nor at these problems only in socialist countries—for example, even in the US privately-run power plants are cleaner than those run by the government:

It is not possible to reduce corporate power in a vacuum—the proposed solutions largely instead transfer it to governments. But given that, even according to the bizarre revenue=tax methodology adopted, states were still more powerful than their corporations, this would mean concentrating more power in the most powerful entities. Entities which in the past have repeatedly brought mankind to the brink of nuclear war—an externality far greater than that of any mere corporation.

Many thanks for your kind feedback. I thought your review and deconstruction of the issues were excellent and I concur with many points that you make. I have updated the Google Doc version of the manuscript that I believe you also kindly commented on. I might update this post to reflect this if I choose to do another version of this post.

Please see my inline response below.

You are absolutely right that I ignored mentioning that there are indeed some incentives for corporations not to grow further. However, overall, I think on net incentives to grow are slightly stronger than to stay at the current size, as evidenced by growth in corporate size.

I’m really sorry for being unclear: I did not actually propose breaking up corporations, because I do not think it’s politically tractable. I merely mention it because people will probably think about this.

I’m sorry I was being unclear here — the point here is not the size of states relative to their domestic firms, but the size of the largest corporations (proxied by the Fortune, even though Fortune Global would be better) and the largest state actors (the US).

I agree that the authors of that paper could have provided more reasoning on the measure and source they cite (you there original source is here). I absolutely agree that better measures of corporate power are conceivable — however I only found this one dataset.

However, I feel like there’s something to be said for using revenues instead of profits. As I write, the revenue is the budget a corporation has to fulfill its goal (often to sell things), which I had defined as being roughly proportional to its power. Profits usually benefit shareholders and not the corporate entity itself. There are corporations might have high profits but that are somewhat small and can’t use much revenues to fulfil its objectives.

You also outline some very telling differences between Australia and Walmart that I absolutely agree with. However, there might be more similarities between corporations and states that it might at first superficially appear. For instance, yes states ‘can imprison people’, yet, corporations can decide on supply chains and effectively keep many people in modern slavery.

I did mention that “corporate revenue is a crude, but useful proxies for their power (despite corporations and states spending on different things).” My thinking here was “All models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Sorry I did postulate that I use revenue as a proxy for power, but have changed this (will be reflected in a future version of this doc). I did optimize for brevity while writing and so I agree that the reasoning can move quite fast, and a future version could benefit from much more hedging.

I’m sorry I should have cited this more clearly—this is from the paper I cite, which is based on the Fortune Global 2017.

That’s an excellent point—fixed costs for buying physical inputs can significantly curtail corporate power. I agree that ‘budget to sell fossil fuels’ was poorly worded. What I meant by that is the budget available to get fossil fuels to the consumer (which includes extraction of fossil fuels etc.).

Yes, I do cite numbers on lobbying expenditures, and agree that they are not as big yet. My point was merely that in theory there is a potential for large increases. In fact, corporations might spend significantly more—as your source suggests: https://www.opensecrets.org/dark-money

In staunchly democratic states where many people receive entitlements, political realities being what they are, it is difficult, but agreed, not impossible, for states to cut spending.

I do agree that in some cases externalities might not increase with corporate size. However, because bigger corporations have bigger economies of scale, and one big corporation is often better at increasing consumer surplus and growth, they should also be ‘better’ at explointing profits from untaxed externalities. My intuitions here might be bias me though because I have never understand why anyone would want to fight 1 horse sized duck, effectively a dinosaur, as opposed to 100 tiny duck sized horses.

My agenda was probably a bit simpler than you might have supposed – I just wanted to highlight that there might be something about corporate power that needs altruists attention.

I wholeheartedly agree that non-capitalist system are strictly worse than capitalist ones and have cited evidence that corporations do a huge amount of good in the world.

Although my agenda was fairly simple, the issues raised may well require more serious consideration – of the sort that you have offered.

You might be surprised to hear that I consider my own political leanings very free market.

I’m not denying that reducing ill-effects from socialist systems (see Venezuela) still deserve a lot of attention.

However, I think it’s a false dichotomy that we cannot worry about the ill effects that socialism can have while at the same time seriously considering whether corporations can have increasingly ill effects as well and perhaps deserve more regulation/attention.

My policy solutions come in different flavors. True, the sovereign wealth fund idea would be more statist, but with minimal government interference in the market. Tax incentives for private individuals would be a more market-y solution, even though that too is technically state interference.

I agree that states have historically created more risks (such as nuclear war), however, I myself was quite surprised by the evidence of corporate influence when it comes to nuclear war. In particular, the dilution of the Biological Weapons Convention protocol by the bio industry. I would want altruists to look into this more.

Let me start by agreeing that the people of Venezuela are in deep distress, and ill served by the ruling government.

I am not a fan of -isms and labels. Is public education socialist? how about public universal healthcare (like in Europe or Japan)? North Korea calls itself DPRK (Democratic.. Republic) I laugh at it and don’t take it seriously, why should we take it seriously when Venezuela claims that it is socialist? Anyway what do broad terms like socialism and capitalism mean? When did USA become capitalist? How about Britain? India? China? South Africa? Guatemala? Socialist/communist/capitalist institutions are steeply hierarchical and with few exceptions have male leaders, likewise kingdoms before that were male led and steeply hierarchical. I see more similarities between the various -isms than differences.

I think the world we see today is an effect of industrialization, and the political systems today are reflections of that, on an evolutionary substrate of human behavior that is atleast a million years in the making.

==== added later ====

sigh the questions are serious ones, if downvoting please tell me why either via private message or as a reply

Thanks

I downvoted the post because I didn’t learn anything from it that would be relevant to a discussion of C-GCRs (it’s possible I missed something). I agree that the questions are serious ones, and I’d be interested to see a top level post that explored them in more detail. I can’t speak for anyone else on this, and I admit I downvote things quite liberally.

Wouldn’t this be likely to substantially increase regulatory capture, and open the door to stronger negative externalities? It seems like you’re describing a situation in which governments’ and regulators’ budgets are in part set by the profits of the companies they’re meant to regulate, so some government employees might genuinely have reason to worry that them doing their job properly could make their job less secure (by decreasing the profits that ultimately help fund their salaries).

And for similar reasons, people might feel that being more lax with such regulations could increase the chances they get promotions, pay rises, bonuses, etc., again because it would increase their employers budgets.

And this could all be especially pronounced for the top decision-makers in the relevant departments or regulatory bodies, who I imagine (though I could be wrong) are evaluated at least in part by their departments’ budgets.

In theory, yes you’re right there might be a perverse incentive.

But in practice I don’t think it’ll be very pronounced, because regulators do not have that much influence on a corporation.

Also the individuals regulator’s salaries are not directly tied to stock dividends of the corporations they regulate, but rather the absolute amount of staff in a team tasked with regulating a particular corporation or sector within a larger government agency.

On the individual level promotions, pay rises, bonuses, and other incentives should still be based on what we’re ultimately want regulators to do: reducing negative externalities and increasing positive externalities (i.e. performance reviews, doing good work).

Adding more checks and balances (e.g. journalism, watchdogs, critical think tanks, red teaming within government) might be better than what we have now.

I agree that those incentives should be based on what we want regulators to do. And I don’t think the salaries would be explicitly tied to stock dividends of the corporations they regulate. But the profits of those corporations would affect the budgets of the regulators, which seems like it could in practice influence salaries, incentives, etc. If we’re already facing a notable amount of regulatory capture, then clearly things like oversight are not fully keeping regulators aligned with what we want them to do. And my guess, though again it’s not based on much, is that the effect of “intensifying perverse incentives for regulators, as long as no one’s looking too closely” would be greater than the effect of “sometimes providing additional resources for regulators”.

I guess another reason that might be so is that the potential for perverse incentives could always be there, whereas the additional resources only kick in when a company actually does provide more dividends, which is probably correlated pretty well but not perfectly with power, which is correlated pretty well but not perfectly with negative externalities.

And another might be that it seems like limited resources is just one problem, and I’m not sure it’s the main one. My very vague impression is that the concern is often more about the corruption or capture of regulators. So it seems like that proposed intervention might target the smaller cause of the problem, while potentially exacerbating the larger cause.

Thanks for the comments… I think you’re generally raising a bunch of valid points.

A few more thoughts on this:

First, perverse incentives are already present within the current system. Indeed, they’re likely ubiquitous and inherent in any optimization process—it’s just a matter of how powerful they are and the scale.

There is already a lot of regulatory capture and “revolving doors” between regulators and industry (c.f. 2008). In theory, nuclear regulators should want the nuclear industry to flourish, because their job and job prospects depend on it. In practice, it seems hard for me to see how implementing this would increase perverse incentives. Again, if you do this on an industry wide basis (the department of nuclear security is funded by an ETF of nuclear companies), it seems hard to see how regulators can substantially affect the stock movements of a whole industry.

It seems like a related but slightly separate problem.

Also note that this strategy is neutral wrt the absolute level of funding of the regulators. Rather it helps with prioritization within regulation (i.e. the government can buy $10bn or $100bn in stocks and disburse them to fund regulators).

And then it can’t do all the prioritization without human input: perhaps we do not need to regulate the $4 trillion global restaurant industry as much as the $4 trillion dollar global chemical industry. But I think there’s currently not much quantitative prioritization going on wrt how much regulation capacity should be assigned to different companies within an industry. So this is just to finesse current funding levels.

Second, generally, I slightly disagree that limited resources for regulators is not one of the major problem (again see 2008 - where regulators are always way behind industry in terms of staff, resources, analytic capacity, etc. - the same seems to be true for the tech industry, where there aren’t sufficient funds to hire top talent with deep understanding of the sector). Again, this strategy doesn’t really speak to the absolute amount we should spend on regulation—just that it’s a better way to cut the pie.

Hm… but I actually just had another idea of how to fund regulators perhaps reducing perverse incentives and also optimizing more for negative externalities.

Consider that the EU has fined Google $10bn. I think currently this is disbursed to go into the general budget.

But maybe one could buy Google stocks (or a technology ETF) with that money and use the dividends to fund digital regulation.

This way regulators would be incentivized to reduce negative externalities (through fining companies and the industry), but then also they’d be held back to completely wreck industries or companies, because they’re financed by the overall health of the industry after the fine.

I don’t think your comparison between corporations and governments is quite fair. Governments can influence a larger amount of revenue than just their own through regulation of companies. So some people have compared the GDP of countries to the revenue of corporations. But then the problem is that GDP is calculated by value add, and the value add of a corporation is significantly lower than their revenue (because they are paying for other companies’ products and services).

Yes, that’s a interesting point.

However, I think given that there’s a lot of regulatory capture going on, it is increasingly hard for governments to influence large amounts of corporate revenue, and corporations should work actively against this. This is evidenced by states being increasingly unable to collect corporate taxes.

Also, even if there’s some truth to it and states control some corporate revenue, then this might be offset to an extent by state power being curtailed by mandatory and entitlement spending taking up an increasing share of their budgets (e.g. >70% in the US).

I’ve seen countries’ GDP being compared colloquially to corporate revenue, but have never seen a paper on this. Do you know of one?

In terms of value added vs. revenue as a measure of corporate power—I think value added doesn’t quite capture it, because a high revenue, low value add company (think: Walmart) might still have substantial influence due to economies of scale of their lobbying (even if they just spend a small percentage of their overall revenue on this, it will be quite high).

Is it meaningful to say that some companies are growing exponentially when the markets they take part in are growing exponentially? https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/world-gdp-over-the-last-two-millennia?time=1913..2015

After a quick Google, Microsoft was $500bn market cap in it’s 2000 peak and now is about $1tn, but world GDP has almost doubled in that time also (60tn → 110tn).

Great point.

I think it makes sense:

Revenues of the Fortune 500 increased from 58% to 73% of US GDP

Bigger, Fortune 100, corps grew even faster: from 33% to 46% of GDP. Their share of Fortune 500 revenues increased from 57% to 63%

That means that the larger the corporation the larger its growth.

Great post. Also, I expected that Meditation on Moloch would be mentioned.

For those who haven’t read the Meditation, it’s a discussion of ways in which competitive pressures push civilizations into situations where almost all of our energy and happiness are eaten up by the scramble for scarce resources.

(This is a very brief summary that leaves out a lot of important ideas, and I recommend reading the entire thing, despite its formidable length.)

I was only interested in regulatory capture, so I only read point number 4. I saw some evidence that regulatory capture is increasing, but no support for your statement that this increase is exponential.

Yes, good point—I have not modelled this with actual data. There are some other ways of how corporations influence the political process e.g. through think tank funding as well (https://www.necir.org/investigations/think-tank-viz/).

I meant that lobbying spend seems to be not increasing linearly with inflation or GDP, but lobbying spending becoming a bigger and bigger share of GDP.

Evidence about this from my citations:

“Lobbying by banks increased in absolute terms over most of this time period, rising from a trough of $36.3 million in 1999 to a peak of $88.2 million in 2014. When scaled by the industry valueadded (i.e., gross domestic product-by-industry), this pattern remains largely unchanged (see Figure 2).”

“Google, Amazon, and Facebook all spent record amounts last year lobbying the US government

They spent a combined $48 million — up 13 percent from 2017″

also see this graph:

https://lobbyfacts.eu/charts-graphs

if you were to smooth it and perhaps squint your eyes a bit you might see a something hyperlinear / exponential there instead of a linear trend.

But see this graph which paints a different picture:

https://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/

I’ll revisit this claim in the next version of the paper.

I agree with most of the text, though with the same epistemic status. Nevertheless, I fear sovereign funds and government investment might affect free trade and create an incentive for big companies to corrupt political power, competing for its support, and for corrupt politicians to use this power for their own benefit. This may seem easy to avoid through good institutional design, but since we cannot even avoid regulatory capture, nor tax avoidance...