Improving the future by influencing actors’ benevolence, intelligence, and power

This post was written for Convergence Analysis. Some of the ideas in the post are similar to and/or draw influence from earlier ideas and work.[1]

Overview

This post argues that one useful way to come up with, and assess the expected value of, actions to improve the long-term future is to consider how “benevolent”, “intelligent”, and “powerful” various actors are, and how various actions could affect those actors’ benevolence, intelligence, and power. We first explain what we mean by those terms. We then outline nine implications of our benevolence, intelligence, power (BIP) framework, give examples of actions these implications push in favour of or against, and visually represent these implications.

These implications include that it’s likely good to:

Increase actors’ benevolence.

Increase the intelligence of actors who are sufficiently benevolent

Increase the power of actors who are sufficiently benevolent and intelligent

And that it may be bad to:

Increase the intelligence of actors who aren’t sufficiently benevolent

Increase the power of actors who aren’t sufficiently benevolent and intelligent

For example, depending on the details, it may be:

Good to fund moral philosophy research

Good to provide information about emerging technologies to policymakers who want to benefit all countries and generations

Bad to provide such information to somewhat nationalistic or short-sighted policymakers

Good to help policymakers gain political positions and influence if they (a) want to benefit all countries and generations and (b) understand the arguments for mitigating risks from emerging technologies

Bad to help policymakers gain political positions and influence if they (a) want to benefit all countries and generations but (b) think that that requires accelerating technological progress as much as possible

An additional implication of the BIP framework is that the goodness or badness of an increase in an actor’s benevolence, intelligence, or power may often be larger the higher their levels of the other two factors are.

(Throughout this post, we use the term “actors” to mean a person, a group of people of any size, humanity as a whole, or an “institution” such as a government, company, or nonprofit.[2])

Introduction

Let’s say you want to improve the expected value of the long-term future, such as by reducing existential risks. Which of the actions available to you will best achieve that goal? Which of those actions have major downside risks, and might even make the future worse?

Answering these questions precisely and confidently would require long-term predictions about complex and unprecedented events. Luckily, various frameworks, heuristics, and proxies have been proposed that help us at least get some traction on these questions, so we can walk a fruitful middle path between analysis paralysis and random action. For example, we might use the importance, tractability, and neglectedness (ITN) framework, or adopt the heuristic of pursuing differential progress.

This post provides another framework that we believe will often be useful for coming up with, and assessing the expected value of, actions to improve the long-term future: the benevolence, intelligence, power (BIP) framework.

What this framework is useful for

We think it will often be useful to use the BIP framework if one of your major goals in general is improving the expected value of the long-term future (see also MacAskill), and either of the following is true:

You’re trying to come up with actions to improve the long-term future.

You’re considering taking an action which isn’t specifically intended to improve the long-term future, but which is relatively “major” and “non-routine”, such that it could be worth assessing that action’s impacts on the future anyway

For example, the BIP framework may be worth using when coming up with, or considering taking, actions such as:

Starting a new organisation

Setting up a workshop for AI researchers

Choosing a career path

Donating over a thousand dollars

Writing an article that you expect to get a substantial amount of attention

The BIP framework could help you recognise key considerations, decide whether to take the action, and decide precisely how to execute the action (e.g., should you target the workshop at AI researchers in general, or at AI safety researchers in particular?).

Also note that the BIP framework is best at capturing impacts that occur via effects on other actors’ behaviours. For example, the framework will better capture the impacts of (a) writing a blog post that influences what biotech researchers work on and how they do so than (b) actually designing a vaccine platform oneself.[3] But this seems only a minor limitation, as it seems most actions to improve the long-term future would do so largely via affecting how other actors behave.

Finally, note that BIP is just one framework. It will often be useful to additionally or instead use other frameworks, heuristics, or proxies, and/or a more detailed analysis of the specifics of the situation at hand. For example, even if the BIP framework suggests action X would, in the abstract, be better than action Y, it’s possible your comparative advantage would mean it would be better for you to do action Y.

The three factors

This section will clarify what we mean, in the context of the BIP framework, by the terms benevolence, intelligence, and power. Three caveats first:

Our usage of these terms differs somewhat from how they are used in everyday language.

The three factors are also somewhat fuzzy, they overlap and interact in some ways,[4] and each factor contains multiple, meaningfully different sub-components.

The purpose of this framework is not to judge people, or assess the “value” of people, but rather to aid in prioritisation and in mitigating downside risks, from the perspective of trying to improve the long-term future. As the Centre for Effective Altruism notes in relation to a similar model, variation in the factors they focus on:

often rests on things outside of people’s control. Luck, life circumstance, and existing skills may make a big difference to how much someone can offer, so that even people who care very much can end up having very different impacts. This is uncomfortable, because it pushes against egalitarian norms that we value. [...] We also do not think that these ideas should be used to devalue or dismiss certain people, or that they should be used to idolize others. The reason we are considering this question is to help us understand how we should prioritize our resources in carrying out our programs, not to judge people.[5]

Benevolence

By benevolence, we essentially mean how well an actor’s moral beliefs or values align with the goal of improving the expected value of the long-term future. For example, an actor is more “benevolent” if they value altruism in addition to self-interest, or if they value future people in addition to presently living people.

Given moral and empirical uncertainty, it can of course be difficult to be confident about how well an actor’s moral beliefs or values align with improving the long-term future. For example, how much should an actor value happiness, suffering reduction, preference satisfaction, and other things?[6] But we think differences in benevolence can sometimes be relatively clear and highly important.[7] To illustrate, here’s a list of actors in approximately descending order of benevolence:

Someone purely motivated by completely impartial altruism (including considering welfare and suffering to be just as morally significant no matter when or where it occurs)

Someone mostly motivated by mostly impartial altruism

A “typical person”, who acts partly out of self-interest and partly based on somewhat altruistic “common sense” values

An unusually mean or self-interested person

Terrorists, dictators, and actively sadistic people[8]

We do not include as part of “benevolence” the quality of an actor’s empirical beliefs or more “concrete” values or goals. For example, one person may focus on supporting existential risk reduction (either directly or via donations), while another focuses on supporting advocacy against nuclear power generation. If both actors are similarly motivated by doing what they sincerely believe will benefit future generations, they may have the same level of benevolence; they are both trying to advance “good” moral beliefs or values. However, one person has developed a better plan for helping; they have identified a better path towards those “good” moral beliefs or values.[9][10] This likely reflects a difference in the actors’ levels of “intelligence”, in our sense of the term, which we turn to now.

Intelligence

By intelligence, we essentially mean any intellectual abilities or empirical beliefs that would help an actor make and execute plans that are aligned with the actor’s moral beliefs or values. Thus, this includes things like knowledge of the world, problem-solving skills, ability to learn and adapt, (epistemic) rationality, foresight or forecasting abilities, ability to coordinate with others, etc.[11][12] For example, two actors who both aim to benefit future generations may differ in whether their plan for doing so involves supporting existential risk reduction or supporting advocacy against nuclear power, and this may result from differences in (among other things):

how much (mis)information they’ve received about existential risks and interventions to mitigate them, and about the benefits and harms of nuclear power

how capable they are of following complex and technical arguments

how much they tend to critically reflect on arguments they’re presented with

That was an example where more “intelligence” helped an actor make high-level plans that were better aligned with the actor’s moral beliefs or values. Intelligence can also aid in making better fine-grained, specific plans, or in executing plans. For example, if two actors both support existential risk reduction, the more “intelligent” one may be more likely to:

identify what the major risks and intervention options are (rather than, say, focusing solely and uncritically on asteroids)

form effective strategies and specific implementation plans (rather than, say, having no real idea how to start on improving nuclear security)

predict, reduce, and/or monitor downside risks (rather than, say, widely broadcasting all possible dangerous technologies or applications that they realise are possible)

arrive at valuable, novel insights

But intelligence is not the only factor in an actor’s capability to execute its plans; another key factor is their “power”.

Power

By power, we essentially mean any non-intellectual abilities or resources that would help an actor execute its plans (e.g., wealth, political power, persuasive abilities, or physical force). For example, if two actors both support existential risk reduction, the more “powerful” one may be more able to actually fund projects, actually build support for preferred policies, or actually increase the number of people working on these issues. Likewise, if two actors both have malevolent goals (e.g., aim to become dictators) or both have benevolent goals but very misguided plans (e.g., aim to advocate against nuclear power), the more “powerful” actor may be more able to actually set their plans in motion, and may therefore cause more harm.[13]

Intelligence also aids in executing plans, and to that extent both “intelligence” and “power” could be collapsed together as “capability”. But there’s a key distinction between intelligence and power: differences in intelligence are more likely to also affect what plans are chosen, rather than merely affecting how effectively plans are carried out. Thus, as we discuss more below, it is more robustly valuable to increase actors’ intelligence than their power, since increasing a misguided but benevolent actor’s intelligence may help them course-correct, whereas increasing their power may just lead to them travelling more quickly along their net negative path.[14]

An analogy to illustrate these factors

We’ll use a quick analogy to further clarify these three factors, and to set the scene for our discussion of the implications of the BIP framework.

Imagine you’re the leader of a group of people on some island, and that all that really, truly matters is that you and your group make it to a luscious forest, and avoid a pit of lava.

In this scenario:

If you’re quite benevolent, you’ll want to help your group get to the forest.

If instead you’re less benevolent, you might not care much about where you and your group get to, or just care about whether you get to the forest, or even want your group to end up in the lava.

If you’re quite benevolent and intelligent, you’ll have a good idea of where the forest and the lava are, come up with a good path to get to the forest while avoiding the lava, and have intellectual capacities that’ll help with solving problems that arise as you travel that path.

If instead you’re quite benevolent but less intelligent, you might have mistaken beliefs about where the forest or lava are (perhaps even believing the forest is where the lava actually is, and thus leading your group there, despite the best of intentions). Or you might come up with a bad path to the forest (perhaps even one that would take you through the lava). Or you might lack the intellectual capacities required to solve problems along the way

If you’re quite benevolent, intelligent, and powerful, you’ll also have the charisma to convince your group to follow the good path you’ve chosen, and the strength, endurance, and food supplies to physically walk that path and support others in doing so.

If instead you’re quite benevolent and intelligent but less powerful, you might lack those capacities and resources, and therefore your group might not manage to actually reach the end of the good path you’ve chosen.

Implications and examples

We’ll now outline nine implications of the BIP framework. These can be seen as heuristics to consider when coming up with, and assessing the expected value of, actions to improve the long-term future, or “major” and “non-routine” actions in general. We’ll also give examples of actions these heuristics may push in favour of or against. Many of these implications and examples should be fairly intuitive, but we think there’s value in laying them out explicitly and connecting them into one broader framework.

Note that we don’t mean to imply that these heuristics alone can determine with certainty whether an action is valuable, nor whether it should be prioritised relative to other valuable actions. That would require also considering other frameworks and heuristics, such as how neglected and tractable the action is.

Influencing benevolence

1. From the perspective of improving the long-term future, it will typically be valuable to increase an actor’s “benevolence”: to cause an actor’s moral beliefs or values to better align with the goal of improving the expected value of the long-term future.[15]

Examples of interventions that might lead to increases in benevolence include EA movement-building, research into moral philosophy or moral psychology, creating materials that help people learn about and reflect on arguments for and against different ethical views, and providing funding or training for people who implement those kinds of interventions. Althaus and Baumann’s discussion of interventions to reduce (or screen for) malevolence is also relevant.

2. That first implication seems robust to differences in how “intelligent” and “powerful” the actor is. That is, it seems increasing an actor’s benevolence will very rarely decrease the value of the future, even if the actor’s levels of intelligence and power are low.

3. It will be more valuable to increase the benevolence of actors who are more intelligent and/or more powerful. For example, it’s more valuable to cause a skilled problem-solver, bioengineering PhD student, senior civil servant, or millionaire to be highly motivated by impartial altruism than to cause the same change in someone with fewer intellectual and non-intellectual abilities and resources. This is because how good an actor’s moral beliefs or values are is especially important if the actor is very good at making and executing plans aligned with those moral beliefs or values.

This suggests that, if one is considering taking an action to improve actors’ benevolence, it could be worth trying to target this towards more intelligent and/or more powerful actors. For example, this could push in favour of focusing EA movement-building somewhat on talented graduate students, successful professionals, etc. (Though there are also considerations that push in the opposite direction, such as the value of reducing actual or perceived elitism within EA.)

Influencing intelligence

4. It will often (but not always) be valuable to increase an actor’s “intelligence”, because this could:

Help an actor which already has good plans make even better plans, and/or execute their plans more effectively

Help an actor with benevolent values but misguided and detrimental plans realise the ways in which those plans are misguided and detrimental, and thus make better plans

Examples of interventions that might lead to increases in intelligence include funding scholarships, providing effective rationality training, and providing materials that help people “get up to speed” on areas like AI or biotechnology.

5. But it could be harmful (from the perspective of improving the long-term future) to increase the “intelligence” of actors which are below some “threshold” level of benevolence. This is because that could help those actors more effectively make and execute plans that are not so much “misguided” as “well-guided towards bad goals”. (See also Althaus and Baumann.)

For a relatively obvious example, it seems harmful to help terrorists, authoritarians, and certain militaries better understand various aspects of biotechnology. For a more speculative example, if accelerating AI development could increase existential risk (though see also Beckstead), then funding scholarships for AI researchers in general or providing materials on AI to the public at large might decrease the value of the long-term future.

Determining precisely what the relevant “threshold” level of benevolence would be is not a trivial matter, but we think even just recognising that such a threshold likely exists may be useful. The threshold would also depend on the precise type of intelligence improvement that would occur. For example, the same authoritarians or militaries may be “sufficiently” benevolent (e.g., just entirely self-interested, rather than actively sadistic) that improving their understanding of global priorities research is safe, even if improving their understanding of biotech is not.

6. More generally, increases in an actor’s “intelligence” may tend to be:

More valuable the more benevolent the actor is

More valuable the more powerful the actor is, as long as the actor meets some “threshold” level of benevolence

More harmful the more powerful the actor is, if that threshold level of benevolence is not met

Therefore, for example:

It may be worth targeting scholarship funding, effective rationality training, or educational materials towards people who’ve shown indications of being highly motivated by impartial altruism (e.g., in cover letters or prior activities).

It may be more valuable to provide wealthy, well-connected, and/or charismatic people with important facts, arguments, or training relevant to improving the future, rather than to provide those same things to other people.

If a person or group seems like they might have harmful goals, it seems worth being especially careful about helping them get scholarships, training, etc. if they’re also very wealthy, well-connected, etc.

Influencing power

7. It will sometimes be valuable to increase an actor’s “power”, because this could help an actor which already has good plans execute them more effectively. Examples of interventions that would likely lead to increases in power include helping a person invest well or find a high-paying job, boosting national or global economic growth (this boosts the power of many actors, including humanity as a whole), helping a person network, or providing tips or training on public speaking.

8. But it could be harmful (from the perspective of improving the long-term future) to increase the “power” of actors which are below some “threshold” combination of benevolence and intelligence. This is because:

That could help those actors more effectively execute plans that are misguided, or that are “well-guided towards bad goals”

That wouldn’t help well-intentioned but misguided actors make better plans (whereas increases in intelligence might)

This makes increasing an actor’s power less robustly positive than increasing the actor’s intelligence, which is in turn less robustly positive than increasing their benevolence.

For a relatively obvious example, it seems harmful to help terrorists, authoritarians, and certain militaries gain wealth and political influence. For a more speculative example, if accelerating AI development would increase existential risk, then helping aspiring AI researchers or start-ups in general gain wealth and political influence might decrease the value of the future.

As with the threshold level of benevolence required for an intelligence increase to be beneficial, we don’t know precisely what the required threshold combination of benevolence and intelligence is, and we expect it will differ for different precise types of power increase (e.g., increases in wealth vs increases in political power).

9. More generally, increases in an actor’s “power” may tend to be:

More valuable the more benevolent the actor is

More valuable the more intelligent the actor is, as long as the actor meets some “threshold” combination of benevolence and intelligence

More harmful the more intelligent the actor is, if that threshold combination of benevolence and intelligence is not met

Therefore, for example:

It seems better to help people, companies, or governments get money, connections, influence, etc., if their values are more aligned with the goal of improving the long-term future.

It seems best to provide grant money to longtermists whose applications indicate they have strong specialist and generalist knowledge, good rationality and problem-solving skills, good awareness of downside risks such as information hazards and how to avoid them, etc.

If a person or group seems like they might have harmful goals, it seems worth being especially careful about helping them get money, connections, influence, etc. if they also seem highly intelligent.

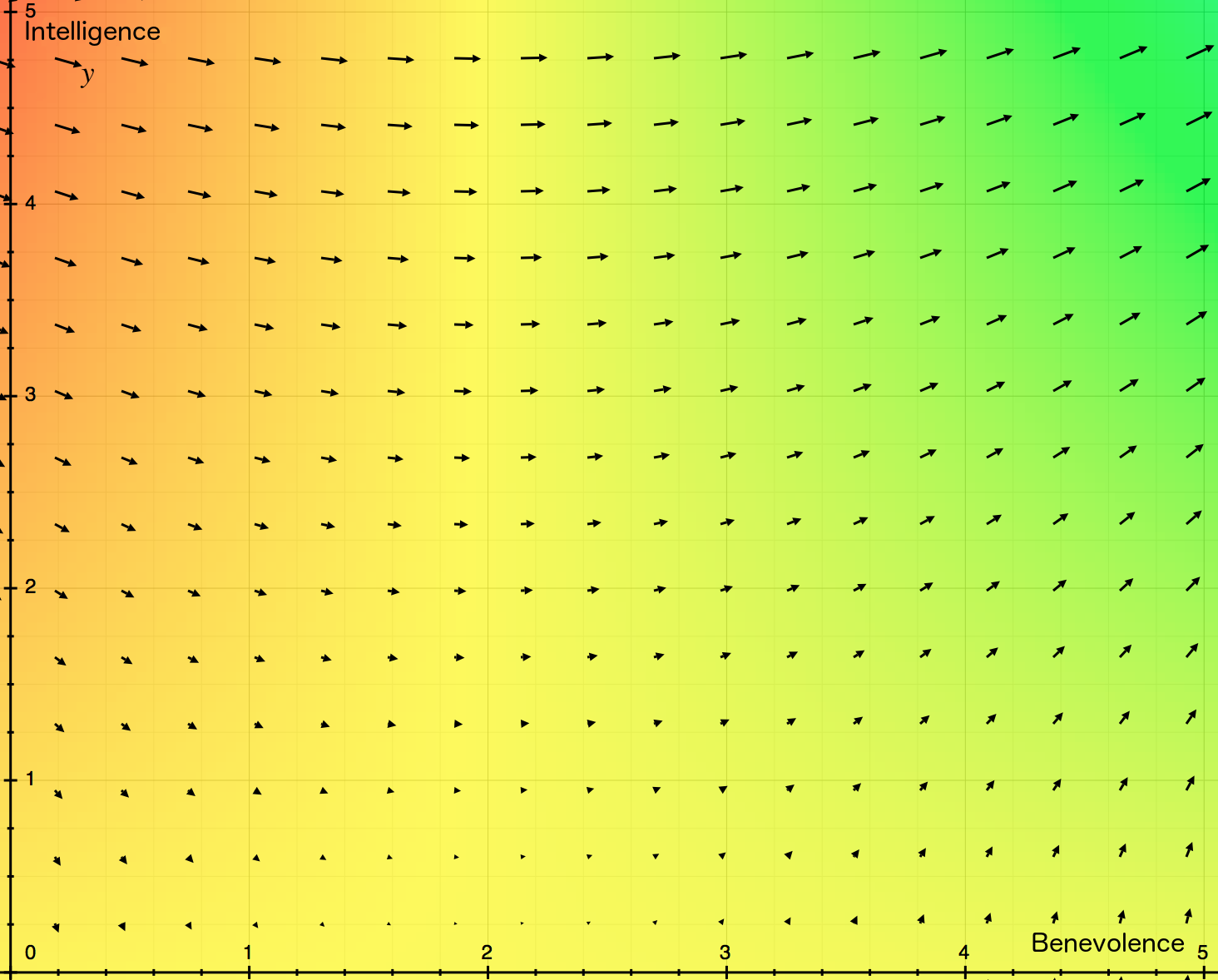

Visualising the implications of the BIP framework

We could approximately represent these implications using three-dimensional graphs, with benevolence, intelligence, and power on the axes, and higher expected values of the long-term future represented by greener rather than redder shades. To keep things simple and easy to understand in a still image, we’ll instead provide a pair of two dimensional graphs: one showing benevolence and intelligence, and the other showing a “combination of benevolence and intelligence” (which we will not try to precisely define) and power. The implications are similar for each graph’s pair of dimensions. Thus, again for simplicity, we’ve used two graphs that are mathematically identical to each other; they just have different labels.

We’ll also show a vector field on each graph (see also our post on Using vector fields to visualise preferences and make them consistent). That is, we will add arrows at each point whose direction represents which direction it would be beneficial to move in that point, and whose size represents how beneficial movement in that direction would be.[16]

Here is the first graph:

This graph captures the implications that:

Increases in benevolence seem unlikely to ever be harmful (the arrows never point to the left)

Increases in intelligence can be either harmful or beneficial, depending on the actor’s benevolence (the arrows on the left point down, and those on the right point up)

Changes in benevolence matter more the more intelligent the actor is (the arrows that are higher up are larger)

This graph does not capture the relevance of the actor’s level of power. Our second graph captures that, though it loses some of the above nuances by collapsing benevolence and intelligence together:

This second graph is mathematically identical to the first graph, and has similar implications.

Conclusion

The BIP (benevolence, intelligence, power) framework can help with coming up with, or assessing the expected value of, actions to improve the long-term future (or “major” and “non-routine” actions in general). In particular, it suggests nine specific implications, which we outlined above and which can be summarised as follows:

It may be most robustly or substantially valuable to improve an actor’s benevolence, followed by improving their intelligence, followed by improving their power (assuming those different improvements are equally tractable).

It could even be dangerous to improve an actor’s intelligence (if they’re below a certain threshold level of benevolence), or to improve their power (if they’re below a certain threshold of benevolence, or a certain threshold combination of benevolence and intelligence).

A given increase in any one of these three factors may often be more valuable the higher the actor is on the other two factors (assuming some threshold level of benevolence, or of benevolence and intelligence, is met).

We hope this framework, and its associated heuristics, can serve as one additional, helpful tool in your efforts to benefit the long-term future. We’d also be excited to see future work which uses this framework as one input in assessing the benefits and downside risks of specific interventions (including but not limited to those interventions briefly mentioned in this post).

This post builds on earlier work by Justin Shovelain and an earlier draft by Sara Haxhia. I’m grateful to Justin, David Kristoffersson, Andrés Gómez Emilsson, and Ella Parkinson for helpful comments. We’re grateful also to Andrés for work on an earlier related draft, and to Siebe Rozendal for helpful comments on an earlier related draft. This does not imply these people’s endorsement of all of this post’s claims.

- ↩︎

In particular, the following ideas and work:

The model of “three obstacles to doing the most good” discussed in this talk by Stefan Schubert

A model/metaphor discussed from 3:55 to 8:15 of this talk by Jade Leung

The Centre for Effective Altruism’s “three-factor model of community building”. (Roughly speaking, “benevolence” in this article’s framework is similar to parts of “dedication” and “realization” in that model, and “intelligence” and “power” here are similar to parts of “resources” and “realization” in that model.)

Differential progress / intellectual development / technological development

Nick Beckstead’s comments on slide 30 of this presentation about “broad” vs “targeted” attempts to shape the far future

The “research spine of effective altruism”, as discussed in this post

(We had not yet watched the Schubert and Leung talks when we developed the ideas in this post.)

- ↩︎

It’s worth noting that a group’s benevolence, intelligence, or power may not simply be the sum or average of its members’ levels of those attributes. For example, to the extent that a company has “goals”, its primary goals may not be the primary goals of any of its directors, employees, or stakeholders. Relatedly, it may be harder to assess or influence the benevolence, intelligence, or power of a group than that of an individual.

- ↩︎

That said, the framework may still have the ability to capture more “direct” impacts, or to be adapted to do so. For example, one could frame vaccine platforms as improving the long-term future by reducing the levels of intelligence and power that are required to mitigate biorisks, and increasing the levels of intelligence and power is required to create biorisks. One could even frame this as “in effect” increasing the intelligence and/or power of benevolent actors in the biorisk space, and “in effect” decreasing the intelligence and/or power of malevolent actors in that space.

- ↩︎

For example, increasing an actor’s benevolence and intelligence might increase their prestige, one of two main forms of status (see The Secret of Our Success). Both forms of status would effectively increase an actor’s power, as they would increase the actor’s ability to influence others.

- ↩︎

- ↩︎

Arguably, taking moral uncertainty seriously might itself be one component of benevolence, such that more benevolent actors will put more effort into figuring out what moral beliefs and values they should have, and will be more willing to engage in moral trade.

- ↩︎

It can also be hard to be confident even about whether improving the long-term future should be our focus. But this post takes that as a starting assumption.

- ↩︎

See also the discussion of “Dark Tetrad” traits in Reducing long-term risks from malevolent actors.

- ↩︎

This distinction between “moral beliefs or values” and “plans” can perhaps also be thought of as a distinction between “relatively high-level / terminal / fundamental goals or values” and “relatively concrete / instrumental goals or values”.

- ↩︎

We use advocacy against nuclear power generation merely as an example. Our purpose here is not really to argue against such advocacy. If you believe such advocacy is net positive and worth prioritising, this shouldn’t stop you engaging with the core ideas of this post. For some background on the topic, see Halstead.

- ↩︎

Note that, given our loose definition of intelligence, two actors who gain the same intellectual ability or empirical belief may gain different amounts of intelligence, if that ability or belief is more useful for one set of moral beliefs or values than for another. For example, knowledge about effective altruism or global priorities research may be more useful for someone aiming to benefit the world than someone aiming to get rich or be spiteful, and thus may improve the former type of person’s intelligence more.

- ↩︎

Thus, what we mean by “intelligence” will not be identical to what is measured by IQ tests.

See Legg and Hutter for a collection of definitions of intelligence. We think our use of the word intelligence lines up fairly well with most of these, such as Legg and Hutter’s own definition: “Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments.” However, that definition, taken literally, would appear to also include “non-cognitive” capabilities and resources, such as wealth or physical strength, which we instead include as part of “power”. (For more, see Intelligence vs. other capabilities and resources.)

Our use of “intelligence” also lines up fairly well with how some people use “wisdom” (e.g., in Bostrom, Dafoe, and Flynn). However, at times “wisdom” seems to also implicitly include something like “benevolence”.

- ↩︎

Note that the way we’ve defined “power” means that the same non-intellectual ability or resource may affect one actor’s power more than another, as it may be more useful given one plan than given another. See also footnote 11, the concept of asymmetric weapons, and Carl Shulman’s comment (which prompted me to add this footnote).

- ↩︎

One caveat to this is that actors may be able to use certain types of power to, in effect, “buy more intelligence”, and thereby improve how well-aligned their plans are with their goals. For example, the Open Philanthropy Project can use money to hire additional research analysts and thereby improve their ability to determine which cause areas, interventions, grantees, etc. they should support in order to best advance their values.

- ↩︎

As noted in footnote 7, there is room for uncertainty about whether we should focus on the goal of improving the long-term future in the first place. Additionally, improving benevolence may often involve moral advocacy, and there’s room for debate about how important, tractable, neglected, or “zero- vs positive-sum” moral advocacy is (for related discussion, see Christiano and Baumann).

- ↩︎

Both graphs are of course rough approximations, for illustrative purposes only. Precise locations, numbers, and intensities of each colour should not be taken too literally. We’ve arbitrarily chosen to make each scale start at 0, but the same basic conclusions could also be reached if the scales were made to extend into negative numbers.

- Are we neglecting education? Philosophy in schools as a longtermist area by (30 Jul 2020 16:31 UTC; 69 points)

- Improving science: Influencing the direction of research and the choice of research questions by (20 Dec 2021 10:20 UTC; 65 points)

- Potentially great ways forecasting can improve the longterm future by (14 Mar 2022 19:21 UTC; 43 points)

- Famine deaths due to the climatic effects of nuclear war by (14 Oct 2023 12:05 UTC; 40 points)

- Addressing Global Poverty as a Strategy to Improve the Long-Term Future by (7 Aug 2020 6:27 UTC; 40 points)

- How valuable is ladder-climbing outside of EA for people who aren’t unusually good at ladder-climbing or unusually entrepreneurial? by (1 Sep 2021 0:47 UTC; 39 points)

- Mind Enhancement Cause Exploration by (12 Aug 2022 5:49 UTC; 39 points)

- How might better collective decision-making backfire? by (13 Dec 2020 11:44 UTC; 37 points)

- Factors other than ITN? by (26 Sep 2020 4:34 UTC; 35 points)

- Mind Enhancement: A High Impact, High Neglect Cause Area? by (24 Mar 2022 20:33 UTC; 29 points)

- Aligning AI by optimizing for “wisdom” by (LessWrong; 27 Jun 2023 15:20 UTC; 28 points)

- 's comment on The case of the missing cause prioritisation research by (18 Aug 2020 17:36 UTC; 26 points)

- Key characteristics for evaluating future global governance institutions by (4 Oct 2021 19:44 UTC; 24 points)

- Keep humans in the loop by (LessWrong; 19 Apr 2023 15:34 UTC; 23 points)

- Information hazards: Why you should care and what you can do by (LessWrong; 23 Feb 2020 20:47 UTC; 18 points)

- 's comment on MichaelA’s Quick takes by (8 Sep 2020 9:06 UTC; 17 points)

- How Money Fails to Track Value by (LessWrong; 2 Apr 2022 12:32 UTC; 17 points)

- 's comment on Everyday Longtermism by (4 Jan 2021 2:58 UTC; 12 points)

- 's comment on EA Organization Updates: July 2020 by (26 Aug 2020 6:57 UTC; 12 points)

- 's comment on The community’s conception of value drifting is sometimes too narrow by (4 Sep 2020 7:42 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on “Good judgement” and its components by (20 Aug 2020 13:47 UTC; 8 points)

- 's comment on Some background for reasoning about dual-use alignment research by (LessWrong; 5 Jul 2023 11:59 UTC; 7 points)

- 's comment on The case of the missing cause prioritisation research by (23 Aug 2020 8:32 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Thoughts on “The Case for Strong Longtermism” (Greaves & MacAskill) by (3 May 2021 6:47 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Are we neglecting education? Philosophy in schools as a longtermist area by (2 Aug 2020 14:21 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on The community’s conception of value drifting is sometimes too narrow by (5 Sep 2020 7:18 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on When you plan according to your AI timelines, should you put more weight on the median future, or the median future | eventual AI alignment success? ⚖️ by (LessWrong; 5 Jan 2023 12:09 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on Possible gaps in the EA community by (24 Jan 2021 9:00 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Mind Enhancement Cause Exploration by (20 Sep 2022 22:21 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Convergence thesis between longtermism and neartermism by (3 Jan 2022 5:29 UTC; 2 points)

- 's comment on Open Thread: July—September 2023 by (19 Aug 2023 3:35 UTC; 1 point)

Thanks for the post. One concern I have about the use of ‘power’ is that it tends to be used for fairly flexible ability to pursue varied goals (good or bad, wisely or foolishly). But many resources are disproportionately helpful for particular goals or levels of competence. E.g. practices of rigorous reproducible science will give more power and prestige to scientists working on real topics, or who achieve real results, but it also constraint what they can do with that power (the norms make it harder for a scientist who wins stature thereby to push p-hacked pseudoscience for some agenda). Similarly, democracy increases the power of those who are likely to be elected, while constraining their actions towards popular approval. A charity evaluator like GiveWell may gain substantial influence within the domain of effective giving, but won’t be able to direct most of its audience to charities that have failed in well powered randomized control trials.

This kind of change, which provides power differentially towards truth, or better solutions, should be of relatively greater interest to those seeking altruistic effectiveness (whereas more flexible power is of more interest to selfish actors or those with aims that hold up less well under those circumstances). So it makes sense to place special weight on asymmetric tools favoring correct views, like science, debate, and betting.

Right, so instead of (or maybe in addition to) giving flexible power to supposedly benevolent and intelligent actors (implication 3 above), you create structures, norms, and practices which enable anyone specifically to do good effectively (~give anyone power to do what’s benevolent and intelligent).

Excellent points, Carl. (And Stefan’s as well.) We would love to see follow-up posts exploring nuances like these, and I put them into the Convergence list of topics worth elaborating.

Yes, I definitely think this is true. And thanks for the comment!

I’d say that similar is also true for “intelligence”. We use that term for “intellectual abilities or empirical beliefs that would help an actor make and execute plans that are aligned with the actor’s moral beliefs or values”. Some such abilities and beliefs will be more helpful for actors with “good” moral beliefs or values than for those with less good ones. E.g., knowledge about effective altruism or global priorities research is likely more useful for someone who aims to benefit the world than for someone who aims to get rich or be sadistic. (Though there can of course be cases in which knowledge that’s useful for do-gooders is useful for those trying to counter such do-gooders.)

I allude to this when I write:

I also alluded to something similar for power, but apparently only in a footnote:

One other thing I’d note is that things that are more useful for pursuing good goals than bad ones will, by the uses of terms in this post, increase the power of benevolent actors more than that of less benevolent actors. That’s because we define power in relation to what “help[s] an actor execute its plans”. So this point was arguably “technically” captured by this framework, but not emphasised or made explicit. (See also Halffull’s comment and my reply.)

I think this is an important enough point to be worth emphasising, so I’ve added two new footnotes (footnotes 11 and 13) and made the above footnote part of the main-text instead. This may still not sufficiently emphasise this point, and it may often be useful to instead use frameworks/heuristics which focus more directly on the nature of the intervention/tool/change being considered (rather than the nature of the actors it’d be delivered to). But hopefully this edit will help at least a bit.

Did you mean this was a concern about how this post uses the term power, or about how power (the actual thing) is used by actors in the world?

Thank you for the work put into this.

I can imagine a world in which the idea of a peace summit that doesn’t involve leaders taking mdma together is seen as an ‘are you even trying’ type thing.

This is an interesting framework. I think that it might make sense to think of the actors incentives as part of its benevolence; An academic scientist (or academia as a whole) has incentives which are aimed at increasing some specific knowledge which in itself is broadly societally useful (because that’s how funding is supposed to incentives them). Outside incentives might be more powerful than morality, especially in large organisations.

Good point! Yes, I think incentives are definitely important, and that the best way to fit them into this framework is within the “benevolence” component. Here’s how I’d now explain why incentives should be part of benevolence:

“We write in the post:

Acting based on incentives implies that the actor effectively has the “moral” belief or value that they should act based on incentives. This is similar to prioritising self-interest over altruism, to the extent that pursuing incentives benefits oneself and may sometimes be at odds with benefitting others (or the long-term future).”

But to be honest, I feel like it’s not a super clean fit. It might be better if this framework made it more explicit and intuitive how the first factor captures things like what the actor’s incentives are, and to what extent the actor is influenced by those incentives (vs their more clearly “moral” beliefs and values).

In earlier drafts, I’d written:

Perhaps that phrasing would’ve made it more clear that benevolence can include incentives.

Also, your comment, or the process of replying to it, makes me realise that I haven’t made it entirely clear where something like “willpower” fits into this framework. I think I’d put willpower under “power”, as it helps an actor execute its plans. But willpower could also arguably fit under “benevolence”, as an actor’s willpower will change what moral beliefs or values they in effect act as though they have.

I think that’s a good example of a way that BIP overlap. Also, intelligence and power clearly change benevolence by changing incentives or view of life or capability of making an impact. (Say, economic growth has made people less violent)

Indeed. One thing that’s true is that many actions will “directly” affect more than just one of the three factors, and another thing (which is what you mention) is that effects on one factor may often then have second-order effects on one or both of the other factors.

This is great! Was trying to think through some of my own projects with this framework, and I realized I think there’s half of the equation missing, related to the memetic qualities of the tool.

1. How “symmetric” is the thing I’m trying to spread? How easy is it to use for a benevolent purpose compared to a malevolent one?

2. How memetic is the idea? How likely is it to spread from a benevolent actor to a malevolent one.

3. How contained is the group with which I’m sharing? Outside of the memetic factors of the idea itself, is the person or group I’m sharing with it likely to spread it, or keep it contained.

(My opinions, not necessarily Convergence’s, as with most of my comments)

Glad to hear you liked the post :)

One thing your comment makes me think of is that we actually also wrote a post focused on “memetic downside risks”, which you might find interesting.

To more directly address your points: I’d say that the BIP framework outlined in this post is able to capture a very wide range of things, but doesn’t highlight them all explicitly, and is not the only framework available for use. For many decisions, it will be more useful to use another framework/heuristic instead or in addition, even if BIP could capture the relevant considerations.

As an example, here’s a sketch of how I think BIP could capture your points:

1. If the idea you’re spreading is easier to use for a benevolent purpose than a malevolent one, this likely means it increases the “intelligence” or “power” of benevolent actors more than of malevolent ones (which would be a good thing). This is because this post defines intelligence in relation to what would “help an actor make and execute plans that are aligned with the actor’s moral beliefs or values”, and power in relation to what would “help an actor execute its plans”. Thus, the more useful an intervention is for an actor, the more it increases their intelligence and/or power.

2. If an idea increases the intelligence or power of whoever receives it, it’s best to target it to relatively benevolent actors. If the idea is likely to spread in hard-to-control ways, then it’s harder to target it, and it’s more likely you’ll also increase the intelligence or power of malevolent actors, which is risky/negative. This could explain why a more “memetically fit” idea could be more risky to spread.

3. Similar to point 2. But with the addition of the observation that, if it’d be harmful to spread the idea, then actors who are more likely to spread the idea must presumably be less benevolent (if they don’t care about the right consequences) or less intelligent (if they don’t foresee the consequences). This pushes against increasing those actors’ power, and possibly against increasing their intelligence (depending on the specifics).

But all that being said, if I was considering an action that has its impacts primarily through the spread of information and ideas, I might focus more on concepts like memetic downside risks and information hazards, rather than the BIP framework. (Or I might use them together.)

Finally, I do think it could make sense for future work to create variations or extensions of this BIP framework which do more explicitly incorporate other considerations, or make it more useful for different types of decisions. And integrating the BIP framework with ideas from memetics could be one good way to do that.

EDIT: I’ve now made some edits to this post (described in my reply to Carl Shulman’s comment) that might go a little way towards making this sort of thing more explicit.

I found this post really interesting—thank you!

One question I have after reading is the tractability of increasing benevolence, intelligence, and power. I get the sense that increasing benevolence might be the least tractable (though 80,000 Hours seems to think it might still be worth pursuing), though I’m less sure about how intelligence and power compare. (I’m inclined to think intelligence is somewhat more tractable, but I’m highly uncertain about that.)

I think that this is a really important question. Relatedly, I’d suggest that the BIP framework is best used in combination with the ITN framework/heuristic. In particular, I’d want to always ask not just “What does BIP say about how valuable this change in actors’ traits would be?”, but also “How tractable and neglected is causing that change?”

But I think that, when asking that sort of question, I’d want to break things down a bit more than just into the three categories of increasing benevolence vs intelligence vs power.

For a start, increasing intelligence and power could sometimes be negative (or at least, that’s what this post argues). So we should probably ask about how tractable and neglected good benevolence, intelligence, or power increases are. In the case of intelligence and power, this might require only increasing specific types of intelligence and power, or increasing the intelligence and power of only certain actors. This might reduce the tractability of good intelligence/power increases, potentially making them seem less tractable than benevolence increases, even if just increasing someone’s intelligence/power in some way is more tractable.

And then there’s also the fact that each of those three factors has many different sub-components, and I’d guess that there’d be big differences in the tractability and neglectedness of increasing each sub-component.

For example, it seems like work to increase how empathetic and peace-loving people are is far less neglected than work to increase how much people care about the welfare of beings in the long-term future. For another example, I’d guess that it’s easier to (a) teach someone a bunch of specific facts that are useful for thinking about what the biggest existential risks are and where they should donate if they want to reduce existential risks, than to (b) make someone better at “critical thinking” in a general sense.

So perhaps one factor will be “on average” easier to increase than another factor, but there’ll be sub-components of the former factor that are harder to increase than sub-components of the latter factor.

But that’s how I’d think about this sort of question. Actually answering this sort of question would require more detailed and empirical work. I’m guessing a lot of that work hasn’t been done, and a lot of it has been done but hasn’t been compiled neatly or brought from academia into EA. I’d be excited to see people fill those gaps!

Apparently Owen Cotton-Barratt had also been developing what I see as a somewhat similar framework/set of ideas. He discusses it from around 1:01:00 to around 2:04:00 in an 80,000 Hours interview that was recorded in February 2020 but released in December.

I found that discussion of Owen’s framework interesting, and would recommend listening to the episode.

ETA: Owen has also recently published a series of relevant and interesting posts:

Everyday Longtermism

Blueprints (& lenses) for longtermist decision-making

Web of virtue thesis [research note]