FarmKind’s Illusory Offer

While the effective altruism movement has changed a lot over time, one of the parts that makes me most disappointed is the steady creep of donation matching. It’s not that donation matching is objectively very important, but the early EA movement’s principled rejection of a very effective fundraising strategy made it clear that we were committed to helping people understand the real impact of their donations. Over time, as people have specialized into different areas of EA, with community-building and epistemics being different people from fundraising, we’ve become less robust against the real-world incentives of “donation matching works”.

Personally, I would love to see a community-wide norm against EA organizations setting up donation matches. Yes, they bring in money, but at the cost of misleading donors about their impact and unwinding a lot of what we, as a community, are trying to build. [1] To the extent that we do have them, however, I think it’s important that donors understand how the matching works. And not just in the sense of having the information available on a page somewhere: if most people going through your regular flow are not going to understand roughly what the effect of their choices are, you’re misleading people.

Here’s an example of how I don’t think it should be done:

I come to you with an offer. I have a pot with $30 in it, which will go to my favorite charity unless we agree otherwise. If you’re willing to donate $75 to your favorite charity and $75 to mine, then I’m willing to split my $30 pot between the two charities.

How should you think about this offer? As presented, your options are:

Do nothing, and $30 goes from the pot to my favorite charity.

-

Take my offer, and:

$75 goes from your bank account to your favorite charity

$75 goes from your bank account to my favorite charity

$15 leaves the pot for your favorite charity

$15 leaves the pot for my favorite charity

While this looks nice and symmetrical, satisfying some heuristics for fairness, I think it’s clearer to (a) factor out the portion that happens regardless and (b) look at the net flows of money. Then if you take the offer:

$150 leaves your bank account

$90 goes to your favorite charity

$60 goes to my favorite charity

If I presented this offer and encouraged you to take it because of my “match”, that would be misleading. While at a technical level I may be transferring some of my pot to your favorite charity, it’s only happening after I’m assured that a larger amount will go to mine: you’re not actually influencing how I spend my pot in any real sense.

Which is why I’m quite disappointed that Charity Entrepreneurship decided to host a project that, after considering these arguments, decided to build FarmKind:

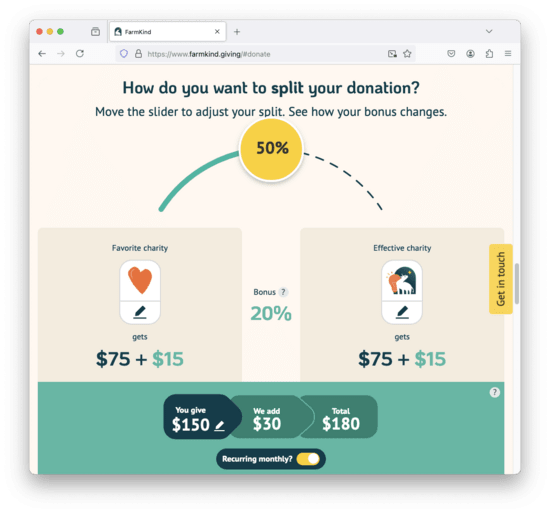

This is an animal-specific giving platform, largely inspired by GivingMultiplier. [2] It’s not exactly the same offer, in part because it has a more complex function for determining the size of the match, [3] but it continues to encourage people to give by presenting the illusion that the donor is influencing the matcher to help fund the donor’s favorite charity.

While setting up complex systems can cause people to donate more than they would otherwise, we should not be optimizing for short-term donations at the expense of donor agency.

Before starting this post I left most of these points as comments on the EA Forum announcement. I also shared a draft of this post with FarmKind and GivingMultiplier for review late Wednesday morning:

I’ve drafted a blog post that is critical of your work, and I wanted to share it with you before publishing it so that you’re not surprised by it: Farmkind’s Illusory Offer. I’m planning to publish this on Friday (August 7th [JK: this should have said 9th!]) morning, but if you’d like more time to prepare a response let me know and I can delay until Wednesday (August 14th).While GivingMultiplier responsed with a few small requested edits, FarmKind didn’t respond. At the time I thought this was because they had decided to stop engaging with me but actually it was because the email ended up in their spam folder. After publishing FarmKind let me know about this and pointed out a few places where I had misunderstood them. I appreciate the corrections and have edited the post.

[1] I think participating in existing donation match systems is

generally fine, and often a good idea. I’ve used employer donation

matching and donated via Facebook’s Giving Tuesday match, and at a

previous employer fundraised for GiveWell’s top charities through

their matching system. In the latter case, in my fundraising I

explicitly said that the match was illusory, that I and the other

sponsors would be donating regardless of what others did, and that

people should read this as an invitation to join us in supporting an

important effort.

[2] In 2021 I raised similar issues with GivingMultiplier, prompting them to add a transparency page. I appreciate GivingMultiplier’s public explanation, and that FarmKind is also pretty public about how their system works.

[3] GivingMultiplier’s algorithm for determining the bonus amount was “50% of the amount donated to effective charity”. Here it’s usually higher and occasionally lower (sheet):

Comment via: facebook, lesswrong, the EA Forum, mastodon

- FarmKind’s Illusory Offer by (9 Aug 2024 11:32 UTC; 113 points)

- FarmKind’s Illusory Offer by (LessWrong; 9 Aug 2024 11:30 UTC; 72 points)

- 's comment on FarmKind: Using a diet offset calculator to encourage effective giving for farmed animals by (11 Feb 2025 17:21 UTC; 37 points)

- 's comment on AI Safety Newsletter #41: The Next Generation of Compute Scale Plus, Ranking Models by Susceptibility to Jailbreaking, and Machine Ethics by (LessWrong; 11 Sep 2024 20:49 UTC; 13 points)

- 's comment on Thomas Kwa’s Quick takes by (29 Nov 2024 23:14 UTC; 7 points)

My reflections on 5 criticisms of FarmKind’s bonus system:

Hello!

After receiving impassioned criticisms on our announcement post last week, I decided to use a plane trip (I’ve been on leave) to reflect on them with a scout mindset to make sure Thom and I aren’t missing anything important that would mean we should change our approach. I’m glad I did, because on my way back from leave I noticed this new post. I thought it would help to share my reflections.

To set expectations: We won’t be able to continue engaging in the discussion on this here. This is not because we consider the “case closed”, but because we are a team of 2 running a brand new organization so we need to prioritise how we use our time. It’s important (and a good use of time) for us to make sure we consider criticisms and that we are confident we are doing the right thing.[1] But there is a limit to how much time we can dedicate to this particular discussion. Please enjoy the ongoing discussion, and apologies that we can’t prioritise further engagement with it :)

Before I get to my reflections, I want to point out an unhelpful equivocation I’ve seen in the discourse: Some of the comments speak of donation matching as if it’s one very specific thing, and they claim or imply that we are doing that one thing. In reality, “donation matching” can refer to a wide range of arrangements that can work in all sorts of ways.

The most common form of donation matching that I’ve seen involves a large individual or institutional donor promising to match all donations to a specific charity 1:1 until a certain date. This can be fully counterfactual (if the large donor chooses to participate in the match where they wouldn’t otherwise have given to that charity or any other) or it can be not counterfactual at all (if they would have given that amount to that charity no matter what), or somewhere in between. What we’re doing is different to this, as we explain here and below, which is why we don’t call it donation matching, as we aren’t wanting people to import expectations about how it works from previous experiences they may have had with common forms of donation matching.

It’s fair to have qualms with how some forms of donation matching work (or even all forms of it, as some commenters do). But most of the reasons given for concern about donation matching apply to some and not all forms of it. We would be able to make better sense of this collectively by being precise about what forms of donation matching we do and don’t have problems with and for what reasons.

Okay, on to my reflections on 5 criticisms of FarmKind’s bonus system:

Criticism 1: It’s not possible to donate $X in total and have >$X go to your Favorite Charity, which means we’re not offering a ‘meaningful match’ / we’re not delivering what we promise

We received this criticism: “The fact that you can’t donate $X and get more than $X going to your favourite charity means I don’t really feel like my donation is being meaningfully matched”.

We never promise or imply that it would be possible to donate $X in total and have >$X go to your Favorite Charity (after splitting and receiving a bonus). We make it very clear that it won’t:

Our comms make it very clear that FarmKind’s purpose is to help users donate to fix factory farming through our Super-effective Charities, with the ability to support your Favorite Charity at the same time and to get a bonus included as perks. It’s hard to see how anyone could read our comms and see things the way the critics are worried they will, and so it’s hard to see how anyone could be misled:

Criticism 2: Our comms suggest that your Favorite Charity receives money from the Bonus Fund, but that isn’t true

We received this criticism: “The ‘bonus’ is presented to users as if it (a) will go in part to their favorite charity and (b) is money that would not otherwise be going to help animals, but neither of these are true”[2]

We think this is incorrect, because it quite literally IS true that the Favorite Charity receives money from the Bonus Fund. This is how the money flows: Every.org splits the regular donors donation between their chosen Favorite and Super-Effective charity and then Every.org disburses money to each from the Bonus Fund in the exact way that’s summarised during the donation process:

Critics have pointed out that the effect of these cash flows is the same as a different set of cash flows where more of the donor’s money was given to their Favorite Charity than indicated (e.g. $90 of the $150 in the donation went to the Favorite Charity), and all of the bonus went to the Super-Effective Charity ($30 in this case). Those critics claim that this is a simpler set of cash flows, and a simpler/clearer way to understand what has happened. We disagree that it’s simpler or clearer, and even if it were, it wouldn’t be what actually happened, and it wouldn’t make our description misleading.

Criticism 3: Our comms are misleading regarding whether the bonuses we add to donations are counterfactual (criticism fleshed out below)

This is an interesting and nuanced one. The criticism goes something like:

The average donor assumes that in donation matching, the matching funding added to their donation would not have otherwise…

(a) been donated OR

(b) been donated to the same cause OR

(c) been donated to the same charities

Because we will not promise a bonus for a donation if the money isn’t already in the Bonus Fund, and if no donations were ever made that money would eventually go to the Impact Fund, our bonus system doesn’t work the way the average donor assumes it does, and we don’t make this clear enough, and so it’s misleading

There are valid aspects of this criticism, which I nonetheless disagree with, and there are invalid aspects. Let’s start with what the criticism gets right and wrong about the reality of the counterfactuality of the bonus system:

Counterfactuality of the bonus system

Regular donations do, in expectation, cause more counterfactual donations to occur. Let’s talk through it, considering counterfactuals in both the narrower/direct and the broader/indirect sense:

1. The narrower/direct sense — i.e. Thinking just about the money that’s already in the bonus fund when a regular donation is made:

(a) Total donations: At the moment that a regular donation is made, that donation doesn’t increase the total amount of money given to charity, because the funds in the Bonus Fund have already been given, and if no more donations ever occurred and FarmKind shut down, we would give the balance of the Bonus Fund to our Super-effective Charities (as explained at farmkind.giving/support-bonus-fund) ❌ no direct counterfactual impact on total donations ❌

(b) Causes: The regular donor gets to pick any Favorite Charity, from any cause, and their donation will cause money from the Bonus Fund to go to it. Unless by some miracle, the Bonus Fund supporters would otherwise have collectively donated to the same causes as the regular donors in the same proportions, then regular donations do have direct counterfactual impact on how much money goes to different causes ✅ direct counterfactual impact on donations to different causes ✅

(c) Charities: The regular donor gets to pick any Favorite Charity and one of our Super-effective Charities and their donation will cause money from the Bonus Fund to go to it. Unless by some miracle, the Bonus Fund supporters would otherwise have collectively donated to the same charities as the regular donors in the same proportions, then regular donations do have direct counterfactual impact on how much money goes to different charities (both ‘effective’ and ‘ineffective’) ✅ direct counterfactual impact on donations to different charities ✅

2. The broader/indirect sense — Regular donations on our platform, which receive a bonus, use up the supply of money that’s in the pool. The more regular donations that occur (i.e. the more demand there is to redeem our bonuses), the more that folks who like how our bonus system is motivation donations will want to keep the system going, by donating to the Bonus Fund. In particular, if the Bonus Fund is running low, we will communicate this to people who like our bonus system, imploring them to donate to keep the system going. As such, each regular donation increases, in expectation, the amount of money contributed to the Bonus Fund.

This is like the how buying one of chickens at the grocery store (which the grocer has already bought and so pre-committed to selling or throwing away) increases the expected amount of chicken they will buy next time. If you think that lower demand for animal products can decrease the amount of animal products produced, you should understand how increased demand for bonus funding can increase the amount of money given to the Bonus Fund.

But what would have happened to the money donated to the Bonus Fund were it not for past demand?

(a) Total donations: That’s what M&E is for, but in all likelihood, as with all fundraising efforts, some money raised would otherwise have gone to charity and some wouldn’t have ✅ indirect counterfactual impact on total donations ✅

(b) Causes: For the money that would have otherwise been given to charity, the odds are infinitesimal that it would have gone to the same causes and specific charities that the regular donors chose, in the same proportions ✅ indirect counterfactual impact on donations to different causes ✅

(c) Charities: See above^ ✅ indirect counterfactual impact on donations to different charities ✅

Do we communicate about it in a dishonest way?

Certainly not. Our communications are accurate, both in the ‘large print’ and the ‘fine print’.

Do we communicate about it in a misleading way?

It is possible to be misleading without being dishonest, however. This can be done by presenting information in a way that leads someone to draw incorrect conclusions, even though the facts themselves are technically true. Typical ways to do this is by omitting certain information, or framing the facts in a particular way.[3]

To cut right to the chase: Will some people who don’t read our communications carefully think that they’re having direct counterfactual impact on total donations, when they aren’t [as per (1)(a)]? Probably yes, there is always a risk that some people will get the wrong idea. However, we don’t believe that this constitutes misleading communication. Let me explain why:

We take reasonable steps to dispel misconceptions, making what we believe are appropriate and ethical trade-offs to ensure honest communication (although people could reasonably disagree):

Measures we take:

We don’t call what we do “matching”, in order to reduce the association with the most common form of matching campaigns (and common misconceptions that come with them)

In order to donate, users must click a box confirming that they agree with our terms of use and that they “understand that the bonus funds are already pre-paid by bonus fund supporters. Learn how our bonus system works here.”

If one clicks any of the various links to learn more about how the process works, they’ll be taken to farmkind.giving/support-bonus-fund, where we explain exactly how the system does and doesn’t allow regular and bonus fund donors to increase their counterfactual impact (I won’t quote the explanation here because it’s too long).

In the section about the Bonus Fund on our About Us page, we say: “We help you multiply your impact by boosting your donation with prepaid bonus funds… These funds have been contributed by other donors who want to motivate more people to donate to fix factory farming. When you get you a bonus added to your donation through our platform, you get to direct these funds to the Favorite charity and the recommended Super-effective charity of your choosing.”

The need for trade-offs in honest communication:

Honest communication involves trade-offs between two goals (among others): Having those who read it form maximally true beliefs — this is the ‘honest’ bit — and making your communication sufficiently simple, concise and interesting that people actually listen to /read it — without this, you haven’t actually done the ‘communication’ bit.

Everyone we’ve ever encountered makes these sorts of trade-offs, and considers them to be a part of honest communication. Of course, it’s also possible to make the trade-off wrong and fail to communicate or do so honestly. Here are various some examples, some of which you may think get the balance right and others of which you may not:

Every product/service’s terms and conditions and how they surface them to users (I think we’ve all seen examples we think are acceptable and others we think aren’t. Do any readers think that 100% of cases where one clicks to agree with terms and conditions without being forced to read them in detail are misleading?)

Teaching Newtonian Physics to early high-school students, even though it’s technically incorrect (I think this is acceptable, as it’s simple enough for students at this level to understand and is a helpful building block towards the correct model that uses Special Relativity)

I’ve put two more in the footnotes for brevity’s sake[4]

To sum this point up: People who read the donation form carefully as they fill it out (or who is otherwise curious and so clicks around to learn what this “bonus” thing is all about) will understand it and be making an informed donation decision. People who skim it, may misunderstand what’s happening and so not be fully informed. We’ve taken measures to reduce the likelihood of such misunderstandings, because we think it’s the right thing to do for deontological reasons. It would be possible to take more intense measures (like a series of pop-ups reminding donors several times that bonus funds are pre-committed), but given the trade-offs, we think it wouldn’t be right for consequentialist reasons. Different people will reasonably disagree on what measures we ought to take for deontological reasons, and there is no level that is immune from the criticism that they ought to do more.

Even if donors have a misconception about how participating in the bonus system increases their impact, they understand that it increases impact. As discussed, despite our efforts, a skim reading donor may believe that getting a bonus is counterfactually impactful in a way that it isn’t, but there are still 5 other ways (2 direct, 3 indirect) that it IS counterfactually impactful, causing more donations to go to the things they care about. This, after all, is the promise that makes receiving a bonus attractive.

Criticism 4: By encouraging both regular and bonus donors to participate in the bonus system to amplify their impact, we’re causing a double-counting of impact which is suboptimal for collective resource allocation

This is also an interesting one, which we’re grateful was raised, and we will incorporate this into future comms.

Such a double count is likely, and is one of the challenges with counting impact using standard counterfactual reasoning (see discussion here and here). These kinds of double-countings are actually really common. For example, whenever two advocacy groups both play a necessary role in achieving a policy change, they will generally both conclude that the counterfactual impact of their work is the full impact of the policy change. This double count of impact can lead to an inaccurate view of the cost-effectiveness of each group, leading to suboptimal grantmaking decisions.

What are we to do about this? Surely the answer isn’t to not encourage both groups to participate in our bonus system — after all, the participation of each group counterfactually causes higher impact. Each group benefits (in terms of increased impact. We don’t think the answer is to introduce Shapley Values or some other more complicated means of impact attribution, which would compromise our ability to communicate the value to each group. Rather, we should probably talk about the increased impact each group will have in general terms, without using specific numbers unless someone asks for them and/or we heavily caveat them. Having received this criticism, we would not use specific numbers the way we didhere again.

It’s worth mentioning that, of course, resource allocation is extremely far from perfectly efficient, so the real cost of these kinds of double counts is probably very low. It’s also worth reiterating that this problem applies to nearly every intervention in EA — it is not a particular problem of donation matching.

Criticism 5: FarmKind uses a form of donation matching, and even if fully understood and consented to by all parties, matching does not belong in EA because.. [various reasons]

It is reasonable to disagree about what is and is not ‘EA’. For example, we have similar disagreements with many EAs’ cause area prioritisation, epistemics, use of funding, communications styles. We also see many projects that don’t meet what we see as minimum standards in terms of the existence of feedback loops, theories of change, or measurement and evaluation.

We personally wouldn’t choose to claim there is no place for these people or projects in EA. We think that there is value in a more pluralistic and diverse EA community that takes many different approaches, all motivated by the honest desire to do the most good we can.

I’m sure it’s clear from our choice to launch this platform that we think this is a good thing to be doing, and that it’s our attempt at doing altruism effectively. If some folks who disagree decide that FarmKind does not belong in effective altruism, there is likely nothing we can say that will change their mind. That’s ok.

I don’t have more to say about this criticism except to reiterate that I respect its intention, I disagree and I thank people for sharing it. We considered Jeff’s critique post of Giving Multiplier prior to deciding to launch FarmKind and we were grateful to come across this perspective before rather than after making the decision — it influenced decisions we made for the better.

Thanks for reading, and happy foruming!

To that end, if any new points are made in response that we haven’t considered, we will consider them and may change our mind, but we may not neccessarily report back about this.

Criticism 2 is about part (a) of this statement. We discuss part (b) under Criticism 3

For example, stating “Our product has been used by over 1 million people!”, when 99% of people used it once, were dissatisfied and never used it again. The statement is true (and in that sense, not dishonest), but it omits context so that it might lead someone to believe that 1 million people are active, happy users, which isn’t the case.

3rd example: The donation platform Ribon using the half-sentence “Ensure free-range living for farm animals” to describe the impact of donating to a specific charity, even though no given donation can possibly guarantee this outcome is achieved (I think this is acceptable, and I’d hope that further comms were available for those who are interested enough to read more to understand how their donations might have an impact).

4th example: Saying “I like ice cream”, even if you think that the self is an illusion (an illusion which your statement reinforces), such that you’re giving the false impression that you think the self is a real thing (I include this example because I imagine that even our most steadfast critics would agree this is honest communication. The kind of person who caveats their use of the word ‘I’ is probably failing to communicate)

[not intending to take a substantive position on FarmKind here, probably using some information theory metaphors loosely]

Communication channels have bandwidth constraints. As a result, we have to accept that some loss of fidelity will occur when we try to convey a complicated set of information into a channel that lacks enough bandwidth to carry it without lossy compression. Example: Suppose I am a historian who is given 250 pages to write a history of the United States for non-US schoolchildren. Under most circumstances, the use of lossy compression to make the material fit into the available communication channel is fairly uncontroversial on its own. Someone who objects to the very idea—let’s call this a category-one objection—should perhaps be encouraged to read some of Claude Shannon’s basic works establishing the field of information theory.

But things will get a little more complicated when people see what specific material I omitted or simplified to make the material fit into 250 pages that schoolchildren can understand. Many disagreements would reflect a milder sort of criticism, say that I should have spent less space on the 18th century and more on the 20th. Let’s call that category two. Although these alleged errors in compression reflect substantive decisions on my part, there is no suggestion that they were meant to push any agenda on my part. Maybe I just like 18th century history, or have a purely academic difference of opinion with my critics. In general, the right response here is to acknowledge that differences of opinion happen, just like different reasonable data-compression approaches will reach somewhat different results. My critics are allowed to be unhappy about my choices, but they generally need to keep their criticisms at a low-to-moderate level.

However, some critics might levy heavier, category-three charges against me: that I made content choices and executed simplifications to push an agenda. For example, I could easily select and simplify material for my textbook with the goal of presenting the US as the greatest nation that has ever graced the face of the earth (or with the goal of presenting it as the source of most of the world’s ills). Or I might have done this without consciously realizing it. Here, the problem isn’t really about the need to compress rich data to fit into a narrow channel, and so appeals to channel constraints are not an effective defense. It is about the introduction of significant bias into the output.

And of course the lines are blurry between these three categories (especially the last two).

The hard part is placing various criticisms of FarmKind’s comms into a category. I think the long comment above implicitly places them into categories one and two. In that view, there is some simplification and omission going on, but the resulting message is fair and balanced in light of the communication channel’s constraints. I think some critics would place their criticisms in category three—that the selection and simplification of the material is slanted (intentionally or otherwise) in a way that isn’t close-to-inherent to lossy compression.

The only observation I’ll make on that point is to encourage people to imagine a FarmKind variant that promoted charities toward which one was indifferent (or on hard mode: charities they affirmatively detest). Would they find the material to be a fair summary of the mechanics and different ways to view them? Or would they find DogKind or BadPoliticianKind to be stacking the deck, including predominately positive information and characterizations while burying the less favorable stuff?

The money moved to their Favorite Charity isn’t positive counterfactually if their Favorite Charity gets less than the donor would have otherwise donated to their Favorite Charity on their own without FarmKind. I expect, more often than not, it will mean less to their Favorite Charity, so the counterfactual is actually negative for their Favorite Charity.

My guess for the (more direct) counterfactual effects of FarmKind on where money goes is:

Shift some money from Favorite Charities to EAA charities.

Separately increase funding for EAA charities by incentivizing further (EAA) donation overall. (Shift more money from donors to EAA charities.)

It is possible FarmKind will incentivize enough further overall donation from donors to get even more to their Favorite Charities than otherwise, but that’s not my best guess.

FWIW, I agree with point (c) Charities, and I think that’s a way this is counterfactual that’s positive from the perspective of donors: they get to decide to which EAA charities the bonus funding goes.

But something like DoubleUpDrive would be the clearest and simplest way to do this without potentially confusing or (unintentionally) misleading people about whether their Favourite Charity will get more than it would have otherwise. You’d cut everything about their Favorite Charities and donating to them, and just let them pick among a set of EAA charities to donate to and match those donations to whichever they choose.

I agree that anyone seeing how the system works could see that if they give $150 directly to their Favorite Charity, more will go to their Favorite Charity than if they gave that $150 through FarmKind and split it. But they might not realize it, because FarmKind also giving to their Favorite Charity confuses them.

An intuition pump might be: how would you feel if a FarmKind-style fundraiser (“OperaKind”) somehow got the donor list for your own favorite charity and sent out emails urging those donors to participate in OperaKind? Would you be excited, or more concerned that money might be shifted from your preferred charities to opera charities?

Or one could skip the hypothetical and just ask some of the big non-EA charities—if they think FarmKind would be counterfactually positive for them, they should be willing to turn over their donor lists for free which would be a major coup.

Disclaimer: I am mostly skimming as there’s a lot to read and haven’t gotten through it all. But I do believe part of the idea with FarmKind is that the donors are already sympathetic to animal charities, and agree with the premise of effective animal charities, but also just want to get some warm fuzzies in as well. As opposed to most of their money going to something they do not agree with or have any care for.

Or, you could add in large print that they would get more to their Favorite Charity if they just donated the same amount to it directly, not through FarmKind. That should totally dispel any misconception otherwise, if they actually read, understand and believe it.

@Jeff Kaufman Would you like to respond to this? Do you feel like this addresses your concerns sufficiently? Any updates in either direction?

I just skimmed it due to time constraints, but from what I read and from the reactions this looks like a very thoughtful response, and at least a short reply seems appropriate.

I didn’t respond because of the “we won’t be able to continue engaging in the discussion on this here”. FarmKind can decide that they don’t want to prioritize this kind of community interaction, but it does make me a lot less interested in figuring out where we disagree and why.

I think I’m broadly sympathetic to arguments against EA orgs doing matching, especially for fundraising within EA spaces. But there are some other circumstances I’ve encountered that these critiques never capture well, and I don’t personally feel very negative when I see organizations doing matching due to them.

There is at least one EA sympathetic major animal welfare donor who historically has preferred most their gifts to be only via matching campaigns. While I think they would likely donate these funds anyway, donating to matches run by them (which I believe are a large percentage of matches you see run by animal orgs) would cause counterfactual donations to that specific animal charity. So at least some percentage of matches you see in EA causes funding to move from a less preferred charity to a more preferred one for the matched donors. This matching donor also gives to many projects EAs might view as less effective, so giving to these matches is frequently similarly good to getting matched by Facebook on EA Giving Tuesday.

I think a much larger portion of donation matching than people in EA seem to believe is more like EA Giving Tuesday on Facebook than completely illusory — the funds would go to charity otherwise, but probably somewhat less effective charity. This probably isn’t the majority of donation matches, but I’ve frequently seen donors make their matching gifts somewhat genuinely. I’ve worked at probably 3-4 nonprofits that have run donation matching campaigns, including outside of EA. Only once have I seen a match where the charity expected to get the full amount independent of if the match was met by other donors. Of course, the counterfactual here is how good other donation opportunities for the donor might be, but for an EA organization working with a donor who frequently gives to less effective causes, the situation could be very similar to EA Giving Tuesday matches from Facebook.

I’ve frequently seen matching campaigns as a way to pitch the matcher on making a larger gift, not the other way around. This obviously isn’t transparent / explicitly said, but many normie charities explicitly will go “do a matching campaign!” to a potential major donor, to get them more interested/increase the amount they’ll give. Insofar as people believe the match is real, the net effect of this is the matching donor giving more than they would otherwise to that specific charity, and the matched donors also having some level of real counterfactual match.

For matches, it seems like sometimes, it just straightforwardly would increase the amount the matcher donates (because they are excited about the match, etc). So while the match might not be a true 1:1 match, it probably does counterfactually increase the funding going to the group and charity overall, even if the floor for the increase is 0.

There is a comment on LessWrong that suggests that matching is good for tax reasons for nonprofits. I don’t think this comment is correct on the facts or reason for matches, but donor diversity does help nonprofits pass the public support test, which reduces administrative costs, and matches probably do help organizations achieve this by increasing donor diversity.

I also think I generally feel bad vibes about this kind of post. I don’t know how to reconcile this with the EA I want to see, but if I imagine starting a new potentially cool project aimed at making the EA ecosystem more funding diverse, and immediately get a prominent person making a really big public critique of it, it would make me feel pretty horrible/bad about being on the forum / pursuing this kind of project within EA. That being said, I don’t think projects are above criticism, or that EA should back off having this kind of lens. But it just makes me feel a bit sad overall, and I agree with another commenter that donation matching debates often feel like isolated demands for rigour and are blown way out of proportion, without the potential benefits (more money for effective charity) being considered.

Maybe I feel something like this kind of critique is great, and debates about matching are great, but this as a top-level post seems a lot more intense than comments on the FarmKind announcement post, and the latter seems like the right level of attention for the importance of the criticism?

Moreover, through whose eyes do we assess this?

Suppose Open Phil decides to match $1MM in new-donor, small/medium donations to effective animal-welfare charities. It announces that any unused portion of the match will go to an AI safety organization. For example, it might think the AI safety org is marginally more effective but would prefer $1MM to the effective animal charities plus influencing $1MM that would otherwise go to dog/cat shelters. That does not strike me as manipulative or uncooperative; it would be an honest reflection of Open Phil’s values and judgment.

If Joe EA views both the animal charities and the AI safety org as roughly equal in desirability, the match may not be counterfactual. But through the eyes of Tom Animal Lover (likely along with the vast majority of the US population), this would be almost completely counterfactual. Tom values animal welfare strongly enough (and/or is indifferent enough to AI) that the magnitude of difference between the animal charity and the AI charity dwarfs the magnitude of difference between the AI charity and setting the money on fire.

All that is to say that if our focus is on respecting donors, I submit that we should avoid rejecting good matching opportunities merely because they are not counterfactual based on our own judgment about the relative merits of the charities involved. Doing so would go beyond affording donors respect and honesty and into the realm of infantilizing them.

I do think there are ways of doing donation matching that are more real than others, but at least in the case of EA organizations I would like to see the organization be public about this so donors can make informed tradeoffs. If I think $1 going to X is 70% as valuable as $1 going to Y, but X advertises 100% matching campaign, the details of the campaign matter if I’m going to make an informed decision on giving my dollar to X vs Y. For example, the organization could say what would happen with the money if it was not matched and whether past matches had been fully depleted.

In the case of FarmKind they are public about the details, which is great and I’m glad they do. Except that because all the money in the bonus fund is going to go to effective charities regardless of whether others donate, I think the first two considerations you give (match funders who also support less effective charities; matches sometimes don’t run out) don’t apply here.

I’m not happy about bringing this to a top-level post, but I also don’t really see other good options. I had previously raised issues with this general approach as misleading donors and the creators of FarmKind were aware of these arguments and decided to continue anyway. When Ben and I raised some of these issues in the comments on their announcement, my understanding was that FarmKind was not considering making any changes in response to our objections and considered the matter closed (ex: “That’s all the time I have to spend on this topic.”).

I’m confused why you’d say this—I mention this several times in my post as a reason for donation matching?

Yeah, I agree I was ambiguous here — I mean that it might be useful to see the tradeoffs more directly — e.g. the scale of the costs anti-matching people see against the theoretical upside of running matches (especially if the effects are potentially not major, as David Reinstein suggests). I think I see matching campaigns as much more like marketing than dishonesty though, and if I felt like they were more like dishonesty I might be more against them.

One thing I’ve thought about since writing my original comment: I think plausibly the degree to which one should think matching is bad ought to be somewhat tied to what the organization is doing. E.g. The Humane League or GiveWell aren’t trying to promote effective giving generally (maybe GiveWell a bit more) — they’re trying to move funds to specific impactful things, and so I maybe think our tolerance for hyperbolic marketing ought to potentially be a bit higher. I could see the case for an organization that was dedicated to effective giving specifically (e.g. Giving What We Can?) not doing matching due to the issues you outline as being stronger, since one of their goals is helping donors think critically about charitable giving. Maybe GiveWell is more ambiguously between those two poles though. Similarly, is FarmKind’s goal to move money to theoretically impactful animal groups, or to promote effective giving? Not really sure, but I’d guess more the former.

A question I genuinely don’t know the answer to, for the anti-donation-match people: why wasn’t any of this criticism directed at Open Phil or EA funds when they did a large donation match?

I have mixed feelings on donation matching. But I feel strongly that it is not tenable to have a general community norm against something your most influential actors are doing without pushback, and checking the comments on the linked post I’m not seeing that pushback.

Relatedly, I didn’t like the assertion that the increased number of matches comes from the ‘fundraising’ people not the ‘community-building and epistemics’ people. I really don’t know who the latter refers to if not Open Phil / EAF.

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/zt6MsCCDStm74HFwo/ea-funds-organisational-update-open-philanthropy-matching

I wasn’t an enormous fan of the LTFF/OP matching campaign, but I felt it was actually a reasonable mechanism for the exact kind of dynamic that was going on between the LTFF and Open Phil.

The key component that for me was at stake in the relationship between the LTFF and OP was to reduce Open Phil influence on the LTFF. Thinking through the game theory of donations that are made on the basis of future impact and how that affects power dynamics is very messy, and going into all my thoughts on the LTFF/OP relationship here would be far too much, but within that context, a very rough summary of the LTFF/OP relationship could be described as such:

The LTFF would have liked money from OP that was not conditional on the LTFF making specific grants that OP wanted to make (because the LTFF doesn’t want to be used for reputation-washing of Open Phil donations, and also wants to have intellectual independence in how it thinks about grants and wants to be able to make grants that OP thinks are bad). Previously the way the LTFF received Open Phil funding was often dependent on them giving us money for specific grants or specific classes of grants they thought were exciting, but that involved a very tight integration of the LTFF and OP that I think was overall harmful, especially in the post-FTX low-diversity funding landscape.

OP was pretty into this and also wanted the LTFF to become more independent, but my sense is also didn’t really want to just trust the LTFF with a giant pot of unconditional money. And given the LTFFs preferred independence from OP and OPs preferred distancing from the LTFF, OP really wanted the LTFF to put more effort into its own fundraising.

So the arrangement that ultimately happened is that OP agreed to fund us, if enough other people thought we were worth funding, and if it seemed like the LTFF would be capable of being an ongoing concern with its current infrastructure and effort put into it, even without OP funding. This was achieved by doing a matching thing. This isn’t the ideal mechanism for this, but it is a mechanism that lots of people understand and is easy to communicate to others, and was a good enough fit.

Matching was a decent fit because:

It forces the LTFF to put effort into fundraising and as such prevents the LTFF from (in some sense) holding the LTFF applications hostage by asking for more money from OP to fund them after the money was spent, without putting effort into fundraising until then

It forces the rest of the ecosystem to contribute their “fair share” of the LTFF contributions, by agreeing on a relative funding split in advance (whereas otherwise you might have donor-chicken problems where donors don’t want to give to the LTFF because they expect it would just funge 1-1 with OP donations)

I think in-general, matching campaigns for fair-split reasons are pretty reasonable. There are definitely many projects where I am happy to contribute 10% of their funding, if others filled the remaining 90%, but that I would not like to fund if I had no assurance from others that they would do so.

A lot of this stuff can also be solved with kickstarter-like mechanisms, though my guess is an LTFF kickstarter would have been worse, or would have needed to include a bunch of distinct funding levels in ways that would have made it more complicated.

In as much as people donated to the LTFF because they saw it as a substantial multiplier on their giving, I think that was sad and should have been fixed in communications. I think the right relationship was to see the multiplier that OP made as basically a determination from them on what their fair share for that year of LTFF funding was, and then to decide whether an LTFF funded at that ratio of OP to non-OP funding was reasonable, and if they thought it was unreasonable to consider that as a reason to not donate (or to get annoyed at OP in some other way for committing to an unfair funding split).

All that said, this is just my personal perspective on the matching campaign. I was quite busy during that time and wasn’t super involved with fundraising, and other people on the LTFF might have a very different story of what happened.

I made a reasonably large donation to LTFF at the time of the match, and it felt very clear to me exactly what the situation was, that the matching funds were questionably counterfactual, and felt like just a small bonus to me. I thought the comms there were good.

As Michael says, there was discussion of it, but it was in a different thread and I did push back in one small place against what I saw as misleading phrasing by an EA fund manager. I don’t fully remember what I was thinking at the time, so anything else I say here is a bit speculative.

Overall, I would have preferred that OP + EA Funds had instead done a fixed-size exit grant. This would have required much less donor reasoning about how to balance OP having more funding available for other priorities vs these two EA funds having more to work with. How I feel about this situation (on which people can choose to put whatever weight they wish—just illustrating how I think about this) does depend a lot on who was driving the donation matching decision:

If the EA Funds managers proposed it, I would prefer they hadn’t.

If OP proposed it, I would prefer EA Funds had tried to convince them to give a fixed-size grant instead. If they did and OP was firm in wanting to do a matching approach, then I think it was on balance ok for EA Funds to accept as long as they communicated the situation well. And EA Funds was pretty transparent about key questions like how much money was left and whether they thought they would hit the total. I think their advice EA Funds gave on what would happen to the money otherwise wasn’t so good but I’m pretty sure I didn’t see it at the time (because I don’t remember it and apparently didn’t vote on it). The guidance OP gave, however, was quite clear.

One thing that would have made pushing back at the time tricky is not knowing who was driving the decision to do the match.

But I also think this donation matching situation is significantly less of an issue than ones aimed at the general public, like GiveWell’s, GivingMultiplier’s, and FarmKind’s. The EA community is relatively sophisticated about these issues, and looking back I see people asking the right questions and discussing them well, collaborating on trying to figure out what the actual impact was. I think a majority of people whose behavior changed here would still endorse their behavior change if they fully understood how it moved money between organizations. Whereas I think the general public is much more likely to take match claims at face value and assume they’re literally having a larger impact by the stated amount, and would not endorse their behavior change if they fully understood the effect.

FWIW, I had started a thread on the EA Funds fundraising post here about Open Phil’s counterfactuals, because there was no discussion of it.

I’m not in the anti-donation-match camp, though.

Also, Jeff hinted at the issue there, too, and seemed to have gotten downvotes, although still net positive karma (3 karma with 8 votes, at the time of writing this comment).

I hear this as “you can’t complain about FarmKind, because you didn’t complain about OpenPhil”. But:

Jeff didn’t complain about the GiveWell match at the time it was offered, because he didn’t notice it. I don’t think we can draw too much adverse inference from any specific person not commenting on any specific situation.

A big part of my motivation to leave a comment on the FarmKind post was anticipating that they might not have heard about common objections to donation matching, whereas I think Claire Zabel probably has heard of them.

Similarly, one might have differing expectations about how much one vs. the other organisation would be interested in your feedback, or likely to change path based on feedback (I don’t really have a considered view on how FarmKind vs. OpenPhil score here)

idk, sometimes I feel like leaving comments and sometimes I don’t?

I think it’s better to focus on the actual question of whether matches are good or bad, or what the essential features are for a match to be honest or not. Based on that question, we can decide “it was a mistake not to push back more on OpenPhil” or “what OpenPhil did was fine” if we think that’s still worth adjudicating.

I’m sorry you hear it that way, but that’s not what it says; I’m making an empirical claim about how norms work / don’t work. If you think the situation I describe is tenable, feel free to disagree.

But if we agree it is not tenable, then we need a (much?) narrower community norm than ‘no donation matching’, such as ‘no donation matching without communication around counterfactuals’, or Open Phil / EAF needs to take significantly more flak than I think they did.

I hoped pointing that out might help focus minds, since the discussion so far had focused on the weak players not the powerful ones.

While I think a norm of “no donation matching” is where we should be, I think the best we’re likely to get is “no donation matching without donors understanding the counterfactual impact”. So while I’ve tried to argue for the former I’ve limited my criticism of campaigns to ones that don’t meet the latter.

If you’re just saying “this other case might inform whether and when we think donation matches are OK”, then sure, that seems reasonable, although I’m really more interested in people saying something like “this other case is not bad, so we should draw the distinction in this way” or “this other case is also bad, so we should make sure to include that too”, rather than just “this other case exists”.

If you’re saying “we have to be consistent, going forward, with how we treated OpenPhil / EA Funds in the past”, then surely no: at a minimum we also have the option of deciding it was a mistake to let them off so lightly, and then we can think about whether we need to do anything now to redress that omission. Maybe now is the time we start having the norm, having accepted we didn’t have it before?

FWIW having read the post a couple of times I mostly don’t understand why using a match seemed helpful to them. I think how bad it was depends partly on how EA Funds communicated to donors about the match: if they said “this match will multiply your impact!” uncritically then I think that’s misleading and bad, if they said “OpenPhil decided to structure our offramp funding in this particular way in order to push us to fundraise more, mostly you should not worry about it when donating”, that seems fine, I guess. I looked through my e-mails (though not very exhaustively) but didn’t find communications from them that explicitly mentioned the match, so idk.

In support of this view: There was a lot going on with the Open Phil EAIF/LTFF funding drawdown & short-term match announcement. Those funds losing a lot of their funding was of significant import to the relevant ecosystems, and likely of personal import to some commenters who expected to seek EAIF/LTFF funding in the future. The short-term matching program was only a part of the larger news story (as it were). So commenter attention on that post was fragmented in a way that was not the case with FarmKind’s post.

In non-support of this view: Given AIM’s involvement with FarmKind’s launch, I would be really surprised if its founders were unaware of the critiques that had been levied against donation-matching programs over the past 10-15 years in EA. It is also unclear how much FarmKind could change course based on feedback (other than giving up and shutting down); matching is core to what it does in a way that isn’t true of Open Phil.

Other than giving up and shutting down, they could have put offsetting front and center. I think it might be psychologically compelling to some who don’t want to give up meat to be able to undo some of their contributions to the factory farming system. I actually became aware of their calculator from your quick take, as currently it is pretty hard to find.

An interesting idea! I think an offset-based strategy has some challenges, but I’d be interested in seeing how it went. It tries to sell a different affective good than most traditional efforts (guilt reduction, rather than warm fuzzies), and a fundraising org probably has to choose between the two.

On the plus side, it probably appeals to a different set of donors. On the down side, you’d find it hard to collect more than the full-offset amount from any donor.

(Working out the ethics of quilting one’s prospective donors is too complex for a comment written on commuter rail....)

Someone could not just eliminate their contribution to FF but be part of the solution if their contribution is a greater than one multiple of the offset. I think people might like a 1.5 to 2X offset potentially for the warm fuzzies.

There are lots of options helping animals (through raising money or otherwise) that don’t involve this kind of competition around the impact of donations. It’s common for startups to pivot if their first product doesn’t work out.

I think FarmKind would be constrained by the need to keep faith with its donors, though. I agree about pivoting when there has been a material change in facts or circumstances. That’s an understood part of the deal when you donate to a charity. But I don’t see any evidence of the product on which FarmKind raised its seed funding was not “work[ing] out” in practice. It had just launched its platform. The critiques you and Ben offered were not novel or previously unknown to FarmKind (e.g., their launch info cites Giving Multiplier as a sort of inspiration).

It is of course good to change your mind when you realize that you made an error. But from the seed donor perspective, changing paradigms so early would look an awful lot like a bait and switch in effect if not in intent. If an organization fundraises based on X and then promptly decides to do something significantly different for reasons within the organization’s control without giving X a serious try, I think it should generally offer people who donated for X idea to have their donations regranted elsewhere. Whether its donors would chose that is unknown to me.

Independently, it’s not clear that a pivot would be practically feasible for FarmKind (or most other CE incubatees a few months after launch). It launched on a $133K seed grant with two staff members about three months ago (not including time spent in the CE program). Even assuming they could get 100% donor consent for repurposing funds, they would still be going almost back to square one. It’s not clear to me that it could come up with a new idea, spend the time to develop that, relaunch, and show results to get funding for the rest of year 1 and beyond (which has been a big challenge for many CE-incubated orgs).

Given those constraints, I think it is fair to say that the extent to which FarmKind could realistically change course in response to criticism (other than winding down) remains unclear.

Yeah, in retrospect maybe it was kind of doomed to expect that I might influence FarmKind’s behaviour directly, and maybe the best I could hope for is influencing the audience to prefer other methods of promoting effective giving.

That’s a good question, and certainly the identity of the matching donor may have played a role in the absence of criticism. However, I do find some differences there that are fairly material to me.

Given that the target for the EA Funds match was EAs, potential donors were presumably on notice that the money in the match pool was pre-committed to charity and would likely be spent on similar types of endeavors if not deployed in the match. Therefore, there’s little reason to think donors would have believed that their participation would have changed the aggregate amounts going toward the long-term future / EA infrastructure. That’s unclear with FarmKind and most classical matches.

Based on this, standard donors would have understood that the sweetener they were offered was a degree of influence over Open Phil’s allocation decisions. That sweetener is also present in the FarmKind offer. It is often not present in classical matching situations, where we assume that the bonus donor would have probably given the same amount to the same charity anyway.

The OP match offer feels less . . . contrived? OP had pre-committed to at least sharply reducing the amount it was giving to LTFF/EAIF, and explained those reasons legibly enough to establish that it would not be making up the difference anyway. It seems clear to me that OP’s sharp reduction in LTFF/EAIF funding was not motivated by a desire to influence third-party spending though then offering a one-time matching mechanism.

Even OP’s decision to offer donor matching has a potential justification other than a desire to influence third-party donations. Specifically, OP (like other big funders) is known to not want to fund too much of an organization, and that desire would be especially strong where OP was planning to cut funding in the near future. If OP’s main goal were to influence other donors, they frankly could have done a lot better job than advertising to the community of people who were already giving to LTFF/EAIF, matching at 2:1, not requiring that the match-eligible funding be from a new/increased donor, etc.[1] In contrast, FarmKind’s expressed purpose (and predominant reason for existence) is to influence third-party donations toward more effective charities.

Another possibly relevant difference is that the OP matching offer was time-limited and atypical, while FarmKind’s offer is perpetual. I’m not sure why this is intuitively of some relevance to me. Is it that I’m more willing to defer to the judgment of an organization that rarely matches, that this particular scenario warrants it? Is it that I think time-limited and atypical match offers are more likely to be counterfactual? Or is this a reaction to me finding a perpetual match to be gimmicky?

Finally, I sense that OP and the expected standard donors in the LTFF/EAIF match are significantly more aligned than FarmKind and its expected standard donors. Apparently any 501(c)(3) can be a donor-selected “favorite” charity there. Even if we think the median FarmKind donor is picking something like a cat/dog shelter, there’s still much less alignment between the donors’ expressed favorite and FarmKind’s objectives in offering the match.

So the OP situation seems directionally closer to a group of funders who are already on the same page trying to cooperate on a joint project, while the FarmKind situation seems more like an effort to divert money from standard donors who aren’t already aligned. Perhaps the clearest indicator here is FarmKind’s request, on the Forum and on its website, that people who were already on board with farmed-animal welfare not made standard donations! So I would expect OP to have acted in closer alignment to its expected standard donors’ interests than FarnKind, merely because it was already aligned with them.

The structure was also quite open to donors merely accelerating donations they were going to make to LTFF/EAIF anyway. And I expect EAs were quite likely to pick up on this.

Do you have a sense of why this issue is at the top for you?

To me it feels like an isolated demand for rigour. When I compare this to other norms like being unclear what cause area you support, not having external reviews (for e.g. meta and x-risk orgs) or many orgs not even having a public budget (making cost effectiveness comparisons near impossible), this issue seems pretty far down the list of community norms that EAs prescribe but do a week job at doing in practice.

That’s a good question! As I said in the post, this is not my top issue in any objective sense, only what makes me most disappointed. That is, this is a place where the community had come to (what I consider) the right answer, but then backslid in response to external incentives.

I’m confused about what you mean by not being clear which cause area you support? Do you mean individuals not making their donations public? Or not disclosing how they personally prioritize cause areas?

On the question of whether organizations should have external reviews and public budgets, to me this comes down to whether organizations are raising funds from the general public. The general principle is that donors should have the information they need to make informed decisions, and if an organization is raising funds from a small group, it is sufficient to be transparent to that group, which generally has much lower costs than being transparent to the world as a whole. (I also don’t see this as a place where the EA community in general has started failing at something it used to be good at)

I haven’t encountered any donors complaining that they were misled by donation matching offers, and I’m not aware of any evidence that offering donation matching has worse impacts than not having it, either in terms of total dollars donated or in attempts to increase donations to effective charities.

However, I haven’t been actively looking for that evidence—is there something that I’ve missed?

When I was at Google, I participated in an annual donation matching event. Each year, around giving Tuesday, groups of employees would get together to offer matching funds. I was conflicted on this but decided to participate while telling anyone who would listen that my match was a donor illusion. Several people were quite unhappy about this, where they told me that it was fraud for me to be claiming to match donations when my money was going to the same charity regardless of their actions. They were certainly not mollified when I told them that this was very common.

I think the main reasons you don’t see complaints about this from the general public is (a) most of the time people do not realize that they are being misled (b) people are used to all kinds of claims from charities that do not pass the smell test (“$43 can save a life!”) and do not expect complaining to make anything better.

One thing I’d like to add is that when there’s pushback on donation matching initiatives, the discussion often focuses on “is the communication of what happens clear?” and “are donors misled?” and so on. I think (lack of) honesty and clarity is the biggest problem with most donor matches, but even where those problems are resolved, I think there are still other problems (e.g. it just seems kind of uncooperative / adversarial to refuse to do something good that you’re willing and able to do unless someone else does what you want). My favoured outcome is not “honest matching” but “no matching”, and I’d like the discussion to at least have that on the table as a possible conclusion.

(To be clear, I think neither Giving Multiplier nor FarmKind are intending to be dishonest, although I think it’s still unclear to me whether they are unintentionally misleading people. I perhaps think that they are applying ordinary standards of truthfulness and care, whereas I’d like us to have extraordinary standards.)

If providing funds that will contribute to a match has the effect of increasing funds generated to effective charities and is transparent and forthright about the process involved, I don’t really see the problem.

It does not seem to me as an uncooperative and adversarial process, but one that gets more people involved in effective giving in a collaborative and fun experience. As the OP suggested, there is a concern that the matcher (as opposed to the fund provider) may be deceived and not realize that the net effect of their participation is less funds to their preferred charity and more to the fund provider’s preferred charity. But if there is adequate understanding of the process, it seems to me that the question boils down to whether or not the availability of Giving Multiplier or Farmkind results in more counterfactual donations going to these charities.

I think this is a pretty interesting aspect of the discussion, and I can see why people would not only agree with this but think it kind of obvious. Here are some reasons why I don’t think it’s so obvious:

I think it’s worth noticing when you offer other people something that you wouldn’t take yourself. Why is it good for them, but not good for you?

I think you should include your assessment of what value the deal has to someone else in your assessment of whether you have successfully communicated what the deal is. As above, if people are taking an offer that you wouldn’t take, and that as far as you see doesn’t benefit them, I think you should take that as evidence that you haven’t explained the deal (Jason makes this point in another comment)

I think a useful analogy is a casino, say a roulette wheel. The rules of roulette wheels are pretty simple, and completely public. People play them willingly, often believing it’s in their interests to do so. Yet I think roulette wheels are kind of exploitative and even verge on predatory, and I wouldn’t feel comfortable running one even to donate the proceeds to charity. Again, opinions can differ here, but for me I see facilitating and encouraging other people to make decisions that you know are bad isn’t ethical behaviour, even if they ultimately make the decision freely and willingly. (To be clear, I think offering a donation match is less unethical than running a casino, but I bring up the casino to illustrate how offering people a free and informed choice sometimes still doesn’t sit right with me.)

I think your example of the roulette wheel is illustrative… People know that they are going to lose money in expectation but it is rational for many of them to play because the expected fun they have from a night at the casino exceeds the expected loss. For example if you churn $500 and the average payback is 92.5%, the expected loss is $33.50 and you might have more fun than with other recreational activities that cost that much. Of course, some people may have gambling problems or may irrationally think that they have an advantage. These are the cases that we should be worried about: people who have issues of understanding or volitional capacity.

Similarly, people can understand what’s going on with Farmkind or Giving Multiplier and want to participate, understanding that their choice is benefiting the charities that Farmkind or Giving Multiplier prefer.

If they enjoy and understand the process employed, I don’t understand why one would think that they were harmed or exploited

On the casino example: I agree that a gambler could decide that the expected financial loss was outweighed by the value they ascribed to the entertainment. However, that doesn’t tell us what proportion of people around the roulette wheel fall into that category vs. people with impulse-control disorders or the like vs. people who do not have disorders yet make harmful decisions because they are too influenced by gambler’s fallacies. I would put the burden on the would-be casino operator to prove that enough[1] of their would-be customers fell into the “rational gambler” category before considering Ben’s objection to running a roulette wheel have been satisfactorily addressed.

Turning to the analogy, I think there is considerably more evidence of the “rational gambler” category existing than the “people who truly understand an FarmKind-type match, but enjoy it enough to experience it as a net positive.” A full understanding of the financial realities of gambling doesn’t seem logically inconsistent with deriving enjoyment from it—people like winning even when a win has absolutely zero practical import, and people like dopamine hits. Nor does a full understanding seem inconsistent with valuing that enjoyment at $33.50, which is comparable to what they pay for nights of entertainment they report as having roughly equivalent value.

In contrast, I’m having a hard time characterizing a plausible mechanism of action for the FarmKind scenario that produces some valued internal state (cf. “entertained” in the casino example) without either conflicting with other evidence about the standard donor’s preferences (which charity is their favorite) or being inconsistent with the standard donor having a true understanding of the match (that the only real-world difference from the world in which they directly donated to their preferred charity is more money going to the super-effective charity, with an equal reduction of the amount going to their preferred charity).

Pondering what “enough” means opens up a new can of worms for sure.

While I understand the concern that people might only participate in FarmKind’s matching because they misunderstand it, I believe there are those who could find psychological or strategic value in the process even with full understanding. My main point was that, if participants are fully informed and still choose to engage, then any ethical issues are primarily about ensuring transparency. I disagree with the idea that there’s something inherently wrong with the process itself, as long as there’s no deception involved.

I suppose you are saying that this is a situation where the facts are such that there should be a presumption of the participant being misled. But, arguendo, if the participant fully understands the process and chooses to engage, is there some residual wrongfulness? Because I would think the remainder of the inquiry is a prudential question of whether it has the effect of raising more funds for the effective charities.

[note that this is not about FarmKind specifically. It’s a response on whether encouraging the donor to take a deal that is clearly inconsistent with their professed interests is OK as long as the donor fully understands the arrangement]

I think there is a strong—but not irrebuttable—presumption that the person fails to fully understand the process. Based on the differences in opinion, even the Forum readership seems to not be having an easy go at that . . . and that’s a group of intelligent people whose background should make it a lot easier! I also suspect that relatively few people would go through with it once they had a full understanding. The basis for that suspicion is that it doesn’t make sense with the user’s professed preferences, and the mechanism by which the user would gain enough psychological or strategic value have not been clearly defined. It might be possible to address those concerns, but likely at the cost of making the fundraising pitch less effective than other approaches.

I’d only be willing to tolerate a low number of donors who were not fully informed slipping through the cracks. Part of it is that the org is actively creating the risk for donors to be misled. From a Bayesian point of view, a low base rate for full understanding in the pool of people who tentatively plan to donate would mean that the process for testing whether the person has full understanding needs to have an an awfully low false-positive rate to meet my standard.[1] So the charity would need a robust process for confirming that the would-be donor was fully informed. Maybe they could ask Jeff and Ben to do a video on why the process was illusory and/or misleading in their opinion? After all, it’s hard to be fully informed without hearing from both sides.

After all of that, I question whether you are going to have enough donors completing to make the matching fundraiser more effective than one with a more straightforward pitch. Obviously, one’s results may differ based on the starting assumption of how many potential donors would go ahead with it if fully informed.

Finally, I question whether this approach plays the long game very well. By the end of the understanding-testing process, the hypothetical donor would know that the modus operandi of the matching org is to ask people to engage in illusory matches that the organization knows are inconsistent with advancing said person’s stated preferences. That does not sound like a good strategy for building long-term relationships with donors . . . and long-term relationships are where a lot of the big money comes in.

Suppose only 5% of candidates have the required full understanding and should pass. If the process for confirming full understanding is even 90 percent accurate, I think we’d expect 4.5 correct pass results, 0.5 false fail results, 81 correct fails, and 9 false passes per 100 examinees. In other words, a full 2⁄3 of the passes wouldn’t have the needed full understanding.

I think I may have hidden the question that I was interested in my response.

I understand with your understanding of the motives and interests of the relevant actors, it is unlikely (maybe impossible?) for someone to do the matching process while understanding it fully.

But if that premise is satisfied, for the sake of argument, does that resolve the ethical question for you? Because my main issue was that Ben was suggesting that it would not.

Assuming the fundraiser, object-level charity, and those in privity with them had always acted in an ethically responsible manner with respect to the donor, I think the confirmed-full-understanding premise could resolve the ethical problem.

(I’m hedging a bit because I find the question to be fairly abstract in the absence of a better-developed scenario. Also, I added the “always acted” caveat to clarify that an actor at least generally cannot behave in a manipulative fashion and then remove the resultant ethical taint through the cleansing fire of confirmed-full-understanding. I’m thinking of scenarios like sexual harassment of employees and students, or brainwashing your kids.)

If the match is completely illusory, such that no well-informed donor would rationally give it any weight, I would start with a fairly strong presumption that the people donating lack an “adequate understanding of the process.” I don’t think that presumption is irrebuttable, but I would probably be looking for something like a pop-up that said something like:

We want you to understand that the “match” here is an illusion. Choosing to donate through this site does not result in more money going to animal charities than donating the same amount directly to your favorite charity would. The only meaningful real-world difference between donating through this site and donating the same amount to your favorite charity is that the effective charity receives more money (and your favorite charity receives less) when you donate through this site. Please initial in the box below to document that you understand this.

I would not start with such a presumption (or at least not a strong presumption) where the evidence for counterfactuality was somewhat stronger (cf. GiveWell). The reason is that the hypothetical well-informed donor probably would give some weight to a match even if they concluded it was (say) 25% counterfactual. Therefore, the fact that a donor is proceeding with a matched donation under those circumstances does not call the adequacy of their understanding into question in the same way.

I do see how this could be adversarial or uncooperative. Do X, or else I’ll stop buying medicine for dying kids. What?!

I think doing something like this could make sense and be reasonably cooperative if the marginal costs of donation were sufficiently burdensome to you (and you’d actually donate less if you weren’t trying to match). On your own, the cost-effectiveness — the benefits from your donations divided by your costs — might not look so good, but the benefits from matchees’ donations + the benefits from your donations all divided by your costs could make it seem worth taking on the extra burden to you. Then, it’s actually you and your matchee(s) cooperating to provide a public good: people or animals being better off. You’re appealing to others to take this on as a joint responsibility.

This is like people being willing to vote to ban cages and crates for farmed animals, but still buying products from caged and crated animals.

Or taxation for welfare for the poor or other public goods.