Note: During my final review of this post I came across a whole slew of posts on LessWrong and this forum from several years ago saying many of the same things. While much of this may be rehashing existing arguments, I think the fact that it’s still not part of the general discussions means it’s worth bringing up again. Full list of similar articles at the end of the post, and I’m always interested in major things I’m getting wrong or key sources I’m missing.

After a 12-week course on AI Safety, I can’t shake a nagging thought: there’s an obvious (though not easy) solution to the existential risks of AGI.

It’s treated as axiomatic in certain circles that Artificial General Intelligence is coming. Discussions focus on when, how disruptive it’ll be, and whether we can align it. The default stance is either “We’ll probably build it despite the existential risk” or “We should definitely build it, because [insert utopian vision here]”.

But a concerned minority (Control AI, Yudkowsky, Pause AI, FLI, etc.) is asking: “What if we just… didn’t?” Or, in more detail: “Given the unprecedented stakes, what if actively not building AGI until we’re far more confident in its safety is the only rational path forward?” They argue that while safe AGI might be theoretically possible, our current trajectory and understanding make the odds of getting it right the first time terrifyingly low. And since the downside isn’t just “my job got automated” but potentially “humanity is no longer in charge, or even exists”, perhaps the wisest move is to collectively step away from the button (at least for now). Technology isn’t destiny; it’s the product of human choices. We could, and I’ll argue below that we should, choose differently. The current risk-benefit calculus simply doesn’t justify the gamble we’re taking with humanity’s future, and we should collectively choose to wait, focus on other things, and build consensus around a better path forward into the future.

Before proceeding, let’s define AGI: AI matching the smartest humans across essentially all domains, possessing agency over extended periods (>1 month), running much faster than humans (5x+), easily copyable, and cheaper than human labor. This isn’t just better software; it’s a potential new apex intelligence on Earth. (Note: I know this doesn’t exist yet, and its possibility and timeline remain open questions. But insane amounts of time and money are being dedicated to trying to make it happen as soon as possible, so let’s think about whether that’s a good idea).

I. Why The Relentless Drive Towards The Precipice?

The history of technological progress has largely centered on reducing human labor requirements in production. We automate the tedious, the repetitive, the exhausting, freeing up human effort for more interesting or productive pursuits. Each new wave of automation tends to cause panic: jobs vanish, livelihoods teeter on the brink, entire industries suddenly seem obsolete. But every time so far, eventually new jobs spring up, new industries flourish, and humans end up creating value in ways we never previously imagined possible.

Now, enter Artificial General Intelligence. If AGI lives up to its premise, it’ll eventually do everything humans do, but better, cheaper, and faster. Unlike previous technologies that automated specific domains, AGI would automate all domains. That leaves us with an uncomfortable question: if AGI truly surpasses humans at everything, what economic role remains for humanity?

Yet here we are, pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into AI research and development in 2025. Clearly, investors, entrepreneurs, and governments see enormous value in pursuing this technology, even as it potentially renders human labor obsolete. Why such a paradoxical enthusiasm? Perhaps we’re betting on new and unimaginable forms of value creation emerging as they have before, or perhaps we haven’t fully grappled with the implications of what AGI might actually mean. Either way, the race is on, driven primarily by the following systemic forces:

Competition: Both evolution and capitalism ruthlessly select for competitive advantage. When a company develops a method to perform valuable work at lower cost and higher quality, competitors who fail to adapt simply perish. If a new human species emerged that never aged, thought 30% faster each year, and could instantly create adult offspring for a small fee, they would eventually dominate the labor force and ultimately the entire planet.

Money: The economic incentives here aren’t subtle. Companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and DeepMind see trillions in potential value. Pausing for careful alignment research looks like economic suicide, and even diverting resources to safety efforts that could instead be spent on capabilities is increasingly not the norm. Capitalism, great for optimizing quarterly returns, seems structurally incapable of prioritizing the survival of our species over short-term profits.

Military Supremacy: Nation‑states notice when technology moves the “win a war” slider. Autonomous weapons, cyber capabilities, intelligence analysis – the applications are endless and potentially world-altering. The fear that “the other side” will get there first creates immense pressure to accelerate, safety protocols be damned. This dynamic resembles Cold War brinkmanship, but with potentially more catastrophic consequences and harder-to-verify constraints.

Inertia & Narrative: Beyond strategic and economic drivers, there’s the sheer intellectual allure – the “can we build God?” impulse. There’s also a deeply ingrained cultural narrative that technological progress is linear, inevitable, and fundamentally good. Questioning AGI development can feel like challenging progress itself, which is a position few wish to adopt in innovation-worshipping cultures.

This confluence of factors creates a powerful coordination problem. Everyone might privately agree that racing headlong into AGI without robust safety guarantees is madness, but nobody wants to be the one who urges caution while others surge ahead.

II. Surveying The Utopian Blueprints (And Noticing The Cracks)

Many intelligent people have envisioned futures transformed by AGI, often painting pictures of abundance and progress. However, these optimistic scenarios frequently seem to gloss over the most challenging aspects, relying on assumptions that appear questionable upon closer inspection.

Dario Amodei’s Machines of Loving Grace: The idea of globally coordinated and equitably distributed AGI genius overlooks geopolitical competition, misuse by bad actors, power concentration risks, and the core alignment problem. Amodei assumes a level of global cooperation and foresight we’ve rarely, if ever, achieved on issues with far lower stakes.

Sam Altman’s Three Observations: Altman envisions “super-exponential” value creation solving all our problems, breezily asserting that “policy matters” will handle trifles like alignment, distribution, and preventing misuse. This feels less like a plan and more like hoping a magical abundance fairy will solve everything for us.

Leopold Aschenbrenner’s Situational Awareness: Aschenbrenner seems pretty sure that “superalignment… is a solvable problem.” While confidence is admirable, it’s not quite the same as having a solution. His whole framing seems very much like a Cold War redux (“the free world must prevail!”), treating power as a zero-sum game to be won, without lingering on the possibility that maybe the prize itself is bad for everyone involved, regardless of who “wins” the race.

Nick Bostrom’s Deep Utopia: Explicitly ignores the alignment and control problems to explore the philosophical landscape of a post-scarcity world where AGI caters to every whim. While an interesting thought experiment (though visions like The Metamorphosis of Prime Intellect suggest such utopias might be psychologically horrifying), the necessity of sidestepping the “how do we get there safely?” question is itself revealing. Moreover, many readers (myself included) might find his utopian vision fundamentally unsatisfying rather than aspirational.

These examples highlight a pattern: optimistic visions often depend on implicitly assuming the hardest problems (alignment, control, coordination, governance) will somehow be solved along the way.

III. Why AGI Might Be Bad (Abridged Edition)

Not all visions of an AGI future are rosy. AI-2027 offers a more sobering, and frankly terrifying, scenario precisely because it takes the coordination and alignment problems seriously. Many experts have articulated in extensive detail the numerous pathways through which AGI development might lead to catastrophe. Here’s a succinct overview, helpfully categorized by the Center for AI Safety (and recently echoed by Google’s AGI Safety framework):

Malicious use: Hostile actors deploying AI for mass destruction (e.g., terrorists leveraging AI to engineer devastating pathogens). This category should also encompass scenarios where those controlling AI impose decisions on humanity that significant segments would reject upon reflection (i.e., human non-alignment amplified by AI power).

AI race: Competitive pressures that could drive us to deploy AIs in unsafe ways, despite this being in no one’s best interest. For instance, nations increasingly delegating military decision-making to AI systems to maintain strategic parity, reducing human oversight in situations where, historically, human judgment prevented catastrophe (consider the Cuban Missile Crisis). These pressures might also accelerate the replacement of human labor across domains, resulting in gradual disempowerment.

Organizational risks: Accidents stemming from AI complexity and organizational limitations. Even industries with robust safety cultures experience occasional disasters (e.g., aviation and nuclear power). The AI industry involves less-understood technology and demonstrably lacks the safety culture and regulatory frameworks present in other high-risk domains. With AGI embedded throughout critical infrastructure, such seemingly inevitable mistakes could prove catastrophic.

Rogue AIs: Goal alignment represents a recognized challenge with current AI systems. As AI becomes more powerful and embedded in crucial systems like economies and militaries, these problems could exponentially worsen, potentially leading to uncontrollable AI behavior. Alignment remains fundamentally unsolved, and I’ve argued elsewhere that conceptualizing it as a solvable technical problem may constitute a category error.

Particularly revealing are statements from leaders of top AI laboratories who have, at various points, acknowledged that what they’re actively building could pose existential threats:

Sam Altman (CEO OpenAI): “The bad case — and I think this is important to say — is like lights out for all of us.”—Jan 2023

Dario Amodei (CEO Anthropic): “My chance that something goes really quite catastrophically wrong on the scale of human civilization might be somewhere between 10% and 25%.”—Oct 2023

Elon Musk (CEO xAI): “What are the biggest risks to the future of civilization? It is AI—it’s both positive and negative, it has great promise, great capability, but also with that comes great danger.”—Feb 2023

Demis Hassabis (CEO Google DeepMind): “We must take the risks of AI as seriously as other major global challenges, like climate change [...] It took the international community too long to coordinate an effective global response to this, and we’re living with the consequences of that now. We can’t afford the same delay with AI.”—Oct 2023

These are not the anxieties of distant observers or fringe commentators; they are sober warnings issued by those intimately familiar with the technology’s capabilities and trajectory. The list of concerned researchers, ethicists, policymakers, and other prominent figures who echo these sentiments is extensive. When individuals working at the forefront of AI development express such profound concerns about its potential risks, a critical question arises: Are we, as a society, giving these warnings the weight they deserve? And, perhaps more pointedly, shouldn’t those closest to the technology be advocating even more vociferously and consistently for caution and robust safety measures?

IV. Existence Proofs For Restraint: Sometimes, We Can Just Say No

Okay, but can we realistically stop? The feeling of inevitability is strong, but history offers counterexamples where humanity collectively balked at deploying dangerous tech:

Biological Weapons: The 1975 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) banned development and stockpiling. Driven by moral horror and proliferation fears (helped by the US unilaterally halting its offensive program), it created a strong global norm. It’s not perfect – verification is hard due to dual-use tech, and compliance hasn’t been universal (Biopreparat, anyone?). Additionally, there wasn’t any direct economic incentive and other more effective weaponry made this a relatively easy choice.

Atmospheric Nuclear Testing: Public outcry over radioactive fallout (e.g., from the Castle Bravo test) spurred the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT). This treaty significantly cut atmospheric radiation and showed that even rival superpowers could collaborate on shared existential threats. However, its relevance as a model for halting a technology is limited: it didn’t stop the nuclear arms race (testing simply moved underground) and lacked universal adoption. Crucially, with no economic drivers for atmospheric testing itself and alternative testing methods available, the PTBT represented more a redirection of nuclear development than a cessation of an entire technological trajectory.

Nukes in Space: The 1967 Outer Space Treaty banned weapons of mass destruction in orbit. Despite the obvious strategic advantages, the fear of nuclear fallout from launch failures or accidental orbits, the ease of verification (nuclear armed satellites are relatively easy to detect), and the shared desire to keep space exploration peaceful helped the US and USSR agree.

Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA (1975): When recombinant DNA emerged, scientists themselves paused certain experiments and convened to create safety guidelines. This proactive, scientist-led effort allowed the field to advance more safely, largely avoiding major public backlash or heavy-handed regulation (at least initially).

Human Cloning: Near-universal ethical revulsion post-Dolly led to widespread bans and condemnation, establishing a powerful norm even without a perfect global treaty. The long feedback cycles due to human development timelines and the moral/ethical aversion to the possibility of negative outcomes made this choice a lot easier than choosing to approach AGI with extreme caution.

For more examples of technological restraint, see this analysis, this report, and this list.

Important Caveats: These historical analogies are imperfect:

Verifying compliance with potential AGI restrictions is likely far harder than monitoring missile silos or atmospheric tests.

The dual-use problem with AI is extreme: the same hardware, algorithms, and datasets used for beneficial AI could potentially fuel dangerous AGI development.

The economic and military incentives for AGI might also dwarf those associated with past restricted technologies.

Many of these successful agreements occurred during a specific geopolitical window (roughly 1963-1975) that may have been unusually conducive to such cooperation.

As cautionary tales like Tokugawa Japan’s attempt at unilateral technological stagnation show, such efforts likely require broad international coordination to succeed long-term. Isolated restraint often just means falling behind.

Nevertheless: These examples prove that “inevitable” is a choice, not a physical law. They show that international coordination, moral concern, and national regulation can put guardrails on technology.

V. So, What’s The Alternative Path?

If the AGI highway looks like it leads off a cliff, what’s the alternative? It starts by expanding the Overton Window: making “Let’s not build AGI right now, or maybe ever” a discussable option. There are concrete policy proposals that have been put out by various people and institutions that set us down this safer path, we just need to collectively choose to walk it.

Pause All Frontier AI Development: This is the position of groups like Pause AI and Eliezer Yudkowsky, but I don’t think that it’s feasible at the moment and it’s not quite warranted just yet. Carl Shulman makes some compelling arguments here regarding:

A pause becomes more impactful the closer to AGI it occurs. (One counterpoint: the closer we are to AGI at the time of a pause, the more momentum in the industry in general and the easier it is for a defector to break ranks and cross the finish line).

If a temporary pause doesn’t “work” (i.e., give us the time to conclusively solve the existential risks or build robust governance), then future calls for pauses become less likely due to a “Boy Who Cried Wolf” effect.

A pause would only be helpful if it was universal or nearly so, otherwise it just is a minor delay by removing some of the force pushing accelerating capabilities.

There are more impactful, less costly, and more likely to work actions that could be taken on a policy front, and we should prioritize those.

However, this doesn’t negate the value of the “pause” concept entirely. A more promising approach might be to build broad consensus now that certain future developments or warning signs would warrant a coordinated, global pause. If there’s No Fire Alarm for AGI, perhaps the immediate task is to build the political and institutional groundwork necessary to install one (agreeing on what triggers it and how we would respond) before the smoke appears.

Focus on Non-Existential AI: Anthony Aguirre’s framework in “Keep the Future Human” seems useful: develop AI that is Autonomous, General, or Intelligent, maybe even two out of three, but avoid systems that master all three. We can build incredibly powerful tools and advisors without building autonomous agents that could develop inscrutable goals.

The “AGI Venn Diagram” from Anthony Aguirre, proposing a tiered framework for evaluating and regulating AI systems.

Intelligent: AlphaFold (predicting protein structures).

Intelligent + Autonomous: Self-driving cars (still struggling, notably).

Intelligent + General: Current large language models like Claude or GPT-4 (useful, but not agentic planners).

This “tool AI” path offers enormous benefits – curing diseases, scientific discovery, efficiency gains – without the same existential risks. It prioritizes keeping humans firmly in control.

Focus on Defensive Capabilities: Vitalik Buterin’s “d/acc: decentralized and democratic, differential defensive acceleration” concept offers another framing. Buterin makes a good point that regulation is often too slow to keep up and might target the wrong things (e.g., focusing only on training compute when inference compute is also becoming critical). He pushes instead for liability frameworks or hardware controls, but above all, focusing development on capabilities that make humanity more robust and better able to defend itself. Helen Toner has made an excellent case for why we should focus some amount of our efforts here regardless. She notes that as AI capabilities become cheaper and more accessible over time, the potential for misuse inevitably grows, necessitating robust defenses. The folks at Forethought also recently released an excellent paper pointing towards specific areas of development that would be especially helpful in navigating the coming existential risks.

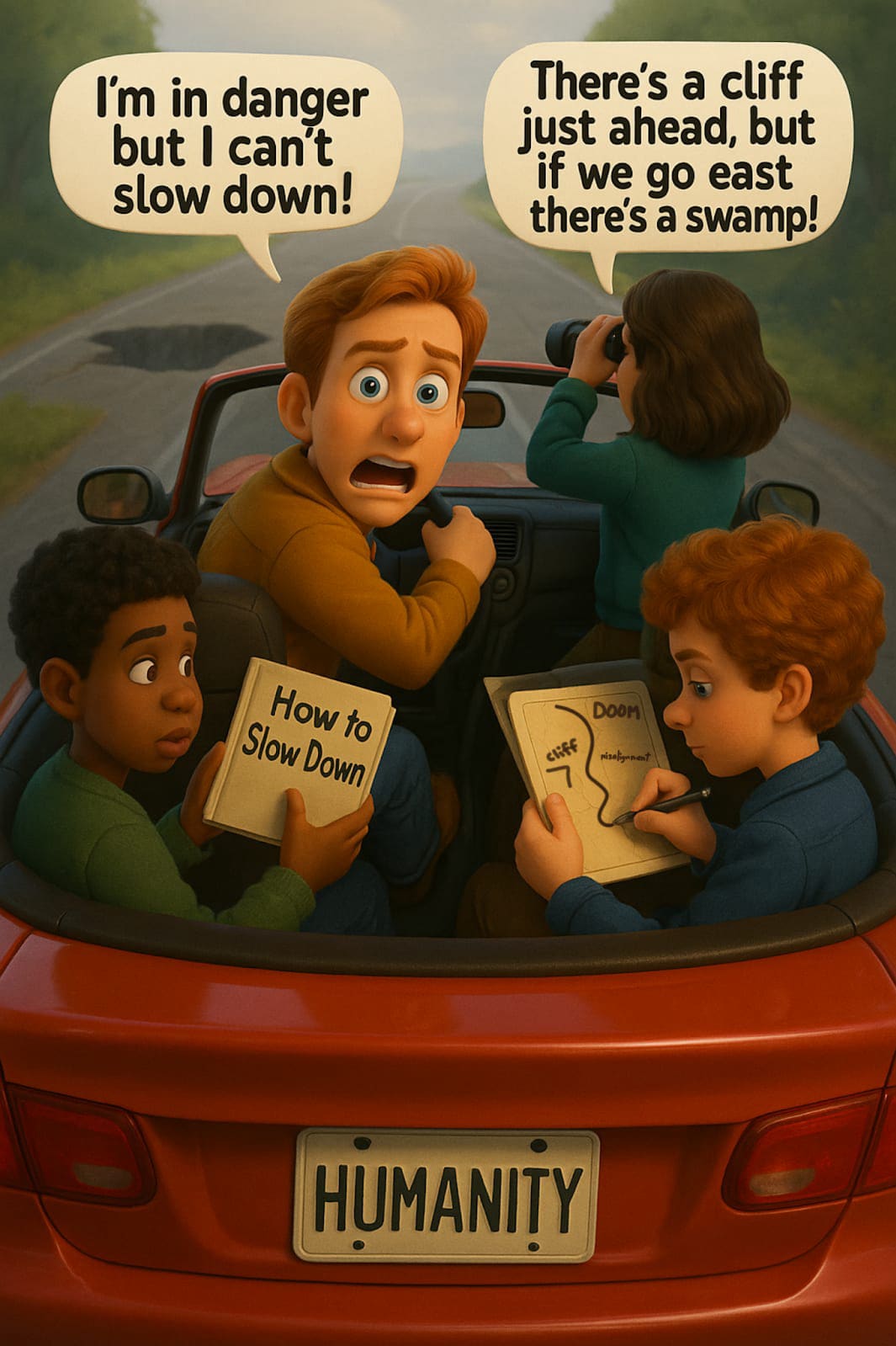

A stylized version of Vitalik Buterin’s catchy image of humanity’s current state.

Unfortunately, just how to ensure that no critical mass of actors choose one of the three “bad” paths above is left as an exercise for the reader.

What We Should Do (For Various Scopes of “We”):

Globally: Serious international talks are needed, moving beyond pleasantries to binding agreements. Could we govern access to the massive compute clusters necessary for training and running frontier models? Shared monitoring, international safety standards, and agreements on capability thresholds should all be on the table. The first step is picking up the phone (US and China, looking at you). The next is agreeing on the critical risks and finding common ground, ideally focusing on strategies that clearly benefit everyone. Neither country wants rogue actors getting major boosts to CBRN capabilities, power concentrated uncontrollably in a single corporation, or a misaligned intelligent AI. More serious attempts should be made at drafting international treaties and establishing norms.

Nationally: Mandatory safety evaluations, transparency requirements, liability frameworks, mandating whistle-blower protections and a significant shift in government funding towards safety research and “tool AI” rather than just frontier capabilities. The US legislative branch is not known for its speed these days, so focusing on aspects attractive across party lines is key (transparency seems like a good candidate). Export controls on AI chips should continue and update as key bottlenecks become clearer. We need to get executive and legislative leadership up to speed on the key risks we’re facing so that discussions can shift to how and when to address them.

State Level: Given the federal gridlock, state-level legislation might be a more likely path, potentially serving as templates for federal action later. The same principles apply: get state politicians on board with the general idea, then focus regulations on reducing catastrophic and existential risks. While some attempts have been good (like California’s SB 1047), many others (like the proposals in Texas or the EU AI Act) have focused mostly or entirely on short-term, mundane harms better addressed by existing laws.

Corporate Level: AI companies need real internal governance, serious investment in safety (not just safety PR), transparency, and willingness to pause if safety benchmarks aren’t met. Most leading AI companies are already part of the Frontier Model Forum, which is a good start for aligning on safety commitments. Instead of moving to erase the excellent “stop competing and start assisting” clause from its charter, OpenAI and other leading AI companies should be clarifying and strengthening such industry-wide agreements and norms around responsible development and restraint.

Individually: Engage in informed discussion, raise awareness about the stakes, and advocate for sensible policy. Reach out to your senators and representatives. If you work in AI, prioritize safety, speak up internally, and refuse to build differentially offensive or dangerous capabilities. Demand action from leaders and politicians.

VI. Addressing The Inevitable Objections

Any argument for slowing or stopping AGI development inevitably encounters pushback. Yoshua Bengio, one of the “Godfathers of AI” has written eloquently about the arguments against taking AI Safety seriously, but I’ll quickly address some of the most common:

“It’s inevitable! Stop being a Luddite!” History shows technological trajectories are not predetermined laws of physics. And this isn’t smashing looms; it’s questioning whether building potentially self-replicating, superintelligent loom-operators we can’t control is wise. As Katja Grace put it so eloquently, “If you think AGI is highly likely to destroy the world, then it is the pinnacle of shittiness as a technology. Being opposed to having it into your techno-utopia is about as luddite as refusing to have radioactive toothpaste there.”

“We NEED AGI to solve X (climate, cancer)!” Do we? Or can advanced narrow AI achieve much of this? The potential benefits of AGI are immense, but the potential cost is literally everything. Risk management suggests exploring safer paths first. If your house is on fire, you don’t reach for the experimental fusion-powered fire extinguisher that might also level the city.

“Coordination is impossible! Someone will cheat!” Hard, yes. Impossible? Arms control shows partial success is achievable. Assuming impossibility is self-fulfilling. The harder it is, the more urgent it is to start trying. And how difficult cooperation is really depends on the exact details of the game theoretical situation, which are extremely unclear.

“Pausing harms innovation! Bad actors win!” The proposal isn’t stopping all AI, but steering away from the AGI cliff as we frantically convince the driver(s) that we are in fact speeding towards a cliff. Safer AI innovation can flourish. And if alignment is unsolved, any AGI is a potential catastrophe, regardless of who builds it first.

“This is just Big Tech trying to lock out competition (regulatory capture)!” A valid concern. Regulations must be designed carefully. But the core risks are highlighted by many independent academics and non-profit researchers, not just incumbents. And much of the proposed regulations would only apply to Big Tech themselves, not small startups or open source models. We can fight regulatory capture while still taking the existential risks seriously.

“If we don’t, China/[insert adversary] will!” The geopolitical race dynamic is real and dangerous. But again, see arms control. Treaties, export controls, mutual deterrence – these tools exist. Making the danger clear enough to overcome rivalry is the challenge. A world where only China has AGI might be bad; a world where anyone has misaligned AGI could be worse.

VII. Conclusion: Choosing Not To Roll The Dice

Maybe safe AGI is possible. Maybe scaling laws will hit a ceiling sooner than we think, or we’ll run out of compute/energy before models get dangerously capable. Maybe alignment is easier than it looks. Maybe the upsides justify the gamble.

I am increasingly skeptical.

The argument here isn’t that stopping AGI development is easy or guaranteed, or even that we need to do it right now. It’s that not developing AGI until we’re confident that it’s a good idea is a coherent, rational, and drastically under-discussed strategic option for humanity. It’s risk management applied to the ultimate tail risk.

Instead of accelerating towards a technology we don’t understand, can’t reliably control, and whose many failure modes could be terminal, driven by competition and fear… perhaps we should coast for a bit, and prepare to hit the brakes. Perhaps we should invest our considerable resources and ingenuity into developing AI that demonstrably empowers humanity, into rigorously mapping the potential failure modes of advanced AI, and into building the global consensus and governance structures needed to navigate the path ahead safely, rather than blindly racing towards a potential existential cliff.

Sometimes, the smartest thing to build is a brake (and the consensus that we need one).

List of articles and posts advocating similar things for similar reasons:

Let’s think about slowing down AI — LessWrong (this one was particularly in depth and compelling)

What an actually pessimistic containment strategy looks like — LessWrong

Slowing down AI progress is an underexplored alignment strategy — EA Forum

I love to see people coming to this simple and elegant case in their own way and from their own perspective— this is excellent for spreading the message and helps to keep it grounded. Was very happy to see this on the Forum :)

As for whether Pause is the right policy (I’m a founder of PauseAI and ED of PauseAI US), we can quibble about types of pauses or possible implementations but I think “Pause NOW” is the strongest and clearest message. I think anything about delaying a pause or timing it perfectly is the unrealistic thing that makes it harder to achieve consensus and to have the effect we want, and Carl should know better. I’m still very surprised he said it given how much he seems to get the issue, but I think it comes down to trying to “balance the benefits and the risks”. Imo the best we can do for now is slam the brakes and not drive off the cliff, and we can worry about benefits after.

When we treat international cooperation or a moratorium as unrealistic, we weaken our position and make that more true. So, at least when you go to the bargaining table, if not here, we need to ask for fully what we want without pre-surrendering. “Pause AI!”, not “I know it’s not realistic to pause, but maybe you could tap the brakes?” What’s realistic is to some extent what the public says is realistic.

On my view the OP’s text citing me left out the most important argument from the section they linked: the closer and tighter an AI race is at the international level as the world reaches strong forms of AGI and ASI, the less slack there is for things like alignment. The US and Chinese governments have the power to prohibit their own AI companies from negligently (or willfully) racing to create AI that overthrows them, if they believed that was a serious risk and wanted to prioritize stopping it. That willingness will depend on scientific and political efforts, but even if those succeed enormously, the international cooperation between the US and China will pose additional challenges. The level of conviction in risks governments would need would be much higher than to rein in their own companies without outside competition, and there would be more political challenges.

Absent an agreement with enough backing it to stick, slowdown by the US tightens the international gap in AI and means less slack (and less ability to pause when it counts) and more risk of catastrophe in the transition to AGI and ASI. That’s a serious catastrophe-increasing effect of unilateral early (and ineffectual at reducing risk) pauses. You can support governments having the power to constrain AI companies from negligently destroying them, and international agreements between governments to use those powers in a coordinated fashion (taking steps to assure each other in doing so), while not supporting unilateral pause to make the AI race even tighter.

I think there are some important analogies with nuclear weapons. I am a big fan of international agreements to reduce nuclear arsenals, but I oppose the idea of NATO immediately destroying all its nuclear weapons and then suffering nuclear extortion from Russia and China (which would also still leave the risk of nuclear war between the remaining nuclear states). Unilateral reductions as a gesture of good faith that still leave a deterrent can be great, but that’s much less costly than evening up the AI race (minimal arsenals for deterrence are not that large).

“So, at least when you go to the bargaining table, if not here, we need to ask for fully what we want without pre-surrendering. “Pause AI!”, not “I know it’s not realistic to pause, but maybe you could tap the brakes?” What’s realistic is to some extent what the public says is realistic.”

I would think your full ask should be the international agreement between states, and companies regulated by states in accord with that, not unilateral pause by the US (currently leading by a meaningful margin) until AI competition is neck-and-neck.

And people should consider both the possibilities of ultimate success and of failure with your advocacy, and be wary of intermediate goals that make things much worse if you ultimately fail with global arrangements but make them only slightly more likely to succeed. I think it is certainly possible some kind of inclusive (e.g. including all the P-5) international deal winds up governing and delaying the AGI/ASI transition, but it is also extremely plausible that it doesn’t, and I wouldn’t write off consequences in the latter case.

I agree this mechanism seems possible, but it seems far from certain to me. Three scenarios where it would be false:

One country pauses, which gives the other country a commanding lead with even more slack than anyone had before.

One country pauses, and the other country, facing reduced incentives for haste, also pauses.

One country pauses, which significantly slows down the other country also, because they were acting as a fast-follower, copying the models and smuggling the chips from the leader.

A intuition-pump I like here is to think about how good it would be if China credibly unilaterally paused, and then see how many of these would also apply to the US.

Sure, these are possible. My view above was about expectations. #1 and #2 are possible, although look less likely to me. There’s some truth to #3, but the net effect is still gap closing, and the slowing tends to be more earlier (when it is less impactful) than later.

(Makes much more sense if you were talking about unilateral pauses! The PauseAI pause is international, so that’s just how I think of Pause.)

Right, those comments were about the big pause letter, which while nominally global in fact only applied at the time to the leading US lab, and even if voluntarily complied with would not affect the PRC’s efforts to catch up in semiconductor technology, nor Chinese labs catching up algorithmically (as they have partially done).

Thanks for the comments Holly! Two follow-ups:

The PauseAI website says “Individual countries can and should implement this measure right now.” Doesn’t that mean that they’re advocating for unilateral pausing, regardless of other actors choices, even if the high level/ideal goal is a global pause?

If all of the important decision makers (globally) agreed on the premise that powerful AI/AGI/ASI is too risky, then I think there would still be a discussion around aligning on how close we are, how close we should be when we pause, how to enforce a pause, and when it would be safe to un-pause. But to even get to that point, you need to convince those people of the premise, so it seems pre-emptive to me to focus the messaging on the pause aspect if the underlying reasons for the pause aren’t agreed upon. So something more like “We should pause global AI development at some point/soon/now, but only if everyone stops at once, because if we get AGI right now we’re probably doomed, because [insert arguments here]”. But it sounds like you think that messaging is perhaps too complex and it’s beneficial to simplify it to just “Pause NOW”?

(FYI I’m the ED of PauseAI US and we have our own website pauseai-us.org)

1. It is on every actor morally to do the right thing by not advancing dangerous capabilities separate from whether everyone else does it, even though everyone pausing and then agreeing to safe development standards is the ideal solution. That’s what that language refers to. I’m very careful about taking positions as an org, but, personally, I also think unilateral pauses would make the world safer compared to no pauses by slowing worldwide development. In particular, if the US were to pause capabilities development, our competitors wouldn’t have our frontier research to follow/imitate, and it would take other countries longer to generate those insights themselves.

2. “PauseAI NOW” is not just the simplest and best message to coordinate around, it’s also an assertion that we are ALREADY in too much danger. You pause FIRST, then sort out the technical details.

Thanks for the thoughtful feedback Carl, I appreciate it. This is one of my first posts here so I’m unsure of the norms—is it acceptable/preferred that I edit the post to add that point to the bulleted list in that section (and if so do I add a “edited to add” or similar tag) or just leave it to the comments for clarification?

I hope the bulk of the post made it clear that I agree with what you’re saying—a pause is only useful if it’s universal, and so what we need to do first is get universal agreement among the players that matter on why, when, and how to pause.

I dispute that we’re facing a coordination problem in the sense you described. Chad Jones’ paper is a helpful comparison here to illustrate AI racing dynamics.

His model starts from the observation that the very same actors who might enjoy benefits from faster AI also face the extinction hazard that faster AI could bring. In his social-planner formulation, the idea is to pick an R&D pace that equates the marginal gain in permanent consumption growth with the marginal rise in a one-time extinction probability[1]; when the two curves cross, that is the point you stop. Nothing in the mechanism lets one party obtain the upside while another bears the downside of existential risk, so the familiar logic of a classic tragedy of the commons—”If I restrain myself, someone else will defect and stick me with the loss”—doesn’t apply. The optimal policy is simply to pick whatever pace of development makes the risk–reward ratio come out favorable.

Why is that a realistic way to view today’s situation? First, extinction risk is highly non-rival: if an unsafe system destroys the world, it wipes out everyone, including the engineers and investors who pushed the system forward. They cannot dump that harm on an outside group the way a factory dumps effluent into a river. Second, the primary benefits—higher incomes and earlier biomedical breakthroughs—are also broadly shared; they are not gated to the single lab that crosses the finish line first. Because both tails of the distribution are so widely spread, each lab’s private calculus already contains a big slice of the social calculus.

Third, empirical incentives inside frontier labs look far more like “pick your preferred trade-off” than “cheat while others cooperate.” Google, Anthropic, OpenAI, and their peers hold billions of dollars in equity that vaporizes if a catastrophic failure occurs; their founders and employees live in the metaphorical blast radius just like everyone else.

So why does it look in practice as though labs are racing? The Jones model suggests the answer is epistemic, not game-theoretic. Different actors slot in different parameter values for how much economic growth matters or how sharply risk rises with capability, and those disagreements lead to divergent optimal policies. That is a dispute over facts and forecasts, not a coordination failure in the classic tragedy-of-the-commons sense, where each player gains by defecting even though all would jointly prefer restraint.

He technically models the problem as a choice of when to stop, rather than strictly picking a pace of R&D. However, for the purpose of this analysis, the difference between these two ways of modeling the problem is largely irrelevant.

“Second, the primary benefits—higher incomes and earlier biomedical breakthroughs—are also broadly shared; they are not gated to the single lab that crosses the finish line first.”

If you look at the leaders of major AI companies you see people like Elon Musk and others who are concerned with getting to AGI before others who they distrust and fear. They fear immense power in the hands of rivals with conflicting ideologies or in general.

OpenAI was founded and funded in significant part based on Elon Musk’s fear of the consequences of the Google leadership having power over AGI (in particular in light of statements suggesting producing AI that lead to human extinction would be OK). States fear how immense AGI power will be used against them. Power, including the power to coerce or harm others, and relative standing, are more important there than access to advanced medicine or broad prosperity for the competitive dynamics.

In the shorter term, an AI company whose models are months behind may find that their APIs have negative margins while competitors earn 50% margins. Avoiding falling behind is increasingly a matter of institutional survival for AI companies, and a powerful motive to increment global risk a small amount to profit rather than going bankrupt.

The motive I see to take incremental risk is “if AI wipes out humanity I’m just as dead either way, and my competitors are similarly or more dangerous than me (self-serving bias plays into this) but there are huge ideological or relative position (including corporate survival) gains from control over powerful AGI that are only realized by being fast, so I should take a bit more risk of disaster conditional on winning to raise the chance of winning.” This dynamic looks to apply to real AI company leaders who claim big risks of extinction while rushing forward.

With multiple players doing that, the baseline level of risk from another lab goes up, and the strategic appeal of incrementing it one more time for relative advantage continues. You can get up to very high levels of risk perceived by labs that way, accepting each small increment of risk as minor compared to the risk posed by other labs and the appeal of getting a lead, setting a new worse baseline for others to compete against.

And the epistemic variation makes it all worse, where the most unconcerned players set a higher baseline risk spontaneously.

Musk is a vivid example of the type of dynamic you’re describing, but he’s also fairly unusual in this regard. Sundar Pichai, Satya Nadella, and most other senior execs strike me as more like conventional CEOs: they want market share, profits, and higher margins, but they’re not seeking the kind of hegemonic control that would justify accepting a much higher p(doom). If the dominant motive is ordinary profit maximization rather than paranoid power-seeking, then my original point stands: both the upside (huge profit streams) and the downside (self-annihilation) accrue to the people pushing AI forward, so the private incentives already internalize a large chunk of the social calculus.

Likewise, it’s true that governments often seek hegemonic control over the world in a way that creates destructive arms races, but even in the absence of such motives, there would still be a strong desire among humans to advance most technologies to take advantage of the benefits.

The most important fact here is that AI has an enormous upside: people would still have strong reasons to aggressively seek it to obtain life extension and extraordinary wealth even in the absence of competitive dynamics—unless they were convinced that the risk from pursuing that upside was unacceptably high (which is an epistemic consideration, not a game-theoretic trap).

You may have misread me here. I’m not claiming that AI labs are motivated by a desire to create broad prosperity. They certainly do care about “power,” but the key question is whether they’re primarily driven by the type of zero-sum, adversarial power-seeking you described. I’m skeptical that this is the dominant motive. Instead, I think ordinary material incentives likely play a larger role.

The unilateralist’s curse is primarily worrisome when the true value of an initiative is negative; for good projects it usually helps them proceed. Moreover, if good projects can be vetoed (e.g., via regulators), this creates a reverse curse that can block beneficial progress. Ultimately I don’t see a strong argument for a trap that forces AI to advance forward at everyone’s expense. We aren’t really at the mercy of Moloch here. The main story is that other people simply assign (a) lower extinction probabilities or (b) higher weight to the upside potential than EAs tend to. That is a rather ordinary disagreement over facts and values, not a real curse.

I think there’s some talking past each other happening.

I am claiming that there are real coordination problems that lead even actors who believe in a large amount of AI risk to think that they need to undertake risky AI development (or riskier) for private gain or dislike of what others would do. I think that dynamic will likely result in future governments (and companies absent government response) taking on more risk than they otherwise would, even if they think it’s quite a lot of risk.

I don’t think that most AI companies or governments would want to create an indefinite global ban on AI absent coordination problems, because they think benefits exceed costs, even those who put 10%+ on catastrophic outcomes, like Elon Musk or Dario Amodei (e.g. I put 10%+ on disastrous outcomes from AI development but wouldn’t want a permanent ban, even Eliezer Yudkowsky doesn’t want a permanent ban on AI).

I do think most of the AI company leadership that actually believes they may succeed in creating AGI or ASI would want to be able to take a year or two for safety testing and engineering if they were approaching powerful AGI and ASI absent issues of commercial and geopolitical competition (and I would want that too). And I think future US and Chinese governments, faced with powerful AGI/ASI and evidence of AI misbehavior and misalignment, would want to do so save for geopolitical rivalry.

Faced with that competition each actor taking a given level of risk to the world doesn’t internalize it, only the increment of risk over their competitor. And companies and states both get a big difference in value from being incrementally ahead vs behind competitors. For companies it can be huge profits vs bankruptcy. For states (and several AI CEOs who actually believe in AGI and worry about how others would develop and use it, I agree most of the hyperscaler CEOs and the like are looking at things from a pure business perspective and don’t even believe in AGI/ASI) there is the issue of power (among other non-financial motives) as a reason to care about being first.

Perhaps I overstated some of my claims or was unclear. So let me try to be more clear about my basic thesis. First of all, I agree that in the most basic model of the situation, being slightly ahead of a competitor can be the decisive factor between going bankrupt and making enormous profits. This creates a significant personal incentive to race ahead, even if doing so only marginally increases existential risk overall. As a result, AI labs may end up taking on more risk than they would in the absence of such pressure. More generally, I agree that without competition—whether between states or between AI companies—progress would likely be slower than it currently is.

My main point, however, is that these effects are likely not strong enough to justify the conclusion that the socially optimal pace of AI R&D is meaningfully slower than the current pace we in fact observe. In other words, I’m not convinced that what’s rational from an individual actor’s perspective diverges greatly from what would be rational from a collective or societal standpoint.

This is the central claim underlying my objection: if there is no meaningful difference between what is individually rational and what is collectively rational, then there is little reason to believe we are facing a tragedy-of-the-commons scenario as suggested in the post.

To sketch a more complete argument here, I would like to make two points:

First, while some forces incentivize speeding up AI development, others push in the opposite direction. Measures like export controls, tariffs, and (potentially) future AI regulations can slow down progress. In these cases, the described dynamic flips: the global costs of slowing down are shared, while the political rewards—such as public credit or influence—are concentrated among the policymakers or lobbyists who implement the slowdown.

Second, as I’ve mentioned, a large share of both the risks and benefits of AI accrue directly to those driving its development. This alignment of incentives gives them a reason to avoid reckless acceleration that would dramatically increase risk.

As a testable prediction of my view, we could ask whether AI labs are actively lobbying for slower progress internationally. If they truly preferred collective constraint but felt compelled to move forward individually, we would expect them to support measures that slow everyone down—while personally moving forward as fast as they can in the meantime. However, to my knowledge, such lobbying is not happening. This suggests that labs may not, in fact, collectively prefer significantly slower development.

Great point, thanks Matthew, upon reflection I agree that the section you quoted isn’t quite accurate. I guess I would restate it as something like “This confluence of factors creates incredibly powerful incentives to not think too hard about potential downsides of this new technology we’re racing towards. Motivated reasoning is much more likely when the motivations are so strong and the risks (while large) diffuse, distant (perhaps) and uncertain.” Does that make more sense?

I guess I do still think there are aspects of the situation that I would still call a coordination problem though. Imagine a situation where there are two actors, each agree that pushing a button has a 10% chance of killing them both, if it doesn’t kill them then the button-pusher gets $1 million, and each time it gets pushed the probability of the next push killing them both goes up by 10%. They each agree on the facts of the situation, but there is an incentive to defect first if you believe the other actor might defect, right? See this o3 analysis of the situation for more math than I can summon at this time of night 😅

There are psychological pressures that can lead to motivated reasoning on both sides of this issue. On the pro-acceleration side, individuals may be motivated to downplay or dismiss the potential risks and downsides of rapid AI development. On the other side, those advocating for slowing or pausing AI progress may be motivated to dismiss or undervalue the possible benefits and upsides. Because both the risks and the potential rewards of AI are substantial, I don’t see a compelling reason to assume that one side must be much more prone to denial or bias than the other.

At most, I see a simple selection effect: the people most actively pushing for faster AI development are likely those who are least worried about the risks. This could lead to a unilateralist curse, where the least concerned actors push capabilities forward despite a high risk of disaster. But the opposite scenario could also happen, if the most concerned actors are able to slow down progress for everyone else, delaying the benefits of AI unacceptably. Whether you should care more about the first or second scenario depends on your judgement of whether rapid AI progress is good or bad overall.

Ultimately, I think it’s more productive to frame the issue around empirical facts and value judgments: specifically, how much risk rapid AI development actually introduces, and how much value we ought to place on the potential benefits of rapid development. I find this framing more helpful, not only because it identifies the core disagreement between accelerationists and pause advocates, but also because I think it better accounts for the pace of AI development we actually observe in the real world.

I agree that it seems like a valuable framing, thanks Matthew.

Thank you for writing this!

Id like to selfishly point to a previous post I’ve written on this point: Sometimes, We Can Just Say No

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/WfodoyjePTTuaTjLe/efficacy-of-ai-activism-have-we-ever-said-no

You might find it interesting to compare notes :P

On this note, the Future of Life Foundation (headed by Anthony Aguirre, mentioned in this post) is today launching a fellowship on AI for Human Reasoning.

Why? Whether you expect gradual or sudden AI takeoff, and whether you’re afraid of gradual or acute catastrophes, it really matters how well-informed, clear-headed, and free from coordination failures we are navigating into and through AI transitions. Just the occasion for human reasoning uplift!

12 weeks, $25-50k stipend, mentorship, and potential pathways to future funding and impact. Applications close June 9th.

One concept worth exploring is techno-utopianism, which may have influenced the ideology behind effective altruism. Some effective altruists appear to treat a future in which we fail to develop advanced, transhumanist versions of ourselves as an existential risk. This perspective could help explain why their focus often centers exclusively on scenarios where AGI is successfully developed.

Executive summary: This exploratory argument challenges the perceived inevitability of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) development, proposing instead that humanity should consider deliberately not building AGI—or at least significantly delaying it—given the catastrophic risks, unresolved safety challenges, and lack of broad societal consensus surrounding its deployment.

Key points:

AGI development is not inevitable and should be treated as a choice, not a foregone conclusion—current discussions often ignore the viable strategic option of collectively opting out or pausing.

Multiple systemic pressures—economic, military, cultural, and competitive—drive a dangerous race toward AGI despite widespread recognition of existential risks by both critics and leading developers.

Utopian visions of AGI futures frequently rely on unproven assumptions (e.g., solving alignment or achieving global cooperation), glossing over key coordination and control challenges.

Historical precedents show that humanity can sometimes restrain technological development, as seen with biological weapons, nuclear testing, and human cloning—though AGI presents more complex verification and incentive issues.

Alternative paths exist, including focusing on narrow, non-agentic AI; preparing for defensive resilience; and establishing clear policy frameworks to trigger future pauses if certain thresholds are met.

Coordinated international and national action, corporate accountability, and public advocacy are all crucial to making restraint feasible—this includes transparency regulations, safety benchmarks, and investing in AI that empowers rather than endangers humanity.

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.