Will we get automated alignment research before an AI Takeoff?

TLDR: Will AI-automation first speed up capabilities or safety research? I forecast that most areas of capabilities research will see a 10x speedup before safety research. This is primarily because capabilities research has clearer feedback signals and relies more on engineering than on novel insights. To change this, researchers should now build and adopt tools to automate AI Safety research, focus on creating benchmarks, model organisms, and research proposals, and companies should grant differential access to safety research.

Epistemic status: I spent ~ a week thinking about this. My conclusions rely on a model with high uncertainty, so please take them lightly. I’d love for people to share their own estimates about this.

The Ordering of Automation Matters

AI might automate AI R&D in the next decade and thus lead to large increases in AI progress. This is extremely important for both the risks (eg an Intelligence Explosion) and the solutions (automated alignment research).

On the one hand, AI could drive AI capabilities progress. This is a stated goal of Frontier AI Companies (eg OpenAI aims for a true automated AI researcher by March of 2028), and it is central to the AI 2027 forecast. On the other hand, AI could help us to solve many AI Safety problems. This seems to be the safety plan for some Frontier AI Companies (eg OpenAI’s Superalignment team aimed to build “a roughly human-level automated alignment researcher”), and prominent AI Safety voices have argued that this should be a priority for the AI safety community.

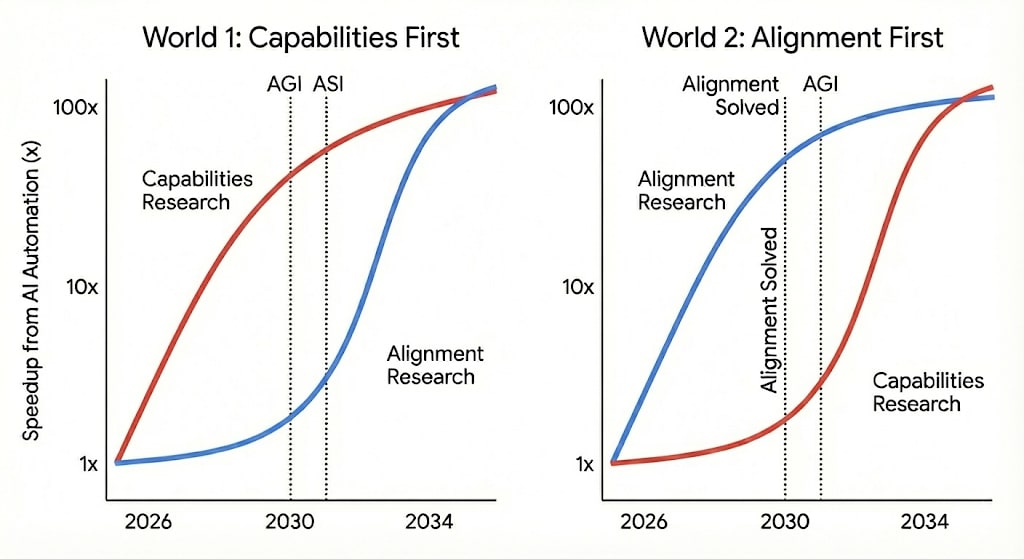

I argue that it will matter tremendously in which order different areas of ML research will be automated and, thus, which areas will see large progress first. Consider these two illustrative scenarios:

World 1: In 2030, AI has advanced to speeding up capabilities research by 10x. We see huge jumps in AI capabilities in a single year, comparable to those between 2015-2025. However, progress on AI alignment turns out to be bottlenecked by novel, conceptual insights and has fewer clear feedback signals. Thus, AI Alignment research only sees large speedups in 2032. There is some progress in AI Alignment, but it now lags far behind capabilities.

World 2: In 2030, AI is capable of contributing to many areas of AI research. This year sees massive progress in AI Safety research, with key problems in alignment theory and MechInterp being solved. However, progress in AI capabilities mostly depends on massive compute scale-ups. Thus, capabilities research doesn’t benefit much from the additional labour and continues at the same pace. In 2032, when AI is capable of significantly accelerating progress in AI capabilities, key problems in AI Safety have already been solved.

World 2 seems a lot safer than World 1, because safety problems are solved before they are desperately needed. But which world are we heading toward? To forecast this, I ask:

In which order will different areas of ML R&D experience a 10x speedup in progress due to AI compared to today?

Some clarifications on the question:

You can think about this 10x speedup as: The progress a field would make in 10 years with current tools will be made in 1 year with the help of AI.

For a 10x speedup, full automation is not necessary. It can mean that some labour-intensive tasks are automated, making researchers more efficient, or that the quality of research increases.

To make things easier, I don’t aim to forecast dates, but simply the ordering between different areas.

The 10x number is chosen arbitrarily. What actually matters is cumulative progress, not crossing an arbitrary speedup threshold. However, for any factor between 2x − 30x my conclusions would stay roughly the same.

Some other relevant forecasts include:

METR and FRI: domain experts gave a 20% probability for 3x acceleration in AI R&D by 2029, while superforecasters gave 8%.

Forethought: estimates ~60% probability of compressing more than 3 years of AI progress into <1 year after full automation of AI R&D.

AI Futures Project: Predicts that a superhuman coder/AI researcher could speed up Algorithmic Progress by 10x in December 2031.

However, none of these forecasts break down automation by research area—they treat AI R&D as a monolithic category rather than distinguishing different research areas or considering differential acceleration of safety vs capabilities research.

Methodology

How can we attempt to forecast this? I focus on 7 factors that make an area more or less amenable to speedups from automation and evaluate 10 research areas on those (5 safety; 5 capabilities).

My approach was to determine factors that indicate whether an area is more or less amenable to AI-driven speedups. For this, I drew on some previous thinking:

Carlsmith emphasises feedback quality as a critical factor: “Number-go-up” research with clear quantitative metrics (easiest), “normal science” with empirical feedback loops (medium), and “conceptual research” that relies on “just thinking about it” (hardest). Additionally, he warns that scheming AIs could undermine progress on alignment research specifically.

Hobbhahn identifies task structure, clear objectives, and feedback signals as key factors. Some safety work is easier to automate (red teaming, evals) while other areas are harder (threat modeling, insight-heavy interpretability).

Epoch’s interviews with ML researchers found consensus that near-term automation would focus on implementation tasks rather than hypothesis creation.

I determined these 7 factors as most important and scored each research area on them:

Task length: How long are the tasks in this research area? Tasks here are units that cannot usefully be broken down anymore. Shorter tasks are better as they will be automatable earlier.

Insight/creativity vs engineering/routine: LLMs are currently better at routine tasks and at engineering. They are less good at coming up with new insights and being creative.

Data availability: AIs can be trained on the data of a research area to improve performance. If an area has more existing papers and open codebases an AI should be better at it.

Feedback quality/verifiability: Are there clear, easily available criteria for success and failure? In some areas progress has clear metrics, while for others it’s harder to tell whether progress was made. Number-go-up science is easier to automate. Additionally, easy verification of success makes it possible to build RL loops that can further improve performance.

Compute vs labour bottlenecked: If progress is mostly bottlenecked by having more compute, then additional labour may cause less of a speedup. [On the other hand, additional labour might help use available compute more efficiently by designing better experiments or unlocking efficiency gains in training/inference]

Scheming AIs: Misaligned AI systems used for AI R&D might intentionally underperform or sabotage the research. In this case we might still be able to get some useful work out of them, but it would be harder.

AI Company incentive for automation: AI Companies might care more about progress in some research areas than others and would thus be willing to spend more staff time, compute and money into setting up AIs to speed up this area.

In the comments, Ben West suggested that “Importance of quantity over quality” is another important factor, and I agree. Some research areas have tasks where mediocre outputs that could be false do not cause damage or are even beneficial, while others only progress from brilliant ideas. I didn’t include this factor in my model, and it didn’t affect my conclusions.

I assigned a weight for each of these factors according to how important I judge them to be. Next, for each factor and each research area I estimated a value from 1-10 (where 10 means it is more amenable to automation). I then combine them into a weighted sum to estimate how amenable a research area is to an AI-enabled speedup.

I only focus on 10 areas, of which the first 5 are considered “AI Safety” while the other 5 improve “AI Capabilities”:

Interpretability

Alignment Theory

Scalable Oversight

AI Control

Dangerous Capability Evals

Pre-training Algorithmic Improvements

Post-training methods Improvements

Data generation/curation

Agent scaffolding

Training/inference efficiency

These are supposed to be representative of some important areas of AI Safety and some areas critical to improved Frontier AI capabilities. This is simplifying because no area neatly fits into the safety/capabilities buckets, and because there might be specific problems in an area that are more/less amenable to automation. Additionally, I don’t take into account that some problems might get harder over time, because adversaries get stronger or low hanging fruit is picked. It’s not necessary for all safety areas to be sped up before all capabilities areas, but the more overall safety research sees progress before capabilities areas, the better.

I arrived at values per factor for each area by:

Skimming a sample of papers and reading Deep Research reports about the day-to-day work in each area before making a 1-10 judgement. For data availability, I took into account the number of papers on GoogleScholar for relevant keywords, and for insight/creativity, I had Claude Haiku 4.5 rate 10 papers per area.

Asking Claude, Gemini, and ChatGPT to give ratings for each area & factor from 1-10

Average those estimates into the final number. I put a 5⁄3 weight on my judgments compared to the ensemble of AIs.

Weaknesses of the method: My conclusions are sensitive to the factor weights, and I am quite uncertain about them. I’m uncertain about the values I assigned per research area. Additionally, advances in AI capabilities might unlock large speedups across all research areas nearly simultaneously, making it less important which research areas see gains from automation earlier. Further, I don’t take into account factors such as (1) how parallelizable work is, (2) what human bottlenecks there are during the research process, (3) the effects of partial automation, and (4) labor allocation where researchers move to other areas.

Prediction

This table shows the rating for each area and factor, where higher numbers mean that the factor implies higher amenability to automation. The last rows show the weighted sum results and the average amenability to automation for safety and capabilities research areas:

| Factor (weight) | Interpretability | Alignment Theory | Scalable Oversight | AI Control | Dangerous Capability Evals | Pre-training Alg. Improvement | Post-training | Data generation | Agent scaffolding | Training efficiency |

| Task length (1.0) | 7.62 | 2.12 | 4.00 | 6.25 | 7.62 | 3.12 | 5.00 | 6.12 | 7.50 | 6.12 |

| Insight/creativity (1.5) | 4.56 | 1.50 | 5.00 | 6.06 | 7.56 | 6.12 | 6.75 | 8.86 | 7.50 | 6.23 |

| Data availability (0.2) | 4.88 | 3.00 | 2.25 | 2.00 | 4.12 | 7.75 | 7.00 | 6.38 | 5.88 | 7.00 |

| Feedback quality (2.5) | 3.88 | 1.38 | 3.88 | 4.38 | 3.62 | 7.50 | 7.38 | 6.00 | 7.50 | 9.12 |

| Compute vs labour (2.5) | 7.88 | 10.00 | 6.75 | 8.12 | 7.62 | 2.12 | 4.38 | 3.88 | 6.62 | 5.25 |

| Scheming risk (0.4) | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9.00 | 7.00 | 9.00 | 9.00 | 9.00 |

| Economic incentive (0.5) | 3.88 | 1.88 | 4.00 | 4.62 | 5.38 | 9.38 | 9.38 | 9.00 | 8.75 | 9.12 |

| Amenable to Automation | 5.53 | 4.04 | 4.76 | 5.78 | 5.93 | 5.37 | 6.21 | 6.22 | 7.35 | 7.09 |

| Category Average | 5.21 | 6.45 |

Overall, capabilities research seems more amenable to speedups from automation than safety research under this model. The only exception is algorithmic improvement in pre-training, because it is heavily bottlenecked by compute.

Agent Scaffolding and Training Efficiency appear to be most likely to see speedups from automation. Both have easy-to-verify progress, are not hugely bottlenecked by compute, and promise large economic benefits for AI companies. Among safety research, I believe that AI Control and Dangerous Capability Evals are more likely to see speedups from AI R&D, as they are somewhat engineering-heavy and companies have some interest in making progress on them. Alignment Theory seems least likely to see large speedups from AI research soon, mostly because it is very difficult to verify whether one is making progress and because it is largely driven by insight instead of engineering work.

The factors that most favor automation of capability over safety research are scheming risk, economic incentive, feedback quality, data availability, and reliance on engineering. Task length is neutral, while safety research is less compute-bottlenecked.

You can read my reasoning for my judgments in this Google Doc. If you think I’m wrong about something, you have 2 great options:

Put in your own numbers into an interactive version of this model

Let me know in the comments. Esp if you have experience with these areas, I’m happy to update my numbers.

Levers for affecting the order

What could we do to affect when and how much AI R&D affects capabilities and safety progress? Here we are aiming for differential acceleration, i.e., either speeding up the automation and resulting progress of safety research or slowing down capabilities research.

Slowing down the automation-based acceleration of capabilities progress might be achieved through government pressure/regulation or convincing AI companies to be careful. Additionally, it could be beneficial to give differential access to new model capabilities to safety researchers. For example, after a company develops a new model, it could first apply the model to safety research for 1 month before using it to improve capabilities. Similarly, it would be great to get commitments from AI Companies to spend x% of their compute on automated safety research.

Speeding up Safety Automation

Speeding up Safety research seems more tractable to me, as many interventions can be done unilaterally by outside actors. However, multiple of these interventions risk spillover effects by accidentally speeding up automation of capability research.

Do the schlepp of building safety research automations. There are many mundane tasks and iterations that need to be done to make automated AI Safety Research work. For example, Skinkle et al suggest making safety-relevant libraries and datasets more accessible to AI Agents. Hobbhahn argues for building research pipelines now, into which new models can be plugged. In general, people should be trying to automate large parts of safety research now, see what problems come up, fix them, and iterate on that basis. This should be a priority of safety researchers inside labs and presents an opportunity for outside startups to build safety automation tools.

Improve feedback quality. My model suggests that feedback quality is where safety lags furthest behind capabilities research. Thus, AI Safety Researchers should try to turn more safety problems into “numbers-go-up” science. For example, researchers should prioritize developing model organisms of misalignment, creating new experimental protocols for evaluating scalable oversight methods, and building simulated environments for AI control red-blue games.

Prepare research proposals. Writing up detailed research proposals and project specifications reduces the amount of novel insight needed, making it easier for AI systems to contribute. Human researchers should consider focusing their time on conceptual thinking, insight generation, and threat modelling—the tasks that are hardest to automate—while deferring engineering-heavy implementation work that AI will soon handle well.

Accelerate adoption of AI tools. Safety researchers should be early and heavy adopters of AI automation tools. This could be supported through workshops on research automation and public discussion of best practices. Golfhaber & Hoogland argue that adoption does not only mean individuals being able to automate some tasks, but that organisations adopt practices and change workflows that allow them to build so-called “automated research fleets”. Thus, it is also on the leadership of AI Safety orgs to encourage adoption by their staff and to develop the organisational structure to be amenable to AI automation.

Reduce scheming risk. Investing in AI Control and alignment research helps reduce both the probability and impact of scheming on our ability to get useful safety research out of AI systems. This is important because scheming risk disproportionately affects safety research. Funders and researchers should continue to prioritize this threat model.

Differentially accelerate helpful capabilities. Some AI capabilities may disproportionately benefit safety research. We should aim to accelerate those. Examples include conceptual and philosophical thinking, forecasting, and threat modelling. For this, a researcher should study which capabilities might be good candidates for differential automation. Then, AI Developers should prioritize improving those capabilities.

Safety Research Automation Benchmark. To make it easier to measure progress on safety research automation, Skinkle et al suggest building dedicated benchmarks, including relevant tasks. This could be a great project for AIS researchers outside of companies.

Invest in documentation. There is less public data on safety research than on capabilities research. Any AI Safety Researcher could help by releasing internal notes and failed experiments, documenting and publishing research processes (not just results), and recording and transcribing their brainstorming sessions. AIs could be trained on this data to be better able to conduct safety research, or the data could be used as additional context. Funders could also incentivise researchers to document their research progress.

Of the proposed interventions, I am most excited about safety-conscious researchers/engineers directly trying to build tools for automated AI safety research, because it will highlight problems and enables the communicate to build on them. While there is a significant risk of also accelerating capability research, I believe it would strongly differentially accelerate safety automation.

Future Work: How could this be researched properly?

I made a start at forecasting this. I think a higher-effort, more rigorous investigation would be very useful. Specifically, later work could be much more rigorous in estimating the numbers per area & factor that feed into my model, and should use more sophisticated methodology than a weighted factor model.

A key insight from the labor automation literature is that technology displaces workers from specific tasks rather than eliminating entire jobs or occupations. Similarly, the right level of analysis for our question is to look at specific tasks that researchers do and see how amenable they are to AI automation or support.

One approach for identifying the tasks is to conduct Interviews with ML Experts in different areas to elicit:

Task decomposition: Figure out which tasks they do day-to-day: “Walk me through a day in your last week.” “What concrete tasks make up their work?” “What percentage of time goes to different kinds of tasks?”

Task characteristics: For each task type, how would they rate it on criteria like: task length, feedback quality, insight vs engineering, ….

Automation amenability: Asking about their judgments and qualitative opinions. “Which tasks could current AI assistants help with?” “What capabilities are missing?” “What do they expect to remain hardest to automate?”

I did one pilot interview where I asked about the above. I learned it was useful to ask about specific timeframes for eliciting tasks (in the last month, in your last project), to use hypothetical comparisons (“how much faster with X tool?”), and not use abstract scales (“rate data availability from 1-10”) and to distinguish between different types of data availability.

Other work that seems useful:

Repeatedly run experiments measuring how much researchers in different areas are sped up by AI tools (similar to this METR study)

Interviewing researchers about their AI use and perceived speedup (although the METR study shows these estimates can be very wrong)

Creating prediction markets for this. I found it difficult to formalize questions with sufficiently clear resolution criteria.

Using more rigorous models to forecast speedups from AI automation. For a sketch of a more rigorous model, see this Appendix.

Thanks to Charles Whitman for feedback and Julian Schulz for being interviewed.

Great analysis of factors impacting automatability.

Looking at your numbers though, I feel like you didn’t really need this; you could have just said “I think scheming risk is by far the most important factor in automatability of research areas, therefore capabilities will come first”.EDIT Overstated, I missed the fact that scheming risk factor had lower weight than the others.I don’t agree with that conclusion for two main reasons:

There’s clearly some significant probability that the AIs aren’t scheming; I would guess that even MIRI folks don’t particularly expect that human-level AIs will be scheming (I’d guess that their take would be “they might be, they might not be, who knows”). So at the very least it seems like you should have a bimodal expectation, with both significant probability that alignment will be on par with capabilities, and significant probability that capabilities will come first.

Task length is also a huge differentiator and will be a much bigger deal for capabilities than for alignment. Currently for capabilities you can just look at how the AI performs on tasks that take minutes, or perhaps hours. But in the future the AIs will ace tasks that take hours, but fail at tasks that take months. That’s a really rough regime in which to do research. But many areas of alignment research would still be able to work in settings where the tasks take minutes / hours. (Put another way, I disagree with your numbers on task length, once we’re talking about AIs much more advanced than the ones we have today, which are the ones relevant for automated research.) EDIT: Perhaps I shouldn’t say “task length” specifically, see comment later for clarification.

Thanks for the input!

On Scheming: I actually don’t think scheming risk is the most important factor. Even removing it completely doesn’t change my final conclusion. I agree that a bimodal distribution with scheming/non-scheming would be appropriate for a more sophisticated model. I just ended up lowering the weight I assign to the scheming factor (by half) to take into account that I am not sure whether scheming will/won’t be an issue.

In my analysis, the ability to get good feedback signals/success criteria is the factor that moves me the most to thinking that capabilities get sped up before safety.

On Task length: You have more visibility into this, so I’m happy to defer. But I’d love to hear more about why you think tasks in capabilities research have longer task lengths. Is it because you have to run large evals or do pre-training runs? Do you think this argument applies to all areas of capabilities research?

Oh sorry, I missed the weights on the factors, and thought you were taking an unweighted average.

All tasks in capabilities are ultimately trying to optimize the capability-cost frontier, which usually benefits from measuring capability.

If you have an AI that will do well at most tasks you give it that take (say) a week, then you have the problem that the naive way of evaluating the AI (run it on some difficult tasks and see how well it does) now takes a very long time to give you useful signal. So you now have two options:

Just run the naive evaluation and put in a lot of effort to make it faster.

Find some cheap proxy for capability that is easy to evaluate, and use that to drive your progress.

This doesn’t apply for training / inference efficiency (since you hold the AI and thus capabilities constant, so you don’t need to measure capability). And there is already a good proxy for pretraining improvements, namely perplexity. But for all the other areas, this is going to increasingly be a problem that they will need to solve.

On reflection this is probably not best captured in your “task length” criterion, but rather the “feedback quality / verifiability” criterion.

Is this just a statement that there is more low-hanging fruit in safety research? I.e., you can in some sense learn an equal amount from a two-minute rollout for both capabilities and safety, but capabilities researchers have already learned most of what was possible and safety researchers haven’t exhausted everything yet.

Or is this a stronger claim that safety work is inherently a more short-time horizon thing?

It is more like this stronger claim.

I might not use “inherently” here. A core safety question is whether an AI system is behaving well because it is aligned, or because it is pursuing convergent instrumental subgoals until it can takeover. The “natural” test is to run the AI until it has enough power to easily take over, at which point you observe whether it takes over, which is extremely long-horizon. But obviously this was never an option for safety anyway, and many of the proxies that we think about are more short horizon.

For what it’s worth, I think pre-training alone is probably enough to get us to about 1-3 month time horizons based on a 7 month doubling time, but pre-training data will start to run out in the early 2030s, meaning that you no longer (in the absence of other benchmarks) have very good general proxies of capabilities improvements.

The real issue isn’t the difference between hours and months long tasks, but the difference between months long tasks and century long tasks, which Steve Newman describes well here.

I’m curating this post.

I think it’s a great example of reasoning transparency on an important topic. Specifically, I really like how Jan has shared his model in ~enough detail for a reader to replicate the investigation for themselves. I’d like to see readers engaging with the argument (and so it seems would Jan).

I also think this post is pretty criminally underrated, and part of the purpose of curation is surfacing great content which deserves more readers.

This is great.

Thinking through my own area of Data Generation and why I would put it earlier than you, I wonder if there should be an additional factor like “Importance of quantity over quality.”

For example, my sense is that having a bunch of mediocre ideas about how to improve pretraining is probably not very useful to capabilities researchers. But having a bunch of trajectories where an attacker inserts a back door is pretty useful to control research, even if these trajectories are all things that would only fool amateurs and not experts. And if you are doing some sample inefficient technique, you might benefit from having absolutely huge amounts of this relatively mediocre data—a thing even relatively mediocre models could help with.

I quite like the “Importance of quantity over quality” factor and hadn’t thought of this before! It’s slightly entangled with verifiability (if you can cheaply assess whether something is good, then it’s fine to have a large quantity of attempts even if many are bad). But I think quantity vs quality also matters beyond that. I’ll add it as a possible additional factor in the post.

I agree that this factor advantages Data Generation and AI Control. I think Dangerous Capability Evals also benefits from quantity a lot.

The biggest factors seem to me to be feedback quality/good metrics and AI developer incentives to race

In my view, funding for AI capabilities currently outpaces that for AI safety. Investors appear driven to maximise the utility of AI automation in research early on, fearing that safety protocols might eventually impede or bottleneck the pace of innovation.