Democratizing the workplace as a cause area

Introduction

It is an EA proverb that people spend 80,000 hours of their life at work.[1] That’s a lot of time where people could be happy and inventive, or miserable and unproductive. However, sixty percent of people reported being emotionally detached at work and 19% as being miserable. Only 33% reported feeling engaged. In the U.S. specifically, 50% of workers reported feeling stressed at their jobs on a daily basis, 41% as being worried, 22% as sad, and 18% angry.[2] This is not only terrible for the workers but also for the economy, since businesses with engaged workers have 23% higher profit, while employees who are not engaged cost the world $7.8 trillion in lost productivity, equal to 11% of global GDP.[3] Therefore, interventions that improve the workplace have the potential to alleviate a lot of misery.

When society went from hierarchical political structures to more democratic ones, it resulted in the populace gaining much more rights and liberties than before.[4] Yet in our everyday workplace we work in hierarchical structures that are much more authoritarian than we would ever accept from our government. If our governments tried to implement a system where the leaders had to face as little accountability to their underlings, while gaining as much monitoring and control as managers have, we would consider it a violation of our rights. While getting a job might be voluntary, everyone needs the resources and social status that jobs provide, so most people put up with the boring and repetitive work.[5]

There is an economic incentive for owners and managers to ensure the highest possible pay for themselves while establishing the lowest possible pay for their workers. Not to mention that employees don’t get a say in who gets hired or fired, despite it having a huge effect on their lives. No wonder then that employees don’t trust their companies and 75% of employees say they quit their boss, not their job.[6]

Is there an alternative? Could we perhaps run a workplace democratically? Would that improve employee welfare? Would those firms become less productive? Has this been successfully done before? Let’s take a look at the literature.

What does it mean to run a workplace democratically?

The idea is simple: Instead of the owner of the firm deciding who manages the workers, the workers become part owner and get a say in how the firm is run. There are a couple ways this could be achieved but this post will primarily focus on one well-known example: worker cooperatives. Let’s look at what the literature indicates as the benefits of democratizing the workplace:

Less inequality within firms[7]

Less workers leaving the workplace[8] either voluntarily[9] or involuntarily[10]

Workers put in more effort[11]

Similar levels of productivity as conventional firms[12]

Similar levels of investments as conventional firms[13]

Workers report increased levels of trust[14]

Lower rates of business failure[15]

There is also evidence that worker cooperatives pay their employees more than conventional firms, but only in certain circumstances. I will return to this phenomenon later. I will not be looking at other types of cooperatives like consumer cooperatives, producer cooperatives and purchasing cooperatives. This limits the scope of the literature because while 800 million people are employed by cooperatives[16], only 100 million are employed by worker cooperatives.[17] When I use the word co-op in this post, assume I mean worker cooperative unless specified otherwise.

Do Co-ops work?

You might be asking yourself: Won’t workers stop putting in as much effort into a collectively owned enterprise since the output is shared with their colleagues, which means they only get a small proportion of the fruits of their individual labor? According to the the free-rider hypothesis, rational and self-interested agents will always have an incentive to put in less effort and be a parasite of the efforts of others.[18] The business will inevitably go under as people realize that they will gain the most from shirking their responsibilities. The economist Amartya Sen once called the people depicted in these models “rational fools”.

In the case of the free rider hypothesis, these ‘rational fools’ act based on such a narrow conception of self-interest that they don’t take into account the obviously damaging long-term consequences of their behavior, both to the firm and ultimately to themselves. Normal, reasonable people—who are different to rational economic man—are usually happy to put efforts into a collective endeavor that will deliver benefits for them in the long run, even if that means foregoing some short-term gains. Cooperation in worker democracies can be a challenge and a few people will try to free ride, but evidence illustrates this problem rarely becomes so bad it affects the performance of the workers and the firm [19]

Experiments have shown that people randomly allocated to do tasks in groups where they can elect their leaders and/or choose their pay structures are more productive than those who are led by an unelected manager who makes pay choices for them.[20] One study looked at real firms with high levels of worker ownership of shares in the company and found that workers are keener to monitor others, making them more productive than those with low or no ownership of shares and directly contradicting the free rider hypothesis.[21] It turns out there are potential benefits to giving workers control and a stake in the running of the organization they work for. This allows workers to play a key role in decision making and reorient the goals of the organization.[22]

One explanation for this phenomenon is that of “localized knowledge”. According to economist Friedrich Hayek, top-down organizers have difficulty harnessing and coordinating around local knowledge, and the policies they write that are the same across a wide range of circumstances don’t account for the “particular circumstances of time and place”.[23] (For examples of this, read Seeing Like a State by political scientist James Scott) Those who make the top-down policies in a traditional company are different to those who have to follow them. In addition, those who manage the company are most often different to those who own the company. These groups have different incentives and accumulate different knowledge. This means that co-ops have two main advantages:

Workers can harness their collective knowledge to make running the firm more effective.

Workers can use their voting power to ensure the organization is more aligned with their values.

Interestingly enough, I have yet to come across a co-op that uses the state of the art of social choice theory, so they could potentially get a lot lot better.

Potential problems with Co-ops

One potential problem with the literature on co-ops is that it might be suffering from selection bias. In other words, they might not accurately represent the attributes of co-ops in general because the sample size is so small. For example: some sectors have more co-ops than others. One study found that co-ops have a better survival rate than conventional firms in the service sector, but the same in other sectors.[24] Co-ops may disproportionally start in sectors where they are more likely to succeed.[25] and people who start co-ops tend to be more motivated than the average worker.[26]

It might be that if we force people to change their firm to a co-op they are less motivated to make it work. We should probably focus on making it easier for people to transition to- or start a new- co-op voluntarily.

One issue that arises with starting a co-op is acquiring initial investing.[27] This is probably because co-ops want to maximize income (wages), not profits. They pursue the interests of their members rather than investors and may sometimes opt to increase wages instead of profits. Conventional firms on the other hand are explicitly investor owned so investor interests will take priority.

Many co-ops opt instead to rely on member contributions, which can be thousands of dollars. Economist and content-creator Unlearning economics describes the problem that arises:

If co-ops are set up in lower income communities they may have trouble obtaining financing, but if they exclude these communities then they’re going to be a bit of a middle class thing excluding the people who arguably need them most.

The most obvious policy to help co-ops finance themselves would be direct grants and loans from local and national governments, as well as other financial incentives such as tax breaks, which play a big role in Uruguay. Not only could these be expanded, but the information about how to access them could be more widespread as currently what’s available isn’t always taken up. One example is the under-utilised Local Enterprise Assistance Fund or ‘LEAF’ in the USA, which offers credit to co-ops but gets few applications, even fewer of which are credible.There are also a number of innovative ways people have got around the financing problem without direct state support. One option is to allow external shareholders who receive dividends but have partial or no voting rights, keeping the control in the hands of the workers. The successful US co-op Equal Exchange has provided these so-called Class B shareholders with annual dividends for more than 20 years. (The Class A Shareholders are the workers). In some cases financial institutions are also established as part of a concerted effort by a community to establish a democratic economy.[28]

Another avenue would be to get funding from credit unions, which are consumer co-ops. Having an economy with different types of co-ops could become crucial in making sure it can sustain itself longterm.[29] Co-ops tend to perform better with other co-ops around.[30] So it seems like starting a culture of co-ops is hard, but once you get co-op leagues started it becomes easy to sustain.[31] Ex-youtuber Rose Wrist made an outline of some different types of co-ops:

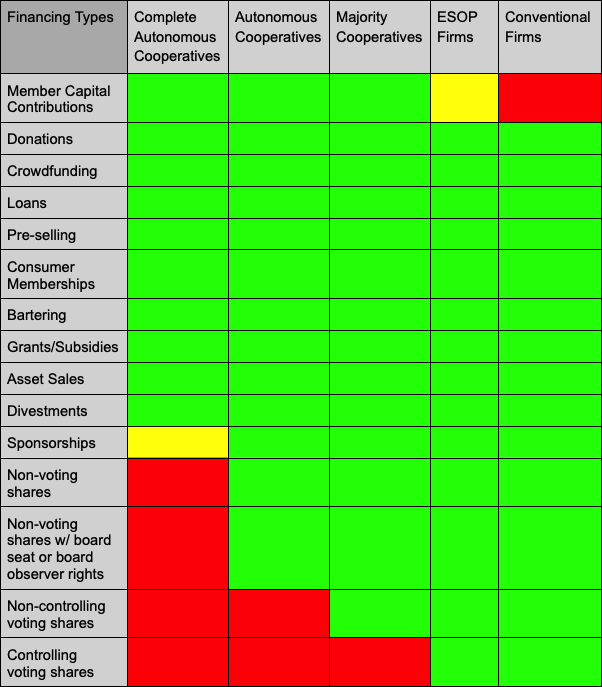

Complete Autonomous Cooperatives

These firms operate with either direct or representative democracy

These firms are completely owned by the workers at the firm

No external shareholders

Autonomous Cooperatives

These firms operate with either direct or representative democracy

These firms are majority owned by the workers at the firm

External shareholder do not hold voting shares

Majority Cooperatives

These firms operate with either direct or representative democracy

These firms are majority owned by the workers at the firm

Some external shareholders may hold non-controlling voting shares

ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership) Firms (Not a co-op)

These firms may be operated in any way

The workers at these firms all own some part of the company

External shareholders may hold controlling voting shares

He identified some unconventional ways each of these could get funding[32]:

Are Co-ops good for employees?

One problem with modern firms that I already mentioned is how disconnected employees are from their work. There’s already a great post about how important meaning is in someone’s life so I won’t go into too much detail. Suffice to say that a better working environment would alleviate this problem.

Giving employees stock in a company seems to boost their performance.[33] Research has shown that employees getting more ownership of the company is associated with higher trust, perception of fairness, information sharing and cooperation.[34] There seems to be a small increase in companywide productivity[33], while employee retention is boosted.[35] Perhaps traditional firms could slowly be eased into becoming co-ops by first giving the employees more stakes in the company and then expanding their participation rights.

While the average employee makes more in a co-op, those at the top may earn less. Similarly, switching to a co-op gives the average employee higher pay, but not those at the top. This could potentially lead to a brain drain.[7] Even if we made every firm a co-op, there would still be inequality between firms, so top earners might shift to a couple of high paying co-ops. When there is an economic downturn co-ops also tend to lower wages instead of firing people, which is once again great for the average worker but not for the top earners.[36] Volatile pay probably explains why some studies show that co-ops pay less.[37] But while getting payed less in a recession still sucks, it is preferable to getting fired. This will also have a positive effect on the family members of employees, since they also suffer when said employees are fired.[38]

Conclusion and policies

Cooperative firms are a powerful tool to improve the lives of the workforce. They reduce inequality within firms while maintaining similar (or even higher) levels of productivity as conventional firms. They improve the wage and mental health of the average worker while reducing the turnover rate. They are more resilient than conventional firms and make employees more connected with, and work harder for, their workplace.

They probably won’t slow down the rise of global inequality since inequality between firms is still possible. Co-ops may also be more risk averse since the workers livelihoods are strongly tied to the performance of the firm, which might lead to less innovation. One way co-ops can still be bad for it’s workers is if firms only hire workers for a short time and fire them before they get their vote. To prevent this governments will have to shore up their worker protection laws.

To incentivize the creation of co-ops, governments can draft legislation to make it easier (and give tax incentives) for owners to turn their firm into a co-op. The government can also give loans to employees who want to buy firms from the owners or give preferential purchasing rights for employees of a firm that is facing closure/sale. These policies are good for co-ops because they bypass the difficulty of finding initial funding. The costs to the government can be recouped by lower mental healthcare costs and reduced need for government redistribution programs (especially during economic downturns). If the literature is correct and co-ops are indeed more productive than conventional firms it could also be seen as an investment into creating an economy that generates more tax revenue.

Once more co-ops get created it will also become easier to start cooperative leagues, which aid in the creation of new co-ops. Due to vertical integration they might also be able to counteract a brain drain. More importantly, they facilitate the acquisition of equity through economies of scale which gives cooperatives more capital to fall back on. This could mitigate or eliminate the (unproven) risk aversion of co-ops.

Given the recent discussion surrounding the structuring and transparency of EA organizations, perhaps the community could consider turning their EA organizations into co-ops. Not only would this grant all the advantages mentioned in this post, it would also have two additional advantages:

It spreads the word about co-ops, making them less obscure in the collective consciousness

It would allow us to study them closely which:

Allows us to be able to draft more pointed legislation which can capitalize on their benefits while mitigating their limitations

Allows us to find ways in which they can be improved

References

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

The empirical performance of orthodox models of the firm: Conventional firms and worker cooperatives, Pencavel & Craig

New evidence on wages and employment in worker cooperatives compared with capitalist firms, Burdín & Dean

- ^

Employee Vs. Conventionally Owned and Controlled Firms: An Experimental Analysis, Frohlich et al

Workplace Democracy in the Lab, Mellizo et al - ^

Productivity, Capital and Labor in Labor-Managed and Conventional Firms, FakhFakh et al

Are Cooperatives More Productive Than Investor-Owned Firms? Cross-Industry Evidence From Portugal, Monteiro & Straume - ^

Shadow price of capital and the Furubotn–Pejovich effect: Some empirical evidence for Italian wine cooperatives, Maietta & Sena

Productivity, Capital and Labor in Labor-Managed and Conventional Firms, FakhFakh et al - ^

Do cooperative enterprises create social trust?, Sabatini et al

- ^

Survival Rate of Co-operatives in Québec, OCA

Co-op Survival Rates in Alberta, Stringham & Lee

Co-op Survival Rates in British Columbia, Murray

The Relative Survival of Worker Cooperatives and Barriers to Their Creation, Olsen

Scale, Scope and Survival: A Comparison of Cooperative and Capitalist Modes of Production, Monteiro & Stewart

- ^

Trust, Inequality and The Size of The Co-Operative Sector: Cross-Country Evidence, Jones & Kalmi

- ^

Productivity in cooperatives and worker-owned enterprises, Logue & Yates

- ^

- ^

Employee Vs. Conventionally Owned and Controlled Firms: An Experimental Analysis, Frohlich et al

- ^

Workplace Democracy in the Lab, Mellizo et al

- ^

Shared Capitalism at Work: Employee Ownership, Profit and Gain Sharing, and Broad-based Stock Options, Kruse et al

- ^

Productivity, Capital and Labor in Labor-Managed and Conventional Firms, FakhFakh et al

Quote comes from this unlearning economics video, which was the basis for this blogpost. - ^

The Use of Knowledge in Society, Hayek

- ^

- ^

Worker Cooperatives: Pathways to Scale, Abell

- ^

- ^

Survival Rate of Co-operatives in Québec, OCA

- ^

Worker Democracy, by Unlearning Economics this post could be seen as an adaptation of that video

- ^

Productivity in cooperatives and worker-owned enterprises, Logue & Yates p20

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

Employee ownership and firm performance: a meta-analysis, Boyle et al

- ^

Do Broad-based Employee Ownership, Profit Sharing and Stock Options Help the Best Firms Do Even Better?, Blasi et al

- ^

- ^

New evidence on wages and employment in worker cooperatives compared with capitalist firms, Burdín & Dean

- ^

What do we really know about worker co-operatives?, Pérotin

- ^

COVID-19-related financial strain and adolescent mental health, Stirling T. Argabrigh et al

Afterword

Some of you probably noticed that I didn’t use the word “socialist firm” or “capitalist firm” in this post. In my experience, EA’s can be quite negative towards socialism, so I thought it best to avoid the word lest I lose my karma. (If you disagree with my assessment, or need some examples before you believe me, feel free to message me). I don’t even blame the capitalists on this forum, it’s the karma-systems fault.

Since there was an initial majority of capitalists they had an easier time accumulating voting power, while socialists were disproportionally downvoted. The same thing would have happened in reverse if the socialists had held the initial majority. To illustrate, let’s get away from the tribal mindset and show that this is not even a politics thing.

Right now this is an English speaking forum and thus non-english posters/posts have more difficulty accumulating votes. This affects the people that are attracted to the forum, which increases the initial majority. Imagine what would have happened if the initial majority were Spanish speakers. We might have had a Spain tag instead of a tag for the UK and the US, and we might have had a “Mexico policy” tag instead of only a tag for UK policy and US policy. It would probably have been a Spanish language forum with more references to Latin-American culture. The forum doesn’t become Spanish because Spanish is a more rational language than English, it becomes Spanish because Spanish speakers get more votes on their posts which gives them more voting power which creates a feedback loop. (And that’s without getting in-group biases involved)

If we want to counteract groupthink I propose we make the karma system more democratic. After all, isn’t this forum kind of a workplace?

- 's comment on The Effective Altruist Case for Using Genetic Enhancement to End Poverty by (28 Oct 2023 23:45 UTC; 107 points)

- What specific changes should we as a community make to the effective altruism community? [Stage 1] by (5 Dec 2022 9:04 UTC; 58 points)

- 's comment on Doing EA Better by (18 Jan 2023 14:44 UTC; 33 points)

- The Effective Altruism community inherits the problems of the economics profession by (13 Aug 2025 14:16 UTC; 21 points)

- 's comment on Sharing Information About Nonlinear by (9 Sep 2023 11:06 UTC; 12 points)

- 's comment on Against the Guardian’s hit piece on Manifest by (24 Jun 2024 13:07 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on “Capitalism”: talking past each other by (22 Apr 2024 15:34 UTC; 4 points)

An employee-owned firm seems to be basically equivalent to a firm that gives employees shares (common) and then indefinitely prevents them from selling them (rare). The latter step seems pretty harmful to the employees; they could always keep the shares if they wanted to, but the ability to sell is quite valuable. It allows them to diversify their portfolio, rather than having their savings and job tied up in the same firm. It also allows them to liquidate the shares to fund a large purchase (e.g. a house) if they wanted to. Given how desirable these things are, I’d be surprised if banning employees from selling their shares was net beneficial to them, and without the restriction the shares they sold would typically be to third party investors, so you would naturally end up with a traditional firm again. Similarly, employees at many public companies could, if they wanted to, buy stock in their employer—e.g. a firm with 10% margins, 20x PE, paying 30% of revenue as wages, could be entirely bought out by the employees in a few years… but wisely they chose not to do so!

You correctly identify the fact that coops struggle to raise capital for investment, but I think the solutions you suggest are sort of ‘cheating’. It’s true that, if a firm only has to pay workers and suppliers because the government is covering the capital, then it will probably be able to pay those groups more than a traditional firm that has to split its revenue three ways between workers, suppliers and capital. But the traditional firm, if it received similar sized subsidies (e.g. an exemption from payroll and sales taxes) would also pay workers more and lower prices for customers. When deciding on which form of economic organization is superior for the economy as a whole, we cannot fairly compare one which needs external support to one which is self-funding.

Finally, I roll to disbelieve on the idea that coops are more productive than traditionally organized firms. There is a reason these coops have over time been out-competed by normal firms, and have become smaller as a percentage of the economy. I haven’t read all the research you referred to, but I think a common problem is the mis-identification of comparison firms. Because traditional profit-orientated firms will re-invest and expand so long as marginal product is positive, their average productivity can look lower than that of firms whose growth has been artificially constrained by the coop structure, even though this growth is in fact a good thing!

A practical example of the failure of coops comes from the ACA/Obamacare insurance coops. These received generous funding from the federal government. However, despite the advantages they had over the for-profit (and tax paying) regular insurance companies, they almost all failed within a few years due to incompetence at underwriting. They often had to be rescued by the for-profit firms to prevent leaving people without health insurance.

While theoretically poor people can buy stocks, in practice we see that it’s mostly rich people having them, co-ops would change that. Some co-ops allow workers to sell their shares, but importantly, none allow them to sell their voting shares. This distinction is important, because a co-op is not “basically equivalent to a firm that gives employees shares and then indefinitely prevents them from selling them”, it gives them shares and control. This control does allow the employees to actually sell non-voting shares if they want to (see table in the post). The difference is that they control the amount of stock in circulation. So a lot of conventional firms give their employees stock, but even if they aren’t pulling contract shenanigans, the owners still control the amount of stock that is sold. They very rarely give their employees preferred stock and they can dilute the value of employee stock at any time without their input. This is impossible in a co-op.

But the control aspect is not only important to protect the workers, it actually makes the firms perform better. Let’s take a look at source [9]: Do Broad-based Employee Ownership, Profit Sharing and Stock Options Help the Best Firms Do Even Better?, Blasi et al. They looked at firms in the USA, some of which had what they called ‘shared capitalism’ which includes stock options and other profit sharing practices. The study looks at the relationship of shared capitalism to outcomes like profitability and the likelihood employees will leave. Interestingly enough, they investigate how these things are affected by the combination of ownership and participation:

On the y-axis we have voluntary turnover, which we ideally want to be low. On the x-axis we have a measure of how empowered employees are (using the index of trust, participation, and information sharing constructed by the authors of the study). The red line shows the effect of employee empowerment on voluntary turnover for firms with no shared capitalism. The black line shows the same for firms with a high degree of shared capitalism. For the firms without shared capitalism, greater empowerment has no effect on workers’ likelihood of leaving, as shown by the flatness of the red line. Perhaps this is because workers do not value greater responsibilities without ownership. But for the firms with shared capitalism, greater empowerment is associated with lower voluntary turnover, as shown by the downward slope of the black line. All the while it doesn’t negatively affect the return on equity. In other words, under shared capitalism people are less likely to leave when they are given a bigger role in the firm’s decisions. It seems the combination of ownership through shared capitalism and of control through empowerment produces lower turnover rates than either one on their own. Merely owning stock is not enough; you have to be able to take part in the running of the organization to make the ownership meaningful.

They struggle to raise initial investing[27], but after that they actually become more resilient than conventional firms and don’t need “constant government intervention”[15][13]. That’s why I advised to make it easier to turn existing firms into conventional firms, that would remove the initial hurdle. It’s interesting that you chose sales taxes and payroll taxes, both of which are regressive taxes that I would be in favor of abolishing anyway (although I would be okay with a sales tax on things like yachts). Even if the payroll taxes fall on the employer, they can just pass it off to employees in the form of lower wages. With other taxes (like LVT) you can’t pass it on to the populace. In practice we observe that employers don’t spend more money on wages when they make more profits, but instead invest them in stock buybacks. This makes investors richer while worker wages stagnate, despite workers becoming more productive. This is one of the main reasons inequality is rising.

They are not outcompeted everywhere. In places where there are already lots of co-ops (like France, Uruguay and Italy) co-ops are very competitive. Capitalist firms do better when there are more capitalist firms around, co-ops do better with more co-ops around.[30] Also, just because a firm is more productive doesn’t mean it’s more competitive in a capitalist system. Capitalists favor capitalist firms (obviously): if a startup co-op can turn $10 of investment into $1000, but will split that $500 with the workers and $500 with investors, while a capitalist startup can turn $10 into $900 that goes purely to the investors, of course the investors will invest in the capitalists startup even though it’s less productive. And yes, the scientific literature does show that co-ops are at least as, if not more productive than capitalist firms.[17][33](this one is a meta-analysis, not just a study) The reason I put similar levels of productivity in my post, is that the increase in productivity, although significant, is small, and I want to make conservative claims.

They are consumer co-ops, not worker co-ops. Different type of co-op.

This is a fantastic idea! It’s very unfortunate to see the reaction in the comments is so negative and skeptical—though many of those who agree with you may have simply not bothered to comment.

I can actually imagine this cause area gaining broader approval in the effective altruism movement, if only influential effective altruists brought up the topic. I find it somewhat surprising to see that other progressive political change (prison reform, immigration reform, animal advocacy in politics) is somewhat broadly supported in the effective altruism movement, but workplace democracy seemingly isn’t (yet!). It does seem like the effective altruism movement will have to become more democratic before we may see that happen. Let’s hope that this situation will one day change.

Apologies if I misunderstood your argument.

You open your argument with saying, in essence, that people hate their jobs and are miserable at their jobs.

You then argue that socialist firms are better for employees.

The logical inference here would be that socialist firms make for happier employees.

Is this a reasonable summary?

However, in the “Are socialist firms good for employees?” section, you do not give much evidence that workers in socialist firms are significantly happier. Instead, the paragraph says things like:

These things, while maybe valuable, does not give that much overall evidence for life satisfaction or happiness.

Overall I am not sold that your argument-as-stated is sound, even if every individual piece of evidence is true (which is of course unlikely).

The mental health aspect is important, but also, don’t forget the potential impact of economic growth: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/bsE5t6qhGC65fEpzN/growth-and-the-case-against-randomista-development

I wanted to give a brief summary of the literature so as to not make the post too drawn-out. But I’ll go over it in more detail:

I mentioned that source [14] found that co-ops create more social trust. But what did they find exactly? Sabatini et al investigated the role of cooperative enterprise in the creation of social trust in Italy. They find that, unlike any other type of enterprise, cooperatives have a particular ability to foster the development of social trust. This supports the view that the development of cooperative enterprises—and, more generally, of less hierarchical models of governance and of enterprises that do not aim purely to maximize profit—may play a crucial role in the diffusion of trust and in the accumulation of social capital. Trust reduces uncertainty and transaction costs, enforces contracts, and facilitates credit at the level of individual investors, thereby enhancing the efficiency of exchanges and encouraging investment in ideas, human capital and physical capital.

Now this study isn’t perfect. The cross sectional design of the survey has prevented it from controlling for fixed effects at the individual level. In addition, it did not carry out fully randomized experiments, and it has not been able to isolate suitable instrumental variables. Hence, it cannot exclude the existence of some form of endogeneity leading to inconsistent estimates. Still, this is the best study we have so even if it’s not 100% certain, it’s already very promising.

In the post I summarized the work of Blasi et al as:

How they researched this is by studying the effect of employee ownership on company culture and function. The analysis of the data set finds that shared ownership forms of pay are associated with high-trust supervision, participation in decisions, and information sharing, and with a variety of positive perceptions of company culture, plus, it’s also associated with lower voluntary turnover and higher return on equity. The random-effects estimates mainly reflect comparisons between firms rather than within firms, which means it’s possible that there are unobserved firm characteristics that help account for the findings. Nevertheless, these results indicate that group incentives are likely to have positive effects if implemented in the appropriate way – with supportive HR policies rather than on their own. (Additionally these results indicate that public policy supporting group incentives, which may be motivated by a concern to increase middle class incomes and share the rewards of economic performance more broadly, is unlikely to harm and may even improve economic performance.)

I don’t consider source [31] to be strong evidence, so maybe skip this section if you’re short on time. Joshi (not Yoshi) et al. investigated 2 major cooperative leagues (Mondragon in Spain and La Lega in Italy) and the way they interact with other cooperatives and form economies of scale. The findings suggest that coops perform better in markets which have a pre-established cooperative league. This promotes a workforce with more cooperation and social cohesion which is linked to higher worker satisfaction.

On to [34]. Coad et al. analyzed the causal linkages between well-being, income, health problems, worries, autonomy and hours worked in the job for working German individuals from 1984-2008. Given that autonomy and hours worked are the key causal drivers, it seems that individuals first choose their career trajectory in terms of autonomy or personal freedom, then decide how much to work (intensity down this trajectory), and well-being (work satisfaction and life satisfaction) is the result of these decisions. Finding that autonomy is such an important non-pecuniary determinant of individual well-being is consistent with the predictions of self-determination theory and prompts a more prominent role for autonomy in labour economics. Individuals aiming at improving their workplace and general well-being are better off seeking out work that allows them room for self-determined action and discretion.

Source [35], Park et al, investigates the relationships between job demands and job search behaviour in regards to employee attitudes and behaviour for cooperatives in Seoul, South Korea. The findings revealed that worker cooperatives moderated the relationship between job demands and organizational commitment, in other words, while the negative relationship between job demands and organizational commitment was significant in capitalist firms, it was not maintained in worker cooperatives. A potential limitation of the present study is that individual-level variables were measured by self-reports (I personally don’t find this that severe).

Lastly, I didn’t put this source in the post, but it can be considered an additional piece of evidence:

Effects of Cooperative Membership and Participation in Decision Making on Job Satisfaction of Home Health Aides, by Daphne P. Berry examines job satisfaction and participation in decision making in three home health aide facilities with different organizational structures (worker-owned for-profit, for-profit with no participation or ownership by workers, and nonprofit). More than 600 surveys were completed by home health aides across the three facilities. The author also engaged in participant observation during training sessions and other meetings and conducted a small number of interviews with caregivers and agency management. Home health aides at the worker-owned, participative decision making organization were significantly more satisfied with their jobs. This study involved respondents from one of each type of business. I didn’t include it because it doesn’t study it across several types of organization, which would’ve allowed more focus on the effects of the structural characteristics of the organizations.

One last effect that I mentioned in the post (that we shouldn’t neglect) is the positive impact on the families of the employees when the employees are doing better.[38] I haven’t studied this aspect in depth, but I don’t think this claim is too controversial.

In your opening paragraph establishing the importance of the issue, I noticed that you didn’t compare the way people feel at work to the way they feel in other situations in life. Is work making some people miserable, or is work just another part of what some people experience as an overall miserable life?

While 50% of Americans say they are stressed at their job on a daily basis, 90% of Americans are satisfied with their personal life: https://news.gallup.com/poll/284285/new-high-americans-satisfied-personal-life.aspx

The fact that people don’t like their jobs but like their free-time corresponds well to my personal experience of talking to people and media portrayal of life in general: https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/MeanBoss

That’s getting toward an intriguing comparison, but it sounds like those two figures are from separate surveys? One can be satisfied with one’s personal life while also being “stressed” by it on a daily basis—for example, I just got back from visiting friends who have a fussy two-month-old baby, and while I suspect they’d say they were satisfied with their personal lives, they are certainly very stressed right now. Being “stressed” is not the same thing as “not liking” one’s job. Overall, I’d really like to see a direct comparison.

Only 21% of global employees report being engaged at work, and 19% are straight up miserable.

I don’t find it plausible that mantras like “living for the weekend” and “work is just a paycheck”, and social movements like “quiet quitting” and “躺平 (lying flat)” are prominent because people think of a job as stressful but rewarding, like having a baby.

But even if people were also miserable in their personal life, why would that exclude us from making their lives better in the workplace? It’s still 80,000 hours of your life (actually 90,000 hours) and improving your work life will improve your life overall.

For having a baby specifically, postpartum depression affects 10-20% of new mothers. A fair fraction experience suicidal ideation, and suicide does occur.

One reason we may see more explicit discussion of the stresses and dissatisfactions of working life is social acceptability bias, which is powerful enough that it can completely distort our common-sense perceptions of how the population at large feels.

Nothing precludes us from helping with people’s working life even if the rest of life also makes us miserable. However, I think it is good to approach this with clarity. For example, is there reason to think helping with the stressors of working life is more tractable, important, and neglected than helping with personal life stressors?

That’s an interesting hypothesis. I’d love to read a literature review if you want to write one.

Edit: Perhaps a better way to have phrased this is: postpartum depression would be a totally different cause area. I feel like dismissing a literature review on a cause area proposal because ‘an idea for a different cause area I just thought of could hypothetically be better and you should first research that before we take your cause area seriously’ is a standard we don’t hold any other proposal to. We don’t expect a proposal post for e.g. a fish farming cause area to also do research on malaria nets, nuclear risk, or anything else a commenter comes up with.

You’re the one proposing the new cause area :)

Yes, he is, so what? Does that mean he has to do all the work alone? Surely not. Bob pointed out a neglected area that should be investigated. By who? Probably by those best placed to do this within EA. Are you suggesting Bob is this person?

I do think Bob is this person. He is motivated, has looked into it the most, and has apparently higher credence in the idea than others. That doesn’t mean he has to go it alone, which is not something I suggested. You are welcome to help him out, for example.

I see my role here as doing informal peer review. Bob responded to my comment in a way that seemed rude and dismissive, or put the onus on me to commit to a literature review if I wanted to voice skepticism. That’s way out of line relative to the commenting norms on this forum. So I responded in a way that briefly pointed out why I don’t think that is a fair request.

You could forgive a man for losing motivation given the negative reaction this has received. I’m not too excited to spend this much effort on another post that will lose me karma/voting-power.

I really would like it if someone took it from here, perhaps an economist could do an impact analysis or a psychologist could look into the effect a higher average salary and a lower chance of being fired has on the families of the employees (my guess is it would be positive).

[LATE EDIT at 4 karma and −1 agreement:] The post and my comments now have positive karma thanks to Jobst’s intervention. So expressing socialist sentiment is not a guaranteed loss of karma but it’s still risky so my overall attitude remains the same.

One point that occurs to me is that firms run by senior employees are reasonably common in white-collar professions: certainly not all of them, but many doctors function under this system, and it’s practically normative for lawyers, operates in theory for university professors, and I believe to a lesser extent accountants and financiers. There is likely to be a managing partner, but that person serves with the consent of the senior partners.

A democracy to which new members must be voted in, socialized for a number of years, and buy in their own stake seems to have substantial advantages over one where everyone gets a vote the moment that they join. I also suspect that not understanding what they’re engaged in as a political experiment is helpful for reducing certain types of distractions.

With that in mind, expanding coops among the white-collar elite seems relatively practical, and elite persuasion is always a powerful tool.

Interesting post. Definitely a subject that must be studied from multiple angles, but FWIW I’ll mention the field of organzational economics.

I think I agree that democratizing workplaces is a good idea, and I think it is an interesting argument that this is potentially effective because so many people spend so much time at the workplace, nevertheless I would guess that spending or working on this does not come close to the cost-effectiveness of EA charities, though I have not done the math and would love to see someone do an initial exploration of this.

On a slightly related note: I am always a bit surprised by this (co-op, worker empowerment ect.) movement’s focus on creating more co-ops or buying increasing shares of companies. It seems to me that if worker ownership is a good thing, then I think the smart political play would be to just keep strengthening co-determination laws until co-ops and other companies are basically identical. After all, creating new laws or convincing the state or others to spend loads of money is a lot more difficult then continually pushing to incrementally change existing laws.

The mental health aspect is important, but also, don’t forget the potential impact of economic growth: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/bsE5t6qhGC65fEpzN/growth-and-the-case-against-randomista-development

I actually suggested this strategy in my post: