This is why we can’t have nice laws

Note: This post was crossposted from the Open Philanthropy Farm Animal Welfare Research Newsletter by the Forum team, with the author’s permission. The author may not see or respond to comments on this post.

How factory farmers block progress — and what we can do about it

Most people agree that farmed animals deserve better legal protections: 84% of Europeans, 61-80% of Americans, 70% of Brazilians, 51-66% of Chinese, and 52% of Indians agree with some version of that statement. Yet almost all farmed animals globally still lack even the most basic protections.

America has about five times more vegetarians than farmers — and many more omnivores who care about farm animals. Yet the farmers wield much more political power. Fully 89% of Europeans think it’s important that animals not be kept in individual cages. Yet the European Commission just implicitly sided with the 8% who don’t by shelving a proposed cage ban.

When farm animal welfare is on the ballot, it usually wins. Most recently, citizens in California and Massachusetts voted for bans on cages and crates by 63% and 78% respectively. Yet both ballot measures were only necessary because the state legislatures refused to act.

The US Congress last legislated on farm animal welfare 46 years ago — only at slaughter and only for mammals. Yet I’m not aware of a single bill in the current Congress that would regulate on-farm welfare. Instead, Congress is considering two bills to strike down state farm animal welfare laws, plus a handful of bills to hobble the alternative protein industry.

What’s going on? Why do politicians worldwide consistently fail to reflect the will of their own voters for stronger farm animal welfare laws? And how can we change that?

Milking the system

Factory farmers have an easier assignment than us: they’re mostly asking politicians to do nothing — a task many excel at. It’s much harder to pass laws than to stop them, which may be why animal advocates have had more success in blocking industry legislation, like ag-gag laws and laws to censor plant-based meat labels.

Factory farmers are also playing on their home turf. Animal welfare bills are typically referred to legislatures’ agriculture committees, where the most anti-reform politicians reside. A quarter of the European Parliament’s agriculture committee are farmers, and many of the rest represent rural areas.

But these factors are both common to all animal welfare legislation, not just laws to protect farmed animals. Yet most nations and US states have still passed anti-cruelty laws for other animals. And most of these laws go beyond protecting just cats and dogs. Organizing a fight between two chickens is punishable by up to five years in jail in the US — even as abusing two million farmed chickens is not punishable at all.

A few other factors are unique to farm animal-focused laws. They may raise food prices; EU officials recently gave that excuse for shelving proposed reforms. Farm animal cruelty is not top of mind for most voters, so politicians don’t expect to suffer repercussions for ignoring it. And factory farming can be dismissed as a far-left issue, which only Green politicians need worry about.

But this isn’t the whole story. Surveys show that most voters across the political spectrum support farm animal welfare laws. Politicians often work on issues that aren’t top of mind for most voters; Congress recently legislated to help the nation’s one million duck hunters. And politicians happily pass laws that may raise food prices to achieve other social goals, like higher minimum wages, stricter food safety standards, and farm price support schemes.

Master lobbyists, with tractors

A more potent factor is the farm lobby. They achieve impressive feats. Farmers are wealthy, but receive lavish government subsidies. They’re few, but two dozen sit in the US Congress. They’re mostly conservatives, but liberal politicians still do their bidding — see Democratic Senator John Fetterman’s new bill to crack down on egg alternatives.

How do they do it? Money helps. The US National Pork Producers Council spent $2.8M lobbying last year, much of it presumably to advance the anti-animal EATS Act. Individuals, companies, and groups associated with the meat industry made about $45M in political contributions in the 2020 election cycle — about $45M more than animal advocates.

Farmers are also well-organized in powerful lobby groups, which craftily inflate their numbers. The American Farm Bureau claims six million members, but most are insurance customers, not farmers. Europe’s Copa Cogeca says it “represents over 22 million farmers and their family members,” but that’s just the number of Europeans who work in food production.

Farmers have a hold on the popular imagination: “no farmers, no food” is a more popular bumper sticker than “no tax collectors, no government.” The Richard Scarry rule of politics warns politicians against messing with any profession which features in Scarry’s children’s books, like firefighters, doctors — and farmers.

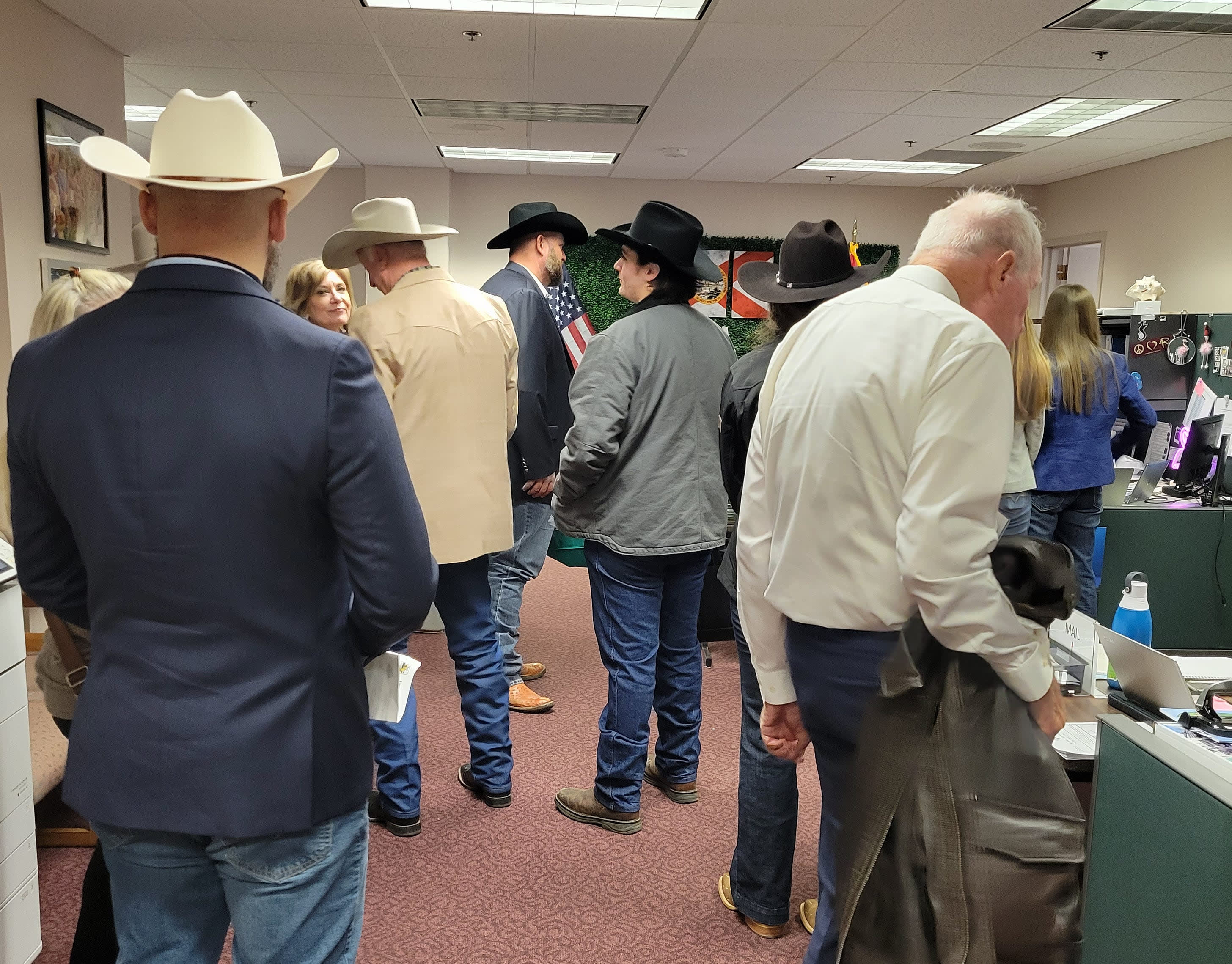

Farmers exploit this image. Whenever a bill threatens them, they show up in force — often in stetsons and spurs or John Deere caps and overalls. They proclaim themselves job creators, and threaten food shortages if they’re ignored. And when all else fails, they bring out the tractors, which they’re currently deploying across Europe to block traffic and political progress.

Moo-ving policy, baa-lancing strategies

Yet in spite of these mighty obstacles, advocates have sometimes prevailed. In 1957, a Congressional hearing screened an undercover investigation of cruelty to pigs at slaughter, leading future Vice President Herbert Humphrey to exclaim: “We are morally compelled, here in this hour, to try to imagine — to try to feel in our own nerves — the totality of the suffering of 100 million tortured animals.” The next year the Senate voted 72-9 to enact the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act. Asked if he’d support the bill, President Eisenhower purportedly replied, “If I went by mail, I’d think no one was interested in anything but humane slaughter.”

In 1978, Switzerland passed the world’s first ban on battery cages, via a citizens’ initiative. In the early 1990s, both Sweden and the UK banned gestation crates. In the late 1990s, the European Union partially banned gestation crates and battery cages — the latter with the support of 13 of 15 member states. And from 2002 on, US advocates passed a series of state ballot measures and laws to restrict the use of cages and crates in 14 states.

These wins suggest a few lessons. First, the value of citizens’ initiatives to bypass the factory farm lobby. All US state farm animal welfare laws to date have passed by ballot measure or the threat of one. Only half of US states and a handful of other countries allow for such measures. But advocates in Europe have effectively used non-binding initiatives at the EU and in France to advance reforms.

Second, the value of cross-party support. Every farm animal welfare law I’m aware of, globally, passed with cross-party support. That’s harder in today’s polarized political climate. But the industry still manages it: recent US federal bills to restrict alternative protein labels and sales all have bipartisan cosponsors. We should be able to too: there are many more conservative animal lovers than liberal factory farmers.

Third, the value of compromise. The US humane slaughter law won 72 Senate votes because it was initially limited to slaughterhouses selling to the government. The EU battery cage ban won 13 member states’ support because it still allowed for enriched cages. Some advocates today will only accept sweeping reforms — witness the animal groups who opposed California’s Proposition 12. History shows that when you demand all or nothing, you usually get nothing.

Fourth, the value of the inside game. Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton adopted a pledge to “protect farm animals from inhumane treatment,” after donors asked her to. If you already donate to politicians, consider asking to meet with them or their staffers to tell them how important this issue is to you. It’s a good time to do so: it’s election year in the EU, US, India, and a host of other countries, and politicians tend to listen best when they want your vote or your money.

Source: DierenCoalitie.

Fifth, the value of engaging political candidates and parties. I love the new approach of a Dutch coalition of animal groups, which asked each political party their stance on a set of farm animal welfare questions, and then compared their stance with the (much better) views of each party’s voters. You can help. Europeans can ask your MEPs to help revive the EU’s farm animal welfare reform; Americans can ask your representatives to oppose the EATS Act; everyone else can ask you politicians to support reforms.

All this is not to say we should focus primarily on legislation. Advocates have won stronger animal welfare policies from corporations than governments, in part because they’re less beholden to the factory farm lobby. Other advocates work to change our culture, diets, and technology — all are critical tasks. So eventually will be passing legislation. Our challenge is to convert the popular support we already enjoy into the legal protections that farmed animals deserve.

Thank you so much for an excellent post.

I just wanted to pick up on one of your suggested lessons learned that, at least in my mind, doesn’t follow directly from the evidence you have provided.

You say:

To me, there are two very opposing ways you could take this. Animal-ag industry is benefiting from cross party support so:

A] Animal rights activists need to work more with the political right so that we get cross-party support too, essentially depoliticising animal rights policy, with the aim of animal activists also getting the benefits of cross party support.

B] Animal rights activists need to work more with the political left so that supporting animal farming is an unpalatable opinion or action for anyone on the left to hold, essentially politicising animal rights policy, with the aim of industry loosing the benefits of cross-party support.

Why do you suggest strategy A] depolticisation? Working with conservative animal lovers. Do you have any evidence this is the correct lesson to draw?

I have not yet done much analysis of this question but my initial sense from the history of social change in the US is that the path to major change though an issue becoming highly politicised and championed by one half of the political spectrum is likely to be the quicker (albeit less stable) route to success, and in some cases where entrenched interests are very strong, might be the only path to success (e.g. with slavery). I worry the a focus on depoliticsiation could be a strategic blunder. I have been pondering this for a while and am keen to understand what research, evidence and reasoning there is for keeping animal rights depoliticsed.

Thanks, this is a good point. I agree that it’s not obvious we should choose A) over B).

My evidence for A) is that it seems to be the approach that worked in every case where farm animal welfare laws have passed so far. Whereas I’ve seen a lot of attempts at B), but never seen it succeed. I also think A) really limits your opportunities, since you can only pass reforms when liberals hold all key levers of power (e.g. in the US, you need Democrats to control the House, Senate, and Presidency) and they agree to prioritize your issue.

My sense is that most historic social reforms also followed path A), e.g. women’s suffrage, child labor, civil rights. In the UK, cross-party support was also critical to abolishing slavery, while in the US, where abolition was more politicized, it took a Civil War.

That said, the farm animal welfare successes of A) mostly occurred in past decades when politics was less polarized and I think some modern movements like climate change suggest A) may be the only plausible path today. I also wonder if we might be able to do some of A) and B). E.g. try to make being pro-factory farming an unpalatable opinion for anyone on the left or moderate right to hold—leaving just the most conservative rural representatives championing it.

As a non-expert, this is surprising to me. And I’m not sure that this applies to the US context. I think it’s useful to distinguish between party polarization (democrats vs republicans) and ideological polarization (liberals vs conservatives). Almost any reform passed in the 1950s-1970s probably had bipartisan support, since the two parties were hardly ideologically polarized at that time. But many of these reforms were absolutely politicized on ideological grounds (liberals typically were in favor of civil rights and environmental reforms. Conservatives were not). I think the anti-slavery movement fits this description as well. Until the last few years before the civil war, the two major political parties (democrats and whigs) both contained large groups of pro-slavery and anti-slavery politicians. So opposition to slavery was bipartisan even though it was clearly polarized on ideological and geographical grounds. Only in the few years before the civil war did the major parties become polarized on the slavery issue.

In recent decades, since the two major parties have become more ideologically polarized, it seems like major reforms were politicized on both party and ideological lines (LGBTQ rights and climate change come to mind).

So, my guess is that most major social reforms in US history were highly politicized on ideological lines, but not necessarily on party lines. I could be wrong though. This is mostly based on reading wikipedia pages.

Yeah that’s a great point. I think you’re right that these issues were ideologically polarized historically, and that now the parties reflect that polarization, it may mean that most social reforms will be politically polarized too.

Thank you for a nuanced and interesting reply.

I can’t speak for Lewis but as an animal advocate running an organisation, my bigger concern is that politicisation is irreversible and destroys option value.

I think you’re asking a general question of whether we should politicise or depoliticise issues we care about. I pretty much always think the answer is depoliticise, because very crudely, I expect the right and left to be in power about 50% of the time in 50% of the places, so if we want the laws we want everywhere, we should depoliticise things we care about.

Thank you for your detailed, well-informed, and clearly written post.

This probably doesn’t address your core points, but the most plausible explanation for me is that vegetarians on average just care a lot less about animal welfare than farmers care about their livelihoods. Most people have many moral goals in their minds that compete with other moral goals as well as more mundane concerns (which by revealed preferences they usually care about more), while plausibly someone’s job is in top 1-3 of their priorities.

Sure there are some animal advocates (including on this forum!) who care about animals being tortured more than even farmers care about their jobs. But they’re the exception rather than the rule; I’d be very very surprised if they are anywhere close to 20% of vegetarians.

There are also plenty of people whose economic or other interests are indirectly affected by agricultural interests. If you live in an agriculture-heavy district, anything that has a material negative effect on your community’s economics will indirectly affect you. That may be through a reduction in the amount consumers have to spend in your local area, local tax revenue, farm job loss increasing competition for non-farm jobs, etc.

Yeah good point. I think welfare reforms should mostly be good for these indirect players, since the reforms mostly require agribusinesses to invest more in new infrastructure (e.g. building more barns to give animals more space) and increase staffing (e.g. cage-free farms require more workers than caged farms). But I agree that the indirect players probably don’t see it this way.

Thanks Linch. Yeah I think you’re spot on about the salience / enthusiasm gap. I should have emphasized this more in the piece.

[This is a US-focused comment; it’s been ~20 years since I took a comparative government class.]

Looking at this through the lens of incentives would suggest the task is fairly difficult due to incentives at the district and state levels, especially as they relate to logrolling.

The folks on the ag committees aren’t there because they hate animals; they generally have sought that committee assignment because ag interests are important to their constituents. In other words, it is particularly costly in political terms for these legislators to move legislation that is perceived as harming ag interests forward.

The US seems to have fewer cross-cutting cleavages than it used to. I would assume that people who care a lot about factory-farming issues, for whom a politician’s position might reasonably be expected to impact their vote, are disproportionately concentrated in large cities. They are disproportionately in the leftmost quintile of the U.S. political distribution. Meanwhile, ag-heavy districts tend to be more conservative, even when the seat is held by a Democrat. I suspect few voters most interested in animal-welfare issues are likely to vote for—or donate to—the types of politicians who currently represent ag-interested districts anyway (no matter what their votes are on animal-welfare legislation).

Therefore, there is usually little counterfactual upside (and a significant downside) for a number of critical legislators to support bills opposed by the ag industry. While money and organization play a part, I think the harder issue to address is the nature of US Congressional elections happening by district and state, and the geographic concentration of many interest groups.

Also, I focusing on the number of factory farmers would understate the ag interests in these districts. Just because someone doesn’t have kids doesn’t mean they do not factor in the importance of education for the overall welfare of their community. Likewise, one doesn’t have to be a factory farmer to realize that agricultural interests play a significant role in the economic welfare of their specific communities. So there is a wider group of people in the district who indirectly benefit from what helps ag interests.[1]

I think this also holds for a number of politicians not on the ag committees. In many cases, the margin of error for getting something through Congress is pretty low. Bipartisan cooperation is all too uncommon, and Senate rules give a minority faction significant powers to make passing legislation difficult and costly in terms of legislative resources. That means that each legislator’s individual vote can be important.

I also think that focusing on the majority’s support for reforms can understate the importance of logrolling / vote trading in legislatures. Because certain districts care a lot about ag interests, other politicians can and do appeal to those interests in logrolling trades. For example, if you’re a Democrat in a relatively conservative district/state, party leadership is going to ask you to cast some votes that are going to make your life more difficult. What is leadership going to offer you in exchange for that vote you cast on (e.g.) abortion that will irritate a decent number of the people who voted for you?

Ag issues are in a sense ideal trade objects for this kind of logrolling; they are low-cost for the rest of the party (because failure to push welfare bills is unlikely to have negative electoral consequences for anyone) but high-benefit for the receiving politician. That, of course, doesn’t mean that lobbying is futile. But I think it helps explain why it may be much less successful than polling numbers would suggest.

Of course, a given reform bill might not actually hurt the district’s broader economic interests—as opposed to those of big ag companies. But that may be a tough case to make legibly to the district’s voters.

Thanks Jason! You raise some really interesting points. I particularly like your logrolling point, which I think explains well the disproportionate power of reform opponents on ag policy. The decline of rural Democrats may be quite helpful here in getting the Democratic party onboard. But it won’t help with Republicans, where I agree that pro-reform suburban Republicans are likely going to keep trading away this issue to anti-reform rural Republicans.

I liked this post a fair bit, thank you.

> America has about five times more vegetarians than farmers — and many more omnivores who care about farm animals.

...

> How do they do it? Money helps. The US National Pork Producers Council spent $2.8M lobbying last year, much of it presumably to advance the anti-animal EATS Act. Individuals, companies, and groups associated with the meat industry made about $45M in political contributions in the 2020 election cycle — about $45M more than animal advocates.

Wait—did vegans and animal rights groups really donate approximately $0 to political donations (at least in 2020)?

The facts you present seem to imply that the public cares about this issue in surveys, but doesn’t care about it enough to actually spend much money trying to change things.

On that note, $45M really doesn’t seem like much to me, though that was just on that one election cycle. I’d hope that animal rights people could organize $100M/yr for this sort of thing. 1% of Americans identify as Vegan, if they all donated an average of $33/yr, that would be $100M/yr.

Thanks Ozzie! I should have been more precise in my claim. I’m guessing people who happen to be vegans or animal rights activists cumulatively donated millions in the 2020 election cycle. I’m just not aware of anyone donating substantial $ for the purpose of advancing animal advocacy.

But, in fairness, this may well be true of a lot of the $45M donated by industry-aligned individuals too. E.g. $14.7M of the $45M was donated by executives of Mountaire Corp, almost entirely to conservative groups. My guess is that’s likely because those executives are personally conservative—not because they’re buying influence.

And yeah I agree the money involved is surprisingly little given the stakes. I’d love to see someone try to organize vegans to give politically, though you’d also need to get the vegans to tell politicians this is why they’re donating, which might be more challenging.

Vegans could donate to an animal protection group, like HSUS, to lobby on their behalf. That should make it clear why they’re donating.

Yea, this is what I was assuming the action/alternative would be. This strategy is very tried-and-true.

Surely SBF count[s/ed] as a vegan and an animal rights guy? He alone donated over $5m to Biden.

I doubt that was to support animal protection, though.

This seems like an isolated demand for rigour. When Hormel employees and other associated people gave $500k to an end-of-life care charity—a donation which is part of Lewis’s data—I don’t think this was a secret scheme to increase beef consumption. (I’m not really sure why it’s captured in this data at all actually). People who work in agriculture aren’t some sort of evil caricature who only donate money to oppose animal protection; a lot of their donations are probably motivated by the same concerns that motivate everyone else.

Thanks for flagging that. I agree that most of the funds donated by animal ag employees were not to oppose animal protection, or likely any specific policies. I should have clarified that. I also generally don’t think of people working in agriculture as evil. I think they’re mostly just doing the rationale thing given the goal of profit maximization, and the lack of constraints we’ve imposed on how to pursue that.

Ya, I wouldn’t want to count that. I didn’t check what the data included.

I agree. I think if the money is coming through an interest/industry group or company, not just from an employee or farmer, then it’s probably usually lobbying for that interest/industry group or company or otherwise to promote the shared interests of that group. Contributions from individuals could be more motivated by political identity and other issues than just protecting or promoting whatever industry they work in.

“Moo-ving policy, baa-lancing strategies”

After some poor sleep last night, I was getting a bit tired at the halfway mark, but this helped me push through—and I’m glad I did what a fantastic summary. Like others I’m amazed how little political lobbying is done by the animal rights “lobby”

Thanks Nick! That’s very kind :)

To me, the subsidies that farmers receive is yet another example of how government taking taxpayer money and giving it to people/businesses can lead to outcomes which a majority of people don’t approve of. I hope this example makes people more likely to entertain a deontological objection to any kind of government subsidy.