My experience experimenting with a bunch of antidepressants I’d never heard of

This isn’t professional medical advice, it’s just my experience and amateur knowledge.

Summary

I got moderately (and occasionally, severely) depressed about four months into the pandemic.

I tried a bunch of things to treat it, including therapy, antidepressants, meditation, and a long list of other things.

I was prescribed the antidepressant sertraline (aka Zoloft) by my NHS GP, and it really helped! But it had a number of side effects that made me very unexcited to stay on it.

I experimented with a bunch of different types of antidepressants to see if I could find one that worked well and didn’t give me bad side effects.

I knew this would probably be a long and grueling experiment… and it was. It took over a year, and was really hard, both emotionally and physically.

But I ended up finding a great one for me, and it now feels well worth the costs.

I think this kind of experimentation might be a good approach for some people who also experience depression and anxiety.

Caveats:

This was expensive. It’s probably much harder to do this without savings or great insurance, or both.

I have a particularly supportive work environment and partner. It’s probably much harder to do this without those things.

Things besides antidepressants were also really important to feeling better (and also allowed me to stick with the experiment). Therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) were extremely effective for me in treating my imposter syndrome and perfectionism, and in making my depression manageable. Searching for an antidepressant that worked for me probably wouldn’t have gone nearly as well if I hadn’t done it alongside these other practices.

Antidepressants have not solved all of my problems — and it’s important to set reasonable expectations for how much they can help.

Context

I got moderately (and occasionally, severely) depressed about four months into the pandemic.

This was triggered by:

The pandemic — including things like: feeling very isolated, not having much personal space, shitty British weather, having to work from home, not being able to see my family for years.

Genetics — my mom has suffered from moderate-severe depression since she was in her early thirties.

Imposter syndrome at work — I’d gotten a dream job, but it felt like, sooner or later, my employer would realize I was a total phony. I was afraid to do really any task that might reveal I was actually a big idiot, which made me anxious for a lot of my day-to-day activities.

My main symptoms were:

Having continuous low mood or sadness

Feeling hopeless

Having very low self-esteem, feeling like I was letting everyone down all the time

Feeling tearful

Feeling guilt-ridden

Feeling irritable and intolerant of others

Having little motivation or interest in things — finding myself and everyone else really boring

Finding it difficult to make decisions

Not getting much enjoyment out of life, including out of things that were previously some of my favorite activities (hiking, seeing close friends)

Feeling anxious and worried

Non-pharmacological things I did to treat my depression:

Weekly therapy with an excellent therapist, who taught me a bunch about CBT (helped a lot)

Weekly therapy with a couples therapist (sometimes my depression made me especially angst-y about my relationship) (helped a bit)

Taking time off work (sometimes helped, sometimes made things a bunch worse)

My depression was a factor in switching jobs (kind of helped)

Changing my role at work significantly to focus on tasks I found especially exciting and satisfying (helped a lot)

Spending time in sunnier countries (helped a fair bit)

Regular exercise (helped a fair bit when I actually had the motivation to do it)

Meditation (unclear if it helped)

Kept a gratitude and positive-self-talk diary (maybe helped a bit)

Bright lights at my desk and indoor tanning for seasonal affective disorder (unclear if it helped)

These things helped a bit, but not enough to make a dent in my worst symptoms. I had a strong feeling that there was just some basic chemistry going wrong in my brain that was “shifting all of my experience down” — making things I used to enjoy unenjoyable, and things that used to feel kind of hard feel intolerably bad.

My GP and therapist agreed and encouraged me to try an antidepressant.

I was prescribed the antidepressant sertraline (aka Zoloft) by my NHS GP, and it really helped! But it had side effects:

Insomnia

Anorexia (especially at the beginning)

Stomach problems (really bad ones)

And what the field of psychiatry calls “sexual dysfunction”

I won’t say much about the details of these, but I will say: I didn’t take these side effects very seriously for a long time, despite the fact that they were making my day-to-day life a lot shittier in some ways. I thought: What right do I have to complain about e.g. sleeping badly, when the alternative is depression? If I went off these, I’d be sad again, which would make it hard to work — I can’t jeopardize my work just because of these.

It was hard for me to come to terms with the fact these were real and serious issues, and that it wasn’t “irresponsible” or “selfish” of me to try to treat my depression in a way that didn’t reduce my life satisfaction in other areas of my life.

When I eventually did come to terms with that, I decided to try going off sertraline. And then got very depressed again.

The idea: experimenting with a bunch of antidepressants

I explained all of this to one of my colleagues, Howie Lempel, who lots of people will know is just extremely thoughtful and wise about mental health.

Howie suggested I see a psychiatrist (rather than an NHS GP), to learn about other classes of antidepressants, and try a bunch out to find out which actually worked best.

I was very, very opposed to this idea. Going on and off antidepressants was really hard for me. When I started taking them, I had such bad side effects I had to take time off. And when I went off them, I had brain fog and “brain zaps,” both of which are really uncomfortable and frustrating. Plus, it can take up to four weeks to know if an antidepressant is working for you, so trying several takes many months.

Howie countered:

The upside potential for a person with a predisposition for depression could be huge: spending three to twelve months of my life going on and off antidepressants, while horrible, would be so incredibly worth it if I ended up finding an antidepressant that made me happier and more resilient without ruining my sleep and destroying my digestion.

The sooner I found the right antidepressant for me, the more years of Feeling Happy I would get to have over the course of my life — hopefully another 60+ years. So a huge deal, and one that I think lots of people don’t fully appreciate when deciding whether to try to address the problems in their lives now or put it off.

And reminded me I’m currently lucky enough to have very supportive employers, who would support me with both my mental health expenses and in taking time off if necessary.

And I was convinced.

So I got a psychiatrist and started learning about antidepressants.

What I learned about antidepressants

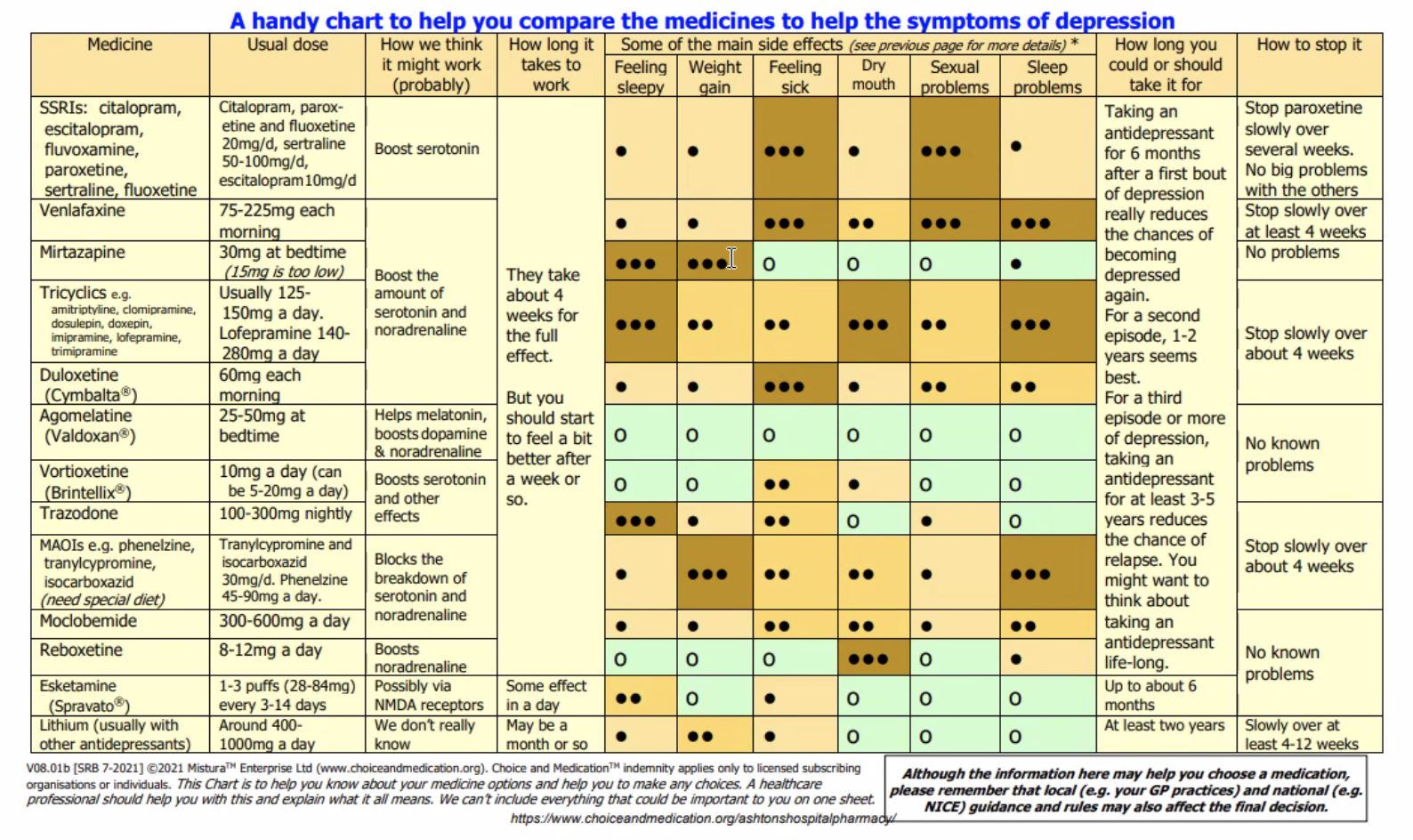

There are so many! I’d only really heard of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (and Wellbutrin aka bupropion, because of Rob Wiblin’s blog post on the topic) — but there are a bunch of other types: serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), noradrenaline and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NASSAs), tricyclics (TCAs), serotonin antagonists and reuptake inhibitors (SARIs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

And different ones seem to work for different people, and they have pretty varied side effect profiles.

It’s really hard to predict which will work for you! Very little is known about why some people respond better to some antidepressants while other people respond better to others. And while you can do genetic testing to try to get a bit of additional evidence about which antidepressants might work best, it’s not super accurate yet — plus, it’s expensive and doesn’t tell you anything about which drugs are likely to give you side effects.

But research on antidepressants can help.

I’m not going to do a full literature review here, but I wanted to highlight the meta-analysis my psychiatrist and I used to decide which antidepressants to try and in what order. Here are the headline findings from the “head-to-head studies” — which compare treatments to each other, rather than just comparing treatments to a placebo:

Effectiveness:

In head-to-head studies, agomelatine, amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and vortioxetine were more effective than other antidepressants (range of ORs [odds ratios] 1·19–1·96), whereas fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine, and trazodone were the least efficacious drugs (0·51–0·84).

Acceptability (how “acceptable” is the drug — how bad are the side effects, measured by dropout rates):

For acceptability, agomelatine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, and vortioxetine were more tolerable than other antidepressants (range of ORs 0·43–0·77), whereas amitriptyline, clomipramine, duloxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine, trazodone, and venlafaxine had the highest dropout rates (1·30–2·32). 46 (9%) of 522 trials were rated as high risk of bias, 380 (73%) trials as moderate, and 96 (18%) as low; and the certainty of evidence was moderate to very low.

The evidence for drugs with smaller sample sizes is weaker than the evidence for drugs with larger sample sizes. The size of the circles in the diagram below represent the number of randomly assigned participants in all of the studies included in the meta-analysis. The width of the lines is proportional to the number of trials comparing every pair of treatments. So those with the biggest circles and the thickest lines have the strongest evidence base.

The graph below brings these two factors (effectiveness and acceptability) together[1] — top right is good, bottom left is bad:

My experiment

Start with the SSRIs — they seem to work for lots of people, and very easy to get from a general doctor.

Then, with the help of a psychiatrist, try as many antidepressants as it takes to find one that both helps me, and doesn’t give me loads of side effects.

Start with the antidepressants with the fewest side effects.

Start with the lowest possible dose to see if I can get an effect on my depressive symptoms while reducing the chance of side effects.

With this in mind (and using the handy chart above!), my psychiatrist and I developed an ordered list of which antidepressants to try:

Sertraline (Zoloft)

Bupropion (Wellbutrin)

Fluoxetine (Prozac)

Citalopram (Celexa)

Agomelatine (Valdoxan)

Vortioxetine (Brintellix)

Reboxetine (Edronax)

Venlafaxine (Effexor)

After that… come back to the drawing board.

And we used these guidelines for switching between specific antidepressants to figure out how to transition from one to another.

The results

I tried a total of six drugs (some at several doses) over the course of a year and a half.

There were lots of ups and downs associated with going on and off these drugs:

🤢=stomach issues 🥱=insomnia 😴=sleeping hard 🤮=nausea and/or vomiting 🤪=hypomania

🤒=flu-like symptoms 😭=extreme depression and anxiety 😶🌫️=brain fog 🧠⚡=brain zaps

But overall, I was able to find an antidepressant (vortioxetine) with much more manageable side effects, and overall, I feel much happier than I was in 2020 and 2021.

I don’t feel “done” — I’m not happy all the time, and there are still emotional bumps in the road of my recovery.

There’s definitely still some room for improvement, but I’m happier than I’ve been in a long time, and I no longer score in the clinical ranges on depression. I tracked all this progress as part of the experiment, which you can see in the graph below — lower scores are better, as they indicate fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression.

The scores indicate the following severity: 0-4 none, 5-9 mild, 10-14 moderate, 15-19 moderately severe, 20-27 severe.

I measured my anxiety severity using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7).

The scores indicate the following severity: 0-4 none, 5-9 mild, 10-14 moderate, 15-21 severe.

You can open this image in a new window to read the detail.

The hardest parts of this, and what got me through

The hard parts

This sucked. It was extremely difficult to stick to this plan. Staying depressed for a long time, when it felt like I could just go back on some side-effect-y SSRI and feel somewhat normal, was terrible.

This affected my job (e.g. sometimes the side effects of going on a new antidepressant forced me to take time off work) and my relationship (e.g. I was sometimes much more emotionally turbulent than my partner was used to).

Going on and off some of these was BRUTAL: a week or two of nausea, stomach problems, insomnia, tearfulness, and depression getting WORSE rather than better. These were some of the biggest costs, and while I was experiencing them, I often felt like my approach wasn’t worth the costs.

Antidepressants have not solved all of my problems. Again, I’m not happy all the time… I still feel social anxiety, work stress, and sadness a fair bit, and I still catastrophize about things — but I’ve learned a lot of healthy ways to deal with these tendencies (more on this below).

This was expensive. I had to meet with a private psychiatrist a bunch of times (£££), and I paid for the drugs out of pocket because it was a lot faster than going through my GP — I think I wouldn’t have been able to do this if I’d been in the US. I recognize this could very well make experiments like this prohibitively expensive for lots of people. If I were to try to do it more cheaply, I’d ask to be prescribed generics (which can take longer / involve more faff), and go through a GP for the more traditional medications (SSRIs, bupropion if in the US).

What got me through

Having a therapist who knew my plan, supported it, and helped me get perspective when I lost sight of why I was subjecting myself to the plan.

An extremely supportive partner, plus supportive friends who knew about my experiment, and with whom I was very open about my symptoms and side effects.

I was lucky that my workplace was extremely supportive of me spending time, money, and energy to improve my mental health. I told my manager about my plan, and got tons of support and understanding from her throughout my experiment (e.g. she was encouraging and understanding even when going on and off different drugs made it especially hard to work normal hours).

Things besides antidepressants were really important to feeling better (and sticking with the experiment). Therapy and CBT were extremely effective for me in treating my imposter syndrome and perfectionism, and in making my depression manageable.

Writing a note to myself I could read when I felt especially down:

Remember: Until [e.g. October 25th], you might feel especially sad. But it’s not going to be this way forever. You’ll get through it and then you’ll feel as happy as you did in late September. Remember that? That was fucking great. That’s very achievable again! You’ll have it back, just gotta be patient and kind to yourself for a bit longer.

- ^

“Data are reported as ORs in comparison with reboxetine, which is the reference drug. Error bars are 95% CrIs.

Desvenlafaxine, levomilnacipran, and vilazodone were not included in the head-to-head analysis because these three antidepressants had only placebo-controlled trials.”

- EA & LW Forums Weekly Summary (17 − 23 Oct 22′) by (25 Oct 2022 2:57 UTC; 35 points)

- Towards a Self by (25 May 2024 14:55 UTC; 12 points)

- EA & LW Forums Weekly Summary (17 − 23 Oct 22′) by (LessWrong; 25 Oct 2022 2:57 UTC; 10 points)

- 's comment on Consider working more hours and taking more stimulants by (18 Dec 2022 21:49 UTC; 3 points)

Thank you for sharing this, Luisa. Your openness reminds us we’re not alone in our mental health struggles. And talking about the different medication you tried and how you experimented with them may easily help others find treatments that could greatly improve their lives.

Inspiring to see someone taking such an organised, systematic approach to their health. Inspiring also to see someone sharing their mental health struggles openly and in a constructive way.

I feel like I can’t draw many conclusions from this data because of the big risk of confounding factors (maybe an external event happened while you were on one medication and not when on another), because drugs tend to work quite differently in different people, because N=1 and because there didn’t appear to be blinding.

Anectodal evidence has its place, though. Please keep up the good work.

I strongly upvoted this comment because I think your middle paragraph is a true and necessary thing to say, and phrased in a fairly kind way (where many nearby phrasings may be substantially less kind). Given the clear cognitive distortions people may have around this and adjacent topics, being reminded of “obvious facts” can still be helpful.

Thanks for writing this, great to hear that you’re feeling better.

I’m usually a fan of self-experimentation, and the upside of finding an antidepressant with few side-effects (and that you can take a lower dose of) is definitely valuable. This seems especially true if you can stop taking it during better mental health periods, then have it in your arsenal for future use. But I still have a few doubts about this process, and I’m a little concerned that some of the premises behind your experiment need a bit more scrutiny. I hope someone with a bit more domain-specific knowledge can correct me if I’m wrong, or improve my arguments if I have a point. I’m also aware that there’s no such thing as a ‘perfect self-experiment’, and I don’t think there are obvious ways that you could have improved the experiment. But here are a few things that I’d like to hear your thoughts on:

Firstly, the depression episode was triggered by an disruptive external factor- the pandemic. This would probably invalidate any observational study held in the same period. As this external factor improved, and people could start travelling/ socialising normally, you might expect symptoms to lift naturally from mid-2021 onwards. From what you’ve mentioned here, you don’t seem to have disproved this hypothesis. I gather that depressive episodes seem to last a median of about 6 months ( see pic below), with treatment not making a huge difference for duration within the first year (some obvious caveats about selection effects here). How do you consider the possibility that you would have recovered without antidepressants?

Secondly, the process of switching between 5⁄6 antidepressants seems to be a significant confounding factor here. I don’t know how good the evidence base for the guidelines link you sent was, but it seems likely that the multiple (start, side-effects, ending, potential relapse) effects of antidepressants are significant enough to really mess up any attempts to have a ‘clean slate’ between treatments, and to therefore make it a unfair comparison. It seems possible that what you thought was a negative reaction to x medicine was actually contingent on having just tapered off y medicine and/ or experiencing a relapse. Does that seem plausible, or do you think that there was a stable enough baseline for comparisons to be valid?

Third, just a bit of concern about the downsides of the experiment. There are some long-term side-effects to antidepressants, and they seem understudied for fairly obvious reasons (most clinical studies only last for 6 months, no long-term RCTs). There seems to be a few studies that point to longer-term risks and ‘oppositional effects’ being underestimated. Unknown confounding factors and additional health risks from going on and off antidepressants would make me very concerned. Obviously, untreated depression also has a range of health risks, so I don’t want to discount the other side of the ledger, but I would definitely not be confident that I was doing something safe. How confident do you feel in your comparison of these risks? And did you feel that you had to convince yourself against (potentially irrational) fear of over-medication?

Finally, a bit unrelated, there’s a meta question that often comes to mind when I read posts about more rational/ self-experimenting approaches to health issues, which is: “How strong should our naturalistic bias/heuristic be when approaching mental health/ general health issues?” Particularly for my own health, I have a moderate bias against less ‘natural’ (obviously a very messy term, but I think it’s useful) health solutions. I often feel EAs have the opposite bias, preferring pharmacological solutions, perhaps because they can be tested with a nice clean RCT. I’m interested what level of bias you, (and forum readers), think is optimal.

As a GP myself, I would love patients like you who are evidence based and committed to treatment plans!

It is well understood depression and other mood disorders are very complex and multimodal. So trying a bunch of stuff outside medication also useful.

Also worth mentioning there is A LOT or epigenetic factors we don’t understand well and can make a big difference on effects and side effects of medications. Trial and error is usually indicated like you have done in refractory and treatment resistance experience like yours.

Well done on sharing too. Mental health is like any other chronic disease, and important to aim for ‘well managed’ rather than ‘cure’ … Because we all get down from time to time!

What Stephen said ❤️ And CONGRATS ON PERSEVERING 💪 And while I’m here, big shout-out to your partner, therapist, friends, colleagues, and especially to Rob (I was actually thinking of thanking him earlier today—I am loving bupropion right now) 🙌

Small thing:

I think you’ve missed out bupropion—OR of ~1.65 according to Figure B? (Also, all the ones you list here seem to have ORs more specifically in the range ~1.45-1.96 according to Figure B?)

Good to see that your post isn’t perfect, but I thought I’d point it out 😉

Strong upvoted, I found this very interesting and I expect that quite a few people will find it helpful.

I don’t know if it’s been posted here before, but Scott Alexander has a detailed writeup on depression treatment that people may also find useful, including information on the order he often has his patients try medications in.

Highlights from the linked writeup:

Speaking as a vortioxetine user, the main advantage for me is that it has a quite different side effect profile from other antidepressants of similar effect size and “risk level”—one which I personally prefer to SSRIs, bupropion, or mirtazapine.

Seems like esketamine with “some effect in a day”, a comparative lack of side effects, and lack of withdrawal issues might be an attractive option. I am curious why wasn’t it on your list?

Note that people in US/UK and presumably other places can buy drugs on the grey market (e.g. here) for less than standard prices. Although I wouldn’t trust these 100%, they should be fairly safe because they’re certified in other countries like India; gwern wrote about this here for modafinil and the basic analysis seems to hold for many antidepressants. The shipping times advertised are fairly long but potentially still less hassle than waiting for a doctor’s appointment for each one.

Do you know of anything equivalent for stimulants? They don’t seem to have that category, and it’s more tightly regulated, so I don’t expect a positive response here, but I ask jic. I’m worried that a future dr might not renew my 3-month prescription for whatever reason, and then I’m in shambles.

Yeah, I don’t think it’s possible for controlled substances due to the tighter regulation.

Edit (Cutting out a lot in response to Charles’ comments):

Vyvance, Adderall, and coffee can each improve mood. I’ll leave it at that.

Ok there’s been a couple comments on “don’t go to your doctor”, “drug hack”.

Above:

Also here

Basically, I’m pretty sure this is wrong/dangerous.

Lisdexamfetamine is indeed being explored to treat depression, and some anti depressants like buproprion have a very stimulant sort of flavor.

But applying these theories directly as a sign of to take stimulants is very very simplistic.

Also, there’s a clownish level of abuse of medications in US/western society (see opoids).To be gearsy, one issue is that stimulants bring you up, but then you almost always have a crash or a low phase—it’s easy to see how this low phase could be very very bad for some people. These substances also have relationships with other disorders/issues that are complicated. Also, these side effects definitely aren’t “limited to being in out of your system in 24 hours”.

I don’t have a long list of references for this or time to provide this, but you can google to explore the standard issues and side effects the stimulant drugs:

RE: This and other “anti doctor stuff”.

There’s a lot to write here, but ultimately, these comments and stuff shouldn’t be on a major internet forum, definitely not the EA forum.

The following gives one pretty good argument:

Many EAs are privileged. So for this audience, these people should just see a doctor/psychiatrist to get data points, as well as their trusted network for what works.

For the people who aren’t able to see a doctor, and are under resourced, that’s bad and unfortunate, especially since on average, they have further challenges—but on average it’s likely that taking internet forum drug advice will make things further bad, especially given coincidence of further issues.

So the above sort of is a logical case that explains why internet forum for “drug hacking” (especially for mood/stimulants/depression) is bad.

This is more complicated (someone I know has a relationship with doctors where they sort of punch through and get whatever script they want, which is exactly in spirit of the above comment; doctors, psychologists are very mixed in quality; being an outlier makes all of this worse).

It’s good to acknowledge the facts above—but unfortunately properly situating this all, without causing an “EA forum style” cascade that sort of makes it worse, is hard, in addition to time, it’s sort of, “I don’t have enough crayons” or “I can’t count that low” sort of flavor.

I agree with much of what you said and so edited my post. I do have a few points to make in the abstract though.

Although patients are prone to make mistakes such as abusing drugs, the medical establishment is sometimes majorly wrong in predictable ways, and waiting for the establishment to fix itself through the official channels can take sometimes decades. If caffeine was just discovered today, I think it would be classified as a controlled substance and restricted to certain diagnoses. (No?) If so, I think that would be a huge loss for humankind.

The philosophy of clinical psychology/psychiatry as represented in the DSM strikes me as seriously flawed. They group things into discrete categories called “disorders” and eschew continuity and multidimensionality. As math (and its offshoots) becomes more wildly known, I think this will change, but it will take time. [I’m not saying that the concept of a disorder or diagnosis should be completely abandoned, but it has limitations].

Finally, the opioid comparison strikes me as strained.

I appreciate the thoughtful consideration and I agree with you. IMO I think you are right, including your points like the medical establishment is often wrong and slow. I’m less certain, but it’s possible the DSM (and maybe a lot of physiatry) is a mess.

Yes, this should be deleted. Maybe I was trying to gesture at creating subcultures that normalize drug use inappropriately, and I was using “opioid” as an example in support of this, but this might be wrong and, if anything, supports your points equally or better.

The main difference is my concern about EA having subpopulations/subcultures with different resources.

I support the OP, but I’m worried she’s an outlier, being in a place where there is a huge amount of support, creating agency for her exploration (read the 80,000 hours CEO’s story here).

I don’t want to minimizing her journey, such personal work and progress should be encouraged and written up more, because it’s great!

But, partially because this is impractical for many, I’m worried that something will get lost in translation, or some bad views might piggy back on this e.g. normalizing low-fidelity beliefs about drug use (that are Schedule II stimulants!).

Thanks for writing this up, and sorry to hear you had to suffer through this Luisa!

Some things I recently learned about antidepressants:

To limit withdrawal effects, hyperbolic tapering (reducing by x% per week) > slow tapering (reducing by fixed amount over months) > fast tapering (fixed amount over 2-4weeks) > cold turkey. https://www.madinamerica.com/2019/03/slow-tapering-best-antidepressant-withdrawal/ In addition, there’s cross-tapering (introducing a new SSRI while tapering off an old one) that’s supposedly helpful.

Some people become permanently disabled from (stopping) antidepressants. It ranges from sexual dysfunction to 9⁄10 severity and not being able to work. The risk seems to increase with duration of taking it. I don’t know how many people experience this, but it was enough to create an All-Party Parliamentary Group in the UK for it (http://prescribeddrug.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/APPG-PDD-Survey-of-antidepressant-withdrawal-experiences.pdf). This implies a risk of 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 10,000 or something? It definitely makes me wary to recommend antidepressants to anyone, especially for an indefinite period of time.

(Note: the survey linked above has a very strong selection bias, so we can’t glean much from the actual numbers besides the fact that the phenomenon exists)

This doesn’t add much, but thank you for sharing this. I honestly believe that the world would be much better (and many people on this forum much happier) if more people did this.

Thank you so much for writing this up, Luisa! It has lots of good data and advice.

A quick thought based on what helped me when I was burning out: I’d consider working part-time for a while to see if reduced work stress helps. Work is often a massive source of stress and sometimes we need extended downtime (e.g., not just a weekend) to make progress on recovering from the damage of our past stresses. Working part-time can also give you alot of time for self-care, therapy, changing habits and so on. Eitherway, I wish you the best of luck in the future!

Thanks for sharing.

I’d be interested to hear more about how you measured effectiveness.

If I understand correctly it takes several weeks to taper on and taper off most antidepressants.

Were you operating from a baseline where your depressive symptoms were fairly consistent for many months?

If not, how did you guage effectiveness vs placebo?

Perhaps you approached these tests as mostly about finding one that didn’t have acute side-effects, and also wasn’t obviously not working?

Yea, I basically did this ^^

It was just extremely obvious to me when something was working/wasn’t, and the fact that many antidepressants I was super optimistic about didn’t work makes me think I wasn’t getting huge placebo issues.

While self-reported data is obviously a bit tricky, my sense of whether something was/wasn’t working was backed up by the data I collected.

I use Daylio to track my overall mood once a day and I have 2 years worth of data there.

I use the GAD9 and PHQ-7 to track my depression and anxiety scores once every week. I have 3 years worth of data from that.

I use perfectionism and low self esteem questionnaires to track those things once a month. Data for those for about 2 years

Thanks for sharing this- it’s very inspiring but also difficult to read because it’s not realistic for many people struggling with mental health issues.

It really captures why we (I’m speaking of Canada but I’m sure this applies to many other places) have a mental health crisis. It takes years to see a psychiatrist unless you get yourself checked into the hospital and then risk being admitted to a mental health facility against your will (which is scary to say the least). To actually have a psychiatrist support you through a process like this, as well as family members and your workplace, would almost never happen here.

I’m curious how you choose the order to try the drugs in. Vortioxetine is such a positive outlier on the “effectiveness and acceptability” chart that when I saw that I assumed you would have tried it first, or at least early/soon, but instead it was the sixth you tried. Is there some generally-applicable reason why it’d be wiser to start with the other five first?

(Note: My intuition that it made sense to start with vortioxetine based on the chart info was definitely strengthened when I saw that it’s the drug you decided to stick with, but in reality I probably shouldn’t update much at all based on your one case about which drugs it’d make sense to start with.)

Yea, good question. It’s basically because I started with NHS psychiatrists (who strongly prefer to prescribe SSRIs), and only later moved to a private psychiatrist (who recommended I start first with agomelatine because of the excellent side effect profile, given that side effects were my main complaint).

Thanks for posting this, Luisa!

Depression is a beast that can affect anyone. While I have been lucky enough to evade it, I know plenty of others who suffer from it.

It’s really cool that you kept such detailed logs of your mood, wellbeing, and side effects! Your analysis is very thorough. I hadn’t heard of “brain zaps” before! This information will no doubt be useful to others.

I truly wish you the best on your journey toward fulfilment and happiness!

How did you measure efficacy?

I tracked my mood and thought patterns in a few different ways:

I use Daylio to track my overall mood once a day and I have 2 years worth of data there.

I use the GAD9 and PHQ-7 to track my depression and anxiety scores once every week. I have 3 years worth of data from that.

I use perfectionism and low self esteem questionnaires to track those things once a month. Data for those for about 2 years

Funny how the antidepressant which ended up working for you is way higher than the others in your second figure. I’m wondering why you didn’t start with this one: the smaller sample size? Also wondering how much I should update from the fact that it ended up being the best one for you.

I am very sceptical that there is a lot you can do about depression. This post explains why.

(Edit: This was an exceptionally badly written comment, and it basically guarantees a misunderstanding. Sorry about wasting everyone’s time. It was meant to be supportive, but it was not. Small explanation here.)

There’ll always be some outrageous wretch who can outdo you in depression-or-what-have-you. You have the right to complain without needing to emphasise your “luck” so much (lucky you, at least you have tissue to wipe your tears with when your brain tries to eat itself). I can outdo most people in depression without breaking a sweat, but I know I’m not the worst, and that knowledge can make it hard to summon up the gumption to say “damn, something really needs to change”. At some point you have to realise that if people at the bottom percentile also feel uncomfortable taking their problems seriously for the same relative reasons, it’s ridiculous all the way up the chain.

While I’m sympathetic to some ideas that this comment alludes to, I’ve downvoted this comment (and your comment below).

I think the tone of this message comes across to me as unnecessarily snarky/antagonistic. I interpreted the comments about luck as the author’s acknowledgement that this kind of experimentation is not feasible for everyone, and of protective factors that the author found helpful for managing difficult parts of this experimentation. I didn’t get a sense that the author was minimising her mental health by comparing herself with people who are less well-off, which is one uncharitable interpretation of your comment.

I think I might be biased here because I would find it difficult to share a personal post like this publicly, and so perhaps have a higher standard for pushbacks that don’t address the main points of the post, but feel more like nitpicks on how these kinds of personal journeys are communicated/what the author should and shouldn’t acknowledge as helpful for them. I worry that comments like this can be (mis)interpreted as potential barriers to other people sharing posts I’d be happy to see on the forum.

RE: your medical advice comment below—I viewed the disclaimer as helpful reasoning transparency to know what her background knowledge is and how she went about investigating this. I think there are also legal reasons that including a disclaimer is useful, even if the author was confident this post was as helpful as the average mental health professional’s advice.

I also think statements like “the illusion that mental health professionals usually know what they’re doing” and “most people here can do better by trusting their own cursory research” seem too strong as standalone claims. While I agree there are doctors who are bad, and doctors who are not clearly good, it’s a few steps further to suggest that mental health professionals usually don’t know what they are doing, and that most people should do their own cursory research instead of seeking input from mental health professionals. I would have found it helpful to see justification that matched the strength of those claims, or more epistemic legibility.

For example, if it is the case that people here can benefit (on net) from input from mental health professionals, then your comment may be harmful in a similar way, by perpetuating the illusion that mental health professionals usually don’t know what they’re doing, and by nudging people towards trusting their own research instead of seeking professional help. It’s unclear from the outside that it’d be valuable to update based on what you’ve said.

(Speaking in personal capacity etc)

tl;dr: I intended to be supportive. I knew my comment could be misinterpreted, but I didn’t think the misinterpretations would do anyone harm. Although I did not expect it to be misinterpreted by Luisa. And Charles He said he read it closely and didn’t decipher my intention, so I’m kinda irrational and will try to update. On rereading it myself, I agree it was very opaque.

My comment was entirely not intended as pushback on anything. I find Luisa’s ability to put in so much conscious effort into this admirable and I appreciate it as inspiration to do the same. She did not seem like she had above-average guilt-feelings for prioritising dealing with her problems when there are always others who suffer more. But because she mentioned luck, and I’m aware that this is something many people struggle with including me, it seemed plausible just on priors that she had an inkling of it. If that’s true, then there’s an off-chance that my encouragement could help, and if it’s not, then my encouragement would fall flat and do no harm.

My tone tried to be supportive by pointing out the laughable absurdity of not feeling ok taking one’s problems seriously unless they were worse than they are. I think pointing this out is high priority, because the dynamic makes for incredibly unfortunate incentives. When people speak to me about my own problems, I often find a humoristic tone to be easier to deal with (and less painfwl) compared to when people conform to an expectation that we all need to be Awfwly Severe and tiptoe around what’s being said. Although I’m aware that my intended tone would only come across if you interpreted with a lot of charity and a justifiably high prior on “Emrik will not try to be rude to someone vulnerably talking about their own depression”.[1]

Why would I keep making comments that can’t be understood without charity? Because I believe the community and the world would be better if collectively learned to interpret with more charity. And I go by the rule “act as if we are already closer to optimal social norms than we in fact are,” because when norms are stuck in inadequate equilibria, we can’t make progress on them unless we are more people acting by this rule.

I understand what you meant hear Emrik, sorry you got down vote buried

It’s no bother, dw dw. I honestly agree it was a bad comment that invited misunderstanding.

I think there should be a lot more writing in EA forum that:

direct, brief, and not trying to win the game of politeness/EA rhetoric.

Also, assuming it’s drawing and directly communicating critical skills/experience that EAs don’t have, more writing should be lower effort and not cover every base.

This will get a lot more knowledge and people with time costs/expertise, instead of the lousy situation it is in now.

But your comment is really bad, I can’t even work out what your point is, even after close reading.

Besides the second sentence which is only half about this, every sentence is about how comparing one’s level of depression to someone who has it even worse isn’t helpful or justified. Emrik also talks about their struggles with this.

Perhaps they projected onto the post author about luck, but I’d hope people with depression feel like they can say imperfect and real things about depression without getting pilloried for getting something wrong.

Agree! The combined aggregate response to the original comment is probably the least sensitive/kind conduct I have ever seen in the EA sphere

Edit: added “combined aggregate ” for clarity

i can see how you can intrepret this comment as “the OP is putting up norms by measuring their depression and I discourage this”, in an intellectual sense, but reading the ocmment, this read is still marginal, the comment doesn’t really make the case clear.

whatever their experiences are, the writer of the comment isn’t likely writing while currently in a state of depression, and are responsible for communicating. their comment is disorganized and reads like a string of consciousness (because it probably is) and it’s self involved.

note that actually i didn’t downvote the comment by the way.

Thanks for pointing out how dense the comment was. I agree, and I should probably up my bar for how clear my comments need to be so I don’t waste people’s time like this. But two pushbacks:

It’s ok if people make comments they know most people will misinterpret, as long as the misinterpretations are harmless.

And in response to your second point above, what’s wrong with being self-involved?

Where’s the part of the post you are responding to?

I made a bad comment, but I tried to explain it in response to Bruce’s comment above. Just letting you know, not requesting that you to read it.

Wow people really downvoted it. I just ignored it, in general I don’t like to downvote people who are talking about their poor mental health 🤷♂️

I think people downvoted it because it comes across more as criticism of other people, rather than the purpose being to talk about the commenter’s own mental health

And fwiw, I disagree with saying “This isn’t professional medical advice, it’s just my experience and amateur knowledge.” Perpetuating the illusion that mental health professionals usually know what they’re doing can be harmfwl, especially in this crowd, because most people here can do better by trusting their own cursory research.

Not sure why people were using the main downvote button on this one, and not just the disagree downvote.

I think people thought it was bad faith or deliberately provocative or something. Or people aren’t used to separating between “disagreement” and “I want to discourage this behaviour”. Or maybe they downvoted it because I stated something potentially harmfwl without justifying it, and they were worried that people would defer to me. I think I shouldn’t have posted the comment without more explanation, because it predictably would be misunderstood, wouldn’t help push communication norms further towards what I want, and made the forum feel less nice for people.

No I mean the one I replied to, your sub-comment

Why would your comment have made the forum feel less nice for people? Sincerely curious.

Something like, they misinterpret my comment as if written from a culture full of narcissistic/misanthropic/bitter people, and it makes them feel marginally more like the forum is partially a home for those kinds of people. I did use very strong/rude language, which I now regret. Mental health professionals are good folk, and I should’ve been kinder in my critique.