Is Democracy a Fad?

This cross-post from my personal blog explains why I think democracy will probably recede within the next several centuries, supposing people are still around.

The key points are that: (1) Up until the past couple centuries, nearly all states have been dictatorships. (2) There are many examples of system-wide social trends, including the rise of democracy in Ancient Greece, that have lasted for a couple centuries and then been reversed. (3) If certain popular theories about democratization are right, then widespread automation would negate recent economic changes that have allowed democracy to flourish.

This prediction might have some implications for what people who are trying to improve the future should do today (although I’m not sure what these implications are). It might also have some implications for how we should imagine the future more broadly. For example, it might give us stronger reasons to doubt that future generations will take inclusive approaches to any consequential decisions they face.[1]

Introduction

There’s a strange new trend that’s been sweeping the world. In recent centuries, you may have noticed, it has become more and more common for people to choose their own leaders. Five thousand years after states first emerged, democracy has been taking off in a big way.

The average state’s level of democracy over the past two hundred years. States with sub-zero scores are more autocratic than democratic.[2]

If you follow politics, then you’ve probably already heard a lot about democracy. Still, though, a quick definition might be useful. In a proper democracy, the state’s most important figures are at least indirectly chosen through elections. A large portion of the people ruled by the state are allowed to vote, these votes are counted more-or-less accurately and more-or-less equally, and there’s no truly serious funny business.[3]

Proper democracies are something new. For most of the past five thousand years, dictatorship has been the standard model for states. We don’t know much about the first state, Uruk, but the most common theory is that it was a theocracy ruled by a small priestly class. Monarchy emerged a bit later, spread across the broader Near East, and then stuck around in one form or another for thousands of years.

Many archeologists suspect these little bowls were used to ration out grain to people doing forced labor. They are also by far the most common artifact found around Uruk, which is often taken as an ominous sign.

In other parts of the world, small states with noteworthy democratic elements have emerged from time to time. Certain small states in Greece, as the most famous example, were borderline-proper democracies for a couple hundred years. However, if there was any trend at all, then the trend was toward more consistent and complete dictatorship. States with noteworthy democratic elements tended to lose these elements over time, as they either expanded or fell under the influence of larger states.[4] No sensible person living one thousand years ago would have predicted the recent democratic surge.

It’s natural to wonder: Will this rise in democracy last? Or will democracy turn out to be only a passing fad—something like the Ice Bucket Challenge of regime types?[5]

Let’s suppose, to be more specific, that one thousand years from now people and states still at least kind of exist. How surprised should we be if democracy is no more common then than it was in the year 1000AD?

An Outside View

One way to approach this question is to think hard about history, political science, economics, the future of technology, and all that. Another way to approach the question is just to look at the long-run trend.

The trend, again, is roughly this: Democracy was very rare for about five thousand years, then became common over the course of about two hundred years. There was also a period of major backsliding in the middle of its recent rise.

At first glance, this pattern is not very reassuring. Two hundred years of history normally says very little. There are plenty of examples of social trends that reversed themselves after only a couple hundred years. The famous trend toward greater democracy in Ancient Greece, as an especially pointed example, pretty much burned out after a few centuries.

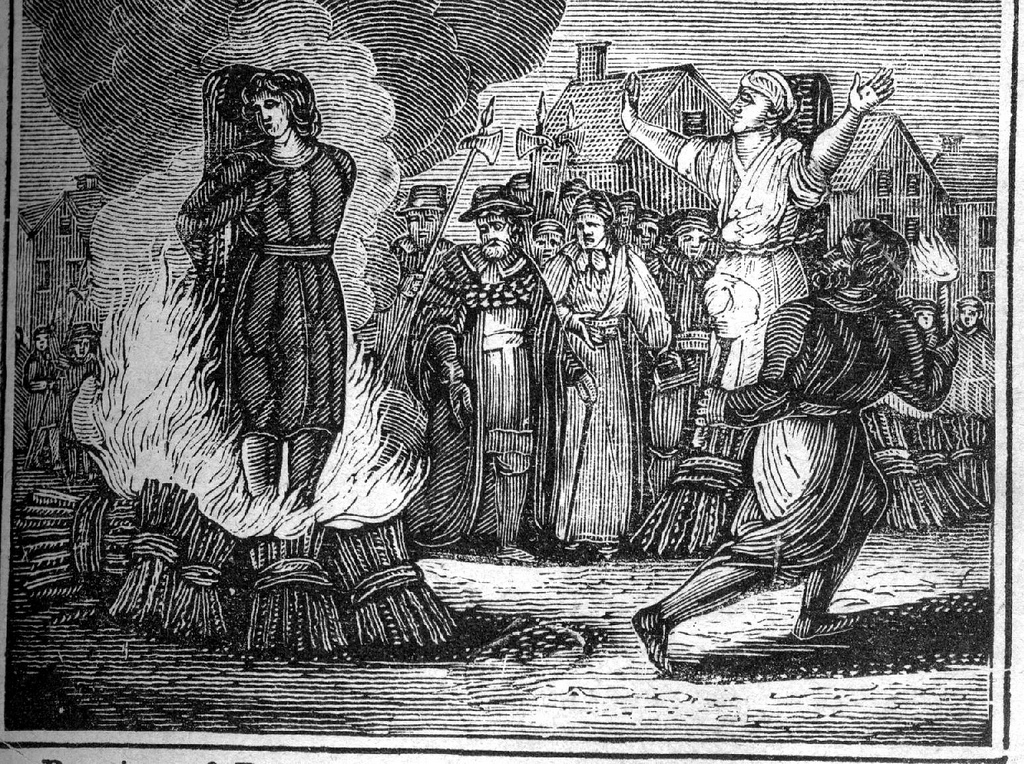

As a very different example, consider the rise of witch-hunting in early modern Europe. Toward the beginning of the sixteenth century, the practice took off very quickly. Tens or even hundreds of thousands of people were killed. By the early eighteenth century, though, the practice had essentially vanished again. Over a couple hundred years, the cultural wave rose and then broke.

Around 1500AD, Europeans started doing a lot of this. A couple centuries later, they thought better of it.

Some trends have survived for longer without reversals. For example, after nearly two thousand years, the spread of Islam and Christianity still have not been reversed. Some aspects of Ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern religion also seem to have survived for thousands of years. Certain very foundational trends, like the rise of states itself, also show no signs of reversing.

For about three thousand years, mummification was an important cultural practice in Egypt. Then nearly everyone became Christian.

Ultimately, if all we knew about the spread of democracy is that there has been a two-century trend, then I think that any strongly optimistic take would be a mistake. Democracy could keep spreading and then stick around. We know, though, that centuries-long social trends often reverse themselves.[6] We also know that dictatorship has been the standard mode of government for nearly all of recorded history.

Why So Much Democracy, All of a Sudden?

Of course, there are theories about why democracy has taken off. We probably shouldn’t trust any of them too much, since they are very hard to confirm. Still, so long as we keep their limits in mind, they can help us make slightly less blind predictions about the future of democracy.

One popular group of theories points the finger at industrialization. The Industrial Revolution began at roughly the same time as the rise of democracy. Looking across different countries, there is also a clear statistical link between industrialization and democratization. It is natural to wonder whether modern economic conditions are somehow more conducive to democracy than pre-modern conditions were.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (A&R) have developed one influential economic framework for thinking about democratization. They argue that elites have a natural resistance to democracy, because democratization involves giving up power and subjecting themselves to policies favored by commoners. This resistance can decline if elites become less afraid of the policies that commoners support. It can also decline if elites become more afraid of revolts by disaffected commoners.[7][8]

A&R suggest that industrialization helps to harmonize the policy preferences of common people and elites. In pre-industrial economies, the wealth of elites tends to be tied up in huge tracts of land. They allow or force farmers to work the land, while taking a large portion of what these farmers produce. Elites essentially do not work, beyond their military service, or contribute much to economic growth. Income polarization is unsurprisingly extreme. In this economic context, it is natural for ordinary people to take an interest in radical land redistribution. Demands for land reform have been a cornerstone of populist movements in agrarian societies.

The Roman tribune Gaius Gracchus advocated for land reform and the expansion of voting rights. The etching of him running for his life, a bit later on, was only available in a small image size.

In an industrial society, by contrast, it is more difficult and disruptive to confiscate the sources of elite wealth. Capital is both less divisible and more mobile than land. For example, forcibly dividing ownership of a large car factory is messier and more likely to reduce its output than forcibly dividing up a tract of land. If radical distribution is on the table, then car manufacturers can also threaten to build their factories elsewhere or to simply not build them at all. Landowners cannot really make an equivalent threat. In addition, in an industrialized society, levels of income polarization tend to be lower. These factors may make ordinary people less likely to demand extreme levels of redistribution.

Furthermore, elites in industrialized societies should be less bothered by moderate redistribution. Economic development tends to increase the value of having an educated and entrepreneurial workforce. Popular redistributive programs such as tax-funded primary schools therefore begin to benefit elites too. Industrial elites ultimately have less reason to worry about the policies that voters will demand.

At the same, these elites have more reason to worry about what will happen if they refuse democratic reforms. For one thing, industrialization tends to be associated with urbanization. Urban populations likely find it easier to coordinate and form up into crowds that can credibly threaten centers of power. For another thing, the early stages of industrialization seem to be associated with a greater reliance on mass armies. Armed and mobilized commoners are in a better position to threaten elites. They can also exert pressure simply by resisting conscription unless they receive political concessions. Finally, political turmoil of any kind may cause more economic damage in industrialized societies than in agricultural societies. Lengthy and complex industrial supply chains allow the damage to compound.

In summary, compared to landed aristocrats, industrial elites have less to fear from democracy and more to fear from standing in its way. The Industrial Revolution has helped democracy to spread by softening elite resistance.[9]

There are a lot of historical cases that this story can’t explain on its own.[10] There are also some obviously important factors, especially cultural factors, that the general A&R framework ignores. I do suspect, though, that the story captures some respectable portion of the truth.[11]

Automation and Democracy

At first glance, some aspects of the above story are reassuring. Unless something goes horribly wrong, like full-on nuclear war or worse-than-anyone-thought climate change, most developed states are very unlikely to deindustrialize in the coming centuries. We should expect a lot of the recent economic changes that have supported democracy to stick.

On the other hand, we should not imagine that the economies of developed states will stay frozen in amber. Changes will keep coming — and some of these changes might push states back toward dictatorship. I feel especially nervous about the long-run impact of automation.

Most AI researchers believe that automated systems will eventually be able to perform all of the same tasks that people can. According to one survey, the average researcher even believes that this milestone will probably be reached within the next century-and-a-half. I’m unsure whether this particular estimate is reasonable. I do agree, though, that something like complete automation will probably become possible eventually.[12] I expect human labor to lose nearly all of its value once it becomes cheaper and more effective to simply use machines to get things done.[13]

If human labor loses its value, then this strikes me as bad news for democracy. It would seem to eliminate most of the incentive for elites to accept democratization. If the suppression of protests can be automated, using systems that are more effective than humans, then public revolt would become much less threatening. Striking and resisting conscription would also, obviously, become totally obsolete as a method of applying public pressure. Elites would have weaker incentives to make any concessions at all.

Furthermore, it seems to me, elites would have more to lose from democracy. In a world without work, the two central forms of income would be welfare payments and passive income from investments. We should not be surprised if there is a huge lower class that depends on welfare payments to survive. Demands for radical redistribution might then become more common, for a few reasons: income polarization would be higher, redistribution would be simpler and less disruptive, and wealth levels would become extremely transparently divorced from merit. More moderate forms of redistribution would also stop benefitting elites at all. The resources and freedoms of common people would simply have no connection to economic growth.[14][15]

The Valley of Democracy

One perspective on our place in history is that we are living in the little valley between industrialization and widespread automation. This valley has just the right conditions for democracy to flourish. When we leave the valley, though, we will once again be entering territory where democracy can hardly grow at all.

Of course, maybe whatever economic changes are coming will be fine for democracy. No one can make confident predictions here. Still, if I had to bet, I would bet against democracy. If we put aside economic theories and simply note the extreme rareness of democracy, throughout nearly the entire history of states, then a major decline in democracy seems more likely than not. If we take economic theories into account, then the analysis becomes much murkier. To my mind, though, this analysis is not reassuring. We should mourn democracy if it dies, but we shouldn’t be surprised.[16]

Thank you, especially, to Allan Dafoe for conversations on the political impact of AI.

- ↩︎

Disclaimer: I haven’t actually read all that much about democracy. I would not be stunned if parts of this post are silly or misleading in ways that experts could easily identify.

- ↩︎

The democracy ratings used to produce this graph are taken from the PolityV dataset. Although the dataset is widely used by political scientists, and the broad historical picture it paints is probably roughly right, some its individual ratings are admittedly bizarre. For example, according to the Polity team, the United States is currently less democratic than it was in 1845.

- ↩︎

“Proper democracy” isn’t a standard term. It is loosely equivalent, though, to what David Stasavage calls “modern democracy.” In his book The Decline and Rise of Democracy, Stavage mainly uses the concept of “modern democracy” to draw a contrast with “early democracy.” An early democracy is a complex society that does not qualify as a modern democracy, but that still places some significant constraints on leaders and still allows for some significant public participation. Participation can take a number of forms and may emphasize discussion more than it emphasizes elections. Opportunities to participate are also usually much more limited for common people than for elites.

The Roman Republic is one famous state that qualifies as an “early democracy.” In general, in the premodern world, early democracies were not extremely rare, although they were most likely to arise in places where states were small and weak.

- ↩︎

From The Decline and Rise of Democracy:

Over time, early democracy persisted in some societies, but it died out in many others. It did so as societies grew in scale; it also did so as rulers acquired new ways of monitoring production; it did so finally when people found it hard to exit to new areas. It is for all these reasons that the title of this book refers first to a decline in early democracy and then to the rise of modern democracy.

- ↩︎

People have been debating the robustness of the rise of democracy for a long time. My impression is that, among proponents of democracy, the dominant intellectual mood has ranged from quasi-religious faith in the trend (in response to early progress and Enlightenment-era interpretations of history) to grave doubt (in response to the rise of fascism and communism) to incautious optimism (in response to the end of the Cold War) to gnawing worry (in response to the past twenty years).

Here are some long quotes that give a taste of intellectual thought in each era.

From Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1831):

Whithersoever we turn our eyes we shall witness the same continual revolution throughout the whole of Christendom. The various occurrences of national existence have everywhere turned to the advantage of democracy; all men have aided it by their exertions: those who have intentionally labored in its cause, and those who have served it unwittingly; those who have fought for it and those who have declared themselves its opponents, have all been driven along in the same track, have all labored to one end, some ignorantly and some unwillingly; all have been blind instruments in the hands of God.…

The whole book which is here offered to the public has been written under the impression of a kind of religious dread produced in the author’s mind by the contemplation of so irresistible a revolution, which has advanced for centuries in spite of such amazing obstacles, and which is still proceeding in the midst of the ruins it has made. It is not necessary that God himself should speak in order to disclose to us the unquestionable signs of His will; we can discern them in the habitual course of nature, and in the invariable tendency of events: I know, without a special revelation, that the planets move in the orbits traced by the Creator’s finger. If the men of our time were led by attentive observation and by sincere reflection to acknowledge that the gradual and progressive development of social equality is at once the past and future of their history, this solitary truth would confer the sacred character of a Divine decree upon the change. To attempt to check democracy would be in that case to resist the will of God; and the nations would then be constrained to make the best of the social lot awarded to them by Providence.

From Jean-Francois Revel’s in “Can the Democracies Survive?” (1984):

Democracy may, after all, turn out to have been a historical accident, a brief parenthesis that is closing before our eyes.

If so, in its modern sense of a form of society reconciling governmental efficiency with legitimacy, authority with individual freedoms, democracy will have lasted a little over two centuries, to judge by the speed at which the forces bent on its destruction are growing. And, really, only a tiny minority of the human race will have experienced it. In both time and space, democracy fills a very small corner. The span of roughly two-hundred years applies only to the few countries where it first appeared, still very incomplete, at the end of the 18th century. Most of the other countries in which democracy exists adopted it under a century ago, under half a century ago, in some cases less than a decade ago.

Democracy probably could endure if it were the only type of political organization in the world. But it is not basically structured to defend itself against outside enemies seeking its annihiliation, especially since the latest and the most dangerous of these external enemies–Communism–parades as democracy perfected when it is in fact the absolute negation of democracy, the current and complete model of totalitarianism.

From Philip Slater and Warren Bennis’s “Democracy is Inevitable (1990):

[B]arring some sudden decline in the rate of technological change, and on the (outrageous) assumption that war will somehow be eliminated during the next half-century, it is possible to predict that…democracy will be universal. Each revolutionary autocracy, as it reshuffles the family structure and pushes toward industrialization, will sow the seeds of its own destruction, and democratization will gradually engulf it.

We might, of course, rue the day. A world of mass democracies may well prove homogenized and ugly. It is perhaps beyond human social capacity to maximize both equality and understanding on the one hand, diversity on the other. Faced with this dilemma, however, many people are willing to sacrifice quaintness to social justice, and we might conclude by remarking that just as Marx, in proclaiming the inevitability of communism, did not hesitate to give some assistance to the wheels of fate, so our thesis that democracy represents the social system of the electronic era should not bar these persons from giving a little push here and there to the inevitable.

From Anne Applebaum’s Twilight of Democracy (2020):

It is possible that we are already living through the twilight of democracy; that our civilization may already be heading for anarchy or tyranny, as the ancient philosophers and America’s founders once feared; that a new generation of clercs, the advocates of illiberal or authoritarian ideas, will come to power in the twenty-first century, just as they did in the twentieth; that their visions of the world, born of resentment, anger, or deep, messianic dreams, could triumph. Maybe new information technology will continue to undermine consensus, divide people further, and increase polarization until only violence can determine who rules. Maybe fear of disease will create fear of freedom.

Or maybe the coronavirus will inspire a new sense of global solidarity. Maybe we will renew and modernize our institutions. Maybe international cooperation will expand after the entire world has had the same set of experiences at the same time: lockdown, quarantine, fear of infection, fear of death. Maybe scientists around the world will find new ways to collaborate, above and beyond politics. Maybe the reality of illness and death will teach people to be suspicious of hucksters, liars, and purveyors of disinformation.

Maddeningly, we have to accept that both futures are possible. No political victory is ever permanent, no definition of “the nation” is guaranteed to last, and no elite of any kind, whether so-called “populist” or so-called “liberal” or so-called “aristocratic,” rules forever. The history of ancient Egypt looks, from a great distance in time, like a monotonous story of interchangeable pharaohs. But on closer examination, it includes periods of cultural lightness and eras of despotic gloom. Our history will someday look that way too.

I think this whipsaw pattern suggests that people sometimes give too much weight to recent events and sub-trends when thinking about the future of democracy. For example, this past year, public intellectuals who have written about the future of democracy have tended to dwell a lot on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic. If someone writes a new history of democracy in 2100, though, I’m skeptical that the pandemic will actually show up in a major way. Similarly, I think we probably shouldn’t read too much into reports that democracy has recently been experiencing a global recession. Although the past decade should make us feel somewhat more worried, our overall predictions for the world shouldn’t change very much.

- ↩︎

You could argue, on the other hand, that it’s unfair to draw an analogy between the modern rise of democracy and premodern trends that burned out after a few centuries. The pace of economic and technological change is much faster in modern times than it was before the Industrial Revolution. If a political trend can survive for two centuries in the modern world, then this may be more impressive than surviving for a couple centuries when the background pace of change is low.

On the other other hand, if change will be just as fast (or even faster) in the coming centuries, then maybe this gives us an opposing reason to expect existing trends to burn out quickly. I think these two considerations might balance each other out.

- ↩︎

An important nuance to A&R’s theoretical framework, which I’ve glossed over, is the idea that democractization is also a solution to a commitment problem faced by elites. You might think elites could placate commoners simply by making policy concessions, while still retaining their dictatorial powers. However, A&J point out that promises of future concessions can be difficult to trust. Simply stepping out onto your balcony and anncouning “I’ll never screw you people over again” probably won’t do much much to resolve a crisis. Actively reducing your ability to screw common people over in the future, by moving from dictatorship to democracy, might produce better results.

- ↩︎

One alternative framework for explaining democratization is the elite competition framework. This framework emphasizes conflict between political elites and economic elites with limited political power. Ben Ansell and David Samuels argue that economic elites have an interest in supporting democratization as a way of protecting their wealth from political elites. They correctly believe that they have less to fear from pro-redistribution voters than they have to fear from political elites with extractive tendencies. Industrialization tends to support democratization, according to this theory, because it creates a large new class of wealthy people with limited political authority.

- ↩︎

We can break down the A&R story down into three high-level pieces, which each seem pretty plausible to me:

First: The prevalence of democracy depends (in part) on how strenuously elites oppose it.

Second: The level of elite resistance depends (in part) on the costs and benefits that democratization poses for them.

Third: Industrialization has tended to raise these benefits and lower these costs.

- ↩︎

If we want to explain why India is a long-standing democracy and China is still a dictatorship, for example, then talking about industrialization is not going to do us much good. Clearly many other factors matter too.

- ↩︎

The general idea that economic change can be a major driver of political change is also supported by the Neolithic Revolution. The low population densities of hunter-gatherers, along with their inability to store large food surpluses, made it nearly impossible for states to emerge for most of human history. When people transitioned to sendentary agricultural production, in several different parts of the world, this transition tended to be followed by the emergence of states. The causal link in this case is very clear.

The Neolithic Revolution is also an interesting case to consider, because it shows us that economic change does not always push in the direction of greater liberty. Hunter-gatherer groups tend to be quite egalitarian, often take consensus-oriented approaches to major decisions, and rarely hold slaves. The rise of states therefore meant the rise of inequality, social hierarchy, and slavery.

- ↩︎

When thinking about the future of automation, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the human brain is just a physical object. It was produced through a physical process, without even a blueprint or guiding plan. At first glance, then, there is no obvious reason to think that engineered objects will never be able to match its functionality. We also should keep in mind that the entire field of computer science is less than a century old. Furthermore, for most of this time, computer scientists lacked access to anything close to the amount of computing power used by human brains. The fact that we have not yet achieved anything close to full automation is not very telling.

- ↩︎

Complete automation is importantly different than partial automation. When only some jobs are automated away, there will often an increase in demand for workers to perform jobs that haven’t yet been automated. This dynamic has allowed average wages to rise despite the tremendous amount of automation that has followed the Industrial Revolution. The dynamic should break down, though, if we eventually approach full automation. See this paper and this paper for discussions that touch on this point.

- ↩︎

All of my analysis of the impact of complete automation assumes that people still at least kind of exist and call the shots politically. If AI systems call the shots by this point in history, on the other hand, then the appropriate analysis becomes very different.

More abstractly, I suppose, the one really necessary assumption behind my analysis is that there is some kind of thing that has political power but no longer has a major role to play in production. These things could in principle be normal humans, really heavily biologically modified humans, brain emulations, or any other sci-fi staple. The less human the future is, though, the less I trust my analysis or even the general concept of democracy to be applicable. It’s also conceivable that there will be only be a short window of time between complete automation and the world becoming a pretty much unrecognizably post-human fever dream. In that case, my analysis of the impact of complete automation might only apply to a brief (but still potentially consequential) moment in history.

- ↩︎

I can also see at least a couple ways that complete automation could bolster democracy. First, by dramatically increasing economic output, complete automation could reduce elite fears about redistribution. If there are strongly diminishing returns on pie, then, when the size of a pie grows, the difference between the value of eating the whole pie and the value of eating half-the-pie shrinks. In a subjective sense, then, elites in a wealthy world may have less to lose from wealth redistribution.

Second, automation might make it easier to “lock in” democratic insitutions. If you can automate much of the work involved in enforcing the law, counting votes correctly, and so on, then it may become much easier to safeguard these institutions against future meddling. On the other hand, by the same logic, automation might also make it easier to “lock in” dictatorial institutions.

- ↩︎

I feel conflicted about exactly how likely the survival of democracy is. Still, I think it’s a good habit to attach numbers to your predictions, so I’ll try to say something more precise.

Let’s suppose that one thousand years from now individual people still at least sort of exist, with a population of at least one million, and still largely govern themselves. I think, then, that there is something like a 4-in-5 chance that the portion of people living under a proper democracy will be substantially lower than it is today. For reference, depending on how you draw the line, between ten and fifty percent of people currently live under a proper democracy.

The main thing driving my prediction is the observation that democracy is very rare historically. If the recent wave of democratization is mostly a cultural phenomenon, which doesn’t reflect some deeper form of economic determinism, then historical analogies suggest that we should expect the wave to crest eventually. We’ll probably regress back toward the cultural baseline sometime in the next thousand years. If the wave does reflect a kind of economic determinism, on the other hand, then it’s not clear what we should predict. There are some at least vaguely plausible stories we can tell in which automation seriously harms democracy. These particular stories might turn out to be speculative nonsense, of course, but even if we dismiss them as such, I don’t think we can trust future economic changes to support democracy. At best, I think, we could suppose that the odds of a net positive impact and the odds of a net negative impact are roughly even.

[[EDIT: After some reflection, 4-in-5 feels too high to me. For a mix of reasons, some raised in the comment section, I’ll now give 65% as my mostly made-up credence.]]

- Long-term risks from ideological fanaticism by (12 Feb 2026 23:25 UTC; 194 points)

- What Helped the Voiceless? Historical Case Studies by (11 Oct 2020 3:38 UTC; 132 points)

- Long-term risks from ideological fanaticism by (LessWrong; 12 Feb 2026 23:26 UTC; 98 points)

- GovAI Annual Report 2021 by (5 Jan 2022 16:57 UTC; 52 points)

- EA Updates for April 2021 by (26 Mar 2021 14:26 UTC; 39 points)

- EA Forum Prize: Winners for March 2021 by (22 May 2021 4:34 UTC; 26 points)

- [Cause Exploration Prizes] Dynamic democracy to guard against authoritarian lock-in by (24 Aug 2022 10:53 UTC; 12 points)

- 's comment on The Dictatorship Problem by (LessWrong; 11 Jun 2023 20:08 UTC; 11 points)

- GWWC April 2021 Newsletter by (22 Apr 2021 7:09 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on Propose and vote on potential EA Wiki entries by (16 Mar 2021 2:11 UTC; 4 points)

- 's comment on Propose and vote on potential EA Wiki entries by (25 Mar 2021 5:16 UTC; 4 points)

- [cross-post with EA Forum] The EA Forum Podcast is up and running by (LessWrong; 5 Jul 2021 21:52 UTC; 3 points)

Thanks for this post! I was impressed by how you managed to make it substantive, nuanced, concise, and funny all at once.

There seem to be at least two major types of outside views / reference classes that one could bring to bear on this question:

Historically, what proportion of societies have been proper democracies?

Or related things like “At what proportion of years since civilization emerged has proper democracy been as common as it is today”, or “What has been the average proportion of people living in proper democracy since civilizatin emerged?”

Historically, how many trends that lasted a couple centuries stuck around?

Or related things like “Historically, what is the average length of time for which a trend lasts, given that it’s already lasted a couple centuries?”

You argue convincingly that the first type of reference class bodes poorly for democracy. But regarding the second type of reference class, you seem to only say:

But you don’t give examples or statistics, and “often” is consistent with (for example) “5% of a very large set, thus totally tens of instances”. And I know of at least some other social trends that lasted a couple centuries and then much longer, including lasting to the present day (I mainly have in mind things discussed in Henrich’s WEIRDest People in the World).

So I feel like it’d make sense to look closer at that second type of reference class. I also feel like, until we do so, it might be premature to predict that “[one thousand years from now, given certain specified conditions] there is something like a 4-in-5 chance that the portion of people living under a proper democracy [would] be substantially lower than it is today”. (To be clear, I mean that it might make sense to stick a bit closer to 50⁄50 until we look closer at the second type of reference class; I’m not saying it was premature of you to make any quantitative prediction, and I appreciate you doing so.)

This also makes me think that it might be very useful for someone to:

Compile a dataset of “civilization-related trends” (could be social, moral, economic, political, etc., just not things like biological or physical trends)

Classify them in ways that helps us get a sense of how relevant one trend is to another

Thereby come up with base rates for the persistence of certain types of trends

At first glance, I’d guess that:

Any random EA should be able to do a better-than-nothing first pass at this in just a week or so

That first pass might already be quite useful

It could then be refined and expanded over time

Does anyone know if something like this has been tried? Would it be tractable and useful? I guess maybe there’s some relevant work in the literature on cultural persistence / persistence studies (I haven’t looked into that myself)?

Hi Michael, I think this is a great comment! I would be really interested in a rough ‘civilizational trends database’ or anything that could help clarify what a sensible prior for social trend persistence would be.

I’m not exactly sure how this would work, but one trick might be to pick a few well-document times/regions in world history and try to log trends that historians think are worth remarking on. For example, for the late Roman Empire, the ‘religious trends’ subset of the database would include both the rise of Christianity (ultra-robust) and the rise of Sol Invictus worship (not nearly as robust). Although, especially for older periods, shorter-lived trends might be systematically under-discussed/under-recorded.

I think the closest things we’ve got that’s similar to this are:

Luke Muehlhauser’s work on ‘amateur macrohistory’ https://lukemuehlhauser.com/industrial-revolution/

The (more academic) Peter Turchin’s Seshat database: http://seshatdatabank.info/

Great post! Like MichaelA, I’d be really interested in something systematic on the reversal of century-long trends in history.

With respect to the ‘outside view’ approach, I wondered what you would make of the rejoinder that actually over the very long autocracy is the outlier—provided that we include hunter-gatherers?

On the view I take to be associated with Christopher Boehm’s work, ancestral foragers are believed to have exhibited the fierce resistane to political hierarchy characteristic of mobile foragers in the ethnographic record, relying on consensus-seeking as a means of collective decision-making. In some sense, this could be taken to indicate that human beings have lived without autocracy and with something that could be described as vaguely democratic throughout virtually all of its history. Boehm writes: “before twelve thousand years ago, humans basically were egalitarian. They lived in what might be called societies of equals, with minimal political centralization and no social classes. Everyone participated in group decisions, and outside the family there were no dominators” (Hierarchy in the Forest pp. 3-4)

Obviously, you can make the rejoinder that the relevant reference class should be ‘states’ and so shouldn’t include acephalous hunter-gatherer bands, but by the same logic I take it someone could claim that the reference class should be narrowed further to ‘industrialised states’ when we make our outside view forecast about how long democracy will be popular. The difficulty of fixing the appropriate reference class here seems to me to raise doubts about how much epistemic value can be derived from base rates and seems to require predictions to be based more firmly in the sorts of causal questions that are focal later in your post: understanding why hunter-gatherer bands are egalitarian, agrarian states aren’t, and industrialized economies have tended to be.

That’s an interesting consideration.

I just came across a paper that argued that pre-historic hunter-gatherers likely on average lived in less egalitarian societies than previously thought (though there was substantial variation).

See also this Twitter thread and this Aeon article. I don’t know what the consensus of the field is, however.

Conversely, there’s a hypothesis that the Indus Valley Civilization was more egalitarian, unlike other Bronze Age civilizations in the Near East and China that were hierarchical. See: this Twitter thread (also by Manvir Singh) and this article (by Patrick Wyman).

Interesting comment.

I think there are (almost?) always multiple reference classes, outside views, or base rates one could use, and that one (almost?) always has to get at least a bit inside-view-y when deciding how much weight to give each (or just which to include vs exclude). This also leads me to strongly prefer the term “an outside view”; I think “the outside view” implies we’re facing a simpler situation than we’re ever actually facing.

(I definitely do think considering outside views is very useful, though!)

Some relevant posts on this issue, in descending order of relevance:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/SxpNpaiTnZcyZwBGL/multitudinous-outside-views

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/iyRpsScBa6y4rduEt/model-combination-and-adjustment

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/SBbwzovWbghLJixPn/what-are-some-low-information-priors-that-you-find

Interesting post! If you wanted to read into the comparative political science literature a little more, you might be interested in diving into the subfield of democratic backsliding (as opposed to emergence):

A third wave of autocratization is here: what is new about it? Lührmann & Lindberg 2019

How Democracies Die. Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt 2018

On Democratic Backsliding Bermeo, Nancy 2016

Two Modes of Democratic Breakdown: A Competing Risks Analysis of Democratic Durability; Maeda, K. 201

Authoritarian Reversals and Democratic Consolidation in American Political Science Review; Milan Svolik; 2008

Institutional Design and Democratic Consolidation in the Third World Timothy J. Power; Mark J. Gasiorowski; 04/1997

What Makes Democracies Endure? Jose Antonio Cheibub; Adam Przeworski; Fernando Papaterra Limongi Neto; Michael M. Alvarez 1996

The breakdown of democratic regimes: crisis, breakdown, and reequilibration Book by Juan J. Linz 1978

One of the common threads in this subfield is that once a democracy has ‘consolidated’, it seems to be fairly resilient to coups and perhaps incumbent takeover.

I certainly agree that how this interacts with new AI systems: automation, surveillance and targeting/profiling, and autonomous weapons systems is absolutely fascinating. For one early stab, you might be interested in my colleagues’:

Tackling threats to informed decision-making in democratic societies: Promoting epistemic security in a technologically-advanced world (see here for a news article).

Thanks for the reading list!

I looked into the backsliding literature just a bit and had the initial impression it wasn’t as relevant for long-run and system-wide forecasting. A lot of the work seemed useful for forecasting whether a particular country might backslide (e.g. how large a risk-factor is Trump in the US or Modi in India?), or for making medium-term extrapolations (e.g. has backsliding become more common over the past decade?). But I didn’t see as clear of a way to use it to make long-run system-level predictions.

The point that democratic institutions tend to be naturally sticky does seem potentially important. I’m initially skeptical, though, that any inherent stickiness would be strong enough to keep democracy going for centuries if the conditions that allowed it to emerge disappear. It also seems like there should be heavy (although imperfect) overlap between factors that support the emergence of democracy and factors that support the persistence of democracy.

Out of curiosity, if you have a view, do you have the sense that the backsliding literature should make people substantially more or less optimistic about the future of democracy (relative to the views in this post)?

I would say more optimistic. I think there’s a pretty big difference between emergence (a shift from authoritarianism to democracy) - and democratic backsliding, that is autocratisation (a shift from democracy to authoritarianism). Once that shift has consolidated, there’s lots of changes that makes it self-reinforcing/path-dependent: norms and identities shift, economic and political power shifts, political institutions shift, the role of the military shifts. Some factors are the same for emergence and persistence, like wealth/growth, but some aren’t (which I would say are pretty key) like getting authoritarian elites to accept democratisation.

Two books on emergence that I’ve found particularly interesting are

The international dimensions of democratization: Europe and the Americas; edited by Laurence Whitehead 2001 (on underplayed international factors)

Conservative parties and the birth of democracy; Daniel Ziblatt 2017 (on buying off elites to accept this permanent change)

However as I said, the impact of AI systems does raise uncertainty, and is super fascinating.

Something I’m very concerned about, which I don’t believe you touched, is the fate of democracies after a civilizational collapse. I’ve got a book chapter coming out on this later this year, that I hope I may be able to share a preprint of.

Democracies did not exist in the premodern world for one main reason; they were bad at war. Revolutions and republics did form in the Medieval period, particularly in capital-intensive trade hubs like Northern Italy and Northern Germany. However, most were quickly crushed under a wave of poorly armed peasant-soldiers from the coercive states next door.

A major reason for democracies rise in the 17th-21st centuries because democracies suddenly became much better at warfare than all other systems, and have maintained this advantage ever since. The first state to create a democratic nation-state and harness it to war was the Dutch in the Dutch revolt, who shocked Europe by defeating the Habsburg Empire. Shortly afterward Britain formed a democracy-nation hybrid who set the standard for military power. All major world wars since have been resounding Democratic victories., from the War of Jenkin’s Ear to the Cold War. The main advantages of the democratic system are

Modern democracies had both large populations and property rights for capital, combining the two great advantages of previous state forms. Some autocracies have greatly improved their ability to accumulate capital to close this gap (Fascist Italy, China, Soviet Union).

Leaders pay a higher cost for defeat

Democracies can more credibly issue bonds (democratic advantage has faded over time)

Democracies rarely have to coup proof (divide and purge the military to prevent coups)

This advantage should be completely irrelevant going forward. China and Russia may democratize, giving the democracies a clean sweep of the security council powers. But the democracies are already at maximum influence in many stable anocracies like Morocco and Jordan.

Interesting comment!

I’m not sure I understand what you mean.

Are you saying that basically all countries that democracies might have strategic conflicts with will also become democracies, such that the warfighting advantage democracies have will become irrelevant (since there’ll be a level playing field)? But if that’s what you’re saying, then it seems to me that the advantage would still be relevant in the important sense that any country which “backslid” from being a democracy would suddenly have a disadvantage in war?

It seems like it would be useful to look more closely at why democracies have fallen, too. The causes of the fall of democracy might be not be the “opposites” or absence of the causes of its rise. Sometimes citizens willingly vote for the concentration of power and movements away from democracy! Sometimes it’s an unwanted takeover.

Hey Ben,

Thanks for putting this together—I always find your writing to be simultaneously very readable and also dense with novel ideas, which is rare to see.

As part of a contracting position with the Open Philanthropy Project, I have been looking into different metrics on the prevalence and success of democratic forms of governance over time. One piece of data that we were interested in but couldn’t find in the existing literature was the percent of GDP in democracies vs non-democracies over time. To answer this question, I combined data from Polity on categorizing regime type over time with the IMF’s data on nominal GDP. I ended up only going back to 1980, because before then I started to lose a lot of reliable GDP data for smaller countries. You can find my analysis here—in particular I recommend looking at the first two sheets that graph percent of GDP by regime type. I used Polity’s classifications for determining which countries counted as democracies, autocracies, and in between “anocracies.” (Disclaimer that I did this independently, may have messed something up, and it did not undergo the sort of review that would be associated with anything formally released by Open Phil. )

Overall, the main takeaway was that, at least from 1980 to today, democracies hold a disproportionate percentage of income in comparison to their population. (Compare with Our World in Data’s graph on percent of world citizens living in a democracy over time here.) However, while the percent of nominal income in democracies was increasing from 1980 to ~2000, after that it has started to reverse, largely because of increased GDP in authoritarian China. If one looks only at “western democracies” as the authors do here, the trend for relative financial power of non-democratic governments becomes more pronounced. I don’t think these analysis rebut any of your core points—the fact that this graph only covers 38 years underscores that these trends could easily be historical anomalies that disappear in the long run—but hopefully it adds an additional metric to use in thinking about the future prospects of democratic government.

Thanks for sharing this, Nathan! Very interesting graph (and a metric I haven’t ever thought to consider.)

I’m curious if you have any views on what we should take away from trends in “the portion of output produced by democracies” vs. “the portion of people living under democracy” vs. “the portion of states that are democratic.”

Am I right to think that “portion of output produced by democracies” is most useful as a measure of the global power/influence of democracies? If so, that does seem like an interesting trend to track. I could also imagine it being interesting to look at secondary metrics of national power, if you haven’t already. For example, I think some IR scholars argue for the use of GDP multiplied by GDP-per-capita, based on the intuition that poor-but-highly-populated countries (e.g. Indonesia) seem to have less global power than their GDPs would suggest. You’re also probably already familiar with this sort of unprincipled metric of “national material capabilities” that international relations people sometimes use. Although my guess is that the trends would probably look pretty similar.

It seems like “portion of output produced by democracies” also functions as a combined metric of the prevalence of democracy, the strength of the development/democracy correlation, and the weakness of the (I think slightly negative?) population/democracy correlation. I suppose it’s a bad sign for democracy if any of these components decrease.

[[Edit: One more thought. If you haven’t already done this, it might also be interesting to look at trends in Polity-score-weighted GDP as a more continuous measure of the financial power of democracy. I think the trend would probably look about the same, since China’s polity score has been pretty stable over time, but there’s some chance it’d be interestingly different. I might also just do myself, out of curiosity.]]

Nice article!

I thought this sub-footnote deserved a bit more prominence:

When we think about what jobs are automatable, it seems that many relatively unintellectual jobs (plumber, nurse, carehome worker) are surprisingly hard to automate, especially those requiring a social component. In contrast, ‘AI developer’ seems potentially easier to do—we already have things like evolutionary algorithms and ML which are, in some sense, algorithms designing algorithms, and AI developers are often bizarrely interested in accelerating their own obsolescence. So it’s not obvious to me that there will be any positive length window of time between full automation and the end of human supremacy.

Even if there was a short positive window, it’s also possible that status quo bias might carry democracy over, as political convergence on locally optimal policy seems to be a slow process at best (e.g. the long coexistence of Parliamentary and Presidential systems, or of North and South Korea).

I agree with this—and agree I probably should have emphasized this caveat more!

The critical thing, in my mind, is whether humans (or something in that ballpark) are still largely governing themselves. This is consistent with broadly superhuman AI capabilities existing. For example, on a CAIS-like development trajectory, these superhuman AI capabilities might not even (for the most part) be embedded in very agential systems.

But if humans just totally lose control, or become just totally unrecognizable, then I think the analysis really breaks down. At a certain point, it’s hard even to understand what “democracy” would mean.

I think that’s a good point! The length of the window (and the gradualness of the transition to full automation) probably is very consequential.

I had a question that I think is semi-related to this thread, regarding your prediction:

Are you seeing this prediction as including scenarios in which TAI has been developed by then, but things are basically going well, at least one million beings roughly like humans still exist, and the TAI is either agential and well-aligned with humanity and deferring to our wishes[1] or CAIS-like / tool-like?

I think I’d see those scenarios as fitting your described conditions. And I think I’d also see them as among the most likely picture of a good, non-existentially-catastrophic future.[2] So I wonder whether (a) you don’t intend to be accounting for such scenarios, (b) you think they’re much less likely relative to other good futures than I do, or (c) you think good futures are much less likely relative to bad ones than I do?

A related uncertainty I have is what you mean by “individual people still at least sort of exist” in that quote. E.g., would you include whole brain emulations with a fairly similar mind design to current humans?

[1] This could maybe be like a more extreme version of how the US President is “agential” and makes many of the actual decisions, but US citizens still in a substantial sense “govern themselves” because the president is partly acting based on their preferences. (Though obviously that’s different in that there are checks and balances, elections, etc.)

[2] I think the main alternatives would be:

somehow TAI is never developed, yet we can still fulfil our potential

humans changing into or being replaced by something very different

TAI is aligned with our idealised preferences at one point, and then just rolls with that, doing good things but not in any meaningful sense still being actively “governed by human-like beings”

Caveat that I wrote this comment relatively quickly and think a lot of it is poorly operationalised and would benefit from better terminology.

Yep! I’m including these scenarios in the prediction.

I suppose I’m conditioning on either:

(a) AI has already been truly transformative, but people are still around and still meaningfully responsible for some important political decisions.*

(b) AI hasn’t yet been truly transformative , but people haven’t gone extinct

I actually haven’t thought enough about the relative probability of these two cases or my actual conditional probabilities for each of them. So my “4-in-5” prediction shouldn’t be taken as very rigorously thought through. I think the outside view is relevant to both cases, but the automation argument is only very relevant to the first case.

*I agree with your analogy here: People might be “meaningfully responsible” in the same way that US citizens are “meaningfully responsible” for US government actions, even though they only provide very occasional and simple inputs.

I’m a little torn here. I’ve gone back and forth on this point, but haven’t really settled on how much including emulations should or should not influence the prediction. (Another sign that my “4-in-5” shouldn’t be taken too seriously.)

If whole brains emulations have largely replaced regular biological people, and mostly aren’t doing work (because other AI systems can do better jobs for most relevant cognitive tasks), then the automation argument still applies. But we should also assume, if we’re talking about emulations, that there have been an incredible number of other changes, some of which might be much more relevant than the destruction of the value of labor. For example, surely the ability to make copies of an emulation has implications for the nature of voting.

So, although I still feel that automation pushes in the direction of dictatorship, in the emulation case, I do feel a bit silly making mechanistic or “inside view” arguments given how foreign this possible future is to us. I also think the outside view continues to be relevant. At the same time, though, there might be a somewhat stronger case for just throwing up our hands and beginning from a non-informative 50⁄50 prior instead of trying to think too hard about base rates.

Interesting, thanks.

So now I’m thinking that maybe your prediction, if accurate, is quite concerning. It sounds like you believe the future could take roughly the following forms:

There are no longer really people or they no longer really govern themselves. Subtypes:

Extinction

A post-human/transhuman scenario (could be good or bad)

There are still essentially people, but something else is very much in control (probably AI; could be either aligned or misaligned with what we do/should value)

There are still essentially people and they still govern themselves, and there’s “something like a 4-in-5 chance that the portion of people living under a proper democracy will be substantially lower than it is today”

That sounds to me like a 4-in-5 chance of something that might probably itself be an existential catastrophe (global authoritarianism that lasts indefinitely long), or might substantially increase the chances of some other existential catastrophe (e.g., because it’s harder to have a long reflection and so bad values get locked in)

So that makes it sound like we might want to aim for good post-human/transhuman scenarios (if aiming for the good versions specifically is relatively tractable), or for good scenarios in which something non-human is very much in control (like developing a friendly agential AI).

But maybe you don’t see possibility 2 as necessarily that concerning? E.g., maybe you think that something like mild or genuinely enlightened and benevolent authoritarianism accounts for a substantial part of the likelihood of authoritarianism?

(Also, I’m aware that, as you emphasise, the “4-in-5” claim shouldn’t be taken too seriously. I’m sort of using it as a springboard for thought—something like “If the rough worldview that tentatively generated that probability turned out to be totally correct, how concerned should I be and what futures should I try to bring about?”

Btw, I’ve now added your forecast to my “Database of existential risk estimates (or similar)”, in the tab for “Estimates of somewhat less extreme outcomes”.)

I’m not sure if that follows. I mainly think that the meaning of the question “Will the future be democratic?” becomes much less clear when applied to fully/radically post-human futures. But I’m not sure if I see a natural reason to think that the futures would be ‘politically better’ than futures that are more recognizably human. So, at least at the moment, I’m not inclined to treat this as a major reason to push for a more or less post-human future.

On the implications of my prediction for future people:

I definitely think of my prediction as, at least, bad news for future people. I’m a little unsure exactly how bad the news is, though.

Democratic governments are currently, on average, much better for the people who live under them. It’s not always possible to be totally sure of causation, but massacres, famines, serious suppressions of liberties, etc., have clearly been much more common under dictatorial governments than democratic governments. There are also pretty basic reasons to expect democracies to typically better for the people under them: there’s a stronger link between government decisions and people’s preferences. I expect this logic to hold, even if a lot of the specific ways in which dictatorships are on average worse than democracies (like higher famine risk) become less relevant in the future.

At the same time, I’m not sure we should be imagining a dystopia. Most people alive today live under dictatorial governments, and, for most of these people, daily life doesn’t feel like a boot on the face. The average person in Hanoi, for example, doesn’t think of themselves as living in the midst of catastrophe. Growing prosperity and some forms of technological progress are also reasons to expect quality of life to go up over time, even if the political situation deteriorates.

So I just want to clarify that, even though I’m predicting a counterfactually worse outcome, I’m not necessarily predicting a dystopia for most people, or a scenario in which most people’s lives are net negative. A dystopian future is conceivable, but doesn’t necessarily follow from a lack of democracy.

On the implications of my prediction for “value lock-in,” more broadly:

I think the main benefit of democracy, in this case, is that we should probably expect a wider range of values to be taken into account when important decisions with long-lasting consequences are made. Inclusiveness and pluralism of course doesn’t always imply morally better outcomes. But moral uncertainty considerations probably push in the direction of greater inclusivity/pluralism being good, in expectation. From some perspectives, it’s also inherently morally valuable for important decisions to be made in inclusive/pluralistic ways. Finally, I expect the average dictator to have worse values than the average non-dictator.

I actually haven’t thought very hard about the implications of dictatorship and democracy for value lock-in, though. I think I also probably have a bit of a reflexive bias toward democracy here.

It sounds like you mainly have in mind something akin to preference aggregation. It seems to me that a similarly important benefit might be that democracies are likely more conducive to a free exchange of ideas/perspectives and to people converging on more accurate ideas/perspectives over time. (I have in mind something like the marketplace of ideas concept. I should note that I’m very unsure how strong those effects are, and how contingent they are on various features of the present world which we should expect to change in future.)

Did you mean for your comment to imply that idea as well? In any case, do you broadly agree with that idea?

Interesting, thanks! I think those points broadly make sense to me.

I think this is a good point, but I also think that:

The use of the term “dystopia” without clarification is probably not ideal

A future that’s basically like the current-day Hanoi everywhere forever is very plausibly an existential catastrophe (given Bostrom/Ord’s definitions and some plausible moral and empirical views)

(This is a very different claim from “Hanoi is supremely awful by present-day standards”, or even “I’d hate to live in Hanoi myself”)

In my previous comment, I intended for things like “current-day Hanoi everywhere forever” to be potentially included as among the failure modes I’m concerned about

To expand on those claims a bit:

When I use the term “dystopia”, I tend to essentially have in mind what Ord (2020) calls “unrecoverable dystopia”, which is one of his three types of existential catastrophe, along with extinction and unrecoverable dystopia. And he defines an existential catastrophe in turn as “the destruction of humanity’s longterm potential.” So I think the simplest description of what I mean by the term “unrecoverable dystopia” would be “a scenario in which civilization will continue to exist, but it is now guaranteed that the vast majority of the value that previously was attainable will never be attained”.[1]

(See also Venn diagrams of existential, global, and suffering catastrophes and Clarifying existential risks and existential catastrophes.)

So this wouldn’t require that the average sentient being has a net-negative life, as long as it’s possible that something far better could’ve happened but now is guaranteed to not happen. And it more clearly wouldn’t require that the average person has a net-negative life, nor that the average person perceives themselves to be in a “catastrophe” or “dystopia”.

Obviously, a world in which the average person or sentient being has a net-negative life would be even worse than a world that’s an “unrecoverable dystopia” simply due to “unfulfilled potential”, and so I think your clarification of what you’re saying is useful. But I already wasn’t necessarily thinking of a world with average net-negative lives (though I failed to clarify this).

[1] That said, Ord’s own description of what he means by “unrecoverable dystopia” seems misleading: he describes it as a type of existential catastrophe in which “civilization [is] intact, but locked into a terrible form, with little or no value”. I assume he means “terrible” and “little to know” when compared against an incredibly excellent future that he considers attainable. But it’d be very easy for someone to interpret his description as meaning the term is only applying to futures that are very net-negative.

I also think “dystopia” might not be an ideal term for what Ord and I want to be referring to, both because it invites confusion and might sound silly/sci-fi/weird.

This section doesn’t explain why automation will lead to a dictatorship, as opposed to something like an aristocracy or plutocracy, i.e., rule by a relatively large elite who own or control the automation. My LessWrong / Alignment Forum post AGI will drastically increase economies of scale can perhaps help to close this gap.

Judging by some of your footnotes, it seems that you’re mainly motivated by the question of whether there will be a Long Reflection that’s democratic or highly inclusive. I have recently become more pessimistic about such a Long Reflection myself, and would be interested if you have any thoughts on my concerns.

I think this argument is harmed by imposing a democracy or dictatorship framework; while I understand the need to simplify, this obscures details that would be useful to us.

Dictatorship is pretty firmly anchored in fascism and communism, which depended strongly on effective centralized bureaucracies and rule of law to work. The kinds of things which could be accomplished by dictators of this era was simply beyond the scope or precision of all but a few rulers in the premodern eras.

I think following the thread of economic arguments is very valuable. In the industrialization section you mention the divisibility and immobility of land as being a factor; similar to this line of thinking is the condition of pastoral populations on the Steppe or Great Plains. The capital in these societies was all wrapped up in animals which were fully mobile, which makes oppressing people very difficult. Among the Mongols the position of khan was decided by election at the kurultai, where people voted with their feet in a literal fashion: in regional elections people joined the camp of the person they supported (along with their animals).

But economic arguments aren’t where the value lies per se. There was a type of kingship practiced in certain tribes in Africa which we would interpret as having a fundamentally religious function. Though the obvious trappings of power were there, like wealth and wives and servants, the actual function of the king was to be sacrificed in the event anything really bad happened. By this I mean droughts, famines, pestilence, and other natural occurrences over which the king had no hope of control. Now this method was never widespread, but I think if we sum up all the similarly-different-from-dictatorship traditional systems we will capture a huge chunk of the historical record.

To get around this problem, I think in the future the focus would benefit from shifting a level down, to mechanisms of power and the conditions needed to exercise them. Economics is pretty good at pointing this out, but as mentioned in the post we shouldn’t neglect the cultural elements like tradition or religious practices.

Thanks, I enjoyed reading this.

Here are a few thoughts; they aren’t meant as critiques of things you say, but simple thoughts triggered by, building on or attempting to complement your analysis.

What plausible outside views are there? How much to rely on which?

Here is another possible outside view one could take. Under this view, the question of how societies govern themselves is subject to evolutionary dynamics. (You allude to this a bit in one of your footnotes, when talking about economic determinism.) Different societies adopt different approaches, and societies with better approaches are more successful and become more dominant. Less successful societies either cease to exist or adopt the better approaches by imitation. Based on this view, we can identify “evolutionary pressures” and know some things about where these pressures are likely to steer us in the future. (Obviously we still don’t know exactly where this development leads us, but the space of possible developments is in fact constrained by these co-evolutionary dynamics.)

What specifically might “fitness” look like here? Taking a perspective as roughly outlined in this paper, we could posit that in order for a species to grow ever larger in scale, it requires (what in the paper is called) information processing capacity. Democracy (or government/the policy making apparatus at large) can be viewed as essentially such an information processing technology, and thus adaptive/fitness enhancing. Given the size and complexity of present day societies, it does look like the largely top-down information processing technology of an authoritative regime would less adaptive.

One can argue that democracy is a “successful adaptation” and thus is likely stick around. Maybe this is true, but I think this argument is way harder to make than what I’ve offered above, and I’m not actually sure it stands. Reasons why this isn’t straightforward include that the evolutionary dynamics described above are not very pure (compared to “proper” Darwinian natural selection), and that the environmental conditions within which the process unfolds are changing drastically, which could for example mean that adaptations that were fitness enhancing in the past won’t be in the future.

The reason I do bring this argument up however is that I think it suggests that we shouldn’t pay much attention to the “regression to the means” type arguments. I agree this is a prior to use, but I think we know enough about the territory that we shouldn’t rely much on it.

(I don’t necessarily think you do (though I don’t know). This is to say, I can see how you might get to the 4 in 5 prediction without invoking a “regression to the means” type argument, but by solely looking at the arguments you have for example layed out in your section on automation.)

Moral progress

I largely agree with your assessment that and how automation puts a lot of pressure on the fate of democracy (although, as you acknowledge, there are ways automation could strengthen democracy, and the way this will cash out sure seems liek it’s subject to strong path dependency.)

When we compare pre-industrial times to post-industrial times, it is not only our economy and our arsenal of technologies that is different. Within these ~200-300 years, humanity has also undergone meaningful intellectual and moral progress. This includes things like coming to think that women and people of colour are full members of society, or spelling out values such as freedom, self-realization, etc. If automatisation will lead to power being concentrated in the hands of a small elite, this also means that the beliefs and values of this elite become more important.

Of course, if their moral ideals are in stark contrast with others, e.g. economic interests, we should expect they will just throw most of these ideals over board or engage in elaborate rationalizations to present they are still holding them up high. But if the conflict of interst remains relatively weak, I do think this migth be a factor that palys a role.

If democracy retreats, what will it be replaced by?

A lot of the time, people assume a natural dichotomy between democracy and authoritative regimes. While this is certainly a useful shorthand when looking at history, I think it is likely to be misleading when thinking about the future.

This “false dichotomy” between democracy and authoritative regimes often contrasts “my values and needs are adequately taken into account” (<> democracy) with “my values and needs basically don’t matter” (<>authoritative regimes). By putting these things into the same bucket, we might overlook ways in which these connections might come apart.

For example, I might not inherently care about whether I will be able to directly or indirectly choose my political leader, but I definitely care about how well my values and needs will be taken into account in this process that steers my society into alternative futures.

Relatedly, discussions about democracy are often just as much about “democratic values″ (e.g. liberty, equality, justice) as they are about “the process of choosing our own leaders”.

I’d be curious whether your prediction about whether democracy will still be around in one thousand years largely overlaps with your prediction about, say, “will an average person in a thousand years from now feel like their values and needs are adequately taken into account by whoever or whatever is making decisions about how their society is being governed?”. (Of course, other operationalizations might be interesting, too).

The latter is much harder to predict, and democracy as you defined it might be the correct way of approaching the latter question. That said, understanding more about how lieky they are to come apart, and if so how seems potentially interesting.

This reminds me of an interesting Eric Drexler talk on “paretotopian goal alignment”, which may be of interest to readers of this post.

Running with the valley metaphor, perhaps the 1990s were when we reached the most verdant floor of the valley. It remains unclear if we’re still there or have started to climb out and away from it, assuming the model to be correct.

I would actually bet on average democracy continuing to increase over the next few decades.* Over this timespan, I’m still pretty inclined to extrapolate the rising trend forward, rather than updating very much on the past decade or so of possible backsliding. It also seems relevant that many relatively poorer and less democratic countries are continuing to develop, supposing that development actually is an important factor in democratization.

I also don’t think there are any signs that automation is already playing a major role in democratic backsliding. (I think much more automation is probably necessary). So, unless there’s really rapid AI progress, I don’t expect the specific causal mechanism I’m nervous about to kick in for a while.

*Off the top of my head, conditional on the Polity project continuing to exist, I might say there’s something like a 70% chance that the average country’s Polity score is higher in 2050 than it is today.

I really like your point about automation changing the balance of power between elites and workers, potentially eliminating the threat of strike or revolt.

I think this argument is interesting. Maybe this is my neoclassical-econ bias speaking, but I’m more skeptical of automation displacing human labor (as I’ve said in this shortform). It’s not clear to me that AI firms will have economic incentives to produce general AIs as opposed to more narrow AIs, and I think mass technological unemployment is less likely without general AI.

Thanks for the comment!

I think endnotes 12 and 13, within my cave of endnotes, may partly address this concern.

I don’t think the prediction that the labor share will fall in the future depends on (a) the assumption that the amount of work to be done in the economy is constant, (b) the assumption that automation is currently reducing the demand for labor, or (c) the assumption that individual AI systems will tend to have highly general capabilities. I do agree that the first two assumptions are wrong. I also think the third assumption is very plausibly wrong, in line with some of the analysis in Reframing Superintelligence.

I think the prediction only depends on the assumption that, in the future, it will become unnecessary (and comparatively more expensive) to hire humans workers to produce goods and services. I find this assumption really plausible. The human brain is ultimately just a physical thing, so there’s no fundamental physical reason why (at least in aggregate) human-made machines couldn’t perform all of the same tasks that the brain is capable of.[1] I also think it’s likely that engineers will eventually be able to make these kinds of machines; seemingly, the vast majority of AI researchers expect this to happen eventually. There are also, I think, very strong economic incentives to make and use these machines. If a business or state can produce goods and services more cheaply or effectively, by escaping the need to hire human workers, then it will typically want to do this. Any group that continues to pay for a lot of unnecessary human workers will be at a disadvantage.

This prediction is consistent with the observation that, historically, automation has tended to increase overall demand for labor. When one domain becomes highly automated, this tends to increase the demand for labor in complementary domains (inc. domains that did not previously exist) which are not highly automated. My understanding is that this dynamic explains why automation has mainly been driving wages up for the past couple hundred years. But the dynamic seems to break down once there are no longer any complementary automation-resistant domains.

For example: Suppose we live in a cheese-and-bread economy. People like eating cheese sandwiches, but don’t like eating cheese on its own. It then seems like completely automating cheese production (using machines that are more efficient than humans) will tend to increase demand for workers to staff bread factories. Automating both cheese and bread production, though, seems like it would pretty much eliminate the demand for labor. If either factory has an extra ten thousand dollars to spare, then (seemingly) they have no incentive to use it to pay a human worker a living wage, rather than spending it on capital that will increase output by a larger amount.[2]